- I. Introduction

- II. The Drive Towards NIL: NCAA v. Alston

- III. The NCAA Fumbled the Ball

- IV. Ramifications of NCAA v. Alston on the Possibility of Student Athletes Being Paid to Play

- A. Student-Athletes Could Potentially Qualify as “Employees” Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

- B. The NCAA’s Restriction on Noneducation-Related Benefits May Violate Antitrust Laws

- C. Federal Legislation Is Needed to Wrangle NIL Regulations into Something Workable

- 1. The NCAA Punted the Ball to Its Member Divisions

- 2. Group Licensing Models

- 3. Federal NIL Legislation Has Been Teed Up in Congress—But Legislators Have Yet to Take a Swing

- 4. Student-Athletes Have Also Demonstrated Support for Federal NIL Legislation

- 5. Any Federal Solution Must, at Minimum, Level the Playing Field Across Different States

- V. Conclusion

I. Introduction

If you offer athletes stipends, then you’re into pay-for-play, and that’s the ballgame. People should realize that, and they should realize that amateurism never has been a sustainable model for a sports-entertainment industry. It wasn’t in tennis. It wasn’t in the Olympics. And it’s not in bigtime college sports.[1]

It has long been a familiar refrain: pay college athletes. Giant strides were taken in furtherance of this endeavor in June 2021, when the Supreme Court handed down the decision in NCAA v. Alston.[2] The unanimous decision included a denouncement of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) restriction of the ability of collegiate athletes to earn money off their names, images, and likenesses (NIL).[3] In accordance with this ruling, the NCAA provided only very limited interim guidance on NIL activity, leaving most of the specifics of NIL regulation up to individual states or, in the absence of state legislation, to individual schools.[4]

Although paying college athletes for NIL is the right decision, the fallout from NCAA v. Alston created an untenable landscape navigated blindly by all parties involved—athletes, schools, and boosters (who are potential sponsors). To date, thirty states have passed NIL legislation, with varying restrictions.[5] The collegiate sports landscape essentially transformed into the Wild West overnight with athletes, schools, and boosters scrambling to figure out what is acceptable and what is not. The local sheriff in town, the NCAA, has effectively abandoned its duties at this point and petitioned the federal government for help instituting uniform national NIL rules.[6] A myriad of legal issues are bound to arise out of this new rule change given the extreme lack of guidance on the topic, and several legislators have aired the possibility of passing a uniform federal law implementing NIL regulations.[7] Additionally, the Court’s opinion implied the possibility that revenue-generating student-athletes should also be able to garner a share of both league and school profits,[8] leading many people to speculate that this may lead to another legal challenge against the NCAA.[9] This Note argues that it is necessary to pass federal legislation regulating this area, or else collegiate sports and the collegiate landscape will be completely transformed—for the worse—into something unrecognizable.

Part II of this Note briefly discusses the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in NCAA v. Alston before Part III analyzes Alston’s ramifications by detailing the immediate effect of the decision and subsequent sporadic implementation of NIL regulations have had on the collegiate sports landscape. Part IV discusses the possibility that Alston opened the door to pay-for-play, and Part V concludes with a discussion about why federal legislation is needed to wrangle NIL regulations into something workable.

II. The Drive Towards NIL: NCAA v. Alston

The final, somewhat convoluted drive towards compensating players for their NIL began with a 2014 class action lawsuit in California by current and former athletes who played Division I football and basketball.[10] In addition to the NCAA, the plaintiffs sued eleven of the NCAA’s Division I conferences.[11] These athletes argued that the NCAA’s restrictions on the education-related benefits athletes received as part of their athletic scholarships violated federal antitrust laws by prohibiting college athletes from receiving fair-market compensation for their labor.[12] The federal district court in California delivered a win to both sides of the debate, holding that the NCAA could continue to prohibit noneducation-related benefits, but not education-related benefits.[13] The Ninth Circuit affirmed.[14]

A. Majority Opinion

The Supreme Court granted certiorari to consider the NCAA’s argument that it should be immune “from the normal operation of . . . antitrust laws” and that, at minimum, its “existing restraints” upon benefits should remain in place.[15] The Court began its analysis with a litany of descriptive imagery regarding the interrelation of collegiate sports and money in America and the inception of the organization ultimately known as the NCAA.[16] From its beginnings, the NCAA has taken the stance that college athletes should not be paid for their performances.[17] This is despite the multibillion dollar value of college sports and the millions of dollars paid out to NCAA commissioners, athletic directors, coaches, and assistants each year.[18]

Because the student athlete plaintiffs did not appeal the Ninth Circuit’s decision on noneducation-related benefit restrictions, the Court’s entire analysis centered on the NCAA’s argument that education-related benefits should remain prohibited.[19] First, the NCAA argued that the lower courts’ use of a rule of reason analysis to analyze the NCAA’s compensation restrictions was in error, as such restrictions should have been subjected to an “abbreviated deferential review” instead.[20] After some discussion on when it is appropriate to utilize the different forms of review for antitrust cases, the Court remained decidedly unpersuaded by the NCAA’s argument on this point because the dispute in question “present[ed] complex questions requiring more than a blink to answer.”[21]

The next argument addressed by the Court related to the NCAA’s implication of a precedent case that the NCAA viewed as “foreclos[ing] any meaningful review of [limits on student athlete compensation]” in the case at hand.[22] The precedent case, NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, analyzed the NCAA’s restrictions on schools’ abilities to televise football games.[23] The NCAA viewed Board of Regents as an express approval of the NCAA’s compensation restrictions imposed on college athletes, thus precluding the issue in Alston. The Court disputed this interpretation as too broad, finding that the decision related solely to television restrictions, and held that the analysis in Alston remained consistent with precedent, as Board of Regents “invoked abbreviated antitrust review as a path to condemnation, not salvation.”[24] Accordingly, the Alston Court viewed “a more cautious form of review” as appropriate when analyzing the NCAA’s anticompetitive arguments.[25]

After determining that the rule of reason standard remained the appropriate test for the antitrust challenge at issue in the case, the Court analyzed the district court’s application of the test (which the Ninth Circuit fully upheld).[26] The rule of reason analysis is effectively a three-part test: first, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the restraints in question have “substantial anticompetitive effect.”[27] Although this is an exceptionally high burden to meet, the plaintiffs here did so, and the NCAA did not seriously attempt to dispute the finding.[28] The burden then shifted to the NCAA to establish a procompetitive rationale for the restraints.[29] Finding that some of the NCAA’s restraints (such as the noneducation-related benefits) may have procompetitive effects, the Court moved to the final step of the rule of reason analysis.[30] In the third step, “the burden shifts back to the plaintiff to demonstrate that the procompetitive efficiencies could be reasonably achieved through less anticompetitive means.”[31] The Court agreed with the district court’s assertion that the restraints were much stricter than necessary, striking down the NCAA’s arguments that this holding would result in judicial micromanagement of the organization’s policies.[32]

Interestingly, in reference to the debate about amateurism in college sports, the Supreme Court pointed to Congress as the party responsible for the resolution of this issue.[33] The Court made this identification while acknowledging the implications of the fact that the NCAA itself was unable to conceive a standard definition of amateurism.[34] “Instead . . . the NCAA’s rules and restrictions on compensation have shifted markedly over time” and “the NCAA adopted these restrictions without any reference to ‘considerations of consumer demand.’”[35] However, the Supreme Court’s implication in Alston is that federal legislation is the best path forward for compensating college athletes and its ramifications on amateurism. As discussed in Part IV of this Note, federal legislation for collegiate athlete compensation may garner enough support to pass in the near future, as a half dozen proposals have been submitted over the past few years.[36]

B. Justice Kavanaugh’s Concurring Opinion

One of the most intriguing parts of Alston is Justice Kavanaugh’s concurring opinion and its ramifications on the future of pay-for-play. Justice Kavanaugh argued that “the NCAA’s remaining compensation rules also raise serious questions under the antitrust laws.”[37] “Remaining compensation rules” refers to the restrictions on noneducation-related benefits, which were upheld by the district court and not appealed by the plaintiffs.[38] However, Justice Kavanaugh noted that any such challenge to noneducation-related benefits should, in the future, be scrutinized under the same rule of reason standard applied in Alston.[39] As the majority discussed, this is the typical standard when analyzing compliance with antitrust laws.[40] Justice Kavanaugh then took it upon himself to apply the rule of reason standard to the NCAA’s remaining compensation rules and indicated his belief that the NCAA likely lacks “a legally valid procompetitive justification for [such rules].”[41]

Justice Kavanaugh reached this conclusion based upon several factors: (1) the NCAA’s control of the collegiate athletics market; (2) the NCAA’s acknowledgment that its noneducation-related benefits rules compensate athletes for their “labor at a below-market rate”; (3) athletes’ limited to no ability to negotiate with the NCAA about these rules; and (4) the fact that the NCAA uses athletes on effectively an unpaid basis to “generate billions of dollars in revenues.”[42] Justice Kavanaugh remained decidedly unpersuaded by the NCAA’s “circular” argument that such rules are legal “because the defining feature of college sports . . . is that the student-athletes are not paid.”[43] After pointing out that “[t]he NCAA’s business model would be flatly illegal in almost any other industry in America,” Justice Kavanaugh categorically concluded his feelings on the argument, stating that “[b]usinesses like the NCAA cannot avoid the consequences of price-fixing labor by incorporating price-fixed labor into the definition of the product.”[44]

The concurring opinion closes with an acknowledgement that the realities of opening the doors to pay-for-play would result in “some difficult policy and practical questions.”[45] Justice Kavanaugh suggests the possibility of both legislation and a collective bargaining agreement, as it is clear that such questions may need to be resolved outside of the courtroom.[46] Given the strong indications that the NCAA may be in further violation of antitrust laws as it relates to noneducation-related benefits, it will be interesting to see how soon relevant litigation appears before the Supreme Court once more.

III. The NCAA Fumbled the Ball

A. Twenty-Nine States Have NIL Legislation Currently in Place

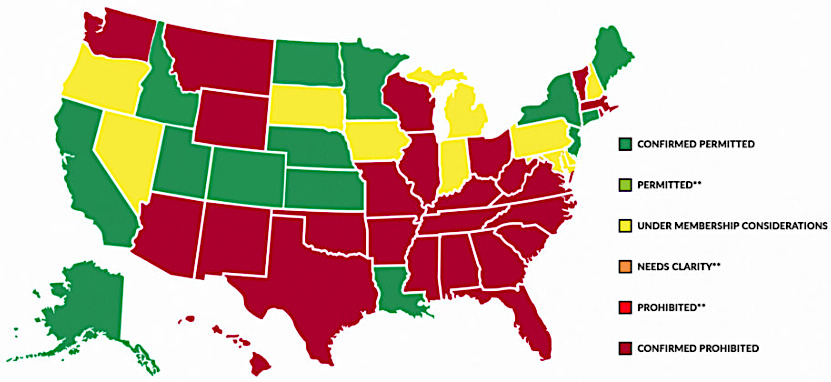

Following the issuance of the Alston decision on June 21, 2021, the NCAA subsequently approved a “uniform interim policy suspending NCAA name, image, and likeness rules for all incoming and current student athletes in all sports” on June 30, 2021.[47] The NCAA’s vote was timely, because the next day six states implemented the first series of NIL legislation.[48] To date, twenty-nine states have passed NIL legislation, and five additional states have pending NIL legislation in their current legislative sessions.[49]

Many states modeled their NIL legislation off California’s “Fair Pay to Play Act,” the first approved NIL law, which, while approved first, originally was not scheduled to go into effect until 2023.[51] Several other states also enacted NIL legislation with delayed effective dates in an apparent attempt to wait and see if the NCAA or Congress adopt a more long-term or federal solution.[52]

1. Key Differences and Ramifications

There are no major outliers among the various NIL laws enacted since Alston, but there are several key differences that already appear to be having an impact on athletic programs across the country. For example, several states explicitly extend NIL rights to high school athletes, while others either prohibit it or are silent.[53]

This already influenced the recruitment of one highly coveted high school quarterback in Texas, who graduated early from high school and enrolled at Ohio State University to take advantage of projected endorsements of over $1,000,000, in part because Texas prohibits NIL rights for high schoolers.[55]

Other states prohibit endorsements of product categories like alcohol brands, tobacco brands, gambling brands, or sports betting brands.[56] A prime example of a brand that arguably fits within at least one of these categories is Barstool Sports, which created “Barstool Athletes” as a sponsorship vehicle for any collegiate athlete who wishes for an endorsement.[57] Questions have arisen about student-athletes’ eligibility based upon how states view Barstool Sports’ support of alcohol and sports betting, and it is not entirely clear what repercussions will be for student athletes found to be in violation.[58] Perhaps, germane to their endorsements, Barstool Athletes have taken a gamble for what has so far been only deals for free Barstool merchandise.[59]

In an effort to maintain cohesiveness and a fair playing field among athletes, some states instituted provisions allowing schools to enact sharing agreements where certain percentages of a student athlete’s endorsement money must go into a fund for the rest of the team.[60] In states without such sharing agreements, some more prominent athletes have taken it upon themselves to share a percentage of their earnings with their teammates, a sign that NIL endorsements can affect the chemistry of a team.[61] One such athlete is former University of Georgia quarterback JT Daniels,[62] who signed a major preseason NIL deal with Zaxby’s, a national chicken finger restaurant chain.[63] In addition to sharing his Zaxby’s food allowance with teammates, Daniels worked to include a nonprofit element into each of his NIL deals, demonstrating a growing awareness by student athletes on the impact that they can make through such agreements.[64]

Illinois, Mississippi, and Texas implemented additional restrictive regulations, stating that athletes may be punished if they sign endorsement deals between the time of signing a scholarship agreement and actual enrollment at the university.[65] Another significant factor that has come into play, although not directly related to NIL laws, is the common restriction that many athletic programs enact forbidding freshman athletes from communicating with the media. Some schools are considering removing this restriction because student athletes view it as hindering their ability to garner public attention and therefore endorsements.[66]

2. Official NIL Ratings

It is clear that the NIL era has ushered in a major new factor for consideration in collegiate athlete recruitment. The National College Players Association (NCPA) is a prominent nonprofit group that advocates for collegiate athletes’ rights.[67] In an effort to support student athletes, the NCPA launched an “Official NIL Ratings” system to help athletes find states “with laws granting college athletes the greatest freedom to negotiate and sign NIL deals.”[68] The ratings are compiled via an analysis of twenty-one different factors, notably including: (1) whether the law allows athlete to receive free food, shelter, or medical expenses/insurance from a third party; (2) whether there is a cap that reduces or limits NIL pay per athlete; (3) whether the college can interfere with athletes’ freedom to participate in NIL deals; and (4) whether colleges are required to provide athletes with financial skills and information to help educate athletes.[69]

At the time of this writing, Illinois and Mississippi are tied with the worst rating at 43%, while New Mexico has the best rating at 90%.[70] Somewhat surprisingly, eight of the ten states with the worst ratings have schools in the Southeastern Conference (SEC), which routinely wins championships in a variety of Division I sports.[71] This may be a function of these states thinking that the recruiting negative of NIL restrictions is outweighed by the huge benefits of being a student athlete in the conference (such as professional prospects). However, this could change, because student-athletes will likely begin heavily scrutinizing such ratings systems in conjunction with scholarship offers from schools. To that end, Alabama also previously had a rating of 43%, but the state legislature voted to repeal the NIL legislation in early 2022, citing concerns that recruiting for state schools would be hindered by the too-stringent restrictions imposed by the legislation.[72]

3. Schools in States Without NIL Legislation

Regardless of how poor a state’s particular rating may be, the NCPA recommends that states should at least pass some minimum of NIL legislation to protect athletes’ rights.[73] For schools in states without NIL laws, student-athletes are only subject to the NCAA’s interim policy and the policies of their individual conferences and schools.[74] As a result, a more sporadic variety of policies have been implemented by schools lacking state governance. For example, Brigham Young University (BYU) enacted a deal for all of its football players to receive money from a protein bar company.[75] Indiana University created an NIL Directory comprised of student-athletes’ contact information to make it easier for sponsors to reach out to its athletes.[76] Many states with NIL legislation prohibit such involvement on the school’s part.[77]

B. Sample NIL Deals and Implications for the Future of College Athletics

Since Alston, athletes, schools, and boosters have been scrambling to figure out which NIL sponsorships are acceptable and which are not. Schools, and athletic departments in particular, quickly realized the necessity of providing education on the subject for both student-athletes and boosters so that their recruiting programs do not fall behind others. Texas Christian University’s (TCU) head football coach Gary Patterson communicated a potentially grave future for the TCU football program to local business leaders and program supporters, remarking that he “ha[s] a chance to lose 25, 30 guys” if the school did not get an NIL plan in place quickly.[78] Thus far, publicly announced NIL deals run the gamut from clearly serving as a recruitment tactic to functioning as a reward for players who have an impact on a team’s victory or success.[79]

Some schools, like BYU, have worked to compile endorsements for athletic squads as a whole in states that allow it.[80] The Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) organized an endorsement deal between TiVo Inc. and its football players, to which ninety of the team players signed onto and that has an estimated total value of “more than $100,000.”[81] In addition to the products received by the players in return for their promotion of TiVo, the company “provided the school an upgrade to its audio/visual equipment in some of the team facilities.”[82] The Ohio State University similarly entered into an agreement with The Brandr Group that any of the school’s student-athletes may opt into.[83] The agreement allows opted-in athletes to make money off of collaborations between Ohio State’s trademarks and licensees, such as the official school store selling jerseys with the athletes’ names on the back.[84] A group of University of Texas boosters affiliated with a nonprofit organization created “The Pancake Factory,” which will provide every scholarship offensive lineman on the football team roster with $50,000 annually in order to support charitable endeavors.[85] More recently, several members of football teams across the country simultaneously announced player-led NIL collectives, through which fans can subscribe to the collective and receive direct interactions with athletes in return.[86] Participating players split proceeds from the collective equally among themselves.[87]

1. NIL Deals Are a Gamble—But Boosters Indicate That They Are a Gamble Worth Taking

One of the first collegiate athletes to profit immensely off of NIL was former Oklahoma quarterback Spencer Rattler, widely viewed as a leading Heisman Trophy candidate entering into the 2021 football season.[88] Rattler locked up NIL endorsements for a reported amount of $200,000 prior to the season, only to underperform and find himself benched behind freshman quarterback Caleb Williams halfway through the season during the storied Red River Rivalry.[89] However, boosters did not seem to be worried—instead, they viewed it as an opportunity to present Williams with his own NIL deals.[90] It appears that sponsors are willing to take a risk that an athlete may not be the star they think he or she is, because the fact remains that a school’s supporters doling out money to athletes is a significant recruiting advantage for potential players.[91]

However, care needs to be taken in such situations, as Rattler subsequently transferred to the University of South Carolina during the offseason, and Williams entered the transfer portal in early January, although Williams initially acknowledged that remaining at Oklahoma was “definitely . . . an option.”[92] Many sports commentators believed that Williams’s entrance into the portal was his way of working the pseudo free agency created by NIL, although he ultimately followed his former Oklahoma coach to the University of Southern California—along with several other high-profile Oklahoma transfers and committed high school players.[93] It remains unknown the additional money promised to Williams via the NIL process to remain at Oklahoma or to transfer to USC, but it was likely significant, as a company backed by Eastern Michigan alumni offered him $1,000,000 (via Twitter, no less) to transfer there.[94] One method through which boosters may be able to hedge their investments in these types of situations is to structure NIL endorsements in a conditional manner, either based upon a period of time (such as a season) or based upon the student athlete remaining at the school in question.[95]

2. The Lack of Uniform NIL Regulations in Addition to the Transfer Portal Has Transformed the Transfer Process into Free Agency

Another example of an NIL-induced recruiting pitfall is the previously mentioned, highly touted Texas high school quarterback recruit Quinn Ewers.[96] As discussed in Section III.A, Ewers graduated high school early due to Texas’s rule against high school players cashing in on NIL deals prior to enrolling in college.[97] After taking only two snaps behind center for the Buckeyes during the 2021 season (both handoffs) and reportedly banking some significant NIL deals while in Ohio,[98] Ewers transferred to the University of Texas, where he joined his original recruitment class in January 2022 (i.e., the time he would have originally enrolled in college had he not graduated a year early to evade NIL restrictions on Texas high school athletes) with his full four years of eligibility and is set to compete for the starting quarterback position.[99] Although his new NIL deals associated with being a University of Texas football player are being kept secret, it is speculated that he is receiving several million dollars for his attendance based upon the value of the NIL deals he obtained at Ohio State.[100]

It is safe to say that Ewers’s decision to transfer shocked many Ohio State fans. However, that is the nature of the post-Alston world: players are beginning to treat the transfer portal as their entrance into free agency and using it to find destinations where they not only can get playing time but also rack up the most NIL endorsements.[101] This is evidenced by Caleb Williams’s use of the transfer portal in what some believed to be an attempt to drum up more NIL money from both Oklahoma boosters and boosters of schools in desperate need of a transfer quarterback.[102] The writing is on the wall, and there is nothing to be done to stop or limit this free agency train outside of federal legislation. This Note does not argue that the “free agency” effect is a bad thing—in fact, it may be a good thing, as proponents of this model would argue that college athletes are finally being compensated for their worth by universities. However, the leveraging of the transfer portal in this manner lends credence to the argument that student athletes are being paid to play under the guise of the current patchwork NIL regulations. It also raises questions about the amateur classification held by college athletes. With the pay-for-play and amateurism issues both coming into question as a result of the existing NIL landscape, and the NCAA deciding to largely stay out of the picture, the federal government is best suited to tackle the future of college sports.

IV. Ramifications of NCAA v. Alston on the Possibility of Student Athletes Being Paid to Play

Collegiate athletes gaining the ability to profit off their NIL is a huge victory, but the buck does not stop there. Athletes are now turning their eyes towards pay-for-play, arguing that they should receive portions of their schools’ and conferences’ profits generated off athletic contests.[103] The NCAA’s member schools generated over $18.9 billion in revenue in 2019.[104] Approximately $10.6 billion of that amount was generated by athletic departments.[105] However, pay-for-play may come at a steep price: the loss of the NCAA’s amateurism classification.[106] This classification is foundational to the current structure and organization of the NCAA and its member conferences:

The competitive athletics programs of member institutions are designed to be a vital part of the educational system. A basic purpose of this Association is to maintain intercollegiate athletics as an integral part of the educational program and the athlete as an integral part of the student body and, by so doing, retain a clear line of demarcation between intercollegiate athletics and professional sports.[107]

Foundational does not equate to being unchangeable. This point was driven home by Alston, which eroded restrictions that the NCAA clung to for decades as part of its amateurism model while questioning what the NCAA’s definition of amateurism even encapsulated.[108] The speed with which NIL endorsements have taken off since the floodgates opened in July 2021 indicates that there are boosters with large pockets itching to spend money on star athletes for their favorite teams; it is becoming more likely than ever that the NCAA’s amateurism model will be eroded even further, if not done away with completely, in the near term. Momentum for pay-for-play will continue to grow, particularly because the majority of college athletes are only receiving products in exchange for their endorsement, or very little amounts of cash.[109] Whether this goal is achieved via an antitrust challenge or through some other avenue remains to be seen.

A. Student-Athletes Could Potentially Qualify as “Employees” Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

In one active case, filed by current and former college athletes in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, the plaintiffs argue that they are employees, not amateurs, and thus are subject to the protections under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA).[110] The district judge recently certified the issue for interlocutory appeal, questioning “whether NCAA Division I student-athletes can be employees of the colleges and universities they attend for purposes of the FLSA, solely by virtue of their participation in interscholastic athletics.”[111] Given the Supreme Court’s skeptical dicta on the topic in Alston, the door is open to the possibility that Johnson will result in the decimation of the NCAA’s amateurism classification. If the court determines that the athletes are subject to the protections of the FLSA, schools (and potentially the NCAA) will be required to pay athletes a minimum wage and likely overtime for any work done in excess of forty hours per week.[112]

B. The NCAA’s Restriction on Noneducation-Related Benefits May Violate Antitrust Laws

Justice Kavanaugh’s Alston concurrence strongly indicated his belief that the NCAA’s prohibition on athletes’ receipt of noneducation-related benefits also violates federal antitrust laws.[113] His concurring opinion essentially invited potential plaintiffs to litigate the issue.[114] This concurrence is strengthened by the majority, which remained decidedly unpersuaded to extend any sort of antitrust exemptions to the NCAA.[115] In the event that the plaintiffs in the Johnson case are unsuccessful in receiving an employee classification under FLSA, antitrust litigation may be the next logical litigation avenue to be explored by collegiate athletes.

C. Federal Legislation Is Needed to Wrangle NIL Regulations into Something Workable

The patchwork of NIL legislation enacted thus far, and the confusion around such policies, also raises another issue: given the differences in NIL laws from state to state, there are concerns that athletes could get into trouble with endorsements that may extend across state lines.[116] Athletes and sponsors need to take care to follow the policies of the state in which the athletes are enrolled in school in order to avoid potential violations. There is a clear need for federal legislation to erase such potential speedbumps and make NIL deals and enforcement more predictable. Additionally, lacking more specific guidance and regulations on the process, athletes and sponsors are toeing a very fine line between compensation for NIL and pay-for-play, which remains prohibited under NCAA policies.[117] To this end, the NCAA reportedly probed the permissiveness of NIL deals for athletes at BYU and the University of Miami (both on a whole-team basis instead of looking at individual athletes’ deals) to determine whether pay-for-play violations took place.[118] The outcome of these investigations may be the first insight that athletes, schools, and sponsors have into what sorts of penalties may be imposed upon NIL violations (and what constitutes an NIL violation in the first place).[119]

Federal legislation is also needed to ensure an equitable playing field in collegiate sports as a whole. Although more skilled athletes will and should receive more valuable endorsement deals, the inability of athletes in certain states to profit in the same manner as their competitors—who may be participating in the same athletic conference—due to varying NIL restrictions in different states is something that should be rectified.[120] Otherwise, athletes like Quinn Ewers may leave their home state in order to pursue more favorable NIL opportunities elsewhere, leading to an exodus of talent from certain states. States have recognized this issue, as evidenced by Alabama repealing its NIL law, which, while passed early in the NIL era, became one of the most restrictive NIL laws in the country.[121] The regulation of NIL will become a race to the bottom as states work to offer the most freedom to athletes and schools.

The most obvious form of restraint to curb this issue would be to institute some sort of cap on noneducation-related benefits, such that athletes are not able to earn an unlimited amount of money in exchange for their performance.[122] However, such a cap would likely need to be instituted via legislation, as it is unclear whether it would pass the antitrust rule of reason analysis.

1. The NCAA Punted the Ball to Its Member Divisions

Recognizing the insufficiencies of its initial, interim NIL policy, the NCAA convened a constitutional convention in November 2021 to discuss potential rule changes and the organization’s future role as a governing body in this new landscape.[123] The new constitution was approved during the 2022 NCAA Convention in January 2022.[124] Effective August 1, 2022, the new constitution continues to bar pay-for-play benefits but punted authority to its three member divisions (Division I, Division II, and Division III) to develop their own respective budgets and control financial distributions among its member schools.[125] The result of this new constitution is the delegation of the NCAA’s authority to establish guidelines for NIL and other like rules to the respective divisions.[126] Depending on the extent of the measures each division takes, this delegation to the divisions may help solve some of the larger discrepancies among state NIL regulations. Speculations about what rules each division will adopt include the possibility of an entirely “new system of governance and rules enforcement”[127] and an adoption of a group licensing model (such as the one used by the National Football League).[128]

2. Group Licensing Models

Group licensing models “allow[] athletes to organize into a collective group and split revenue.”[129] Prior to the Alston decision, it was presumed that, to be a viable option in the NCAA, a player’s bargaining association would need to be established and federal legislation would need to be issued granting the NCAA antitrust immunity.[130] However, as discussed in Section III.B, group licensing deals are already being signed in the new NIL era absent both of these things. Instead of unionizing, group licensing deals have been procured by athletic departments on behalf of their programs (such as Ohio State’s agreement with The Brandr Group or the University of Texas boosters’ nonprofit for scholarship offensive linemen), or through marketing and branding companies such as Opendorse, which represents large numbers of athletes.[131]

Athletic conferences have also cashed in on these deals, with the Pac-12 conference allowing student athletes to “opt into a group licensing deal to use Pac-12 network footage and highlights.”[132] Such deals will likely gain in popularity because the athletes, schools, and conferences all profit off of them.[133] Importantly, these types of group licensing deals allow student athletes to profit off of their NIL using their school’s official trademarks and logos, which is something that was lacking during the first academic semester of NIL.[134]

Those who grew up in the early 2000s playing EA Sports’s NCAA Football video games might recognize the significance of group licensing deals—gamers may soon be able to play as their favorite college athletes once again, as EA Sports announced the revival of the franchise in February 2021.[135] Although this decision occurred prior to Alston, EA Sports indicated that it is keeping an eye on the progression of NIL regulations, and some schools have stated that they will only participate in the revived franchise if their student athletes are compensated for NIL.[136] The pushback from major universities will likely be impactful, as the reason that the EA Sports NCAA Football franchise originally went defunct was due to a lawsuit that EA lost, in which former college athletes sued for the unauthorized use of their NIL.[137]

3. Federal NIL Legislation Has Been Teed Up in Congress—But Legislators Have Yet to Take a Swing

Six federal bills (one of which was reintroduced seven months after it was initially put forth) have been proposed on this topic since June 2020, generated by players from both major political parties individually and also as a bipartisan effort.[138] This indicates the existence of an appetite to pass federal NIL legislation. However, the key may be whether some members of the House are willing to pass legislation solely dealing with NIL rules, or if legislators will be insistent on tying it to health and safety and Title IX-type rules as well.[139] Additionally, it is unclear what the timing would be on any proposed legislation, given the continuing COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with many policy issues relating to these major events taking precedence over collegiate sports. However, it is clear that some form of federal NIL legislation is necessary at this point given the chaotic landscape that the Alston decision and the NCAA’s hands-off approach has created.

The federal bills proposed to date contain many of the same components emphasized in state NIL legislation. For example, like many proposed and passed state NIL laws thus far, two of the federal bills explicitly propose prohibitions on endorsements related to tobacco, alcohol, drugs, gambling, or adult entertainment.[140] However, the majority of the proposals aim to provide more minimal restrictions on endorsements and instead link restrictions on certain industries to laws in the states in which athletes reside.[141]

On the other hand, as noted above, some of the proposals go beyond NIL and pay-for-play to also discuss Title IX and athlete health and safety.[142] The College Athletes Bill of Rights, the most comprehensive legislation introduced so far, would establish a “Medical Trust Fund” that not only covers athletes’ sports-related injuries but also any injuries or illness suffered by an athlete while an active college athlete.[143] The fund would be generated by required contributions from university athletic departments.[144] The Bill also seeks to establish a plethora of health, wellness, and safety standards, ranging from cardiac and brain health to sexual assault.[145] Not only is the College Athletes Bill of Rights the most comprehensive bill in terms of health and safety standards, but it also establishes a revenue sharing requirement between schools and athletes where scholarship athletes will be entitled to 50% of all annual revenue generated by the school’s athletic program (divided equally among athletes).[146]

Although the NCAA has been largely absent in the face of its interim policy, outgoing NCAA president Mark Emmert made a congressional appearance on September 30, 2021, making the case for “legislative assistance” in “providing a ‘federal framework’ around the NIL.”[147] Emmert specifically referenced the NCAA’s interest in normalizing NIL regulations versus the “patchwork” state laws that currently exist.[148] However, while the NCAA’s recently approved constitution contemplates cementing athletes’ ability to profit off of their NIL, it does not take the next step to document the intricacies of that ability.[149] The NCAA is visibly indicating its desire for the federal government to take these regulations to the next level and create a federal framework.

4. Student-Athletes Have Also Demonstrated Support for Federal NIL Legislation

Student-athletes from all fifteen Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) schools “wrote a letter to Senate Commerce Committee leaders in September [2021] urging them to enact a federal NIL bill.”[150] The athletes’ plea is based on the unfairness generated by the current NIL landscape, with some states lacking NIL laws and some states, schools, and conferences having more restrictive NIL laws than others.[151] These student-athletes seem to have the support of their conferences, as former long-term ACC commissioner John Swofford commented in 2019 that:

Realistically and practically, you can’t have 25 or 50 different state pieces of legislation on this particular issue . . . I’ve been doing this for about four decades now and I was never in the place where I felt like we needed federal intervention, but I think we’re maybe at that point.[152]

5. Any Federal Solution Must, at Minimum, Level the Playing Field Across Different States

If federal legislation does not get implemented soon, states with more restrictive NIL legislation or states with delayed effective dates for NIL legislation will likely revise such NIL laws to provide even more freedom, in order to be competitive with states like New Mexico. Alabama already proved this thesis when it repealed its NIL legislation in January 2022, explicitly with the goal of helping its state schools’ recruitment of athletes.[153] This relaxation effect could eventually result in minimal to no NIL regulations if left unchecked without a uniform federal solution. Additionally, student-athletes and sponsors may find themselves running afoul of existing regulations given the variance from state to state and the national branding of many sponsors. Many college football fans have taken it upon themselves to cry foul at situations they believe to constitute violation of NIL regulations, despite knowing little to nothing of what rules and regulations are actually regulating college sports currently.[154]

Any federal legislation should, at minimum, do more than continue to punt the issue of NIL regulation to the states. The goal of seeking federal legislation in this arena is to establish uniform rules governing NIL and other forms of collegiate athlete compensation. Allowing each state to set specific parameters on what types of NIL endorsements student-athletes may receive will only continue to exacerbate the current issues in college sports. This type of legislation would merely reinforce the current piecemeal aspect of NIL rules and continue to reinforce inequalities across different schools in different states—although this could change if the NCAA’s member divisions establish regulations governing each conference as a whole, such that schools in the same conference will at least be subject to the same regulations.

Given the transformative effect that NIL endorsements have caused on collegiate sports thus far, and the potential for pay-for-play allowed by the Alston decision, this Note suggests that any federal legislation on the topic should also consider the inclusion of compensation rules. The NCAA must adapt and modernize, and compensating student-athletes for their worth beyond NIL is a major step that will likely need to be taken as momentum for pay-for-play continues to grow. As one Senator who crafted proposed NIL legislation stated,

The college athletics industry created this problem by professionalizing itself over the course of years and one way or another, this is not sustainable because of public pressure—fans aren’t going to allow for the coaches and the schools and the companies to make billions of dollars while the students make almost nothing—or because the courts are going to step in.[155]

V. Conclusion

The Alston decision ushered in a new era of college sports. In the early beginnings of the NIL age, student-athletes, schools, athletic conferences, and sponsors have embarked upon the new frontier wholeheartedly. This understandable enthusiasm quickly exposed the multitude of issues associated with the current patchwork of deregulated NIL legislation. In order to protect student-athletes and the interests of smaller schools and conferences, federal legislation is desperately needed—legislation that provides uniform federal rules to ensure a level playing field is provided in this new era.

In light of Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence and disdain for what he deemed the NCAA’s inappropriate antitrust activities, it seems likely that a legal challenge to the NCAA’s prohibition on pay-for-play will make its way to the Supreme Court sooner rather than later. Because of this, and because the collegiate sport landscape is currently in a state of great flux, the federal government should aim to quickly pass legislation that, at minimum, establishes uniform national NIL regulations. However, given how fast things are moving, pay-for-play is a very real, near-term possibility, and the federal government should look to include compensation rules in any NIL legislation in order to streamline this process.

Laura C. Murray

Charles P. Pierce, History Drops Like a Bomb, Boston.com: Charles P. Pierce Blog (Sept. 14, 2011, 3:04 PM), http://archive.boston.com/sports/columnists/pierce/2011/09/history_drops_like_a_bomb.html [https://perma.cc/G4C9-9ZVS].

See generally NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141 (2021).

Id. at 2166 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring). “Name, image, and likeness rights are also frequently called an individual’s right to publicity. [Following Alston] NCAA athletes will be able to accept money from businesses in exchange for allowing the business to feature them in advertisements or products.” Dan Murphy, NCAA Name, Image, and Likeness FAQ: What the Rule Changes Mean for the Athletes, Schools and More, ESPN (June 30, 2021), https://www.espn.com/college-sports/story/_/id/31740112/rule-changes-mean-athletes-schools-more [https://perma.cc/7TKS-3TM8].

Michelle Brutlag Hosick, NCAA Adopts Interim Name, Image and Likeness Policy, NCAA (June 30, 2021, 4:20 PM), https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/news/ncaa-adopts-interim-name-image-and-likeness-policy [https://perma.cc/H246-MAXT].

Braly Keller, NIL Incoming: Comparing State Laws and Proposed Legislation, OpenDorse (June 27, 2022), https://opendorse.com/blog/comparing-state-nil-laws-proposed-legislation/ [https://perma.cc/M3T8-EZ68]. Of these states, Alabama repealed its NIL law in February 2022, citing its negative impact on Alabama universities’ athletic recruiting process. Id. Similarly, several others have amended or are in the process of amending their NIL laws in order to relax restrictions. Id.

See Hosick, supra note 4.

See Senator Cory Booker, Why I’m Behind the Athletes Bill of Rights, Sports Illustrated (Jan. 20, 2021), https://www.si.com/college/2021/01/20/cory-booker-athletes-bill-of-rights [https://perma.cc/G4Q2-PMFS] (“I do not have faith that the NCAA can be trusted to make the changes necessary . . . Congress must act to protect the well-being of college athletes.”); see also Steve Berkowitz, Sen. Chris Murphy Offers Bill to Help College Athletes Make Money From Name, Image, Likeness, USA Today (Feb. 4, 2021, 3:39 PM), https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/2021/02/04/chris-murphy-bill-name-image-likeness/4390593001/ [https://perma.cc/3SWV-GUDE] (“I love college sports . . . but it’s time to admit that something is very rotten when the industry makes $15 billion a year and many athletes can’t afford to put food on the table or pay for a plane ticket for their parents to see them perform.” (quoting Senator Chris Murphy)).

A concept known as “pay-for-play.” This model would compensate athletes “in amounts unrelated to their educational expenses.” Danielle Day, Pay for Play in College Athletics: Why Cost of Attendance?, 31 U. Fla. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 327, 345 (2021); see also NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2150–51 (2021).

Dan Papscun, College Athlete Pay Suit Confronts NCAA’s Supreme Court Loss (2), Bloomberg L. (July 6, 2021, 11:21 AM), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/college-athlete-pay-suit-confronts-ncaas-supreme-court-loss [https://perma.cc/6ZZL-5SMW] (“While the Alston decision on its own doesn’t mean pay-for-play is suddenly on the table . . . lawyers for the student-athlete plaintiffs in the case contend it stripped away the main defense the NCAA used to convince courts in past FLSA litigation not to implement tests to determine whether collegiate athletes are in fact employees.”).

See In re NCAA Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058, 1061, 1065 (N.D. Cal. 2019). The NCAA is comprised of three member divisions: Division I, Division II, and Division III. Division I is generally comprised of universities with the highest undergraduate enrollment numbers, while Division II and Division III feature progressively smaller class populations. NCAA, Our Three Divisions, https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2016/1/7/about-resources-media-center-ncaa-101-our-three-divisions.aspx [https://perma.cc/GV3A-SYWL] (last visited Sept. 12, 2022).

In re NCAA Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d at 1062. The conferences included were the Pac-12 Conference, the Big Ten Conference, the Big 12 Conference, Southeastern Conference, the Atlantic Coast Conference, American Athletic Conference, Conference USA, Inc., Mid-American Conference, Mountain West Conference, Sun Belt Conference, and Western Athletic Conference. Id. at 1062, n.1.

Id. at 1091–92. Section 1 of the Sherman Act prohibits “contract[s], combination[s], or conspirac[ies] in restraint of trade or commerce.” 15 U.S.C. § 1.

In re NCAA Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d at 1109.

In re NCAA Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 958 F.3d 1239, 1265–66 (9th Cir. 2020).

NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2147 (2021).

Id. at 2148.

Id. As the Court details, this is in large part due to the non-amateur nature of college sports at the time, as teams operated like commercial enterprises, with athletes moving from school to school to play in big games in return for money.

Id. at 2150–51.

Id. at 2154.

Id. at 2155.

Id. at 2156–57 (“[T]he parties dispute whether and to what extent . . . restrictions in the NCAA’s labor market yield benefits in its consumer market that can be attained using substantially less restrictive means.”).

Id. at 2157.

NCAA v. Bd. of Regents, 468 U.S. 85, 95 (1984).

Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2157. In Board of Regents, the Court noted that “[t]he fact that a practice is not categorically unlawful in all or most of its manifestations certainly does not mean that it is universally lawful.” Bd. of Regents, 468 U.S. at 109 n.39 (quoting P. Areeda, The “Rule of Reason,” in Antitrust Analysis: General Issues 37–38 (Federal Judicial Center, June 1981)).

Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2157.

Id. at 2145, 2160.

Id. at 2160 (citing Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274, 2284 (2019)).

The Court notes that in “nearly all” antitrust cases analyzed under this test over the past forty-five years, plaintiffs failed to meet this burden. Id. at 2160–61.

Id. at 2161. The NCAA argued that its restraints were procompetitive because they promoted amateurism in college sports, therefore keeping consumer demand for the product high. Id.

Id. at 2162. The Court acknowledged a “wrinkle” in the district court’s application of the second prong of the test but found that it did not materially affect the analysis or decision, which ultimately turned on the third prong of the test. Id.

Id. at 2160 (citing Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. at 2284).

Id. at 2162.

Id. at 2160.

Id. at 2163.

Id. (quoting In re NCAA Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058, 1100 (N.D. Cal. 2019)).

Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr LLP, NIL Legislation Tracker, https://www.saul.com/nil-legislation-tracker [https://perma.cc/T6QP-DUSB] (last visited Sept. 11, 2022); see also infra Part IV.

Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2166–67 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

Id. at 2167. Such benefits generally fall under the category of “pay-for-play,” as they solely restrict the compensation student-athletes may receive simply for being a student-athlete. Id.

Id. (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

Id. at 2151 (majority opinion).

Id. at 2167 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

Id. at 2167–68.

Id. at 2167.

Id. at 2167–68.

Id. at 2168.

Id.

Hosick, supra note 4.

Jada Allender, The NIL Era Has Arrived: What the Coming of July 1 Means for the NCAA, Harv. J. Sports & Ent. L. (July 1, 2021), https://harvardjsel.com/2021/07/the-nil-era-has-arrived-what-the-coming-of-july-1-means-for-the-ncaa/ [https://perma.cc/KC5G-78HB].

Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr LLP, supra note 36. In January 2022, Alabama’s legislature voted to repeal its NIL legislation because it was viewed as too restrictive. Brian Lyman, Why State Legislature Is Considering Repeal of NIL Law to Help Alabama, Auburn Recruiting, Montgomery Advertiser (Jan. 14, 2022, 3:00 PM), https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/2022/01/14/alabama-house-considers-repeal-college-athlete-endorsement-nil-law/6529601001/ [https://perma.cc/NYP3-2YEH]. Similarly, other states are considering amending their recently enacted NIL laws. Keller, supra note 5.

Keller, supra note 5. States that have enacted NIL legislation are Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. Id. However, Alabama and South Carolina subsequently repealed its legislation in February and June 2022, respectively. Id. Other states may follow as several are currently seeking to amend or repeal their NIL laws.

Michael McCann, What’s Next After California Signs Game Changer Fair Pay to Play Act into Law?, Sports Illustrated (Sept. 30, 2019), https://www.si.com/college/2019/09/3

0/fair-pay-to-play-act-law-ncaa-california-pac-12 [https://perma.cc/ZCV9-9R9U]. Following the Alston decision, California Governor Newsom “signed a bill that accelerate[d] the timing,” making it effective in September 2021. Colby Bermel, California Accelerates NCAA Athlete Pay Law to Take Effect Wednesday, Politico (Aug. 31, 2021, 10:43 PM), https://www.politico.com/states/california/story/2021/08/31/california-accelerates-ncaa-athlete-pay-law-to-take-effect-wednesday-9427196 [https://perma.cc/95DW-DCC8].James Leonard et al., Name, Image and Likeness Scouting Report, Week 4: The States Quarterback NIL Change, JDSupra (Oct. 11, 2021), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/name-image-and-likeness-scouting-report-2414178/ [https://perma.cc/JK3B-A8PD].

Braly Keller, High School NIL: State-By-State Regulations for Name, Image and Likeness Rights, OpenDorse (Aug. 31, 2022), https://opendorse.com/blog/nil-high-school/ [https://perma.cc/79L9-U7X3]. Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, and Utah appear to expressly permit high school athletes to generate money off their NIL in some manner, with more states considering proposals to do so. Id.

Id.

Id.; see also Tom VanHaaren, QB Quinn Ewers, No. 2 Prospect in 2022, Skipping Senior Season to Join Ohio State, ESPN (Aug. 2, 2021), https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/31942467/source-qb-quinn-ewers-no-2-prospect-2022-skipping-senior-season-join-ohio-state [https://perma.cc/3ARG-5PUX]; Tex. Educ. Code Ann. § 51.9246(j)(1) (West 2021) (“No individual, corporate entity, or other organization may: enter into any arrangement with a prospective student-athlete relating to the prospective student-athlete’s name, image, or likeness prior to their enrollment in an institution of higher education.”).

Keller, supra note 5.

Brendan Menapace, Barstool Sports Has Signed Thousands of College Athletes to NIL Partnerships, But No One (Not Even Barstool) Seems to Know the Plan, Promo Marketing Mag. (Aug. 20, 2021), https://magazine.promomarketing.com/article/barstool-is-trading-branded-merchandise-for-nil-rights-is-it-worth-it-for-athletes/ [https://perma.cc/T9XT-7N8P]. The Barstool Athlete application requires student athletes to simply fill out a short questionnaire, primarily relating to biographical information, and add the phrase “Barstool Athlete” to every social media biography. Although the questionnaire concludes with a disclaimer that Barstool Athletes must “follow all relevant laws and policies relating to the use of [NIL],” which includes not using NIL “to endorse any prohibited conduct, such as gambling, sports betting, drugs, or alcohol,” it remains debatable if this is sufficient to permit student athletes to be endorsed by Barstool (which sponsors each of these prohibited conducts). Barstool Athlete Application, Barstool Sports, https://www.barstoolsports.com/barstool-athlete [https://perma.cc/2AB4-ZCM8] (last visited Sept. 11, 2022).

Ransom Campbell, Louisville Tells Student-Athletes to Cease NIL Involvement with Barstool Sports, Talking Points Sports (Aug. 11, 2021), https://talkingpointssports.com/college-football/college-sports/louisville-tells-student-athletes-to-cease-nil-involvement-with-barstool-sports/ [https://perma.cc/V73F-LA3N] (“[T]here has been consistent speculation surrounding the implications of student-athletes agreeing to the Barstool Sports official collegiate athlete program, Barstool Athletics.”). As discussed in Part IV of this Note, the NCAA is currently investigating several schools for potential NIL violations. See infra Part IV. However, the NCAA does not appear to have investigated or punished any student-athletes for NIL violations so far.

Brinley Chabot, What Do Barstool Athletes Actually Get from the Sponsorship?, CenterField (Nov. 24, 2021), https://centerfieldmarist.com/2021/11/24/what-do-barstool-athletes-actually-get-from-the-sponsorship/ [https://perma.cc/2BNK-6M7Z].

For example, Georgia allows team contracts to pool athletes’ NIL earnings. Madeline Coleman, Georgia NIL Law Would Allow Schools to Pool, Redistribute Athletes’ Endorsement Money, Sports Illustrated (May 6, 2021), https://www.si.com/college/2021/05/06/georgia-kemp-signs-name-image-and-likeness-bill-pool-resditribution-law [https://perma.cc/U6MD-YT3H].

Cole Thompson, TAMU’s Ainias Smith Pledges to Give Percentage of NIL Money to Teammates, Sports Illustrated (July 2, 2021), https://www.si.com/college/tamu/football/tamus-ainias-smith-pledges-to-give-percentage-of-nil-money-to-teammates [https://perma.cc/2QZ6-33XP]; Chip Towers, Georgia QB JT Daniels Including Teammates on NIL Deals, Atlanta J.-Const. (Aug. 17, 2021), https://www.ajc.com/sports/georgia-bulldogs/georgia-qb-jt-daniels-including-teammates-on-nil-deals/N4YGH4J5SZGSRKJLUNW5CGMCVY/ [https://perma.cc/J397-82HP].

Towers, supra note 61. Although Daniels was viewed as a preseason Heisman contender, he lost the starting job to Stetson Bennett IV following a series of injuries. Harrison Reno, REACTION: Stetson Bennett Returns, Daniels Departs, Dawgs Daily (Jan. 19, 2022), https://www.si.com/college/georgia/news/reaction-stetson-bennett-returns-daniels-departs [https://perma.cc/7FUZ-7GMQ]. After Bennett led Georgia to its first National Championship in over forty years, Daniels entered the transfer portal in January 2022. Seth Emerson, Georgia QB JT Daniels Enters Transfer Portal, Stetson Bennett Announces His Return, Athletic (Jan. 17, 2022), https://theathletic.com/news/georgia-qb-jt-daniels-enters-transfer-portal-stetson-bennett-announces-his-return/SOb4288ci90A/ [https://perma.cc/2FLQ-YJJR]; Harrison Reno, Georgia Fans Break Records Following National Championship Win, Dawgs Daily (Jan. 18, 2022, 7:22 PM), https://www.si.com/college/georgia/news/georgia-fans-breaking-records-following-national-championship-win [https://perma.cc/EH6J-T39M].

Towers, supra note 61.

Id. Part of Daniels’s arrangement with Zaxby’s included having Zaxby’s donate meals to “Extra Special People (ESP), a Georgia-based non-profit that supports and empowers young people with disabilities.” Johnathan Tillman, Georgia’s JT Daniels: The NIL Era’s Ultimate Good Guy, Boardroom (Sept. 3, 2021), https://boardroom.tv/georgia-jt-daniels-nil-deals/ [https://perma.cc/JLK7-9UBC]; see also Andrew Gastelum, Michigan RB Uses NIL Money to Buy Thanksgiving Turkeys for Families in Need, Sports Illustrated (Nov. 22, 2021), https://www.si.com/college/2021/11/22/blake-corum-nil-money-distribute-thanksgiving-turkeys-michigan [https://perma.cc/4TYD-R76V].

Illinois NIL for NCAA, Spry (Aug. 22, 2022), https://spry.so/nil-state-guide/illinois-nil-law-for-ncaa/ [https://perma.cc/NN54-XJPK]; Mississippi NIL for NCAA, Spry (Aug. 22, 2022), https://spry.so/nil-state-guide/mississippi-nil-law-for-ncaa/ [https://perma.cc/U8ET-2JWZ]; Texas NIL for NCAA, Spry (Aug. 22, 2022), https://spry.so/nil-state-guide/texas-nil-law-for-ncaa/ [https://perma.cc/M9WQ-PV69].

Dennis Dodd, Spencer Rattler Becomes Case Study for NIL Return on Investment with Oklahoma Starting Job in Flux, CBS Sports (Oct. 13, 2021, 3:41 PM), https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/spencer-rattler-becomes-case-study-for-nil-return-on-investment-with-oklahoma-starting-job-in-flux/ [https://perma.cc/WYT7-FZQF] (quoting Blake Lawrence, CEO of technology-based social media giant Opendorse: “Competing schools might clearly say in the recruiting process, ‘Hey, we will give you a platform to speak’”).

About the NCPA Protecting Future, Current, and Former College Athletes, Nat’l Coll. Players Ass’n, https://www.ncpanow.org/about-us [https://perma.cc/ZE8W-YNNN] (last visited Sept. 12, 2022).

Liz Clarke, State-by-State Rating System Gives College Recruits Road Map to Evaluate NIL Laws, Wash. Post (Oct. 21, 2021, 12:34 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2021/10/21/name-image-likeness-laws-state-rankings/ [https://perma.cc/49NN-DGV3].

The NCPA’s Official NIL Ratings, Symposium, https://symposium.us/ncpa-nil-ratings/ [https://perma.cc/3WSG-DARP] (last visited Sep. 29, 2022) [hereinafter NCPA Rankings] (Note: to access the article, enter your first and last name, email address, and whether you are a “Recruit,” “Transfer,” or “Other.”).

Id.

Id.; Allen Grove, Southeastern Conference–NCAA Division I Athletics, ThoughtCo (July 30, 2020), https://www.thoughtco.com/universities-in-southeastern-conference-787012 [https://perma.cc/3TG9-QHG5]. Note that this includes Alabama, although the state recently repealed its NIL legislation. William Lawrence, Alabama Has Repealed Its NIL Law–Can Alabama’s Student-Athletes Still Get Paid?, ThoughtCo (Feb. 17, 2022), https://www.thoughtco.com/universities-in-southeastern-conference-787012 [https://perma.cc/TLC7-FPXA].

Lyman, supra note 49.

NCPA Publishes State NIL Law Ratings for Recruits, NCPA Coll. Players (Oct. 21, 2021), https://www.ncpanow.org/releases-advisories/ncpa-publishes-state-nil-law-ratings-for-recruits [https://perma.cc/S88D-AEWE].

Hosick, supra note 4.

Dan Murphy, BYU Cougars Sponsor Offers to Cover Tuition for Walk-On Members of Football Team, ESPN (Aug. 12, 2021), https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/32010626/byu-cougars-sponsor-offers-cover-tuition-walk-members-football-team [https://perma.cc/X75H-T6PS].

IU Athletics Unveils First-of-Its-Kind NIL Directory, IUHoosiers (Aug. 6, 2021, 2:50 PM), https://iuhoosiers.com/news/2021/8/6/name-image-likeness-iu-athletics-unveils-first-of-its-kind-nil-directory [https://perma.cc/U9MU-5EWH].

NCPA Rankings, supra note 69. “[I]nstitutions are generally prohibited from being involved in the specifics of their student-athletes’ NIL activities, and for a variety of good reason: too much institutional involvement can lead to claims for contractual non-performance, as well as campus compliance, Title IX and a host of employment-related issues.” Erin Butcher & Jeff Knight, College-Wide and Team-Specific NIL Deals: Considerations for Colleges and Universities to Avoid Unwanted Consequences, JDSupra (Sept. 22, 2021), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/college-wide-and-team-specific-nil-6646801/ [https://perma.cc/685N-8Q4D].

Drew Davison, ‘There Is No Wrong.’ TCU’s Patterson Delivers NIL Message to Local Business Leaders, Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Sept. 16, 2021, 8:51 AM), https://www.star-telegram.com/sports/college/big-12/texas-christian-university/article254278183.html [https://perma.cc/W3WS-RAN4].

One such reward story is Jared Casey’s, a walk-on tight end for the University of Kansas football team who “caught the game-winning two-point conversion” in overtime against the University of Texas. Chris Bengel, Kansas Walk-On Jared Casey Lands NIL Deal with Applebee’s Following Game-Winning Play vs. Texas, CBS Sports (Nov. 19, 2021, 11:50 AM), https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/kansas-walk-on-jared-casey-lands-nil-deal-with-applebees-following-game-winning-play-vs-texas/ [https://perma.cc/47W6-6LRV]. Following the game, Applebee’s and Casey entered into an NIL deal that involved Casey starring in commercials for the restaurant chain in exchange for cash and Applebee’s gift cards. Id.

Murphy, supra note 75; see also Wilton Jackson, BYU Football Strikes NIL Deal to Pay Tuition for Walk-On Players, Sports Illustrated (Aug. 12, 2021), https://www.si.com/college/2021/08/12/byu-football-nil-deal-walk-on-tuition-built-bar [https://perma.cc/3DWD-RZL7]. BYU negotiated a multi-year deal with Built Brands, a protein and energy product company, “that will include compensation to all 123 members of the Cougars’ football team as well as provide full tuition for walk-on players.” Id.

Murphy, supra note 75. Players received silk pajamas, prepaid debit cards, and TiVo’s 4k streaming device in exchange for promoting TiVo on social media. Id.

Id.

Butcher & Knight, supra note 77.

Id.

Associated Press, Nonprofit to Offer Texas Offensive Linemen $50,000 Annually, Sports Illustrated (Dec. 6, 2021), https://www.si.com/college/2021/12/07/texas-offensive-line-nil-deal-nonprofit [https://perma.cc/DQR6-DKYF].

Amanda Christovich, Player-Led Collectives Could Be the Newest NIL Trend, Front Off. Sports (June 9, 2022, 1:40 PM), https://frontofficesports.com/player-led-collectives-could-be-the-newest-nil-trend/ [https://perma.cc/EU5M-C8FB].

Id.; Pete Nakos, Michigan State Player-Driven NIL Collective Setting New Trend, ON3 (June 9, 2022), https://www.on3.com/nil/news/michan-statefootball-east-lansing-players-club-collective-auburn-football-the-plains-nil-name-imagelikeness/ [https://perma.cc/VS56-7GXN].

Ross Dellenger, Wild Red River Showdown Sets Up Fascinating NIL Impact for Spencer Rattler, Caleb Williams, Sports Illustrated (Oct. 9, 2021), https://www.si.com/college/2021/10/09/oklahoma-texas-spencer-rattler-benched-caleb-williams-nil [https://perma.cc/72H4-82HZ]; see also Tim Daniels, Spencer Rattler to Transfer to South Carolina After 3 Seasons at Oklahoma, Bleacher Rep. (Dec. 13, 2021), https://bleacherreport.com/articles/10019778-spencer-rattler-to-transfer-to-south-carolina-after-3-seasons-at-oklahoma [https://perma.cc/J5TX-CESL].

See Dellenger, supra note 88.

Ross Dellenger, College Football, Meet Caleb Williams: ‘He Saves the Day,’ Sports Illustrated (Oct. 15, 2021), https://www.si.com/college/2021/10/15/caleb-williams-oklahoma-football-daily-cover [https://perma.cc/3RVP-RHCK] (“But the question, Cavale says, isn’t what happens to Rattler—it’s what happens to Williams?”).

See Dodd, supra note 66 (“What Fowler is essentially saying is the car deal is in itself a recruiting pitch for the next great Oklahoma quarterback.”).

Caleb Williams (@CALEBcsw), Twitter (Jan. 3, 2022, 3:05 PM), https://twitter.com/CALEBcsw/status/1478110195205165059 [https://perma.cc/QDH7-B32A]; Oklahoma QB Caleb Williams Enters Transfer Portal, Fox Sports (Jan. 4, 2022), https://www.foxsports.com/stories/collegefootball/oklahoma-qb-caleb-williams-enters-transfer-portal [https://perma.cc/6JPC-V7FW].

“We have free agency in college football. The kids, a lot of times, go to where they get paid the most.” Scott Polacek, Texas A&M HC Jimbo Fisher Says NIL Deals Happened in Past: ‘They Just Weren’t Legal,’ Bleacher Rep. (Dec. 15, 2021), https://bleacherreport.com/articles/10020979-texas-am-hc-jimbo-fisher-says-nil-deals-happened-in-past-they-just-werent-legal [https://perma.cc/R84A-79P4] (quoting Ole Miss head coach, Lane Kiffin); Ross Dellenger, Caleb Williams Lands with New Team, but His Larger Goal Remains the Same, Sports Illustrated (Feb. 17, 2022), https://www.si.com/college/2022/02/17/caleb-williams-usc-new-team-nfl-draft [https://perma.cc/GD2V-XQ5N]; Evan Desai, OU Continues to Spiral After USC Football HC Lincoln Riley’s Departure, Reign of Troy (Oct. 2, 2022), https://reignoftroy.com/posts/ou-continuesspiral-after-usc-football-hc-lincoln-riley-departure [https://perma.cc/8TFE-PHBU]. Williams and his family insist that “NFL, not NIL [was] the guiding light of [Williams’ decision].” Wilton Jackson, Caleb Williams’s Reported Transfer Timetable Offers Little Clarity, Sports Illustrated (Jan. 19, 2022), https://www.si.com/college/2022/01/19/former-oklahoma-quarterback-caleb-williams-shares-transfer-timetable [https://perma.cc/G86E-WTVG]. However, in a sport where an injury can cause a drop down the NFL draft boards (and a correlative loss in rookie salary), it is probably fair to speculate that Williams’s decision was due to a combination of wanting to be best prepared for the NFL but also taking advantage of his value now, while he still can.

Anthony Farris, Caleb Williams Has a Million Reasons to Play for Eastern Michigan, Fox News (Jan. 6, 2022, 1:09 PM), https://www.foxnews.com/sports/caleb-williams-million-reasons-play-eastern-michigan [https://perma.cc/D4B4-EZME].

One of quarterback Quinn Ewers’s endorsement deals in Ohio was with a local car dealership, which provided Ewers with a three-year lease on a 2020 Ford F-250 truck. Christian Red, Ohio State Quarterback Quinn Ewers Didn’t Waste Time Chasing Name, Image and Likeness Deals, Forbes (Oct. 19, 2021, 4:17 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/christianred/2021/10/19/ohio-state-quarterback-quinn-ewers-didnt-waste-time-chasing-name-image-and-likeness-deals/?sh=6ec514bc216e [https://perma.cc/366N-JXE5]. Upon entering the transfer portal, the lease (and associated endorsement deal) reportedly ended. Rick Ricart (@RickRicart), Twitter (Dec. 10, 2021, 10:53 AM), https://twitter.com/RickRicart/status/1469349618379104266?s=20 [https://perma.cc/4FVU-N5XZ].

See supra note 55 and accompanying text.

See supra note 55 and accompanying text.

Tom VanHaaren, Ohio State Buckeyes QB Quinn Ewers Has NIL Deal for $1.4 Million, Source Says, ESPN (Aug. 31, 2021), https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/32120440/ohio-state-buckeyes-qb-quinn-ewers-nil-deal-14-million-source-says [https://perma.cc/3PX6-9HS5]; Jake Aferiat, Why Former Top QB Commit Quinn Ewers Reportedly Intends to Transfer from Ohio State, Possible Landing Spots, Sporting News (Dec. 3, 2021), https://www.sportingnews.com/us/ncaa-football/news/quinn-ewers-transfer-ohio-state-landing-spots/11004vyb20pyf1efi67w7v0p9k [https://perma.cc/FH98-BTDX].

Tom VanHaaren, Former 5-Star Recruit Quinn Ewers Will Join Texas Football as Transfer QB, Have Four Years of Eligibility, ESPN (Dec. 12, 2021), https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/32856030/former-5-star-recruit-quinn-ewers-join-texas-football-transfer-qb-four-years-eligibility [https://perma.cc/FUP9-5AB5]; Aferiat, supra note 98.

Geoff Ketchum (@gkketch), Twitter (Dec. 7, 2021, 10:07 AM), https://twitter.com/gkketch/status/1468250938192404490?s=20 [https://perma.cc/P3PR-FMUW]; see also Tyler Sullivan & Jordan Dajani, NFL First-Round Draft Picks Contract Tracker: Steelers Sign Kenny Pickett as Every Round 1 Pick Under Contract, CBS Sports (June 1, 2022, 10:32 AM), https://www.cbssports.com/nfl/news/nfl-first-round-draft-picks-contract-tracker-steelers-sign-kenny-pickett-as-every-round-1-pick-under-contract/ [https://perma.cc/E4P9-GMSY]. Geoff Ketchum is the owner and publisher of Orangebloods.com, a University of Texas athletics insider website. Jason Suchomel, About Us, Orangebloods (July 14, 2010), https://texas.rivals.com/news/about-us-50 [https://perma.cc/5EXX-YARN].

The use of the transfer portal in this manner also coincided with the NCAA passing a 2021 rule allowing first-time transferees to obtain immediate eligibility at their new schools. NCAA Division I One-Time Transfer FAQS, NCAA, http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/eligibility_center/Transfer/OneTime_Transfer.pdf [https://perma.cc/A5FV-R7MA] (Sept. 2022). At the time of this writing, the NCAA is considering relaxing transfer restrictions even further and allowing athletes to transfer an unlimited number of times while retaining immediate eligibility to play. Michelle Brutlag Hosick, DI Council Endorses Transformation Committee Concepts, NCAA (July 20, 2022, 7:30 PM), https://www.ncaa.org/news/2022/7/20/media-center-di-council-endorses-transformation-committee-concepts.aspx [https://perma.cc/78SC-8WDC].

See supra Section III.B.

Johnson v. NCAA, 556 F. Supp. 3d 491, 497–98 (E.D. Pa. 2021).

15-Year Trends in Division I Athletics Finances, NCAA, https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Finances/2020RES_D1-RevExp_Report.pdf [https://perma.cc/57QC-RUJD] (last visited Sept. 18, 2022).

Id.

As the Alston court indicated, however, this may ultimately not be a huge loss given the NCAA’s inability to explain its conception of amateurism in a consistent manner. See supra Section II.A. This Note does not explore the possible ramifications of striking down the NCAA’s amateurism model.

2009–10 NCAA Div. I Manual: NCAA Const. art. 1.3.1 (NCAA 2009).

See supra Part II.

Early indications from INFLCR, a software company that provides an NIL marketplace to connect businesses with athletes, are that the median NIL transaction is a mere $63. Zach Barnett, NIL Data: Median Transaction Goes for Less than $63, Footballscoop (Nov. 15, 2021), https://footballscoop.com/news/nil-data-median-transaction-63-dollars [https://perma.cc/7BQC-LVW6]; see also Dan Whateley & Colin Salao, How College Athletes Are Getting Paid from Brand Sponsorships as NIL Marketing Takes Off, Insider (Sept. 7, 2022, 1:29 PM), https://www.businessinsider.com/how-college-athletes-are-getting-paid-from-nil-endorsement-deals-2021-12 [https://perma.cc/8ENF-FB3F].

Johnson v. NCAA, No. 19-5230, 2021 WL 6125095, at *1 (E.D. Pa. Dec. 28, 2021).

Id. at *3–4.

Tatianna Witter, From “Student-Athletes” to “Players”: A Review of the 2021 Legal Developments Shaping a New Reality of College Sports, JDSupra (Jan. 6, 2022), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/from-student-athletes-to-players-a-6189761/ [https://perma.cc/QKW6-8B3J].

NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2166–67 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

Id. at 2168 (“And . . . it is not clear how the NCAA can legally defend its remaining compensation rules.”).

Id. at 2159–60 (majority opinion) (“The NCAA is free to argue that, ‘because of the special characteristics of [its] particular industry,’ it should be exempt from the usual operation of the antitrust laws—but that appeal is ‘properly addressed to Congress.’” (quoting Nat’l Soc. Prof. Eng’r v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 689 (1978))).

Clarke, supra note 68.

Corbin McGuire, NCAA Members Approve New Constitution, NCAA (Jan. 20, 2022, 6:12 PM), https://www.ncaa.org/news/2022/1/20/media-center-ncaa-members-approve-new-constitution.aspx [https://perma.cc/V9M8-7VAK].

Daniel Libit & Eben Novy-Williams, NCAA Probes BYU, Miami NIL Deals for Potential Pay-For-Play Violation, Sportico (Dec. 10, 2021, 4:46 PM), https://www.sportico.com/leagues/college-sports/2021/ncaa-byu-miami-nil-probe-1234650215/ [https://perma.cc/4D6H-U5VQ].

“The BYU and Miami deals have been viewed by others in the compliance space as NCAA gut checks, effectively daring the weakened and besieged governing body to take an increasingly unpopular—and, perhaps, illegally anticompetitive—stand against athletes earning money while they play.” Id.

The new constitution recently approved by the NCAA shifts responsibility for NIL standards and regulations to its three divisions. NCAA Const. arts. I(A)(d)(ii), II(B)(1), III(A) (Dec. 14, 2021, approved Jan. 20, 2022), available at https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/governance/ncaa/constitution/NCAAGov_Constitution121421.pdf [https://perma.cc/49BN-HY8J]. Therefore, there is a possibility that issues among schools in the same conferences may be resolved depending on the action taken by each division.

Andrew Bondarowicz, Alabama Repeals State NIL Law Less than a Year After Passage, Sports Litig. Alert (Apr. 22, 2022) https://sportslitigationalert.com/alabama-repeals-state-nil-law-less-than-a-year-after-passage/ [https://perma.cc/3RW8-QBLZ].

This Note does not go so far as to explore whether such a cap should be implemented.

Amanda Christovich, Constitutional Convention’s Timeline, Front Off. Sports (Oct. 15, 2021, 10:53 AM), https://frontofficesports.com/constitutional-conventions-timeline/ [https://perma.cc/P8LR-DJP3].

McGuire, supra note 117.

Id.

NCAA Const., art. II, § B(4), supra note 120.

Meghan Durham, NCAA Board of Governors to Convene Constitutional Convention, NCAA (July 30, 2021), https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/news/general-ncaa-board-of-governors-to-convene-constitutional-convention [https://perma.cc/7KL3-UL48].

Desha Jackson & Victoria Nguyen, It’s All About the Benjamins: College Athletes Getting Paid for Their Name, Image, and Likeness, 328 N.J. Law. 24, 26 (2021).

Id.

Id.

Amanda Christovich, The Current Group Licensing Reality in the NCAA, Front Off. Sports (Oct. 4, 2021, 12:14 PM), https://frontofficesports.com/the-current-group-licensing-reality-in-the-ncaa/ [https://perma.cc/KN77-CTVB]. In addition to Ohio State, The Brandr Group has agreements with the University of North Carolina, the University of Texas, the University of Alabama, Appalachian State, Indiana University, Michigan State University, the University of Florida, North Carolina State, Villanova University, the University of Nebraska, the University of Maryland, Marquette University, Oklahoma State University, Texas Tech University, Xavier University, Purdue University, and the University of Georgia. The Brandr Group, https://www.thebrandrgroup.com/ [https://perma.cc/VVX9-ULE6] (last visited Sept. 18, 2021).

Christovich, supra note 131.

Aaron Beard, Group Licensing: A New Way for College Athletes to Cash In, AP News (July 20, 2021), https://apnews.com/article/sports-business-mens-college-basketball-college-basketball-north-carolina-tar-heels-mens-basketball-cd644a8660fa9ffc659970ebe6e5fa75 [https://perma.cc/2JLJ-NX83] (discussing how group licensing deals allow college athletes and universities to commercialize their respective names).