I. Introduction

Is a global pandemic a sufficient impetus for agencies to use their emergency authority? Recent moves by the Supreme Court suggest not. In limiting the Occupational Safety and Health Agency’s (OSHA’s) ability to protect workplaces from an infectious disease, the Court attempted to characterize the threat posed by the COVID-19 risk as simultaneously too broad to constitute an occupational risk and too narrow to warrant an economy-wide mandate. In imposing narrow limits on agency action, the Court resurrected the specter of the major questions doctrine, which requires “Congress to speak clearly if it wishes to assign to an agency decisions of vast ‘economic and political significance.’”[1] This Article argues that whatever the general merits of the doctrine, focusing only on outcome-based limits for emerging risks is both unjustified and deadly. The inexpert second-guessing of emergency temporary standards (ETSs) by the Court costs lives.

In the face of emerging risks posing severe harm, agencies are granted emergency powers to act rapidly, if only temporarily. Congress allows OSHA to pass ETSs to address grave emerging risks before undertaking formal rulemaking and incurring the accompanying delay in regulatory protections. These expansive powers are temporary,[2] which protects against agencies using an ETS as a long-term substitute for a regulation based on the formal rulemaking process. Despite the established and acknowledged necessity of the ETS mechanism for agencies to address grave emerging risks, recent Supreme Court decisions threaten agencies’ ability to respond. The Supreme Court’s rejection of OSHA’s Vaccinate or Test ETS is a prime example of an under-rationalized and dangerous evisceration of agency authority. Scrutinizing only the number of workers affected by the standard, without reference to either the breadth of the risk or the delegation of power, the Supreme Court imposed an outcome-based limit exemplified by, though not limited to, the invocation of the major questions doctrine.[3]

While society has weathered prior infectious diseases—including the seasonal risk of flu—the transmissibility and potential severity of COVID-19 destabilized formerly normal interactions. The new risks associated with human contact—paired with the mandatory contact in a workplace—created an obligation for OSHA to act.[4] The fact that so little was known about COVID-19 meant that the agency needed to take initial action in the face of heightened uncertainty.

However, judicial review largely frustrated OSHA’s attempts to regulate COVID-19 risks. In staying OSHA’s ETS, requiring employees to either be vaccinated or mask/test, the Supreme Court ignored considerable agency fact-finding in favor of its own inexpert conjectures. While the majority does not explicitly invoke the major questions doctrine—though the concurrence does—the opinion can be viewed as an implicit endorsement of the doctrine’s application.[5] Substituting conjecture for evidence may serve to foster a broader legal agenda by limiting the nominal breadth of regulations an agency is allowed to impose. However, these nominal bounds can result in poorly tailored policies, depending on their relationship to the scope of the regulated risk. By ignoring the scope of risk posed by COVID-19 to workplaces engaged in social contact and attempting to appear to require tailored policies, the Supreme Court actually fails to uphold one.

This Article criticizes the Supreme Court’s treatment of agencies’ emergency authority for not only substituting conjectural judgements for agency factfinding but also jeopardizing agencies’ future ability to act swiftly in the next crisis. Scrutinizing the reasoning in NFIB v. Department of Labor, this Article interprets the provided rationales and distinctions as a smokescreen for an ideologically driven narrowing of agency action. This motivated reasoning—based implicitly or explicitly on the major questions doctrine—is inconsistent with the delegation of authority to agencies in the context of emerging risks.

Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) on occupational illness rates and occupational work activities, the Article presents novel empirical findings examining the risk posed by COVID-19 by industry. The results demonstrate that the threat of COVID-19 was not a risk specific to only one or two industries as the Supreme Court suggested. The empirical results also undermine the use of convenient industry-category distinctions by showcasing the considerable within-industry category variation in both illness rate percent changes and the importance of social contact for occupations in that industry. Finally, the analysis finds a positive and significant correlation between percent changes in illness rates and measures of social contact, supporting OSHA’s stated concern for jobs involving social contact.

Using these results, the Article discusses the proper evidentiary standard to which agencies should be held in coming crises and the danger of imposing elevated standards. As emerging risks will often occur on the “frontiers of scientific knowledge,”[6] waiting for perfect data to implement an ETS has high physical and health costs. In acknowledgement of the dangers of such delays, the Supreme Court has previously noted the great deference OSHA receives in its assessment of grave danger.[7] While making concrete suggestions for how OSHA could refine its analysis in future ETSs, the Article cautions against increasing the evidentiary burden in contexts with novel risks. It also notes that an outcome-based rubric for assessing the validity of agency action is not only legally unjustified, but will also systematically prevent agencies from fulfilling their obligations to deal with emerging risks.

The Article proceeds as follows: Part II outlines OSHA’s authority to promulgate standards for occupational safety and reviews the Supreme Court’s treatment of OSHA’s ETS on appeal. Part III critiques the Supreme Court’s treatment of the ETS as artificially narrowing the definition of an occupational risk, favoring reversible protection over long-lasting protection, and imposing inconsistent requirements relative to its treatment of other emergency measures. Part IV presents the results of an empirical analysis of occupational illness rates between 2019 and 2020 and suggests that the Supreme Court’s classification of industries with occupational COVID-19 exposures is underinclusive. Part V criticizes reliance on conjectural limitations to emergency regulations as not only legally unjustified but practically disastrous, resulting in insufficiently tailored regulations and unnecessary deaths.

II. OSHA’s Authority to Regulate Emerging Risks

Tasked with the ambitious goal of creating a safe workplace for workers, OSHA faced a novel challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic. OSHA’s overall responsibility for worker safety does not exclude illnesses or pandemics, for reasons well-illustrated by the current pandemic. While one might think that employees are sufficiently incentivized to keep themselves, coworkers, and customers safe, historically, this has not been the case. Given the politicization of COVID-19 restrictions,[8] employees who would benefit from wearing a mask may not. Their reluctance to do so may stem from a different set of risk preferences or from misinformation about the science of virus transmission. Similarly, employees may not have the means to protect themselves. At various points in the pandemic, people’s protection against COVID-19 depended in large part on the decisions of people in their surroundings. Accordingly, though some employees may prefer that they and their coworkers be subject to mask mandates,[9] they do not have the ability to enforce this as individuals.

Similarly, employers were under-incentivized to protect their workers. Employers may, all things equal, prefer that their employees avoid infection—non-sick workers miss fewer shifts and are more productive. However, this does not mean that employers are willing to sacrifice profits to keep their workers safe. An employer’s willingness to require workers to wear masks may not be enough to overcome anticipated backlash or enforcement costs. While workers may generally prefer to work in a safer environment, their reluctance to wear masks may outweigh the health-risk concerns. Fears of losing employees opposed to the measure may make an employer particularly reticent to deviate from industry norms. Add this general collective action problem to the politicization of COVID-19 risk reduction measures, and the potential importance of government intervention cannot be understated.

While the purpose of OSHA is only to protect employees—not clients (or the public at large)[10]—COVID-19 posed a unique risk to workers who had to work with one another or with members of the public. Such frequent and close contact, particularly with individuals about whom workers have limited or no understanding about exposure risk, carried a new risk of infection. Some workplaces have the capacity for remote work; however, other tasks are poorly done remotely. For these occupations, the alternatives to providing safe workplaces is “shutting down the economy” or letting the most vulnerable workers bear the burden of their poor immunity.

While the scope of OSHA’s protection is limited, its powers to effectuate workplace safety are expansive, particularly in cases of emerging risks.[11] OSHA’s general powers allow it to promulgate standards for harmful physical agents to “most adequately assure[], to the extent feasible, on the basis of the best available evidence, that no employee will suffer material impairment of health or functional capacity even if such employee has regular exposure to the hazard dealt with by such standard for the period of his working life.”[12]

This statutory authority is quite broad. Prior to 2022, the Supreme Court articulated two principal clarifications of the agency’s authority. First, OSHA must demonstrate that the regulated hazard poses a “significant risk” to workers.[13] Once OSHA has established that the risk of harm is significant, it need not prove that the standards be justified by a cost-benefit analysis;[14] instead, the standards must merely impose requirements that are “feasible.”[15] Feasibility is distinct from a cost-benefit analysis in that the statute places “the ‘benefit’ of worker health above all other considerations save those making attainment of this ‘benefit’ unachievable.”[16]

In emergency contexts, OSHA can issue standards not through a proposed rule but through an ETS.[17] The former route goes through the notice-and-comment period (and/or a public hearing), while the second bypasses these formal procedures.[18] Instead, an ETS takes “immediate effect upon publication in the Federal Register if [the Secretary] determines (A) that employees are exposed to grave danger from exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful or from new hazards, and (B) that such emergency standard is necessary to protect employees from such danger.”[19] The designation of “grave danger” risk amounts to something of a higher level than “substantial risk.”[20]

While there are fewer procedural constraints, the agency does not have unlimited discretion to issue standards through an ETS; an ETS merely allows OSHA to move rapidly in the face of true crises. The ETS is not a permanent rule. After publication, the Secretary has six months to go through the usual notice-and-comment proceeding with the ETS serving as a proposed rule.[21]

OSHA issued two ETSs concerning COVID-19 in the workplace. The first targeted healthcare employers and focused mostly on modification of the workplace environment to reduce the risk of COVID-19.[22] The second ETS, which applied more generally to employers of one hundred or more workers, required workers to either be vaccinated or to mask/test. This Article will focus on the second ETS, which garnered most of the criticism and was the focus of the Supreme Court’s review.

A. OSHA’s Vaccinate or Test ETS

The second ETS issued regarding COVID-19 (hereinafter “Vaccinate or Test”) was introduced on November 5, 2021. The rule required employers with a total of one hundred or more employees at any time to mandate that their employees be fully vaccinated against COVID-19.[23] If a worker chose not to be vaccinated, they had to test weekly and mask in the workplace. The employer need not cover the cost of testing or masks but must allow for “up to four hours of paid time and reasonable paid sick leave needed to support vaccination.”[24] The choice to focus on larger employers, OSHA explained, was based on the administrative ease of identifying covered workplaces as well as the likelihood of having more workers at a given worksite.[25] The Vaccinate or Test ETS did not apply to “(1) [w]orkers who do not report to a workplace where other individuals are present or who telework from home; and (2) workers who perform their work exclusively outdoors.”[26] It did not exempt workers with prior COVID-19 infections, based on research suggesting that immunity depended on severity of illness and the (then-current) evidence that vaccination provided superior protection against infection than natural immunity.[27]

While OSHA acknowledged that it was a far-reaching mandate, it also noted that the impact of COVID-19 spanned “a wide variety of work settings across all industries.”[28] It reviewed data from a variety of state health departments[29] and peer-reviewed studies[30] documenting the spread of outbreaks through workplaces. The peer-reviewed studies often documented increases in illnesses in nonhealthcare industries where workers had considerable contact with either the public or coworkers.[31] OSHA concluded that certain characteristics, “such as indoor work settings; contact with coworkers, clients, or members of the public; and sharing space with others for prolonged periods of time,” put workers at risk of COVID-19 and suggested that “most employees who work in the presence of other people (e.g., co-workers, customers, visitors) need to be protected.”[32]

In issuing its Vaccinate or Test ETS, OSHA clearly addressed a risk that was significant and imposed requirements for which compliance is feasible. The Supreme Court gives scant quantitative guidance in ascertaining what constitutes a significant risk. In terms of quantitative bounds, the Court has suggested that when confronted by a one-in-a-thousand odds of fatality, “a reasonable person might well consider the risk significant and take appropriate steps to decrease or eliminate it.”[33] In contrast, a one-in-one-billion odds of fatality “clearly could not be considered significant.”[34] Despite this, the Court has stated that this requirement does not constitute “a mathematical straitjacket”; instead, some risks are “plainly acceptable” while others are not.[35] For emergency measures, the threshold for risk is higher still, as OSHA must show that workplaces face a “grave danger.”[36] While the Court’s guidance above refers to the “significant risk” standard, the evidence for COVID-19 is strong enough to likely satisfy the elevated standard for grave danger.

Prior jurisprudence has suggested that a relatively high rate of fatality or serious health effects can designate a risk as significant.[37] As a health risk, COVID-19 is relatively serious, particularly for unvaccinated people. COVID-19’s fatality risk range can be measured in many ways. The case fatality rate—the number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths divided by the number of confirmed cases—is likely an upper bound on the fatality rate, because it assumes that confirmed cases reflect all COVID-19 cases. At the other extreme, deaths per population may be a lower bound, using the whole population as the denominator. By November 2021, there were around 745,000 confirmed COVID-19 deaths in the United States[38] This results in a case fatality rate of between one and two in one hundred[39] and a population death rate of roughly two in one thousand.[40] While these aggregate figures ignore a lot of heterogeneity,[41] the range is well above the one-in-one-billion threshold the Supreme Court dismissed as being too small. Indeed, even the conservative measure is higher than the rate the Supreme Court cited as one in which “a reasonable person might well consider the risk significant and take appropriate steps to decrease or eliminate it.”[42] Given that the average occupational fatality rate in the United States (prior to the pandemic) was one out in twenty-five thousand people,[43] it seems incontrovertible that COVID-19 constituted a grave danger to workers.

B. The Supreme Court’s Non-Deferential Review

After OSHA issued the Vaccinate or Test ETS, many suits commenced to enjoin the standard. The Fifth Circuit stayed the rule,[44] and cases were consolidated in the Sixth Circuit. The Sixth Circuit denied the request for an initial hearing en banc; a three-judge panel then dissolved the Fifth Circuit’s stay.[45] Plaintiffs applied to the Supreme Court for an emergency stay of the rule.[46]

In reviewing OSHA’s standards, “[t]he determinations of the Secretary shall be conclusive if supported by substantial evidence in the record considered as a whole.”[47] In specifying the “grave danger” addressed by the ETS, OSHA seems to suggest that it encompasses both the initial COVID-19 infection and the serious consequences of such infection.[48] Despite this deferential standard of review, the Supreme Court granted emergency stay of the rule.[49] Its decision seems to be based on two main points.

First, the Court suggests that OSHA is only tasked with regulating risks that are unique to the workplace.[50] While OSHA notes that the risk of COVID-19 is not confined to the workplace, OSHA characterizes it as an occupational risk. The Vaccinate or Test ETS reasons that a risk’s existence outside of the workplace does not change the fact that it constitutes a grave danger to workers, nor does it release employers from their obligation to provide a safe workplace: “[T]here is nothing in the Act to suggest that its protections do not extend to hazards which might occur outside of the workplace as well as within.”[51] Rejecting this argument, the Supreme Court suggests that risks also faced outside the workplace cannot be considered occupational:

Although COVID-19 is a risk that occurs in many workplaces, it is not an occupational hazard in most. COVID-19 can and does spread at home, in schools, during sporting events, and everywhere else that people gather. That kind of universal risk is no different from the day-to-day dangers that all face from crime, air pollution, or any number of communicable diseases.[52]

It then qualifies this statement, saying: “Where the virus poses a special danger because of the particular features of an employee’s job or workplace, targeted regulations are plainly permissible.”[53] It offers as an example researchers who work with the COVID-19 virus or workers in “particularly crowded or cramped environments,” noting that the “danger present in such workplaces differs in both degree and kind from the everyday risk of contracting COVID-19 that all face.”[54]

Secondly, the Court places special emphasis on the permanence of the intervention. Unlike a fire or sanitation regulation, the Supreme Court notes, a vaccine mandate “cannot be undone at the end of the workday.”[55] This irreversibility seems to be important in qualifying OSHA’s ability to impose the mandate.

Gorsuch wrote in concurrence, basing his decision on the idea that this violates the major questions and nondelegation doctrines. Not only did Congress not give OSHA the authority to implement this Vaccinate or Test ETS, Gorsuch argued, but if they had done so, it would be an unconstitutional delegation of authority.[56]

By granting the emergency stay of the Vaccinate or Test ETS,[57] the Supreme Court did more than merely reduce the level of safety for workplaces across the United States. In dismissing the proffered scientific evidence in favor of its own conjecture, the Court created a dangerous precedent that will affect how evidence is valued and how agencies are allowed to respond to emerging risks.

III. Inexpert Conjectures

In its review of OSHA’s Vaccinate or Test ETS, the Supreme Court demonstrated a reliance on conjecture and unscientific rules of thumb, substituting its own instinctive judgment for the scientific evidence introduced by OSHA. In doing so, the Court imposes an overly narrow definition of occupational risk, scorns interventions that provide lasting protection, and implements reasoning that is inconsistent with its review of other agency rules.

Given that the reasons proffered for the Supreme Court’s distinction are not persuasive, these reasons seem to hide the underlying discomfort: that the regulation is far-reaching in effect. This Part discusses how the Supreme Court’s reasoning conflicts with prior OSHA regulation and current review of other agencies’ regulations. It observes that the flimsy reasoning masks the desire for nominally narrow regulation and discusses why this goal is scientifically and legally unjustified.

A. A Litany of Unconvincing Distinctions

1. Restricting the Scope of Occupational Risks

As noted in Section I.B., a central reason for the Supreme Court’s decision to stay OSHA’s Vaccinate or Test ETS was its definition of an occupational risk. Correctly noting that OSHA only has authority over occupational risks, the Supreme Court contends that COVID-19 constituted a risk common to everyday life, not merely an occupational risk. “The Act,” notes the Court, “empowers the Secretary to set workplace safety standards, not broad public health measures.”[58]

While dismissing COVID-19 generally as a public health risk,[59] the Supreme Court does admit that COVID-19 can be an occupational risk when the workplace risk “differs in both degree and kind from the everyday risk of contracting COVID-19 that all face.”[60] Examples provided of such workplaces included researchers working directly with the virus or workers in particularly cramped environments.[61]

This reasoning is puzzling for two reasons. First, in defining occupational risk as requiring a difference in “degree and kind from the everyday risk,” the Supreme Court creates a new and confusing qualification to OSHA’s authority.[62] It is not clear at what level of generality “everyday risk” is classified. Do the activities of the average worker in the regulated occupation/industry provide the reference point? If most construction workers also participate in recreational construction hobbies, is their occupational risk transformed into everyday risk? Or must the average U.S. resident encounter the risk for it to qualify as an everyday risk? If the latter, arguably, many people who do not telework face a large proportion of their COVID-19 risk through their workplaces. If OSHA is required to prove that COVID-19 is not an everyday risk, does it need to establish that the average person chooses activities that limit their risk of COVID-19 (such as ordering groceries and necessities online, limiting their social contact in indoor spaces, masking, or bubbling) outside of the workplace?

While the occupation-specific distinction does not make sense in application, it also has not been previously imposed in practice. An occupational risk is not defined by dangers that are only encountered within the workplace but by whether workers are forced to encounter them within the workplace. As the dissent notes, unsafe drinking water and excessive noise are regulated by OSHA, despite these risks existing commonly outside the workplace.[63] Similarly, almost half of people aged 12–35 years are exposed to “unsafe levels of sound from the use of personal audio devices, and around 40% are exposed to potentially damaging levels of sound at entertainment venues.”[64] Despite the prevalence of this injury outside the workplace, OSHA is allowed to regulate excessive noise as an occupational risk. Finally, the fact that another agency regulates a toxic substance outside the workplace has not previously precluded OSHA from regulating it within the workplace. Formaldehyde is regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)[65] and the Consumer Product Safety Commission;[66] however, this does not prevent OSHA from regulating it in the context of the workplace.[67] This new qualification to occupational risks is inconsistent with OSHA’s longstanding recognized authority.

The second reason the Supreme Court’s definition of occupational risks is puzzling is that the science of transmission does not support the Supreme Court’s neat categories of occupations exposed to the “special danger” of COVID-19. The chief danger imposed of COVID-19 is contact with the virus, generally through infectious respiratory droplets being deposited on exposed mucus membranes in the mouth, nose, or eye through inhalation, splashes and sprays, or touch.[68] Moreover, at the time of the ETS publication and review, the CDC reported that infections can be transmitted even outside of six feet of an infectious person, particularly when “an infectious person exhal[es the] virus indoors for an extended time . . . leading to virus concentrations in the air space sufficient to transmit infections to people more than 6 feet away, and . . . to people who have passed through that space soon after the infectious person left.”[69] Given that researchers who work with the COVID-19 virus work with contained droplets, the chief cause of transmission (inhaling other people’s droplets) is not necessarily heightened in their context. In contrast, retail clerks who encounter hundreds of people per shift face the chief cause of transmission with every breath they take.[70] Moreover, such researchers have other sources of protection against interactions with COVID-19 samples (i.e., gloves and respirators within the lab). Other workers are not so well-equipped.

In narrowing the definition of occupational risks in ways that are inconsistent with OSHA’s demonstrated prior authority and the science of transmission, the Supreme Court dismisses an agency’s expert assessment of the scientific evidence surrounding transmission and replaces it with intuitive (but, based on scientific evidence, nonsensical) categories of risk.

2. Aversion to Irreversible Protection

The second motivating factor for the Supreme Court’s grant of the stay for the Vaccinate or Test ETS is that, unlike other OSHA regulations, a vaccination cannot be undone at the end of the day.

However, the Supreme Court does not explain why irreversibility is an undesirable trait. Indeed, it seems counterintuitive that a protection that extends beyond the workday is inferior to one that ends with the clock. Upon vaccination, all “costs” of the jab are completed, including the time to receive the shot, pain and suffering of the jab, and any associated side effects.[71] As such, the fact that protection endures past working hours imposes no new costs on a person: the continuing protection is an unambiguous benefit. Because vaccination is unlike other interventions for which the costs increase with time endured—such as the inconvenience of wearing protective equipment outside of the workplace—the appeal of reversibility in this context is bizarre.[72]

The strongest potential criticism relies on the existence of a reversible or time-limited alternate treatment providing a comparable or superior level of protection. Theoretically, by ignoring the reversible intervention and mandating the irreversible one, OSHA may correctly be accused of acting as a public health official, rather than as a workplace safety regulator. However, a reversible intervention providing comparable levels of protection as a vaccine did not exist at the time. Because of this, OSHA did not impose an insufficiently narrow regulation.

Further, spillover protections outside of the workplace have not seemed to be a consideration when determining the legitimacy of prior OSHA rules. Indeed, prior OSHA standards have required employers to offer hepatitis B virus vaccines to workers who have occupational exposure. While workers were free to decline the hepatitis vaccination (as in Vaccinate or Test), the fact that the standard involved a precaution that cannot be undone at the end of the workday was not disqualifying.

Notably, the Vaccinate or Test ETS allowed for an alternative (masking/testing) that could be reversed at the end of the day. Insofar as reversibility is a legal necessity—which it is not clear that it is—there is no requirement that the reversible alternative be the same cost as the irreversible alternative.

3. Inconsistent Reasoning for Other Emergency Measures

Finally, the Supreme Court’s inconsistent treatment of OSHA’s Vaccinate or Test ETS (relative to similar measures from health agencies) reflects its reliance on inexpert conjectures rather than on scientific data. On the same day that the Supreme Court stayed OSHA’s Vaccinate or Test ETS, the Supreme Court upheld the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMMS’s) interim final rule with comment period (IFC) requiring very similar COVID-19 restrictions.[73] This IFC was issued roughly around the same time as OSHA’s Vaccinate or Test ETS and required Medicare- and Medicaid-certified providers and suppliers[74] to ensure that their staff be vaccinated.[75] In describing the motivation for the rule, the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) notes that it is tasked with establishing “health and safety regulations for Medicare- and Medicaid-certified providers and suppliers.”[76] Accordingly, the rule is meant to “safeguard the health and safety of patients, residents, clients, and PACE program participants who receive care and services from those providers and suppliers.”[77] The chief danger the vaccination mandate attempts to address is transmission of the virus through unvaccinated healthcare workers.[78]

HHS does hint at other ways the vaccination policy affects the quality of healthcare services. It notes that the danger posed by unvaccinated healthcare workers is not merely as an infection vector but in interrupting access to healthcare. This occurs both through consumer hesitance to encounter unvaccinated staff and staff absences due to sickness.[79] HHS notes that while it has not previously required vaccinations for Medicare- and Medicaid-certified providers and suppliers, it has previously imposed other health and safety requirements regarding infection prevention.[80] Insofar as HHS discusses new variants of COVID-19 in its rule, it primarily notes that vaccines still impede transmission of the delta variant[81] and that the increased infectiousness of the delta variant provides motivation for more vaccinations.[82]

In contrast to its treatment of OSHA’s rule, the Supreme Court upheld HHS’s more stringent regulation on healthcare facilities. Like OSHA, HHS did not engage in notice and comment procedures in issuing the interim rule, reasoning that the onset of delta and the upcoming influenza season required quick action.[83] However, the Court held that HHS had good cause to do so.[84] More interestingly, the Court noted that the HHS Secretary had been authorized “to promulgate, as a condition of a facility’s participation in the programs, such ‘requirements as [he] finds necessary in the interest of the health and safety of individuals who are furnished services in the institution.’”[85] The Court also noted that, while the vaccine mandate is broader than prior infection control measures, the Secretary “has never had to address an infection problem of this scale and scope before.”[86] This acknowledgment of the breadth of the risk—and the need for a proportional response—is wholly missing from the Court’s review of the Vaccinate or Test ETS.

Of course, there are several reasons that may justify this difference in treatment.[87] First, as noted by HHS in its final rule, the purpose of each mandate is different. OSHA is tasked with ensuring safety and healthy working conditions for workers, and CMMS with safeguarding the health and safety of those receiving services from Medicare and Medicaid providers.[88] Because of this difference, considering risks to patients may create a stronger case for mandating vaccination. Imposing costs on healthcare workers to reduce harm to patients predominantly involves (1) reducing the risks of healthcare workers transmitting the virus to patients; and (2) preserving worker health to reduce interruptions of care.[89] Because this secondary effect is basically equivalent to OSHA’s goal, the main difference between the two rules’ purposes is HHS’s additional “reduce transmission to patients” goal. However, the duty to keep patients safe does not seem different from the duty to keep workers safe.

The second potential reason for the different treatment—one which has troubling implications—is that HHS’s IFC only governs one sector of the economy, while OSHA’s ETS is not restricted to any one industry. At first glance, it may seem that COVID-19 is a risk particular to a health workplace; indeed, HHS notes in its motivation that “[h]ealth care staff are at high risk for [COVID-19] exposure . . . due to interactions with patients and individuals in the community.”[90] However, the risk to workers in other industries is not necessarily qualitatively different. While people infected with COVID-19 do go to hospitals, it is not clear that other places of business do not face similar risks. This is particularly true given that evidence suggests that patients are most contagious two days before their symptoms develop.[91] Given that patients are instructed not to go to clinics unless the illness becomes too severe, and that most patients are contagious well before they realize they are infected, COVID-19 patients likely have contact with workers outside of the healthcare industry (by interacting with their own coworkers and interacting with the service industry).[92] And the ability to transmit COVID-19 in nonhealthcare workplaces seems, if anything, more likely, given the fact that healthcare facilities have upgraded ventilation, more access to PPE, and better training in health safety than most workplaces.

Finally, the Supreme Court seems to have considered whether the vaccine mandate was common to an industry. In upholding the HHS interim rule, the Court noted that “[v]accination requirements are a common feature of the provision of healthcare in America: Healthcare workers around the country are ordinarily required to be vaccinated for diseases such as hepatitis B, influenza, and measles, mumps, and rubella.”[93] Despite this, HHS has never previously mandated any vaccination—these requirements have been imposed by other entities, including employers.[94] This is not that distinct from OSHA’s new support for vaccination; even in this context, employers have always been free to require vaccination. Even if employer-imposed vaccination requirements are more prevalent within the healthcare industry, it is not clear why private company standards justify a vaccine mandate in one context but not another. More importantly, however, it is not clear why the custom of the regulated industry should define the tools an agency uses to regulate risk.

In articulating these unconvincing reasons for why OSHA exceeded its authority in addressing an infectious respiratory disease, the Supreme Court’s decision suggests that it merely sought to impose limits on agency action. The Supreme Court had never imposed nor articulated occupational restrictions in the past. Costless irreversibility had never been a negative attribute of protection in the past. And in contrasting the Supreme Court’s treatment of OSHA’s ETS with HHS’s industry-specific one, the Court seemed more willing to impose a heavier burden on the healthcare industry. These purported rationales seem in search of a narrow intervention, regardless of the scope of the risk. The following Section explains that this outcome-based rubric is not legally justified.

B. Motivated Reasoning for Narrow Regulation

The Supreme Court’s inexpert second-guessing of considerable scientific evidence sets a dangerous precedent for other agencies.[95] Generally, OSHA must only support its findings with substantial evidence[96] and is “not required to support its finding that a significant risk exists with anything approaching scientific certainty.”[97] Instead of abiding by this standard, the Supreme Court dismissed out of hand the idea that COVID-19 is an occupational hazard for workplaces with indoor social contact. In doing so, the Court characterized the circumstance as agency overreach while engaging in classic judicial overreach.

One way to understand the Supreme Court’s rejection of evidence in favor of conjectural limits—indeed, the way that Justice Gorsuch suggests should be the rationale—is that OSHA’s ETS violates the major questions doctrine. The major questions doctrine has been recently resurrected—cited not only by Gorsuch’s concurrence in NFIB v. Department of Labor but later by the majority in West Virginia v. EPA.[98] The doctrine allows the Supreme Court to question whether Congress intended to entrust a “policy decision of such economic and political magnitude to an administrative agency.”[99] This nominal cap of significance that subjects an agency’s decision to essentially fatal scrutiny is a particularly poor fit for emerging risks like the COVID-19 pandemic.

The major questions doctrine allows the Supreme Court to assess the legitimacy of a regulation based on the number of entities regulated, without considering the number of entities affected by the novel risk. This heuristic might make more sense with existing risks, for which the inference is stronger that Congress was aware of the specific risk and chose not to delegate it. However, for emerging risks this inference seems particularly weak.

Despite the Supreme Court’s sleight of hand, there is no serious argument that exposure to COVID-19 in the workplace is not an occupational risk.[100] If the route of transmission were coincidentally limited to a mechanism only found in select workplaces, there would have been no argument that OSHA was within its authority. However, the fact that COVID is transmitted through respiratory droplets is a mere accident of form. This feature does not change the nature of the risk posed to workers; it only changes the number of affected workers. When Congress delegates authority to an agency to protect a specific population (here, workers) from a risk (hazards in the workplace), it has no way of knowing the breadth of an impact the risk might have. This is particularly true for emerging risks: In delegating expansive emergency powers to be used temporarily, Congress knows that it entrusts to the agency a range of scenarios, some of which will affect very few entities, some of which will affect far more. Rather than developing a “distinct regulatory scheme” for addressing emerging risks, Congress has provided statutory authority to OSHA to address those risks comprehensively, though temporarily.[101]

Moreover, OSHA’s delegated emergency powers premise the validity of an emergency measure on the relationship between the intervention and the grave danger—an ETS must be necessary to address a grave danger affecting the workforce. Imposing a nominal cap on the magnitude of the intervention without considering the magnitude of the grave risk necessarily prohibits the agency from accomplishing its purposes for certain harms. Waiting for additional congressional action for large risks hamstrings the agency’s delegated authority in precisely the context where it is most needed. Indeed, interrelated risks that have the capacity to rapidly spread across different populations are precisely the ones for which agency action is relied upon for speedy government response.[102] Layering on an additional limitation prohibiting an agency from acting quickly when the affected entities are numerous actively works against the purpose of the delegation.

For the aforementioned reasons, the Supreme Court’s review of OSHA’s Vaccinate or Test ETS is both legally and scientifically unjustified. In order to accomplish its goal of cabining the scope of regulation—entirely independently from the scope of the regulated risk—the Supreme Court ignores the data presented to them and imposes inconsistent burdens on various agencies. The following Part empirically challenges the Supreme Court’s implicit assumption that the risk of COVID-19 is effectively addressed based on crude industry categories.

IV. Empirical Evidence Undermining Conjectural Limitations

In light of the Supreme Court’s dismissal of science in favor of stylized facts, this Part provides empirical evidence supporting OSHA’s claims that the risk of COVID-19 permeates workplaces outside of the healthcare industry. This empirical analysis produces three takeaways. First, many other industries, in addition to the healthcare industry, experienced a large percentage of increases in illness rates between 2019 and 2020. Second, while the exercise illustrates the challenge of characterizing risks by industry, it is feasible to demonstrate that the COVID-19 risks were sufficiently widespread that narrowing the scope of OSHA’s response was not warranted. Third, these percent changes are positively correlated with measures of social interaction, validating OSHA’s proffered rationale for the Vaccinate or Test mandate.

A. Linking Illness to Social Contact

This analysis uses publicly available data on annual illness rates detailed by industry. By linking government measures of the social contact for occupations to changes in industry illness rates, it is possible to establish the causal relationships that provided the rationale for OSHA’s ETS.

We use total illness rates[103] from the Bureau of Labor Statistics from 2019 and 2020.[104] Illness rate statistics are on a per 10,000 full-time worker basis, and consequently adjust for the number of workers in the industry and their time of exposure while working. We focus on the three-digit[105] North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) industry categories in the private sector and drop rates that do not “meet publication guidelines.”[106] While the total illness rates may include illnesses other than COVID-19, we use the percent change in these rates to measure the excess illness burden during the time of COVID-19.[107] Because we focus on changes in illness rates over time, the background average rates of illness will net out, and what remains is any change in the illness rate. We focus on the overall illness rate for a couple of reasons. First, for new diseases, such as COVID-19, it is not clear that those coding the diseases always were aware of how to code a novel illness. In case COVID-19 is coded as anything other than a respiratory illness, the total illness level will reflect this. Second, because the big health-related change in 2020 is the pandemic, we assume that the changes in the illness (not the injury) rate captures the excess illness of the pandemic. Third, and more practically, the finer categories are more likely to be censored as not meeting publication requirements of having enough observations in the cell so that confidentiality of the firm and the affected workers is preserved. Choosing a broad illness category ensures that we can observe as many industries as possible. By focusing on rates rather than the number of illnesses, the measures account for changes in the number of workers in different industries. We use, as our measure, the percent change in illness rate between 2019 and 2020 for each industry.[108] We use this metric because it better captures the relative change in illness rates compared to an industry’s historical experience. If OSHA’s assessment that illness rates from COVID-19 will arise from workplace contacts is true, then there should be an increase in the illness rate in industries in which the occupations involve more exposures to others.

We then classify industries by degree of risk from social contact. We do this by using data from categorizations developed by the U.S. Department of Labor and compiled in the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) data. O*NET publishes a list of occupations and ranks certain activities based on their importance to the occupation. O*NET lists occupations by Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code along with a factor between zero and one hundred indicating the importance of the activity to the occupation. To approximate the type of work that increases the risk of virus transmission, we use the following activities: assisting and caring for others; establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships; and performing for or working directly with the public.[109] The details of how we do this are listed in the Data Appendix. The principal measures of interest are the percent change in illness rates and corresponding importance scores[110] of the three work activities for seventy-one industry codes.[111]

B. Results Undermining the Supreme Court’s Conjecture

1. Broad Increases in Illnesses Rates Across Industry Type

Table 1 displays the industries with the ten highest percent changes in illness rates between 2019 and 2020 (in order from greatest to least). If an illness rate doubles between 2019 and 2020, the percent change is 100%. The nursing and residential care facilities industry has the highest percent change, accordingly, with illness rates that increased by roughly thirty times the original level—a startling increase. While the first, fourth, and eighth industries in the top ten are health-related—and accordingly are covered by the ETS that was not overturned—the remaining seven industries in the top ten would have been only covered by OSHA’s more general Vaccinate or Test ETS.

Retail trades dominate the chart as well: sporting goods, hobby, musical instrument, and book stores; food and beverage stores; motor vehicle and parts dealers; and furniture and home furnishings stores all join the list. Even within retail trade as a broad category, the marked increase for these sub-industries is consistent with the way people spent time during the pandemic. Furniture shopping skyrocketed, as people filled their time beautifying their home space and creating home offices.[112] Similarly, as people turned to crafting and at-home activities, hobby and book stores likely saw relatively more demand. While these may have been fulfilled through online orders, workers must still fulfill those orders in person. Food and beverage stores, number three on the list, are obvious—while many people ordered their groceries online, these orders were often fulfilled by other shoppers. And yet, many more continued to go to stores, with different levels of mask coverage.

Food manufacturing, which involves close quarters, also joins the list. Even though this industry is at the bottom of the top ten list, the illness rate experienced a roughly 284% increase. This corresponds to a 2020 illness rate that is roughly four times the rate in 2019.

2. Considerable Heterogeneity in Changes by Industry Category

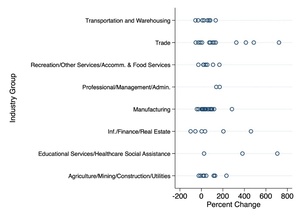

The pattern of changes in illness rates across the remaining industries is similarly informative. Dropping the two highest values from Table 1 for ease of visualization,[114] Figure 1 more closely examines the pattern of the remaining industries. The sixty-nine detailed industries are grouped into eight broader industry categories to visualize heterogeneity across industry type.[115]

Two conclusions become clear. First, while healthcare industries experienced big increases in percent illness rates during this period (including the observation excluded from Figure 1), it is not the only industry category to do so. All but twelve of the seventy-one industries experienced a positive percent change in illness rates. These fifty-nine industries constitute roughly 95% of the employment represented by the seventy-one industries.[116]

We can see how each industry falls on the spectrum of degree of change in illness rates. Industries with more than a 200% change in illness rates are not limited to healthcare; indeed, trade (encompassing both retail and wholesale trade) experienced big increases in illness. Other broad industry categories experienced increases of similar magnitudes, including information/finance/real estate, manufacturing, and agriculture/mining/construction/utilities.

Second, there is considerable heterogeneity in percent change in illness rate within broad industry type: while trade encompasses many of the largest percent increases, it also constitutes three of the twelve rates that experience percent declines. Delimiting risk exposure by broad industry categories—a distinction the Supreme Court seemed to make in its opinion—is accordingly not straightforward.

3. Illness Rate Changes are Positively Correlated with Measures of Social Interaction

To examine the factors that contributed to the change in illness rates, we use measures of social interaction that are reflective of OSHA’s concerns with workplace exposures. Table 2 lists the top industries for various work activity importance measures. To capture the social interaction infection vector, we consider the following activities: assisting and caring for others (Assisting and Caring); establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships (Interpersonal); and performing for or working directly with the public (Public). Looking at the categories demonstrates the different ways each activity captures social contact. Industry categories that are ranked in the top ten for two categories are marked by a single asterisk. Because each measure displays merely an aspect of social contact, the ramifications of the combined results are consequential.

Figure 2 plots the measures of illness on the y-axis and the average importance score for each work activity metric on the x-axis. Figure 2a displays the scores for Public, Figure 2b for Assistance and Caring, and Figure 2c for Interpersonal. Each dot represents a detailed industry, associated with a particular percent change in illness rate and importance score. Between Figures 2a, 2b, and 2c, the height of a given observation remains fixed (because each detailed industry is associated with a particular percent change in illness rate). However, where the observation falls on the x-axis will change with each graph, as its importance score varies with work activity. A linear prediction line is included on each graph as well, each showing a positive correlation between percent change in illness rates and work activity scores.

Notably, the x-axis displays a difference in the range of values for importance scores. The category for occupations based on their Public scores displays the largest range, with industry average scores below thirty and above eighty. Assistance and Caring has a similar range, but Interpersonal scores are concentrated between fifty-five and eighty. These scores have no cardinal meaning; however, they provide a measure of relative importance. The spread indicated on the x-axis shows whether there is a large spread across industries.

Figure 2 similarly displays how these broad industry categories rate on each work activity significance. Each broad industry category is represented by a different symbol. Industries with high Public importance scores seem to be disproportionately involved in trade and recreation/other services/accomm. & food services. For Assistance and Caring, educational services/healthcare social assistance does dominate, though trade and recreation/other services/accomm. and food services are not far behind. For Interpersonal importance, information/finance/real estate, educational services/healthcare/social assistance, recreation/other services/accomm. and food services, and trade all dominate.

Despite this, there is great heterogeneity even within broad industry categories. The cluster of each type of symbol varies by chart, but there is considerable variation in how each industry in a category values a particular activity. Broad industry categories do not fully capture the degree of social contact—and accordingly, risk—experienced by workers.

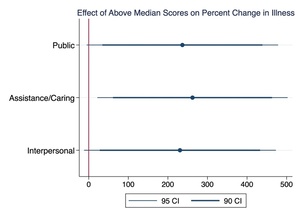

Finally, we divide the importance scores across industries into two groups. Industries are labeled as being above or below median for each work activity importance score. The correlation between being above median in each score and the percent difference in illness rates is plotted in Figure 3.[118] The point estimates are indicated by dots, and the 95% and 90% confidence intervals are indicated by the accompanying lines. An estimate is considered statistically significantly different from zero at the 5% (10%) level when the 95% (90%) horizontal line does not cross the vertical line (representing zero). This metric should be interpreted as the relative increase in the percent change in illness rates for industries that score in the upper half of the importance score for each activity.

The above graph indicates that the percent change in illness rates is roughly 200–300 percentage points greater for industries that score in the upper half of the importance scores.[119] All of the point estimates are significant at the 10% level and the Assistance and Caring metric is significant at the 5% level.

Our analysis does rely on industry as its unit of observation, a classification that the Supreme Court seemed to prefer in treating the HHS rule differently from the OSHA ETS. However, as noted above differentiating by industry is an uneasy fit with work activities. While this was necessary for our analysis based on the structure of publicly available OSHA illness data, government agencies could perform a similar analysis with more detailed data, particularly including information on occupation. Submission of such evidence could potentially be more persuasive to a court. Of course, given the Supreme Court’s analysis and resistance to regulations with a broad impact, it is not clear that more persuasive data would make a difference.

Despite the considerable data limitations of relying on publicly available information, the totality of these results support OSHA’s contention that COVID-19 risk is not solely confined to specific industries. What matters is not the stereotypical idea of which industries exemplify risky work activities but at which worksites those risky activities take place. Our analysis, combining different sources of data to characterize detailed industry by work activity, finds evidence of a correlation between work activities that involve social contact and elevated risks.

Dismissing the considerable scientific research OSHA presented regarding the scope of the risk of COVID-19 to workers, the Supreme Court substituted its own inexpert judgment for evidence. Our results confirm OSHA’s initial assessment, and the following Part warns of the more permanent danger of denying agencies their ability to act quickly in an emergency.

V. Fettering Emergency Powers in a Pandemic

Contrary to the Supreme Court’s narrow articulation of OSHA’s authority, OSHA is authorized to regulate grave dangers in a workplace. The evidence necessary to establish such risk/danger varies by circumstance; however, past precedent has made clear that OSHA need not jeopardize the safety of the workforce while waiting for perfect evidence in an emergency. Limiting this authority, either through an elevated standard of proof or a per se outcome-based limit on agency action, is particularly inappropriate for novel risks and will hamstring agency action at a time when it is most needed.

A. The Physical Price of a Heightened Evidentiary Burden

The lack of deference to OSHA’s factfinding creates a precedent that will delay future agency action precisely when swift action is necessary. Insofar as the Supreme Court’s motivated reasoning is due to the perceived inadequacy of OSHA’s evidence of the widespread risk, this heightened evidentiary standard conflicts with current jurisprudence on agency authority over novel risks and costs lives.

Because COVID-19 is a new hazard, current jurisprudence does not require that OSHA wait for the maturation of scientific knowledge to act.[120] The Supreme Court has previously rejected the notion that demonstrating significant risk of harm “require[s] the Agency to wait for deaths to occur before taking any action.”[121] While OSHA “findings must be supported by substantial evidence,” the agency may “regulate on the basis of the ‘best available evidence.’”[122] This leeway allows for flexibility, particularly in areas where “findings must be made on the frontiers of scientific knowledge.”[123] Indeed, “so long as they are supported by a body of reputable scientific thought, the Agency is free to use conservative assumptions in interpreting the data . . . risking error on the side of overprotection rather than underprotection.”[124]

Consistent with this jurisprudence, OSHA likely satisfied its evidentiary burden to justify the Vaccinate or Test ETS. As OSHA notes, COVID-19 was one of the first situations in which the agency was truly dealing with a new hazard: prior ETSs often involved updating beliefs about existing toxins. Accordingly, findings regarding the transmission of COVID-19 truly occurred on the “frontiers of scientific knowledge.”[125] In its ETS, OSHA spent considerable time reviewing reports of outbreaks in workplaces in a variety of industries, demonstrating that the risk was not limited to one or two industries. It also reviewed existing peer-reviewed studies noting the connection between outbreaks and occupations that involved social contact.[126] Requiring more evidence for truly novel risks would result in the very danger OSHA is tasked with preventing.

Despite this, the strategy for analyzing the connection between illness rates and social contact presented in Part III may aid OSHA in its future attempts to regulate occupational risks. The data used in our analysis became available around the time OSHA promulgated the ETS and shows a positive correlation between social contact and illness rate percent changes across industries on a nationwide scale, despite the use of only publicly available data. This statistical connection might be more persuasive to a court than isolated reports of outbreaks in a variety of industries. In considering the type of evidence OSHA should submit in the next emergency, however, our results demonstrate the danger of elevating conjectural categories over reality.

Indeed, insofar as OSHA has neglected to tailor its proposal, it is not in the way the Supreme Court has suggested.[127] Our results do not necessarily conform to the neat categories that the Supreme Court seems to value. The estimates of illness rates suggest that more than just health industries experienced large increases in illness during COVID-19, contrary to the Supreme Court’s suggestion. Our analysis also highlights the potential mismatch between industry classifications and worker activities (which generally vary by occupation). We use a sophisticated and empirically sound method to characterize industries based on the occupations they comprise, but it seems clear that the type of activity conducted by a worker—and accordingly, the types of risk that will characterize a workplace—are a function of both industry and occupation. Moreover, a workplace may encompass multiple occupations, and the risk for each will be influenced by the others. Given the complexity of how these classifications interact, tailoring based on industry (and, to a lesser extent, occupation) is often not going to be sufficient. Accordingly, the Supreme Court’s exemptions to the vaccine mandate based on convenient industry categories will often be overbroad or too narrow.[128]

Based on our empirical analysis, OSHA correctly identified social interaction as the vector of occupational risk. More information regarding the level of COVID-19 exposure in a given workplace was unavailable at the time. While “grave danger” is measured by actual exposure in the workplace,[129] measuring the level of COVID-19 in the atmosphere is not straightforward, nor is mapping these atmospheric levels into expected illness rates. Unlike other harmful substances, for which extant technologies can measure concentration, detection technologies are very new, and these data were not available to OSHA.[130] Accordingly, the vectors of transmission were the best measure of COVID-19 risk.

While greater quantities of high-quality data provide the most reliable basis for evaluating prospective occupational safety standards, waiting for such data can be fatal. In circumstances involving fast-spreading infection, using the best available data to motivate emergency measures can be better than waiting for better data. Weighing these tradeoffs for specific risks is outside of the scope of this Article, and indeed, correctly within the purview of OSHA.

B. Dangers of an Outcome-Based Standard

There are no ex ante limits on the scope of a workplace danger. As past experience is a particularly poor yardstick in cases of emerging risks, the unprecedented nature of the emergency cannot be used as a reason not to act. Rather than acknowledge that assessing the breadth of agency regulation must be in relation to the accompanying policy risk,[131] the Supreme Court imposed a crude, conjecture-based limit on the scope of OSHA’s response. Some dangers—like COVID—will permeate most workplaces. An outcome-based approach that requires that OSHA only issue narrow ETS’s will necessarily prohibit OSHA from fulfilling their statutory duty.

Insofar as these limits were based on the major questions doctrine, as suggested by Justice Gorsuch, this is even more problematic. Not only is the case for applying the major questions doctrine to emerging risks weak, for the reasons articulated in Section II.B, but the consequences are likely disastrous. The major questions doctrine will allow for narrow emergency measures but prohibit interventions with broad application. Insofar as populations—and, accordingly, the risks that they bear—are siloed, perhaps such a restriction will be less crippling. As the world becomes more interconnected, however, risks affecting large populations may become more prevalent. The major questions doctrine would hamstring agencies’ ability to address this growing set of risks.

Moreover, imposing outcome-based limits runs the risk of poorly tailoring regulations in the future by being too lenient for nominally limited interventions and being too stringent on nominally broad interventions. Insofar as the major questions doctrine subjects a particular intervention to heightened (if not fatal) scrutiny, it misses a lot of overbroad regulations below the nominal limit. For COVID-19, an infectious disease plaguing workplaces spanning industries, a broad solution was necessary to address the grave danger. For a more niche danger, a particularly narrow regulation will be sufficient. Restrictions based on a nominal cut-off will allow unduly broad regulation of narrow harms and insufficient regulation of broader harms.[132]

COVID-19 will not be the last emergency OSHA will face. The flexibility to make decisions despite the absence of years of evidence is indeed the purpose of an ETS; depriving OSHA of the right to use this tool in precisely the context for which it was created is perverse. Furthermore, imposing limitations on agency action based on preexisting notions of what constitutes normal regulation is particularly problematic in novel times. Frustrating agencies’ ability to adjust flexibly to evolving circumstances by judicial overreach only creates further vulnerability to future crises.

VI. Limiting the Danger of the Major Questions Doctrine

Restraining an agency in precisely the context that its emergency powers are necessary is a particularly harrowing display of judicial overreach. In dismissing OSHA’s proffered evidence that their Vaccinate or Test ETS was necessary to address the pervasive grave danger posed by COVID-19, the Court fixates instead on narrowing the scope of workers affected by the regulation. The validity of the scope of affected workers, however, is meaningless without reference to the number of workers endangered by the risk. In its single-minded mission to narrow the nominal regulation, the Court substituted its own conjectures regarding what occupational contexts posed pandemic risks rather than relying on the scientific evidence that OSHA presented to justify its ETS. This inexpert second-guessing sets a dangerous non-deferential precedent that frustrates agencies’ future ability to respond to emergency situations.

This Article demonstrates that this outcome-based perspective, particularly if motivated by the major questions doctrine, is not only legally unjustified but practically disastrous in the context of emerging risks. The application of the major questions doctrine to emerging risks is nonsensical when there is explicit delegation of emergency powers to agencies for the population in question (here, workers). These emergency powers provide additional deference to agencies for risks on the frontier of scientific knowledge.

The new empirical evidence presented in this Article undermines the Supreme Court’s conjecture that the risk of COVID-19 posed a grave risk to only one or two industries. By examining the percent change in worker illness rates in 2019 and 2020, it is possible to identify whether there was an increase in occupational illnesses. Although health care industries such as nursing and restorative care facilities experienced surges in illness rates, there was a more general rise in illness rates. Indeed, industries such as food and beverage stores experienced a steeper rise in illness rates than did workers in hospitals. Industries representing a substantial majority of workers exhibited a rise in illness rates. OSHA consequently was not unreasonable in issuing a broadly based ETS.

When dealing with future incidents of occupational exposures causing illnesses, it is feasible for OSHA to use our results and methodology to identify the industries and occupations where these types of interactions are most prominent. Making sound and prompt targeting decisions is quite feasible for illnesses with similar transmission mechanisms. Indeed, to the extent that future COVID-19 variants and other types of pandemics have transmission mechanisms similar to COVID, our results can be directly applicable. Alternatively, in justifying and targeting future efforts, OSHA could develop regulatory initiatives that are broad in their coverage but exempt occupational contexts where these types of interactions do not play a prominent role. However, the basis for this targeting must comport with actual evidence regarding occupational risks, not conjectural categories or the scope of prior regulation. The results presented here demonstrate that illness rates are positively related to whether the job involves working directly with the public, assisting and caring for others, or establishing and maintaining personal relationships. Absent a similar risk, our methodology—correlating occupation-based characteristics to examine changes in illness/injury rates—can also provide a more sophisticated basis for motivating even emergency measures.

This Article cautions against imposing a heavy burden on agencies to justify action in the face of emerging risks. Doing so produces a heavy death toll, a fact that the Supreme Court has previously used as a rationale for the heightened discretion an agency receives. The contexts in which OSHA contemplates issuing an emergency standard often involve situations in which systematic data for issuing a proposed standard are not yet available and may not even exist. When risks are novel and as widespread as COVID-19 proved to be, an ETS is precisely the regulatory tool necessary to navigate uncertain territory. The temporary nature of the standard not only disincentivizes misuse but requires an agency to update its initial approach as better information becomes available.

While COVID-19 presented a novel risk, the regulatory concerns it prompted will not be unique. Given the increasing interconnectedness of populations, future risks will be harder to silo. Fixating on the scope of intervention, without reference to the scope of the risk, will continue to hobble agencies’ abilities to quickly respond to emerging risks. The resurrection of the major questions doctrine in this context will lead to unnecessary deaths.

VII. Data Appendix

This Appendix presents the details of our empirical methodology for interested readers. First, we convert the importance data into a metric for a three-digit occupation code. O*NET generally uses Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) codes aggregated at the six-digit code level. Sometimes, however, O*NET lists an eight-digit code (involving nonzero decimals). For example, O*NET will sometimes list an importance factor for SOC 29-1141.01 instead of 29-1141.00. We treat the codes ending in “00” as aggregated at the six-digit SOC code level. We then take all codes involving non-zero decimals and construct an unweighted average at the six-digit SOC code level. In other words, we (hypothetically) average 29-1141.01 and 29-1141.02 to create the importance score for 29-1141. This is unweighted because we do not have employment data at this level of granularity. We only impute the unweighted average of nested categories if we do not have an existing six-digit SOC code. We are left with a list of six-digit SOC codes and their corresponding activity importance scores.[133]

To convert these factors for six-digit SOC codes into factors for three-digit SOC codes, we then construct three-digit occupation codes from all six-digit SOC codes (i.e., the three-digit code for 29-1141 is 29-1). We then use other Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data to create an employment-weighted average of all activity importance scores at the three-digit occupation code level. To do this, we need information on employment in each six-digit occupation codes. We do this by using the 2020 industry-occupation employment matrix, which lists employment for all occupations in a given industry (and vice versa).[134] We use total industry counts of occupational employment (i.e., the number of employees in each occupation over all industries) as frequency weights for creating weighted averages of importance scores for each broad three-digit occupation group. Some employment values are suppressed when the industry-occupation cell is confidential, has poor statistical quality, or represents fewer than fifty jobs. To account for this, when these employment figures are missing, we allocate thirty jobs to the cell.[135] We then round employment to the nearest integer to allow for frequency weighting.

Having calculated importance scores by three-digit occupation code, we then characterize industries by work activity importance by aggregating the importance measures by occupation into industry means. We do this by using the 2020 industry-occupation matrix to find the employment associated with each three-digit occupation within a three-digit industry. Using these employment numbers, we merge importance scores (by three-digit occupation code) to different industries. We then use employment in each occupation-industry cell as a frequency weight[136] to get a weighted average of importance scores by a three-digit industry code.

The strength of the aforementioned method is that it creates an estimate of activity importance scores at the three-digit occupation code level, preserving the most occupation observations. The method may seem a bit roundabout, however, because occupational employment is used to frequency-weight the scores twice, once over all industry levels and once at a specific industry level. An alternative way of constructing these scores is described below.

Here, we take the O*NET occupation scores at the six-digit occupation code (using the method described above) and merge these directly to the industry-occupation employment matrix. We then create an employment-weighted average to create activity importance scores for each three-digit industry code.[137] The difficulty here is that by merging in more detailed codes, employment in the industry-detailed occupation code is more likely to be censored. Accordingly, the other method may preserve more observations in calculating industry averages. The results using this method, however, are listed below and are roughly similar to the ones displayed in the main text.

As in Table 2, Table A1 lists the top ten detailed industries for each measure of social activity. Several industries appear in more than one category (indicated by one asterisk): clothing and clothing accessories stores; hospitals; sporting goods, hobby, musical instrument, and bookstores; gasoline stations; health and personal care stores; educational services; and religious, grantmaking, civic, professional, and similar organizations. Only one industry appears in all three measures (indicated by two asterisks): ambulatory health care services. Despite the different measure construction, many of the same industries are in the top ten, as in Table 2. For the Public measure, nine out of the ten industries overlap (though some are in different order). For Assistance/Caring, seven out of ten industries overlap, with eight out of ten overlapping for Interpersonal. This provides some confidence that, while there are small differences in the methods, results are largely consistent.

For Figure A-1, the counterpart to Figure 2, the results are broadly similar as well. There is no difference in the vertical placement of each datum point between these figures because the percent change in illness rate does not vary by methodology. The only dimension moving, therefore, is the point’s placement on the horizontal axis. Patterns in broad industry types look very similar across all three dimensions.

Finally Figure A-2 plots the effect sizes for the same analysis displayed in Figure 3. As before, the 95% confidence interval is displayed by the thin line and the 90% confidence interval by the thick line. The empirical specification is the same, and the measures represent the increase in percent change in illness rates for industries that score above the median in each measure. The effect sizes still range between 200 and 300 percentage points. All estimates are significant at the 10% level, while only the Public measure is significant at the 5% level. Apart from small, expected differences, the results are remarkably consistent with the main analysis.

Util. Air Regul. Grp. v. EPA, 573 U.S. 302, 324, 327–28 (2014) (quoting FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120, 160 (2000)).

29 U.S.C. § 655(c)(3).

See infra Section III.B.

29 U.S.C. § 651 (“The Congress declares it to be its purpose and policy, through the exercise of its powers to regulate commerce among the several States and with foreign nations and to provide for the general welfare, to assure so far as possible every working man and woman in the Nation safe and healthful working conditions and to preserve our human resources . . . .”).

See infra Section III.B; Nat’l Fed. Ind. Bus. v. Dep’t of Lab., 142 S. Ct. 661, 662–67 (2022) (per curiam).

Indus. Union Dep’t, AFL-CIO v. Am. Petroleum Inst., 448 U.S. 607, 656 (1980).

Id. at 655–56.

Lauren Aratani, How Did Face Masks Become a Political Issue in America?, Guardian (June 29, 2020, 5:00 AM), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/29/face-masks-us-politics-coronavirus [https://perma.cc/FF29-S5SJ].

A June 2021 poll by the Harris Poll found that 57% of adults surveyed either somewhat agreed or strongly agreed that employees (even if vaccinated) should mask at work. Am. Staffing Ass’n, 2021 Workforce Monitor: Masking Anxiety (June 2021), https://d2m21dzi54s7kp.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ASA-Masking-Anxiety-Summary-Report.pdf [https://perma.cc/P5B5-ZA5X].

OSHA has issued interpretation letters of its authority as excluding “injuries that may occur to members of the public because of employee actions.” Standard Interpretation Letter from Raymond E. Donnelly, Director, Off. Of Gen. Indus. Compliance Assistance, OSHA, to Henry J. Garbar (May 18, 1993), https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/1993-05-18 [https://perma.cc/84TN-UQ4F], or “merchant/customer relationship[s],” Standard Interpretation Letter from Richard E. Fairfax, Dir., Directorate of Compliance Programs, OSHA (Oct. 17, 2001), https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/2001-10-17 [https://perma.cc/SU5N-H8DG].

Indus. Union Dep’t, 448 U.S. at 656 (“Although the Agency’s findings must be supported by substantial evidence, 29 U.S.C. § 655(f), § 6(b)(5) specifically allows the Secretary to regulate on the basis of the ‘best available evidence.’ . . . [T]his provision requires a reviewing court to give OSHA some leeway where its findings must be made on the frontiers of scientific knowledge.”).

29 U.S.C. § 655(b)(5).

Indus. Union Dep’t., 448 U.S. at 639.

Am. Textile Mfrs. Inst. v. Donovan, 452 U.S. 490, 509–12 (1981). Indeed, this is a point on which one of us has criticized the lack of cost considerations. See W. Kip Viscusi & Ted Gayer, Safety at Any Price?, Regul., Fall 2002, at 54, 56. It is therefore striking that the Court’s treatment of the regulation violates even an economic standard of approval.

29 U.S.C. § 655(b)(5) (“The Secretary, in promulgating standards dealing with toxic materials or harmful physical agents under this subsection, shall set the standard which most adequately assures, to the extent feasible, on the basis of the best available evidence, that no employee will suffer material impairment of health or functional capacity even if such employee has regular exposure to the hazard dealt with by such standard for the period of his working life.” (emphasis added)).

Am. Textile Mfrs. Inst., 452 U.S. at 509–12.

29 U.S.C. § 655(b)–(c).

See id.

Id. § 655(c)(1).

Int’l Union, United Auto., Aerospace, & Agric. Implement Workers of Am., UAW v. Donovan, 590 F. Supp. 747, 755–56 (D.D.C. 1984), adopted, 756 F.2d 162 (D.C. Cir. 1985).

29 U.S.C. § 655(c)(3).