I. Introduction

The consumer welfare standard has guided antitrust agencies and courts for the past fifty years.[1] Prior to its arrival and the concurrent advent of the modern approach to antitrust, cases depended on a host of factors including categorical structural presumptions,[2] promotion of small businesses,[3] and protection of rival competitors.[4] The arrival of the standard, however, clarified how to consider the impact of business conduct.[5] Specifically, many antitrust decisions boiled down to a simple question: what happens to the welfare of consumers with and without the conduct at issue?[6] While the beneficial features and associated defense of the standard have been amply and ably detailed,[7] one potential benefit has been largely ignored. The consumer welfare standard’s simple and intuitive approach to address complex business practices not only streamlines the objective of antitrust laws for decision-makers but also for the public at large. On this point, several decades ago, Donald Turner, former head of the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Antitrust Division under President Johnson, succinctly explained that incorporating noneconomic, populist goals “would broaden antitrust’s proscriptions to cover business conduct that has no significant anticompetitive effects, would increase vagueness in the law, and would discourage conduct that promotes efficiencies not easily recognized or proved.”[8] More recently, Christine Wilson, while a commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), along with her fellow authors, argued that adopting a standard with multiple objectives would make it “likely that consumers would question antitrust enforcement that chooses to eliminate low prices, whether in the interest of protecting small businesses that wish to charge consumers higher prices or to protect jobs at firms that are acknowledged to be inefficient.”[9]

In short, under the current antitrust standard, a plaintiff’s victory signals to the public a successful demonstration of harm to consumers.[10] Consequently, the ruling and remedy—including breaking up a company—has a foundational justification, regardless of any disagreements on the appropriate nature of a remedy or its severity.[11] On the other hand, a defendant’s victory signals to the public that the allegations of harm were misplaced, and careful consideration of the conduct revealed consumers were not or would not be harmed and, more likely, benefited or will benefit from the conduct. Thus, a finding of no liability vindicates the defendant’s business practice on grounds that do not require a deep knowledge of the law, public policy, or economics to understand.

A reform movement is underway, however. While the groundwork has been laid for over a decade,[12] the calls for reform have accelerated in the past several years. For instance, the current White House administration has made clear its opposition to modern antitrust law, which incorporates economics and the consumer welfare standard.[13] Relatedly, the current heads of the U.S. antitrust agencies have not hidden their dislike of the consumer welfare standard—finding it too limiting for plaintiffs and too generous to defendants.[14] For instance, the assistant attorney general of the antitrust division at the DOJ has advanced a nebulous “protect competition” standard that appears to be a rebranding of a prior era’s effort to fold in the welfare of competitors—including small businesses, workers, and others—along with consumers.[15] In July 2023, this change in policy direction culminated in the release of the Draft Merger Guidelines,[16] which reflect the view that the burden on plaintiffs has been too high—thus, advocating a return to structural presumptions[17]—and that procompetitive claims should generally be dismissed or, at most, considered with heavy skepticism.[18] In the world of academia, the reform proposals are similarly aggressive to address a host of allegations against the consumer welfare standard.[19] Broadly, the “neo-Brandeisian” reform proposals are attempts to either (1) severely tilt the consumer welfare standard in favor of plaintiffs; (2) complicate the standard with additional considerations; or (3) replace the standard altogether.[20] Regardless of the specific reform proposal, the likely outcome will be the same: the expansion of antitrust enforcement objectives will muddy the meaning of liability.

This Article examines the consequences of using broader standards than the consumer welfare standard from the perspective of the general public, including consumers and investors. Specifically, if antitrust becomes a patchwork of varying objectives along with legislative measures that interface with the antitrust laws,[21] then the information value of antitrust decisions may fall. A plaintiff’s victory could stem from a host of reasons as the relationship between the condemned business conduct and consumer welfare becomes significantly noisier—if the relationship does not break altogether.[22] For instance, one legislative proposal would deem acquisitions by certain companies—regardless of their actual market power in a given market—presumptively illegal,[23] even if the same presumption would not hinder the same acquisition by another company with actual market power.[24] In this environment, the public will find it increasingly difficult to determine whether consumers are better or worse off. Or, more concerningly, consumers will realize they are worse off while other interest groups, such as other suppliers in the market, are better off.[25]

Why is this relevant? The public’s interpretation of legal decisions can have real economic consequences. In other contexts, such as criminal law, a “guilty” verdict for corporations can result in a serious reduction in their value.[26] In essence, the stigma of a criminal record further raises the cost of violating the law.[27] Similarly, if a firm is found liable in an antitrust case, the reputational impact on the firm can cause material swings in valuation.[28] However, if the business conduct’s legality is assessed using a host of factors, such as the impact on rivals, political groups, employment levels, the environment, diversity, and income distribution, then what precisely gives rise to the firm’s liability?[29] Under these circumstances, a plausible conjecture is that a win for a plaintiff may have almost no reputational effect, or an effect that is materially less significant than a verdict under the consumer welfare standard. Specifically, some existing empirical studies suggest that firms suffer large reputational sanctions due to findings that they have harmed consumers but not due to similar conduct harming third parties.[30]

The central contribution of this Article is to develop a model to consider the consequences of replacing the consumer welfare standard on the level of firms’ compliance. To that end, Part II details the information value of the consumer welfare standard and contrasts the standard with various reform proposals. Having a legal standard serves two main roles: to determine liability and to deter specific conduct.[31] If a firm is considering engaging in behavior that could ultimately harm consumers, it will consider the expected cost of such behavior. The expected cost is a function of the expected sanction, which incorporates both the likelihood of detection and the penalty, but also the expected reputational damage.[32] If a reformed standard defines “anticompetitive” as broader than conduct found to harm consumers, then the firm’s ex ante calculation may also change. Thus, Part III illustrates this potential change by modeling the reputational impact of antitrust verdicts under different legal standards. Part IV then discusses the implications of the results. Ultimately, this Article demonstrates that reforming antitrust away from the consumer welfare standard may not only cause legal uncertainty but may also result in less deterrence. In other words, the reformation movement may not even achieve its core objective: to reduce the frequency of certain business practices. In fact, as another potential application of the law of unintended consequences,[33] a reform could produce more of the targeted behavior.

II. Consumer Welfare Standard v. Alternative Standards

A. The Consumer Welfare Standard

The well-documented evolution of antitrust law describes the adoption of the consumer welfare standard.[34] Over time, courts, agencies, practitioners, and scholars have widely accepted this standard because it brings “coherence and credibility” to antitrust law.[35] To that end, several key virtues of the standard account for its broad acceptance. First, the standard is simple to interpret due to its singular focus on the welfare of consumers. Business practices such as resale price maintenance, exclusive dealing, and mergers are multifaceted and impact various parties, including the firm itself, labor, rivals, supply chain partners, and consumers.[36] Without a “lodestar” focused on competition’s impact on consumers,[37] the enforcement of antitrust laws likely becomes a game of uncertainty with potentially capricious verdicts. Second, the standard offers a conceptually straightforward guide to agencies and courts as to what evidence is relevant to examine; namely, relevant evidence reveals how the business practice impacts various market outcomes, including price, quantity, quality, and innovation—from the perspective of consumers, not competitors.[38] Relatedly, the standard deters arbitrary or politically motivated enforcement activities[39] as these objectives are inconsistent and separate from consumer welfare. Together, these virtues create discipline in the enforcement of antitrust laws and offer transparency to court decisions.

Importantly, the consumer welfare standard relates to the efficiency of markets to the extent those efficiency gains are passed on to consumers.[40] While the focus on efficiency and consumer welfare are normative concepts or value judgments, economists widely use these value judgments as measures of a market’s performance.[41] Further, efficiency does not explicitly incorporate wealth distribution;[42] therefore, the consumer welfare standard does not sacrifice the size of the economic “pie” in an effort to give one group more of the pie. Thus, the consumer welfare standard does not depend on equity—as other value judgments might; although, importantly, improvements in efficiency are not necessarily contrary to improvements in equity.[43]

Regardless of the debates about the accuracy of antitrust decisions and the frequency and magnitudes of false positives and false negatives,[44] error costs are not unique to the consumer welfare standard.[45] Error costs are part of all legal regimes due to the inherent uncertainty of making decisions without full information.[46] While courts may ultimately get a decision wrong,[47] the consumer welfare standard provides an objective basis for assessing whether decisions were correct and—in the event of a wrong decision—for revising approaches and developing new tools.[48] Consequently, judgments under the consumer welfare standard send a clear message to all interested parties, including other market actors, agencies, courts, investors, and consumers—both actual and potential.[49]

Notably, antitrust law has not always had such a clear approach to enforcement. Prior eras saw courts interpreting the Sherman and Clayton Acts unevenly at best[50] and, at times, condemning low prices,[51] protecting inefficient competitors,[52] and favoring the politically connected.[53] Yet, the intellectual revolution of the 1970s and 1980s that brought about the modern era of antitrust and the consumer welfare standard is now facing a new revolution to roll back those reforms.

B. Alternative Proposed Standards

Proposals to reform antitrust can broadly be organized into three categories. First, there are attempts to further tilt the current consumer welfare standard in favor of plaintiffs. Second, there are attempts to supplement the consumer welfare standard with additional objectives and considerations. Third, there are attempts to replace the standard altogether. This Section details each of these categories with a particular focus on the latter two categories because they are the most likely to dilute the reputational impact from liability.

1. Tilting the Consumer Welfare Standard in Favor of Plaintiffs

The consumer welfare standard assesses most conduct using the rule of reason framework, which was established in the early 20th century.[54] In fact, the framework, which involves a three-step process, may only make sense under a consumer welfare standard.[55] Initially, the prima facie burden is on the plaintiffs to demonstrate anticompetitive harm. Afterward, the defendants have an opportunity to offer procompetitive justifications. Finally, the plaintiffs can argue that there are less restrictive alternatives to achieve efficiency gains. Within this structure, there are burdens of production on both parties;[56] however, the ultimate burden of persuasion always remains with the plaintiff.[57]

Some argue that using the current rule of reason framework to operationalize the consumer welfare standard has led to underenforcement.[58] If so, then a proposed solution to tilt the consumer welfare standard in favor of plaintiffs would lower the burden of production on plaintiffs or increase the burden on defendants.[59] For instance, the Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Act, sponsored by Senator Amy Klobuchar, would implement a lower standard for plaintiffs to prove anticompetitive harm from mergers by moving away from the current “substantially” lessening competition standard to “an appreciable risk of materially” lessening competition standard.[60] Moreover, the bill would increase the burden on defendants by considering large mergers and mergers that substantially increase concentration to be presumptively unlawful with the burden on the merging parties to prove the merger is not unlawful.[61] Even within the antitrust agencies, policy reforms have been advanced, such as the recent Draft Merger Guidelines, which substantially lessen the burden of production on plaintiffs—namely, through a push to broaden and strengthen structural presumptions for both horizontal and vertical mergers.[62] Additionally, according to the Draft Merger Guidelines, mergers that tend to create a monopsony in a labor market would also be impermissible[63]—irrespective of the impact on consumers in the final goods market.[64]

A more targeted proposal is the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act, sponsored by Representative Hakeem Jeffries.[65] This bill prohibits “covered platform[s]” (essentially, technology companies with more than fifty million users and $600 billion in annual sales or market capitalization) from making acquisitions unless there is no competitive overlap between the two companies.[66] Although, even if there is no overlap, acquisition challenges can still proceed based on theories of “nascent or potential competition.”[67] Thus, for mergers of “covered platform[s],” the bill’s standard favors plaintiffs.[68]

Beyond mergers, the American Innovation and Choice Online Act, sponsored by Representative David Cicilline, also targets “covered platforms” and raises the burden on such defendants.[69] The bill would ban or limit business conduct such as “self-preferencing” one’s own products and would require platforms to allow for interoperability and certain kinds of data sharing.[70] Specifically, regarding self-preferencing, the bill expressly declares conduct that “advantages the covered platform operator’s own products, services, or lines of business over those of another business user” as unlawful.[71] While the bill permits an affirmative defense, the platform must show “clear and convincing” evidence—a more onerous standard than a preponderance of the evidence—that the conduct does not harm the competitive process or is necessary to protect user privacy.[72]

Outside the legislature, the U.S. antitrust agencies propose altering the rule of reason framework to further favor plaintiffs.[73] Under the rule of reason, defendants can rebut allegations of anticompetitive harm with verifiable and cognizable efficiencies, that is, procompetitive justifications for the conduct. Removing this ability would hamper a defendant’s attempt to justify its conduct to the extent that it actually benefits consumers, such as lowering prices, increasing output, or improving quality. Thus, perhaps unsurprisingly, both heads of the U.S. antitrust agencies are seeking to eliminate or severely limit this “rebuttal step.”[74] Relatedly, some academics, practitioners, and agency officials have proposed further restricting a defendant’s ability to use “out-of-market” efficiencies to justify business conduct.[75] Out-of-market efficiencies are procompetitive business justifications that occur outside of the strict confines of the “relevant market”[76] where the alleged anticompetitive harm occurs.[77] While the assessment of horizontal mergers generally excludes out-of-market efficiencies,[78] they are relevant when assessing vertical mergers and unilateral conduct assessed under the Sherman Act—although there is some degree of uncertainty for this latter application.[79] Given the uneven treatment of out-of-market efficiencies, some proposals call on Congress to unilaterally prohibit all consideration of out-of-market efficiencies—particularly in cases focused on balancing effects across groups in multi-sided platforms.[80] In sum, whether for “in-market” or “out-of-market” efficiencies, the current reform movement—lead by the heads of the U.S. antitrust agencies, academics, and practitioners—is clearly looking to impair a defendant’s ability to offer procompetitive justifications for business conduct.

Overall, the Stigler report offers a summary of the idea in support of calibrating the burdens in favor of plaintiffs:

Burdens of proof might be switched by adopting rules that will presume anticompetitive harm on the basis of preliminary showings by antitrust plaintiffs and shift a burden of exculpation to the defendant or by ensuring that plaintiffs are not required to prove matters to which the defendants have greater knowledge and better access to relevant information.[81]

More specifically, “[m]ergers between dominant firms and substantial competitors or uniquely likely future competitors should be presumed to be unlawful”;[82] “[c]ourts should not presume efficiencies from vertical transactions”;[83] and “[c]ourts should be more willing to permit plaintiffs to prove harm to competition by circumstantial evidence.”[84] Thus, while the described proposals are ostensibly still within the consumer welfare standard, the result would hide the new, favorable standard for plaintiffs behind a cardboard cutout of the current framework and standard.

2. Supplementing the Consumer Welfare Standard

The second category of proposals also aims to generally preserve the consumer welfare standard but incorporates additional objectives. While the specifics of each proposal vary, they share the common feature of complicating the administration of the antitrust laws. One prominent example is the additional consideration of income inequality. For instance, Baker and Salop propose to recognize the economic and social concern with inequality as an antitrust goal, along with consumer welfare and efficiency. Alternatively (or in addition), Congress could add an explicit ‘public interest’ goal to the Sherman and Clayton Acts that would instruct the courts to interpret them as allowing the use of the antitrust laws to address distributional effects.[85]

The advocates of this standard acknowledge that implementing distribution concerns would further complicate antitrust decision-making.[86] Additionally, beyond just gathering and weighing more evidence, this standard would require making value judgments in terms of the welfare tradeoffs between various households based on their income levels,[87] as well as shareholders.[88] In the end, given the nebulous and subjective views of inequality, interpreting antitrust decisions under this expanded consumer welfare standard would get increasingly noisy.

Another proposal would, in addition to considering the welfare of consumers, consider the protection of smaller competitors and a notion of incorporating “fairness.”[89] Specifically, Stucke has proposed combining “several popular competition goals, ensuring: (1) an effective, competitive process by enhancing efficiency, while promoting economic freedom; (2) a level playing field for small and mid-sized enterprises; and (3) fairness.”[90] This idea of a blended approach to antitrust enforcement relies on incorporating the welfare of rival suppliers into the assessment of the legality of specific business conduct. Notably, this proposal adds inherently subjective concepts such as “economic freedom” and “fairness.”[91]

Likewise, there are proposals to add precise considerations to the standard. For example, numerous proposals want to incorporate labor market deliberations.[92] The basic idea is that worker welfare should matter just as much as consumer welfare.[93] Other proposals include the objective of combating fake news[94] and political corruption.[95]

In sum, these proposals would materially complicate antitrust adjudication, including the need to assess completely different types of evidence.[96] Importantly, these “add-on” proposals, if implemented, could cloud the meaning of finding liability. Specifically, many of these proposals would involve comparing the welfare of completely different groups, including rivals, consumers, and labor.[97] Holding aside the administrative burden, a finding of liability could result from harming some rivals, even though most consumers benefited. If so, what should consumers and investors do with this information, in terms of their willingness to purchase from the firm or invest in it?

3. Replacing the Consumer Welfare Standard

The final category of proposals is attempting to replace the consumer welfare standard with an entirely new standard. This categorization is not entirely independent of the prior Section’s description of various proposals to add on considerations to the current focus on consumer welfare. For instance, the proposed “public interest” standard effectively combines the consumer welfare standard and other “public interest” objectives into one new standard.[98] Other examples, further described below, are proposals to adopt a “protection of competition” standard[99] and a “consumer choice” standard.[100]

Proposals involving a “public interest” standard generally attempt to roll up several disparate, often vague, objectives into one broad, encompassing standard.[101] There is some precedent for this with the Communications Act of 1934, requiring that broadcast licensees (that is, over-the-air television and radio owners) conform their operations to “public interest, convenience and necessity.”[102] Not surprisingly, the enforcement goals of such a flexible standard involving the “public interest” have not been clear under the Communications Act.[103] As it applies to antitrust, using a public interest standard raises the same issues detailed in the prior Section when attempting to consider and balance multiple objectives.[104] Ultimately, the primary focus of this Article is on the inherent vagueness of “fairness” and “public interest,” which will conceivably muddy the message that a finding of liability sends.

Another proposal is a “protection of competition” standard.[105] The idea is to focus more on the process of competition rather than measurements of outcomes.[106] While perhaps having an intuitive appeal, advocates acknowledge the likely difficulty in implementing the standard.[107] Indicative of this, one of the suggested questions to ask in implementing the standard seemingly would generate more uncertainty than guidance: “Does the complained-of conduct or merger tend to implicate important noneconomic values, particularly political values?”[108] Suppose the answer is “yes” to this question. It is not hard to imagine quite broad interpretations of “political values.” Even if we could reasonably categorize political values, how do they relate to the protection of competition? Notably, the idea of “protec[ting] competition” is akin to protecting the “competitive process.”[109] This latter phrasing, however, introduces some confusion because the phrase “competitive process” is already used in antitrust. Specifically, economists such as Greg Werden widely use the phrase.[110] Additionally, courts use the phrase “must harm the competitive process and thereby harm consumers” to indicate anticompetitive conduct, but “harm to one or more competitors will not suffice.”[111] Importantly, the common use of the phrase “competitive process” is arguably to put a finer point on the meaning of the consumer welfare standard, rather than representing a deviation from the standard.[112] In contrast, the recent use of the phrase by some reformers is largely a cosmetic rebranding to broaden the notion of anticompetitive harm—including the incorporation of rivals’ welfare—whether this is acknowledged explicitly or not.[113] While harm to rivals is part of almost every theory of harm, even under the consumer welfare standard, such as foreclosure or predatory pricing,[114] the ultimate arbiter of liability is the impact on consumers instead of harm to rivals in and of itself. Thus, the effect of the use of a “protecting competition” standard is largely indistinguishable from use of a public interest standard.

Other proposals advance that antitrust laws must promote “economic liberty.”[115] The phrase originated in the 1958 Supreme Court case, Northern Pacific Railway Company v. United States.[116] Similar to other proposals, the “economic liberty” proposal aims to broaden the reach of antitrust beyond consumers to include the welfare of rivals—especially small businesses—and to consider the impact of market conduct on the political system.[117] A variation of the economic liberty argument is a “citizen interest” standard.[118] This variation purports that “[a]ntitrust should protect consumers from anticompetitive overcharges and small producers from anticompetitive underpayments, preserve open markets, and disperse economic and political power.”[119] Further, the “citizen interest” standard, while not explicitly adopting income redistribution as a goal, seeks to “mitigate inequality” through its application.[120]

Finally, Averitt and Lande’s “consumer choice” standard is a somewhat less disruptive proposal.[121] Unlike most of the previously discussed proposals, this standard is less about adding completely new objectives to antitrust enforcement and more about adding a consideration of the number of choices that consumers have. The core argument is that the consumer welfare standard does not handle nonprice effects well;[122] therefore, the proposed “consumer choice” standard augments the current standard with an inquiry into “whether a particular business practice has resulted in some unreasonable and significant limitation on consumer choice.”[123] The problem with this proposed standard is that having more products in a market does not map in a reliable way with consumer welfare.[124]

Ultimately, across all the reviewed proposals, whether building on the consumer welfare standard or replacing it altogether, the objectives are surprisingly similar. The idea is to make antitrust a “big tent” of liability that captures business conduct beyond its impact on consumers. The impact can include the welfare of rivals—particularly the welfare of smaller ones; workers and employment levels; political groups; and the households at different levels of income and wealth.

Interestingly, attempts to broaden the interpretation of the antitrust laws have occasionally appeared in prior agency cases—even during the consumer welfare era. In these instances, courts have seen their role as restraining agency “abuse of power” against “legitimate practices.”[125] Ultimately, historically and economically, courts have addressed shifts away from clear guidance and recognized the importance of coherence in the application of antitrust laws.[126]

The question this Article raises is whether this shift away from the consumer welfare standard reduces the information value of findings of liability. If so, this can have negative implications regarding reputational incentives. The next Part formalizes these dynamics through an economic model of information and reputation.

III. Modeling Reputational Effects from Antitrust Verdicts

Undoubtedly, proposals to broaden or move entirely away from the consumer welfare standard will fundamentally change the adjudication of antitrust law. Perhaps the implementation of a new standard will feature strong presumptions of harm, which could lower administrative costs but at the expense of imposing burdensome error costs on markets.[127] Perhaps the implementation will weigh the welfare of multiple groups to determine liability. Either way, under a new standard, a finding of liability will mean something profoundly different than it does today. Under the current consumer welfare standard, a finding of liability sends a clear signal to third parties: the conduct has harmed or will harm consumers.

In contrast, a finding of liability under a public interest standard could result from a host of reasons, including alleged harm to consumers, rivals, labor, lower-income households, or political groups.[128] Consequently, even if we assume agencies and courts can properly weigh these various considerations, an important question is how the verdict will impact the market—namely, the information value to consumers and investors. If a firm is found liable for violating antitrust laws under these broader and vaguer standards, then will the public substantially “punish” the firm further with economic sanctions channeled through reputational losses—that is, withholding future business or withdrawing investment funds? If so, what is the extent of this punishment compared to those that would be obtained through a finding of liability under the consumer welfare standard? To that end, this Part formally models the impact of altering antitrust standards on the reputational consequences associated with a finding of antitrust liability.

The main insights that emerge from this modeling exercise are intuitive and can be summarized as follows: A finding of liability signals that the firm is a “low” type, on average, relative to a firm that is not found liable.[129] Here, type refers to underlying characteristics of the firm, which may include their organizational skills or the relative value they place on producing reliable products relative to cost savings. Because consumers place greater value on the characteristics of “high” types, they are willing to pay more for their products relative to those sold by low types. This manifests itself in the form of a downward demand shift for the products of the penalized firm. Relatedly, investors can take the wrongdoing of the firm as a signal that the firm has some hidden bad characteristic that may cause organizational problems or reduced demand for the firm’s product in the future. As a result, stockholders of firms may wish to sell their stocks at current prices, and potential future investors may decide not to invest in the firm. All these acts reduce the firm’s value, which we collectively call reputational sanctions.

As noted in the empirical literature on reputational sanctions, stock prices of firms are more responsive to news regarding firm liability triggered by harm to consumers than to third parties.[130] We model this phenomenon by allowing different types of conduct to convey different types of information regarding firm type—where conduct harmful to consumers provides more relevant information. Therefore, broadening antitrust standards beyond consumer welfare dilutes the reputational sanctions associated with a finding of liability.[131]

The dilution of reputational sanctions implies that broader standards cause a reduction in the deterrence of consumer welfare reducing conduct, due to what we call the “stigma dilution effect.”[132] However, the same broadening of standards now enables the deterrence of acts that reform proponents argue are socially undesirable due to reasons other than harms to consumers.[133] Thus, the broadening of standards can be justified, despite the stigma dilution of consumer harming conduct, only if the broadened standard leads to a substantial reduction in the commission of the types of conduct that antitrust laws did not previously punish but would punish upon the broadening of antitrust standards. We show through illustrative simulations that the increase in consumer welfare-reducing conduct can more than offset the deterrence of the newly regulated conduct.[134]

In short, our analysis delivers two main points: First, our model suggests that broadening antitrust standards may, all else equal, increase the commission of consumer welfare-reducing acts; Second, it suggests that broader standards can, counter-intuitively, lead to an increase in the commission of conduct perceived to be harmful by those who advocate for broader standards. Next, we formalize these points through an economic model.

A. Model Setup

Let us consider a continuum of conduct, each of which can be committed by firms in a market. For instance, may be a classification of conduct based on the types and extent of harms they cause, for example, a small generates large harm to consumers, a large is completely benign, and an intermediate is not harmful to consumers but may cause harm to other parties. This type of classification can also be visualized through more discrete, familiar business practices: we can imagine that conduct captures the degree of collaboration among industry competitors (where means no collaboration and is naked price fixing) or the market share of the firm engaging in a particular practice, e.g., exclusive dealing or self-preferencing (where means de minimis market share).

The private benefit a firm obtains from committing conduct is and, therefore, each firm can be specified as a pair and we denote by the joint probability density function over firms. Similarly, we denote the associated cumulative distribution function as [135]

Only a subset of conduct is harmful to consumers, however, and we order them such that denotes a cut-off, where conduct is harmful to consumers if and only if For example, again, if conduct captures the degree of collaboration among industry competitors, then as collaborations move beyond the sharing of simple, best practices (e.g., close to 1) to naked price fixing (e.g., close to 0), then there is some threshold, where the collaboration becomes harmful to consumers. An antitrust agency (the agency) declares a subset of conduct illegal and imposes a sanction of whenever the agency detects the occurrence of such conduct (which happens with probability to deter such conduct.

If the agency uses the consumer welfare standard, then it only illegalizes acts Thus, the determination is that acts below the threshold of harm consumers while those above do not. On the other hand, if the agency uses a broader standard, then we order conduct such that there is a cut-off that captures more conduct than that is, such that all conduct is illegal.[136] In other words, there is a gap between the conduct that is permissible under the consumer welfare standard and a broader standard; conduct between and would become illegal under the broader standard—even though the conduct does not, on net, harm consumers. Importantly, in addition to the formal sanction a guilty verdict triggers reputational sanctions of [137] These reputational sanctions are determined endogenously, based on the equilibrium behavior of firms, which depends on the firms’ anticipated level of reputational sanctions.[138] Thus, we focus on Bayesian Equilibria as our solution concept and explain how the equilibrium reputational sanctions emerge.[139]

Given the standard adopted by the agency, a firm commits conduct if the firm’s benefit from the conduct, exceeds its anticipated net-expected cost associated with committing the conduct, where p is the probability of incurring the formal and reputational sanctions; is the formal sanction; and is the anticipated reputational sanction.[140] Therefore, the best response of firms, given their anticipated reputational sanctions, is to commit the conduct if it exceeds a threshold, given by:

br(ˆς)≡p(s+ˆς)<b

The above expression merely formalizes the idea that firms engage in a cost-benefit analysis depending on their specific “type” (that is, their pair of which determines whether the firm commits the conduct when On the other hand, all conduct where are legal and are, therefore, committed. We assume that the maximum benefit, from a given level of conduct is large enough to exceed the maximum expected sanction that can be obtained in equilibrium, such that for all anticipated reputational sanctions that are consistent with equilibrium outcomes.

On the other hand, third parties, such as potential customers, observe the firms found liable. Subsequently, these third parties make inferences regarding the types of firms that commit the conduct, i.e., the size of the benefits from violating the antitrust laws that a firm must possess to engage in wrongdoing. Formally, this corresponds to a cut-off benefit, such that only firms with commit conduct Based on this behavioral profile, third parties form beliefs about a firm’s type, which leads to the imposition of reputational sanctions on firms that are found liable. Thus, a Bayesian equilibrium exists when That is, third parties’ expectations are consistent with the behavior of firms who anticipate reputational sanctions imposed by third parties who possess those expectations. Next, this Article explains in further detail how third parties form beliefs and how these beliefs affect reputational sanctions.

B. Reputational Sanctions, Firm Incentives, and Equilibrium

Following the literature on laws and reputational incentives,[141] we assume that third parties make inferences about the quality of firms (denoted by based on whether the firms were found liable and that third parties adjust their interactions with firms based on these beliefs. Liability imperfectly signals information about quality because firm types (which are unobservable by third parties) are correlated with their quality where denotes the average quality of a type firm. Thus, a finding of liability (denoted as given a standard and cut-off is associated with an average quality of

E[q|l=1]=E[q|t≤ts and b>b∗]

This expression[142] reflects the fact that third parties can only infer that a firm found liable must be a type such that and

On the other hand, a firm that is not found liable (denoted may have committed nonregulated conduct (i.e., refrained from committing regulated conduct (i.e., and or committed an illegal act without being detected (i.e., and We denote the average quality of a firm not found liable as [143]

Below, Figure 1 depicts the inferences of third parties. The figure illustrates the only types of firms that are found liable (upper left box) in equilibrium, versus the firms that are not found liable in equilibrium. The difference in the average quality of these types, as we explain below, plays a crucial role in the determination of reputational considerations.

When third parties provide interaction values to firms that are proportional to their expectations about their quality,[144] it follows that the interaction value to firms from being found liable and not liable are given by and respectively, where k is a number indicating the proportion. Thus, given these interaction values, the overall expected value from committing an illegal act to a firm is:

b+pkE[q|l=1]+(1−p)kE[q|l=0]−ps

which incorporates the benefit from the act the expected value of the third-party interaction and the expected cost of a formal sanction In contrast, not committing an illegal act result in an expected value of:

kE[q|l=0]

The above equations imply that a firm with commits the act if:

p(s+kE[q|l=0]−kE[q|l=1])<b

Thus, the imposed reputational sanction can be expressed as:

¯ς(ts,b∗)≡kE[q|l=0]−kE[q|l=1]

Again, we note that, given any standard the equilibrium cut-off is given by:

b∗=br(¯ς(ts,b∗))

In many circumstances (including in the examples produced below), this equilibrium is unique, in which case we denote it as a function of the standard as and one can describe the equilibrium reputational sanction as a function only of the standard as:

ς(ts)=¯ς(ts,b∗(ts))

When the equilibrium is unique, one can describe comparative statics with respect to i.e., how changes in the antitrust standards affect outcomes, which we turn to next.

C. The Impact of Broadening Antitrust Standards

The impact of broadening the scope of antitrust enforcement on reputational incentives as well as on deterrence naturally depends on how much third parties can infer from various conduct. Cases where third parties care more, loosely speaking, about whether firms have committed acts that harm consumers correspond to cases where the commission of conduct with carries a large stigma. In our model, this corresponds to cases where is smaller for relative to In these circumstances, increasing beyond can reduce reputational incentives, i.e., by making the deviation between the average qualities of liable firms and non-liable firms smaller. We call this the “stigma dilution effect” of broadening standards because the broader standard reduces the expected reputational consequences, or stigma, associated with liability.

In these circumstances, a trade-off emerges between enhancing the scope of enforcement and reducing the compliance cut-off for regulated conduct. Below, Figure 2 depicts this trade-off by considering the impact of broadening the antitrust standard on the firm types that commit and do not commit the conduct.

Figure 2 illustrates the two countervailing effects associated with a broadening of standards. First, rectangle S represents the stigma dilution effect: broadening the standards, i.e., increasing to reduces the importance of reputational considerations and, therefore, causes an increase in the commission of acts that were regulated to begin with, or simply, conduct where Second, an increase in the breadth of antitrust law brings additional conduct under regulation, i.e., conduct in between and that reduces their commission. Rectangle I reflects this second change, which we could label the “regulatory expansion effect.” The overall impact of broadening a standard on the measure of noncompliant firms is, a priori, unclear. There is an increase in noncompliance if the stigma dilution effect dominates and a reduction if the regulatory expansion effect dominates. To investigate the relationship between these effects further, we first define the measure of compliant firms as:

M(ts)≡F(b∗(ts),ts)

Therefore, the impact of enhancing the scope of enforcement is given by:

M′(ts)=Fb(b∗(ts),ts)b∗ts(ts)+Ft(b∗(ts),ts)

This expression simply formalizes the two effects illustrated in Figure 2, where the first term captures stigma dilution and the second term captures the increased compliance due to the regulatory expansion. Next, we construct simple examples to demonstrate how the first effect can, perhaps counterintuitively, dominate.

D. Examples

Let us consider a very simple example where we normalize the maximum benefit from noncompliance to 1, and are uniformly and independently distributed, enforcement occurs with certainty (i.e., and we set and Moreover, to further simplify the analysis, we assume that:

q(b,t)={1ift>0.30.7ift≤0.3

Given these specifications, we first present a graphical representation of the equilibrium condition:

b∗=br(¯ς(ts,b∗))

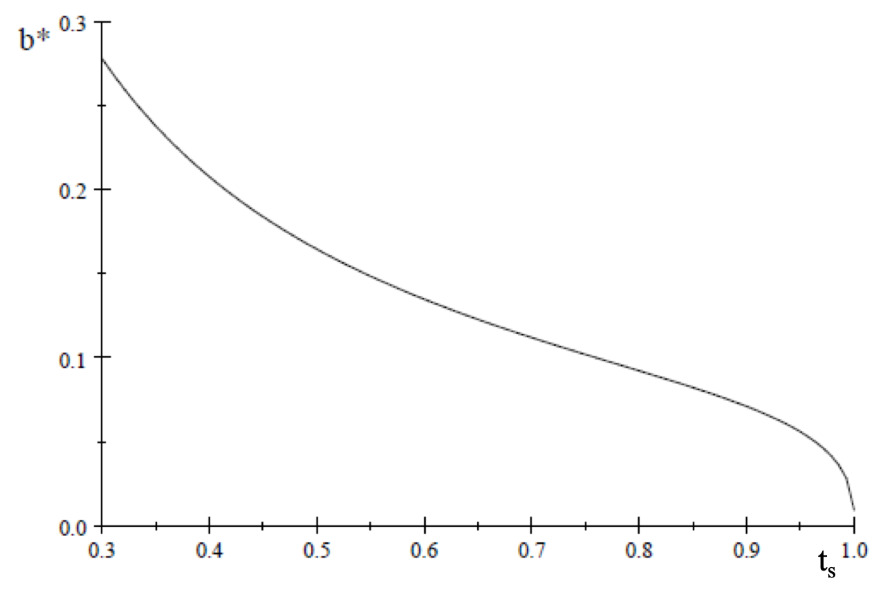

that emerges when the consumer welfare standard is used (i.e., as well as when it is slightly broadened (i.e., via Figure 3, below. The figure depicts the left-hand side of equation (12) with the diagonal curve in black, the right-hand side under the consumer welfare standard in green, and the right-hand side under the broader standard in red.

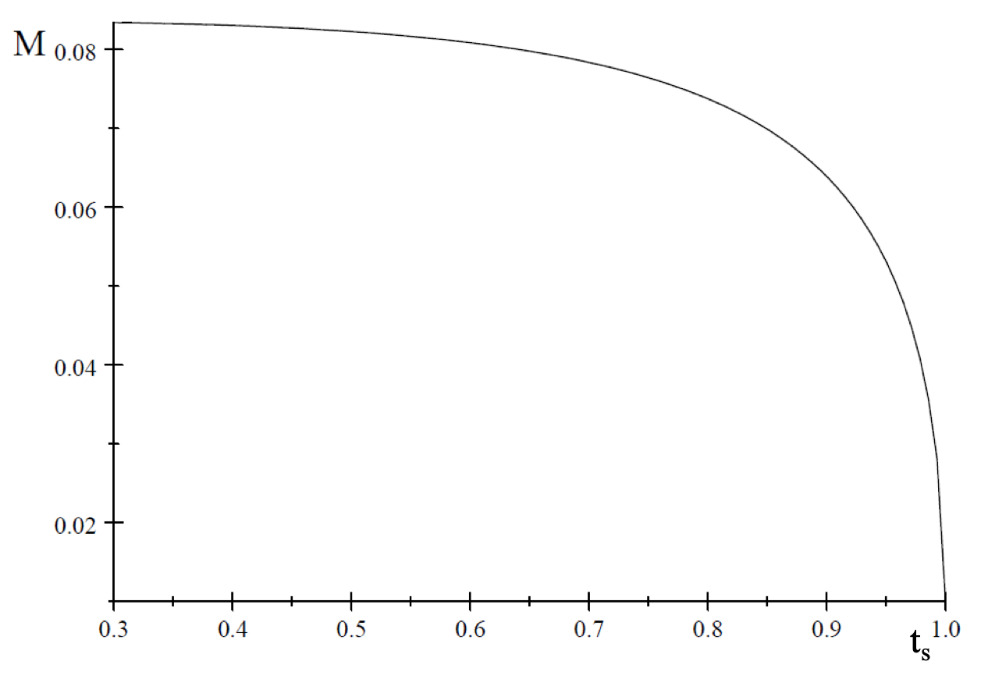

The figure illustrates the reduction in equilibrium incentives: moving from the consumer welfare standard (green) to one that enhances the scope of enforcement (red), reducing the equilibrium compliance rate from about 28% to about 21%.[145] This difference entirely results from a reduction in equilibrium reputational incentives, as the formal sanctions in the two cases are equal. However, the same broadening of standards also deters 21% of the conduct, which is not harmful to consumers but is now regulated through antitrust enforcement, i.e., Having depicted how the equilibrium compliance rate changes discretely in Figure 3 through a shift in the best response curve we next plot (in Figure 4, below) the equilibrium compliance rate as a function of the standard [146]

Figure 4 demonstrates that the reduction in incentives to comply due to a broadening of the scope of enforcement is not local but global.

Finally, as we have noted, an increase in the scope of enforcement causes two countervailing effects for the measure of compliance. First, it causes a reduction in the equilibrium cut-off in other words, it reduces the incentives to comply, given that the conduct is illegal. However, it also enhances the scope of enforcement and thereby incentivizes noncommission of the marginal conduct (i.e., Thus, we plot the measure of compliance as a function of the enforcement standard in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5 demonstrates that enhancing the scope of enforcement can reduce the overall amount of compliance by diluting reputational incentives, despite leading to the deterrence of new, non-welfare-reducing conduct.

IV. Discussion

In this Part, we discuss additional factors that ought to be incorporated when considering the social desirability of broadening antitrust standards, as well as extensions of our analysis. Specifically, we note that in addition to the rate of compliance, the social desirability of policies may be a function of the importance of deterring some types of conduct versus others. If harms to consumers are particularly important to avoid, then deterrence of additional conduct ought to be properly discounted. We explain this point in greater detail below, where we highlight an implicit assumption maintained throughout our analysis, namely that reductions in deterrence are undesirable. We explain that this is likely true when enforcers can adjust both the enforcement standard and the probability of enforcement. Finally, in the last Section, we explain the more general implications of the stigma dilution effect for antitrust enforcement and policies with a specific focus on evidentiary burdens.

A. Weighing Conduct

Part of our previous analysis questions whether broadening the scope of antitrust laws may increase the commission of conduct that reform proponents find harmful, either because they are harmful to consumers or due to other reasons. We answer this question affirmatively.[147]

Although this is an important question, it ignores the reality that not all conduct need be equally harmful, regardless of who measures the harm. In other words, even reform proponents may agree that increasing the number of acts that harm consumers by X in exchange for a reduction of X acts that are harmless to consumers—but implicate other considerations—may not be good trade.

Analytically, this amounts to attaching different weights to conduct. The more important the deterrence of a particular type of conduct, the greater the weight. This consideration can readily fit into our analysis by specifying a weight function which tracks the importance of deterring different types of conduct.[148] Using this approach, let us consider the objective or normative views of a person who considers acts that fall outside the scope of the consumer welfare standard to be harmful—but less so than those that fall within the scope of the consumer welfare standard. If so, then this view can be represented by a weighing function that is decreasing in that is, The objective would then be the minimization of the weighted average of conduct where gives the weight. An immediate result in this framework is that if the broadening of standards increases the measure of conduct committed, as in our example, then it is undesirable. In other words, an increase in the commission rate now becomes a sufficient (but unnecessary) condition to oppose increasing the scope of enforcement. This follows because the stigma dilution effect (reflected by rectangle S in Figure 2) “weighs more heavily” than the regulatory expansion effect (reflected by rectangle I in Figure 2).

B. Why Is It Desirable to Maintain Large Reputational Incentives?

The primary observation we made through our economic model is that increasing the scope of antitrust law through a broadening of the consumer welfare standard can dilute the reputational incentives provided to firms. We cautioned that this might give rise to a reduction in the deterrence of consumer-harming business practices.

Some may question whether a reduction in deterrence is necessarily bad. Specifically, one may ask whether the degree of deterrence we currently have is above the socially desirable amount, in other words, whether there may be overdeterrence, as the law and economics literature uses the term.[149] If so, is it not better to broaden antitrust standards, which will in turn reduce the degree of reputational incentives?

The response to this question comes from a simple insight by Gary Becker: if a reduction in deterrence is, in fact, desirable, a reduction in deterrence can follow from a reduction in the probability of enforcement, which would lead to social benefits in the form of reduced enforcement costs and efforts.[150] Thus, the optimal regime that employs the consumer welfare standard would be one featuring under rather than overdeterrence. Therefore, the deterrence reductions due to the stigma dilution effect are likely to generate further underdeterrence rather than correcting for existing overdeterrence.

C. A More General View of Stigma Dilution?

At the core of our observations lies the stigma dilution effect; broadening antitrust standards can reduce the reputational incentives of firms and thereby be detrimental to deterrence. We note that the relevance of this effect is not limited only to the policy changes that we discussed above. Indeed, any reform that reduces the informational value of antitrust enforcement can generate similar effects.

To illustrate, consider the evidentiary standards reductions we discuss in Section II.B. These changes are likely to increase the probability of wrongfully imposing liability on firms by reducing the evidentiary requirements for such findings. An increase in wrongful impositions of liability can have stigma dilution effects like those we model above and as noted in the prior literature.[151] Thus, the possibility of inadvertently reducing the deterrence of conduct harmful to consumers through stigma dilution should factor into discussions of reform proposals that seek to broaden the scope of enforcement—irrespective of the mechanism to achieve the goal.

This insight is relevant to other antitrust enforcement tools, too. For instance, if the usage of consent decrees makes information regarding the wrongdoings of a firm less salient to interested third parties,[152] then the use of consent decrees should weigh the stigma dilution effect of this policy tool against the cost savings generated.

V. Conclusion

The results from the model this Article develops lead to a clear suggestion: to maximize the reputational incentives of legal determinations, the law must base liability on dimensions that third parties care the most about. In the context of antitrust law, the use of consumer welfare—instead of metrics such as presumptions based on market concentration, impacts on the environment, income distribution, political groups, etc.—provides third parties—that is, the public—a clear measure of how liability is assessed. Without this clear signal, the deterrent effect of reform proposals to move away from the consumer welfare standard may plausibly result in more, rather than less, wrongdoing.

See, e.g., Elyse Dorsey et al., Consumer Welfare & the Rule of Law: The Case Against the New Populist Antitrust Movement, 47 Pepp. L. Rev. 861, 879 (2020) (“Experience over the last fifty years demonstrates that the consumer welfare standard has had a significant positive influence on antitrust jurisprudence and enforcement decisions.”); A. Douglas Melamed & Nicholas Petit, The Misguided Assault on the Consumer Welfare Standard in the Age of Platform Markets, 54 Rev. Indus. Org. 741, 749 (2019).

See, e.g., United States v. Cont’l Can Co., 378 U.S. 441, 444–46 (1964) (holding that the merger between a metal container supplier and a glass container supplier was illegal despite having shares of 33% and 9.6% in their respective container markets); United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., 384 U.S. 270, 272, 274 (1966) (ruling that the merger was illegal despite the combined firm having a 7.5% share of grocery sales in Los Angeles); see also Douglas H. Ginsburg & Joshua D. Wright, Philadelphia National Bank: Bad Economics, Bad Law, Good Riddance, 80 Antitrust L.J. 377, 382–86, 389–91 (2015) (detailing the rise and fall of structural presumptions in antitrust law).

See, e.g., Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 344 (1962) (“[W]e cannot fail to recognize Congress’ desire to promote competition through the protection of viable, small, locally owned businesses. Congress appreciated that occasional higher costs and prices might result from the maintenance of fragmented industries and markets. It resolved these competing considerations in favor of decentralization.”); FTC v. Fred Meyer, Inc., 390 U.S. 341, 348–50 (1968) (asserting that Congress passed the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, which addressed wholesale price discrimination, “to curb and prohibit all devices by which large buyers gained discriminatory preferences over smaller ones by virtue of their greater purchasing power” (quoting FTC v. Henry Broch & Co., 363 U.S. 166, 168 (1960))); see also United States v. Trans-Mo. Freight Ass’n, 166 U.S. 290, 323–24 (1897) (concluding that antitrust law exists to protect “small dealers and worthy men”).

See Utah Pie Co. v. Cont’l Baking Co., 386 U.S. 685, 692, 697–701 (1967) (preferencing competitors over consumers by condemning rivals’ attempts to compete with Utah Pie by lowering prices).

See, e.g., Christine S. Wilson et al., Recalibrating the Dialogue on Welfare Standards: Reinserting the Total Welfare Standard into the Debate, 26 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 1435, 1445 (2019) (“[T]he consumer welfare standard yields predictable results because the standard is implemented using sound economics.”); Joshua D. Wright & Douglas H. Ginsburg, The Goals of Antitrust: Welfare Trumps Choice, 81 Fordham L. Rev. 2405, 2406 (2013) (“The promotion of economic welfare as the lodestar of antitrust laws—to the exclusion of social, political, and protectionist goals—transformed the state of the law and restored intellectual coherence . . . .” (footnote omitted)).

See, e.g., Cont’l Television, Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36, 54, 58 (1977) (recognizing that vertical restraints can have procompetitive effects on interbrand competition that ultimately benefit consumers); Reiter v. Sonotone Corp., 442 U.S. 330, 343 (1979) (“Congress designed the Sherman Act as a ‘consumer welfare prescription.’” (quoting Robert Bork, The Antitrust Paradox 66 (1978))); Leegin Creative Leather Prods., Inc. v. PSKS, Inc., 551 U.S. 877, 889–90 (2007) (discussing how minimum resale price maintenance can benefit consumers); see also Donald F. Turner, The Durability, Relevance, and Future of American Antitrust Policy, 75 Calif. L. Rev. 797, 798 (1987) (“Antitrust law is a pro-competition policy. The economic goal of such a policy is to promote consumer welfare through the efficient use and allocation of resources, the development of new and improved products, and the introduction of new production, distribution, and organizational techniques for putting economic resources to beneficial use.”); Herbert Hovenkamp, The Rule of Reason, 70 Fla. L. Rev. 81, 118 (2018) (“[A]ntitrust’s consumer welfare principle . . . identifies antitrust’s goal as competitively low prices and high output, whether measured by quantity or quality.”).

See infra Section II.A.

Turner, supra note 6.

Wilson et al., supra note 5, at 1455.

C.f. Herbert Hovenkamp, Is Antitrust’s Consumer Welfare Principle Imperiled?, 45 J. Corp. L. 65, 66 (2019) (“[U]nder the consumer welfare . . . principle . . . antitrust policy encourages markets to produce output as high as is consistent with sustainable competition, and prices that are accordingly as low. Such a policy does not protect every interest group.”). Of course, error costs result from decision-making based on imperfect and incomplete information. This makes the information value noisier but, in and of itself, does not imply bias.

See, e.g., Edward Cavanagh, Antitrust Remedies Revisited, 84 Or. L. Rev. 147, 164–80, 184–85, 187–200 (2005) (detailing the debates regarding civil versus criminal actions, treble damages, and equitable remedies); Ken Heyer, Optimal Remedies for Anticompetitive Mergers, Antitrust, Spring 2012, at 26–28 (discussing the relative benefits and costs of structural versus behavioral remedies for mergers).

See, e.g., Barry C. Lynn, Breaking the Chain: The Antitrust Case Against Wal-Mart, Harper’s Mag. (July 2006), https://harpers.org/archive/2006/07/breaking-the-chain/ [https://perma.cc/X2QX-286K] (advocating for the breakup of Walmart to achieve the larger goal of “restor[ing] antitrust law to its central role in protecting the economic rights, properties, and liberties of the American citizen”); Zephyr Teachout, Corporate Rules and Political Rules: Antitrust as Campaign Finance Reform 39–40, 51–52 (Fordham L. Legal Stud. Rsch. Paper No. 2384182, 2014), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2384182 [https://perma.cc/ZKR2-TY9E] (arguing for a rejection of the consumer welfare standard in favor of promoting smaller-sized firms with proposals, such as unconditionally “enabl[ing] state Attorneys General and the FTC to break up limited liability companies over a certain size”).

See Joe Biden, U.S. President, Remarks by President Biden at Signing of an Executive Order Promoting Competition in the American Economy (July 9, 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/07/09/remarks-by-president-biden-at-signing-of-an-executive-order-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/ [https://perma.cc/TY4U-Y7RH]) (describing modern antitrust as a failed experiment).

See, e.g., Lina Khan, The New Brandeis Movement: America’s Antimonopoly Debate, 9 J. Eur. Competition L. & Prac. 131, 132 (2018) (“The . . . focus on ‘consumer welfare,’ . . . has warped America’s antimonopoly regime, by leading both enforcers and courts to focus mainly on promoting ‘efficiency’ on the theory that this will result in low prices for consumers. The fixation on efficiency, in turn, has largely blinded enforcers to many of the harms caused by undue market power, including on workers, suppliers, innovators, and independent entrepreneurs . . . .”); Jonathan Kanter, Assistant Att’y Gen. for Antitrust Div., Remarks of Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter at New York City Bar Association’s Milton Handler Lecture (May 18, 2022), (https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-jonathan-kanter-delivers-remarks-new-york-city-bar-association [https://perma.cc/L6A7-GCS4]) (describing the consumer welfare standard as “a wolf in sheep’s clothing”).

See infra Section II.B.3 for a discussion of the “protect competition” proposal; see also Kanter, supra note 14 (“[T]he goal of antitrust is to protect competition . . . . [T]he consumer welfare standard has a blind spot to workers, farmers, and the many other intended benefits and beneficiaries of a competitive economy. Senator Sherman himself expressed a goal of protecting not only consumers, but also sellers of necessary inputs . . . . We have heard . . . profound examples of how mergers have harmed individual workers and small business owners . . . .”).

See FTC, FTC–DOJ Merger Guidelines (Draft for Public Comment) 14–17, 23–28 (2023), https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/ftc-doj-merger-guidelines-draft-public-comment [https://perma.cc/FLC2-YU8P].

Id. at 2, 6 (asserting that a “structural presumption provides a highly administrable and useful tool for identifying mergers that may substantially lessen competition”).

See Federal Trade Commission and Justice Department Seek to Strengthen Enforcement Against Illegal Mergers, FTC (Jan. 18, 2022), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2022/01/ftc-and-justice-department-seek-to-strengthen-enforcement-against-illegal-mergers/ [https://perma.cc/NLU2-4U7P] (questioning the validity of an efficiencies defense). Compare id. at 33 (opening the efficiency discussion with the following warning: “The Supreme Court has held that ‘possible economies [from a merger] cannot be used as a defense to illegality.’” (quoting FTC v. Proctor & Gamble Co., 386 U.S. 568, 580 (1967) (alteration in original))), with U.S. DOJ & FTC, Horizontal Merger Guidelines 29 (2010), https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2010/08/19/hmg-2010.pdf [https://perma.cc/6F36-2RJ6] (opening the efficiencies discussion with the following acknowledgment: “Competition usually spurs firms to achieve efficiencies internally. Nevertheless, a primary benefit of mergers to the economy is their potential to generate significant efficiencies and thus enhance the merged firm’s ability and incentive to compete, which may result in lower prices, improved quality, enhanced service, or new products.”). Relatedly, in rescinding the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines (VMGs), the FTC Chair and several other commissioners criticized the Guidelines’ recognition of efficiencies and the incentive to lower prices due to the elimination double marginalization (EDM). See FTC, Statement of Chair Lina M. Khan, Commissioner Rohit Chopra, and Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter on the Withdrawal of the Vertical Merger Guidelines 3–4 (Sept. 15, 2021), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1596396/statement_of_chair_lina_m_khan_commissioner_rohit_chopra_and_commissioner_rebecca_kelly_slaughter_on.pdf [https://perma.cc/D2QA-7PSV] (“[E]ven if a merger does create efficiencies, the statute provides no basis for permitting the merger if it nevertheless lessens competition . . . . The VMGs’ reliance on EDM is theoretically and factually misplaced.”). In response, Shapiro and Hovenkamp find the position of these commissioners “baffling” and “flatly incorrect as a matter of microeconomic theory.” See Carl Shapiro & Herbert Hovenkamp, How Will the FTC Evaluate Vertical Mergers?, ProMarket (Sept. 23, 2021), https://promarket.org/2021/09/23/ftc-vertical-mergers-antitrust-shapiro-hovenkamp/ [https://perma.cc/FP5H-87TP].

See, e.g., Barak Orbach, How Antitrust Lost Its Goal, 81 Fordham L. Rev. 2253, 2253, 2275–76 (2013) (“[W]hile ‘consumer welfare’ was offered as a remedy for reconciling contradictions and inconsistencies in antitrust, the adoption of the consumer welfare standard sparked an enduring controversy, causing confusion and doctrinal uncertainty.”); Sandeep Vaheesan, The Profound Nonsense of Consumer Welfare Antitrust, 64 Antitrust Bull. 479, 479, 494 (2019) (“Despite being the prevailing wisdom, consumer welfare antitrust rests on a bed of nonsense.”).

See infra Section II.B.; Khan, supra note 14.

See, e.g., Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Act of 2021, S. 225, 117th Cong. §§ 2(b), 4(b) (1st Sess. 2021) (expanding the standard of liability for mergers from “substantially [lessening]” competition to “an appreciable risk of materially lessening” competition); American Innovation and Choice Online Act, H.R. 3816, 117th Cong. § 2 (2d Sess. 2021) (barring a host of conduct for certain digital platforms); Competition and Transparency in Digital Advertising Act, S. 4258, 117th Cong. § 2(b) (2d Sess. 2022) (compelling large advertising platforms to break up); Ending Platform Monopolies Act, H.R. 3825, 117th Cong. § 2(a) (1st Sess. 2021) (prohibiting designated platforms from owning businesses across different product lines).

C.f. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. v. FTC, 729 F.2d 128, 138–39 (2d Cir. 1984) (“Otherwise the door would be open to arbitrary or capricious administration of § 5; the FTC could, whenever it believed that an industry was not achieving its maximum competitive potential, ban certain practices in the hope that its action would increase competition.”).

See Platform Competition and Opportunity Act of 2021, H.R. 3826, 117th Cong. (1st Sess. 2021).

See John M. Yun, Discriminatory Antitrust in the Realm of Potential and Nascent Competition, CPI Antitrust Chron., Feb. 2022, at 1, 7 (“[P]roposed legislation like . . . [the] ‘Platform Competition and Opportunity Act,’ would treat market leaders [in music streaming] like Spotify significantly more favorably than lagging rivals Apple, Amazon, and Google . . . because Apple, Amazon, and Google fit some arbitrary definition of ‘big tech.’”).

See, e.g., Hovenkamp, supra note 10, at 93 (criticizing the neo-Brandeisian approach as assuming consumers are concerned about large firms when “to the best of my knowledge there are not even opinion polls indicating that people who understand the consequences would prefer a world of small but higher priced firms”).

See, e.g., Jonathan M. Karpoff & John R. Lott, Jr., The Reputational Penalty Firms Bear from Committing Criminal Fraud, 36 J.L. & Econ. 757, 758, 784 (1993) (“[W]e present evidence that the reputational cost of corporate fraud is large and constitutes most of the cost incurred by firms accused or convicted of fraud.”).

For instance, a criminal record makes it significantly less likely that a potential employer will interview or hire a worker. See, e.g., Harry J. Holzer et al., Perceived Criminality, Criminal Background Checks, and the Racial Hiring Practices of Employers, 49 J.L. & Econ. 451, 453, 455 (2006); Amanda Agan & Sonja Starr, The Effect of Criminal Records on Access to Employment, 107 Am. Econ. Rev., May 2017, at 560, 564.

While numerous studies examine the impact of antitrust investigations and violations on a firm’s financial performance, we are unaware of a study that isolates the reputational impact of antitrust verdicts. For instance, a firm found guilty of collusion can suffer a loss in valuation due to (a) the treble damages; (b) the loss in future profitability from not being able to collude; (c) the likely higher probability of being caught for violations; and (d) reputational costs. See Peggy Wier, The Costs of Antimerger Lawsuits: Evidence from the Stock Market, 11 J. Fin. Econ. 207, 207, 222–23 (1983) (finding antitrust prosecution in Section 7 cases results in “abnormal losses” in stock valuation where the “losses are consistent with the imposition of costly constraints on some defendants by government antitrust enforcers”); George Bittlingmayer & Thomas W. Hazlett, DOS Kapital: Has Antitrust Action Against Microsoft Created Value in the Computer Industry?, 55 J. Fin. Econ. 329, 339– 47 (2000) (examining antitrust enforcement actions against Microsoft in the 1990s and the impact on the computer industry as a whole). See generally Michael Cichello & Douglas J. Lamdin, Event Studies and the Analysis of Antitrust, 13 Int’l J. Econ. Bus. 229 (2006) (detailing various event studies associated with antitrust enforcement including the generally negative impact on stock valuations).

See infra Sections II.B.2–B.3. For instance, the Second Circuit held that the FTC “owes a duty” to make clear to businesses “an inkling as to what they can lawfully do rather than be left in a state of complete unpredictability.” E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. v. FTC, 729 F.2d 128, 139 (2d Cir. 1984); see also Broad. Music, Inc. v. CBS, 441 U.S. 1, 9 (1979) (noting courts require “considerable experience” with a practice before condemning it per se (quoting United States v. Topco Assocs., 405 U.S. 596, 607–08 (1972))).

See, e.g., John Armour et al., Regulatory Sanctions and Reputational Damage in Financial Markets, 52 J. Fin. & Quantitative Analysis 1429, 1429, 1440 (2017) (“We find that reputational losses are nearly nine times the size of fines and are associated with misconduct harming customers or investors but not third parties.”). Similarly, “researchers have found that reputational losses resulting from misconduct affecting a firm’s customers, suppliers, or investors are large and significant, whereas losses associated with misconduct involving third parties (such as market participants in general or the public at large) are small and insignificant.” Id. at 1429–30 (first citing Karpoff & Lott, supra note 26, at 757–802; and then citing Deborah L. Murphy et al., Understanding the Penalties Associated with Corporate Misconduct: An Empirical Examination of Earnings and Risk, 44 J. Fin. & Quantitative Analysis 53, 55–83 (2009)).

C.f. Robert D. Cooter, Economic Theories of Legal Liability, 5 J. Econ. Persps., Summer 1991, at 11 (1991) (“Legal scholars discuss at least three objectives of liability law: compensating victims, deterring injurers, and spreading risk.”); Richard A. Posner, An Economic Approach to Legal Procedure and Judicial Administration, 2 J. Legal Stud. 399, 405–06 (1973) (describing the effect of deterrence and the scope of liability on the law’s ability to compensate victims); Andrew I. Gavil et al., Antitrust Law in Perspective: Cases, Concepts and Problems in Competition Policy 69 (4th ed. 2022) (“An antitrust system, therefore, might aspire for its rules to: (1) minimize the likelihood of both under-deterrence of anticompetitive conduct and over-deterrence of aggressive, but competitive conduct; (2) establish clear, easily ascertainable rules; (3) authorize administrative or judicial law enforcement only under circumstances likely to produce results that are superior to reliance on markets; and (4) create an enforcement scheme that is relatively easy and cost effective to administer.”).

See infra Section III.A.

The idea that the realized outcome of a purposeful action can differ substantially, and unexpectedly, from the intended outcome is likely as old as time. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” is a clear application of the law of unintended consequences where one “intends only his own gain” yet is “led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” See Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations 400 (J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1910). Economist Sam Peltzman popularized its application to the effects of safety regulations. See generally Sam Peltzman, The Effects of Automobile Safety Regulation, 83 J. Pol. Econ. 677 (1975) (discussing empirical evidence that indicates drivers altered their behavior in the wake of automobile regulations).

See, e.g., William E. Kovacic & Carl Shapiro, Antitrust Policy: A Century of Economic and Legal Thinking, 14 J. Econ. Persps., Winter 2000, at 43, 44–58; William E. Kovacic, The Intellectual DNA of Modern U.S. Competition Law for Dominant Firm Conduct: The Chicago/Harvard Double Helix, 2007 Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 1, 17–31, 43– 44 (2007); Wright & Ginsburg, supra note 5, at 2409; Gregory J. Werden, Antitrust’s Rule of Reason: Only Competition Matters, 79 Antitrust L.J. 713, 726–37 (2014).

See, e.g., The Consumer Welfare Standard in Antitrust: Outdated or a Harbor in a Sea of Doubt?: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Antitrust, Competition Pol’y & Consumer Rts. of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 115th Cong. 3 (2017) (statement of Hon. Joshua D. Wright, Executive Director, Global Antitrust Institute), https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/hearings/the-consumer-welfare-standard-in-antitrust-outdated-or-a-harbor-in-a-sea-of-doubt [https://perma.cc/GHR4-8UKN]; id. at 3–4 (statement of Carl Shapiro, Professor, Haas School of Business at the University of California at Berkeley); id. at 2, 5–8 (statement of Diana Moss, President, American Antitrust Institute); Steven C. Salop, Question: What Is the Real and Proper Antitrust Welfare Standard? Answer: The True Consumer Welfare Standard, 22 Loy. Consumer L. Rev. 336, 348–49, 353 (2010).

C.f. Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust’s Borderline 2, 4 (Univ. Pa., Inst. for L. & Econ. Rsch. Paper No. 20-44, 2020), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3656702 [https://perma.cc/4KC3-EFF7] (“Most descriptions of the consumer welfare principle refer to prices: the goal of antitrust should be to combat monopolistic prices. Articulating the goal in this way raises conceptual problems when we think about suppliers, labor or others involved in production.”).

See United States v. Baker Hughes Inc., 908 F.2d 981, 990 n.12 (D.C. Cir. 1990) (“[T]he Supreme Court, echoed by the lower courts, has said repeatedly that the economic concept of competition, rather than any desire to preserve rivals as such, is the lodestar that shall guide the contemporary application of the antitrust laws . . . to make a judgment whether the challenged acquisition is likely to hurt consumers . . . .” (quoting Hosp. Corp. of Am. v. FTC, 807 F.2d 1381, 1386 (7th Cir. 1986))).

See, e.g., Salop, supra note 35, at 337–38 (“The true consumer welfare standard is indifferent to conduct that harms competitors—unless the conduct also likely harms consumers.”).

See, e.g., Elyse Dorsey et al., Hipster Antitrust Meets Public Choice Economics: The Consumer Welfare Standard, Rule of Law, and Rent-Seeking, Competition Pol’y Int’l Antitrust Chron., Apr. 2018, at 21, 30.

Arguably, the total welfare standard, which incorporates welfare gains to the firm(s) even if those gains are not passed through to consumers, better maps onto the notion of “efficiency.” However, the differences between the total and consumer welfare standards are a matter of degree rather than kind. See generally Kenneth Heyer, Consumer Welfare and the Legacy of Robert Bork, 57 J.L. & Econ., Aug. 2014, at S19.

See, e.g., Peter Dorman, Microeconomics: A Fresh Start 7 (2014) (“[E]conomics is organized around a few core ideas . . . concerned with a tightly defined concept of efficiency . . . .”); see also N. Gregory Mankiw, Principles of Economics 137–38 (6th ed. 2012) (“Consumer surplus measures the benefit buyers receive from participating in a market.”).

The policy push to incorporate income redistribution and other notions of equity into legal rules is a common one across the law. However, there is a compelling argument that legal rules should focus on efficiency—as the income tax and other mechanisms to transfer income are superior instruments to redistribute income. See Steven Shavell, A Note on Efficiency vs. Distributional Equity in Legal Rulemaking: Should Distributional Equity Matter Given Optimal Income Taxation?, 71 Am. Econ. Rev. Papers & Proc., May 1981, at 414, 416–17 (detailing how, in the model, “despite [an] imperfect ability to redistribute income through taxation, everyone would strictly prefer that legal rules be chosen only on the basis of their efficiency”); Louis Kaplow & Steven Shavell, Why the Legal System Is Less Efficient than the Income Tax in Redistributing Income, 23 J. Legal Stud. 667, 667, 669 (1994) (describing how “[i]n this article, we develop the argument that redistribution through legal rules offers no advantage over redistribution through the income tax system and typically is less efficient”).

See Steven Shavell, Foundations of Economics Analysis of Law 596–612, 647–60 (2004); see, e.g., Caroline Cecot, Efficiency and Equity in Regulation, 76 Vand. L. Rev. 361, 368 (2023) (emphasizing that “pursuing efficiency is not necessarily at odds with promoting equity”).

Compare John Kwoka, Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies: A Retrospective Analysis of U.S. Policy 126 (2014) (finding evidence of some post-merger price increases even with remedies), with Michael Vita & F. David Osinski, John Kwoka’s Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies: A Critical Review, 82 Antitrust L.J. 361, 363, 368, 385 (2018) (finding Kwoka’s study to be an insufficient basis to conclude that agencies are not properly preventing anticompetitive mergers).

Notably, Demsetz highlighted the error in comparing a current system, where all the benefits and costs of the system are observable, with an idealized alternative, where all the projected benefits are emphasized—and not the costs. See generally Harold Demsetz, Information and Efficiency: Another Viewpoint, 12 J.L. & Econ. 1 (1969).

See, e.g., Warren F. Schwartz & Gordon Tullock, The Costs of a Legal System, 4 J. Legal Stud. 75, 76, 78 (1975) (“[I]f the enforcement mechanism does not assure perfect accuracy, each party is subject to the risk of a sanction’s being wrongfully imposed even if he does not violate the governing rules (‘the costs of error’).”).

See generally Frank H. Easterbrook, The Limits of Antitrust, 63 Tex. L. Rev. 1 (1984) (detailing the various social costs associated with false positives and negatives in antitrust law).

See, e.g., A. Douglas Melamed & Nicholas Petit, The Misguided Assault on the Consumer Welfare Standard in the Age of Platform Markets, 54 Rev. Indus. Org. 741, 746 (2019) (explaining that the consumer welfare paradigm “provides a criterion to guide the formulation and case-by-case application of the specific rules that are used to identify prohibited, anticompetitive conduct”). For instance, after a string of losses challenging hospital mergers in the 1990s, the then FTC Chairman Timothy Muris formed a task force in 2001 to examine the outcome of various hospital mergers. Agency economists conducted a series of merger retrospectives that revealed a key finding: the courts were permitting anticompetitive mergers. This task force was part of a fundamental transformation in the economics of hospital mergers along with the development of new tools and empirical methods. These changes led to a series of FTC victories in court. See Paul A. Pautler, A Brief History of the FTC’s Bureau of Economics: Reports, Mergers, and Information Regulation, 46 Rev. Indus. Org. 59, 79–81 (2014).