I. Introduction

It is common practice for lawyers, judges, and scholars to study the universe of adjudicated infringement cases to identify threads that are then woven into “the law.” Sometimes these inspections are close-up with a magnifying glass; other times they study the entire landscape as if from a hot-air balloon. P.J. Federico’s 1956 article Adjudicated Patents provides an early example of the latter in the context of patent law. Federico’s article provided new insights into the number of patents adjudicated in both the district and appellate courts over a seven-year period from 1948 to 1954 through the use of careful and systematic case coding.[1] Since the 1950s, dozens of scholars have conducted their own studies of patent infringement litigation, applying a range of quantitative methodologies from frequentist statistics to graphical depictions to regressions and more.[2]

Yet, appeals are not randomly chosen by a roll of the dice. Instead, as George Priest observed over four decades ago, the decision of parties to settle or litigate affects the substance of judicial decision-making.[3] Surprisingly, then, while there is substantial published empirical research on district court and Federal Circuit decisions separately, there is comparatively little empirical work that examines what happens between these layers. A major barrier is the lack of a publicly accessible dataset linking district court cases to Federal Circuit decisions. Consequently, the current approach is to manually research each of thousands of district court cases filed each year to determine if it was the subject of an appellate decision, a task that researchers must repeat anew again and again.

This Article closes that gap through the construction of a multilayered relational dataset of patent infringement cases from filing to appeal to appellate decision. We use this data to assess hypotheses about different types of patent asserters and what happens in appeals of those cases.

While there are a variety of different lenses through which we could view the relationship between patent infringement cases in the district courts and on appeal, we situate this Article within the ongoing debates around companies that acquire patents but do not themselves practice the claimed technologies. The purpose of this Article is not to take a normative position on whether these “Patent Assertion Entities” (PAEs) are socially beneficial or harmful, but rather to contribute new information to the debate relating to their litigation behavior and outcomes. In doing so, we explore questions such as: “how do different types of patent asserters compare in their frequency of appeal?”; “do some litigant types settle more frequently during the appeal process?”; and ultimately, “do PAEs fare better or worse on appeal than product companies?”

We find that, for some aspects of appeals, such as whether there was an appeal in a patent infringement case, cases brought by PAEs look similar on appeal to cases brought by product companies. But we also observe some substantial differences among litigant types—in particular, whether cases filed by PAEs are appealed more often and who is filing the appeals in those cases. We also observe a story in the background: regardless of the patent asserter type, most appeals are filed by patent owners, not accused infringers. Furthermore, even accounting for this difference, accused infringers are more successful on appeal than patent asserters—again, regardless of the type of patent asserter.

The methodology and code that we employ in this Article to match district court cases to Federal Circuit appeals can be easily adapted to other datasets. For example, we have employed a similar methodology to link the Stanford Non-Practicing Entity (NPE) Litigation Database to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) Patent Litigation Dataset,[4] as well as the USPTO dataset to our dataset of Federal Circuit decisions. In addition, we have employed this methodology to link the data from a recent study by Chris Cotropia, Jay Kesan, and David Schwartz to the Federal Circuit data.[5] All of the data and code used in this project will be publicly archived and made freely available for future research.[6]

This Article is organized as follows. In Part II, we provide a brief background on past empirical studies of patent litigation at the district court and appellate levels. Part III describes the methodology for constructing the multilayered relationships between infringement actions, appeals, and appellate decisions, as well as foundational statistics about the frequency of appeal. In Part IV, we present findings from the relational datasets to answer the question of who appeals patent infringement cases (and what happens). Finally, in Part V we offer analysis of our findings.

II. Background

A central topic of discussions about the patent system for the past two decades has been the role and behaviors of patent owners that do not themselves practice the technology claimed in the patents.[7] Although initially described simply as “patent trolls” or “non-practicing entities,”[8] more recent scholarship has described an entire ecosystem of different patent owners who obtain patents without practicing the claimed technology.[9]

The conventional anti-troll narrative revolves around companies that acquire patents of questionable validity and then use the threat of litigation to extract nuisance cost settlements from hardworking companies that actually produce goods or provide services.[10] The opposing narrative contends that these entities serve a range of socially beneficial functions: they create markets for patents that support investment in start-up companies; help level the playing field for small companies against established, well-capitalized competitors; and provide a way for inventors to monetize their inventions without themselves making a product or providing a service.[11]

Yet, as scholars such as Colleen Chien and others have recognized, both narratives are overly simplistic: there are a variety of different types of entities that assert patents even though they don’t themselves practice the technology.[12] Non-practicing patent owners exhibit substantial heterogeneity, ranging from individual inventors to universities to failed startups to large patent aggregators, each with their own behavioral patterns in litigation.[13] Scholars have studied whether various claims are true about these entities[14] and have explored their behavior during litigation—especially at the district court level.[15]

Recently, scholars have begun to use quantitative methodologies to examine the behavior of these entities. This research is possible because, while the population of patent infringement lawsuits is large, it is relatively well-defined. Patent infringement lawsuits are heard almost exclusively in the federal district courts,[16] while appeals in patent infringement cases are heard exclusively by the federal appellate courts—and since 1982, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.[17] In addition, because almost all appeals are heard as of right, rather than at the Federal Circuit’s discretion, the court itself does not exercise selection over which appeals it decides; rather, all appellants who satisfy the appellate jurisdiction criteria are entitled to a decision by the court.[18] These procedural facets of patent litigation make it possible to identify and study these cases by focusing exclusively on the federal court system and narrow the possible appellate courts to just one.

One important example is the analysis conducted by Michael Risch, one of the pioneers of empirical research on PAE litigation, who examined litigation outcomes over a several decades period of time by comparing infringement cases filed by the ten most litigious NPEs of the 2000s to a loosely matched control set of about the same number of cases filed by other entities over the period 1986–2009.[19] Risch found that the patents asserted by the ten most litigious NPEs in the study were found invalid and noninfringed about twice as often as the comparable non-NPEs but that the vast majority of patents in both cases were never litigated to a decision.[20]

Another example is the work by John Allison, Mark Lemley, and David Schwartz. Drawing on a set of all patent lawsuits filed in federal district courts between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2009, they systematically examined the merits outcomes for infringement lawsuits brought by different categories of litigants.[21] They found that for lawsuits filed in those years, operating companies brought nearly three-quarters of the suits while the remainder were composed of different types of entities that the authors classified as NPEs—including individuals, universities, failed startups, and PAEs.[22] Overall, patent asserters won about a quarter of their cases that went to a final judgment, but win rates were different for different entity types.[23] Operating companies and universities each won about 30% of the cases that went to final decision, failed startups 21%, individuals 15%, and PAEs around 10%.[24]

Another example is the work of Chris Cotropia, Jay Kesan, and David Schwartz, who conducted two studies of infringement cases filed in 2010 and 2012.[25] Cotropia et al. observed a wide range of different case characteristics for different categories of patent asserters, suggesting the importance of separately examining different types of patent asserters.[26] They also found that the sharp increase in the number of lawsuits between 2010 and 2012 was the result of a change in the law restricting the circumstances in which defendant joinder is permissible, rather than an “explosion” of PAE-initiated cases.[27] Their studies were subsequently followed by the work of Kesan, Layne-Farrar, and Schwartz expanding the set of district court cases to encompass 2011 and 2013 to examine so-called patent privateers.[28]

Contemporaneously, Shawn Miller’s research team at Stanford developed the “Stanford NPE Litigation Database,” a publicly available dataset of the entities asserting patents in litigation containing data for nearly all patent infringement cases filed since 2000.[29] The Stanford NPE Litigation Database continues to be actively maintained and is the dataset of district court cases that we use in this project.[30] Using the Stanford dataset, Miller et al. found that between 2006 and 2015, there was “a marked decrease in the share of all patent litigation attributable to practicing entities.”[31] “Prior to 2006, about 70% of all lawsuits and 60% of all defendant-lawsuit pairs asserted practicing-entity patents”; between 2006 and 2015, “those two percentages have dropped to around 45% each.”[32] Miller et al. also observed that cases filed by companies that acquired patents settled more frequently and had a lower win rate in merits decisions at the district courts.[33]

A limitation of the existing studies on patent asserter types is that they examine only a specific subset of patent infringement litigation, such as cases filed in the district courts,[34] or are limited to a particular cohort of cases (such as the patent litigations asserted by the top ten most litigious NPEs for the 2000s and a comparison set of loosely matched cases).[35] This is typical of studies of patent litigation generally: these studies tend to focus on a particular component of the entire system, such as just patent infringement cases at the district courts or just patent appeals at the Federal Circuit,[36] cases filed in a particular year or two,[37] or cases addressing a particular issue such as the doctrine of nonobviousness.[38]

One reason why the existing research is limited to these subsets is the difficulty of collecting the data and then matching large numbers of district court cases to appellate decisions. Allison, Lemley, and Schwartz’s study of outcomes of patent infringement lawsuits filed in 2008 and 2009 provides an example.[39] Allison, Lemley, and Schwartz followed a cohort of cases from filing to final disposition, whether at the district court or the Federal Circuit.[40] Of the approximately 5,000 patent infringement lawsuits filed in 2008 and 2009, they found 949 merits decisions on patents made in 462 different district court cases.[41] Of those 949 merits decisions, 273 resulted in a Federal Circuit decision on appeal, with another 82 pending at the time the article was written.[42] To obtain this information, however, required a tremendous amount of time-intensive hand coding by the authors of the study, including careful review of the dockets and individual matching to an appeal.[43] This imposes a substantial barrier to large-scale studies that involve both district court cases and appeals.

While commercial platforms such as Westlaw and LexisNexis may have data on these appeals, the databases maintained by these entities are proprietary, with contractual restrictions and user interfaces that are fundamentally at odds with transparency and open access to data.[44] Instead, what is needed is a way to easily connect to existing open-access data sources of district court cases and Federal Circuit appeals that can be applied to large numbers of cases.

III. Methodology for Linking the Data

This Article examines the relationship between patent infringement cases filed in the district courts and Federal Circuit appellate decisions arising from those cases. Because there was no existing publicly accessible dataset combining district court patent infringement cases and Federal Circuit appellate decisions, we first needed to construct a relational data structure containing both district court and Federal Circuit decisions. A relational model is a data structure involving multiple data tables that relate to one another.[45] In other words, rather than employing a single flat table with rows and columns (e.g., think an Excel worksheet), the data takes the form of multiple tables that relate to each other through data that is common across tables.

This part describes the basic methodology for constructing the relationships between the datasets and some descriptive observations about Federal Circuit appeals from district courts generally. Additional methodological detail on the construction of the relational database structure is provided in Studying Patent Infringement Litigation.[46]

A. Datasets

Data for the trial court layer—patent infringement cases at the district courts—comes from the Stanford NPE Litigation Database. Data for the appellate court layer comes from the Federal Circuit Dataset Project.

As described above, the Stanford NPE Litigation Database contains information on the nature of parties that file patent infringement lawsuits. For the period from 2000 to 2021, the Stanford dataset contains 76,372 total actions filed in federal district courts.[47] Records are unique with respect to federal district (e.g., the Northern District of Iowa) and civil action number.[48] Miller et al. used a team of student coders to categorize the district court actions into distinct patent asserter categories.[49] Patent asserters were categorized into distinct buckets based on their past actions or entity/inventor type.[50] The key categories from the Stanford dataset used by this Article are Categories 1, 5, 6, 8, and 9.[51]

Category 1 asserters are those who acquired the patent after the patent was originally held by a different entity; this category explicitly does not include asserters that “made, sold, or offered a product or service.”[52]

Category 5 asserters are companies that are led by the individual inventor of the patent and mostly consist of limited liability companies (LLCs) where the original inventor is a member.[53]

Category 6 asserters are any government, nonprofit, or university entity.[54]

Category 8 asserters are companies in the business of creating new products, whatever the product industry.[55] This category also includes companies that only offer services (if not related to patent enforcement) and do not produce tangible goods.[56]

Category 9 asserters are those that litigate in their own individual name and not as an LLC or other corporate entity.[57]

Data for the appellate layer comes from the Federal Circuit Dataset Project, which contains a dataset of all appeals filed at the Federal Circuit (the appeal docket dataset) and a dataset of all opinions and Rule 36 summary affirmances since 2007 (the appeal document dataset). At the time of our analysis, the dataset contained all dockets and appellate decisions through December 31, 2021. The document dataset contains information about a wide array of decision attributes, including document type, panel judges, date of decision, opinion authors, outcomes, patent numbers, dispute type, appellant type, and more.[58] Because the focus of this study is on appeals as of right, we excluded dockets for petitions for writs of mandamus and permission to appeal.[59]

One limitation of the appeal docket dataset is that there is more limited information for appeals filed before 2011.[60] Many of these older records are only contained in a legacy PACER system that provides limited information on the forum in which the case originated.[61] As a result, the set of appellate dockets was restricted to only appeals filed in 2011 or later so that we could draw on the PACER-provided data. In addition, we limited the appeal docket dataset to only appeals arising from the district courts. In total, the appeal docket dataset contained 4,840 unique dockets for appeals arising from the district courts and filed at the Federal Circuit between 2011 and 2021.

To summarize, the Stanford dataset contains data on patent infringement cases in the district courts, while the Federal Circuit dataset project contains data on all appeals at the Federal Circuit, as well as all outcomes that resulted in an opinion or Rule 36 summary affirmance.

B. Linking the Datasets

A challenge in linking the district court and appellate datasets is that there is often a many-to-many relationship between cases, appeals, and decisions. This means that a single civil action in the district court may be appealed multiple times, and a single appellate decision might resolve multiple appeals (and thus multiple district court civil actions).[62]

We addressed this complexity using several techniques. First, we defined the record units for each dataset. At the district court, the record unit is an individual district court docket, i.e., civil action (in the diagram below, these are District Court Docket 1 and District Court Docket 2). At the appellate level, there are two record units: appeals and decisions. An appeal is identified by its docket number (as shown in the diagram below, Appeal Docket 1, Appeal Docket 2, etc.), while appellate decisions take the form of a specific document containing that decision (in the diagram below, CAFC Decision 1 and CAFC Decision 2). While a single civil action at the district court can be associated with more than one appeal, each appeal docket is associated with only one civil action (in the diagram below, the second district court docket is linked to two appeals, but none of the appeals are linked to more than one civil action). Finally, at the appellate decision level, we limit the analysis to the final panel decision. Thus, for instances in which an opinion or terminating order has been replaced by a newer document by the court, we treat the newer document as the decision of record.[63] Consequently, each docketed appeal has only a single terminating opinion or order. (In the diagram below, CAFC Decision 1 decides both Appeal Docket 1 and Appeal Docket 2, but none of the Appeal Dockets are linked to more than one decision.)

The following diagram illustrates the relationship:

Second, our primary approach employs the first appeal filed in the case. In the above diagram, this means only using Appeal Docket 1 and Appeal Docket 2 (the first appeal filed for District Court Docket 2). This substantially simplifies conceptualizing the data because it produces a one-to-one relationship between civil action and appeal. This methodology allows us to obtain information about both whether an appeal is filed in a civil action at all and specifically what was the earliest appeal in a case.

While the use of only first appeals for each case won’t affect many of the analyses in this Article, such as questions about which patent infringement cases have an appeal or when the first appeal in a case was filed, it is possible it could affect other analyses, such as statistics on who files appeals. However, it does not appear to matter much for the attributes we examine in this Article. In general, most patent infringement cases with an appeal have only a single appeal rather than multiple appeals, and many cases that technically have multiple docketed appeals effectively have just a single appeal. Of the 2,941 civil actions that matched to an appeal docket as described below, 2,089 (71%) were civil actions with only a single docketed appeal; the remaining 852 civil actions had two or more docketed appeals. And of those 852 civil actions, 195 involved multiple appeals all filed on the same day.[64] Nevertheless, as a robustness check, we ran similar analyses on a dataset containing all appeals for cases filed between 2011 and 2016 (excluding appeals for the same civil action that were docketed on the same day) and obtained similar results for attributes that might be affected if all appeals are used. In addition, other types of analyses (such as comparing cases with only a single appeal versus those with multiple appeals) required using the “all appeals” relationship.

To match the district court and appellate records, we used a combination of the civil action number and the district that the case originated from. This required a series of algorithmic format standardizing steps. District court docket numbers were standardized to the same format used in the Stanford dataset, [division number]:[fiscal year of case]-[type code]-[five-digit suffix]. An example is 3:09-cv-03239. In addition, we developed a standardized “key” file to translate different formats used for district court names in different datasets.[65]

To assemble the “first appeal” dataset, we sorted the Federal Circuit dockets by the date the appeal was filed and kept only the earliest docketed appeal at the Federal Circuit in instances where there were multiple appeal dockets associated with the same district court case. We then automatically matched the appeal docket dataset to the Stanford dataset using the federal district name and civil action number.[66] Results were visually reviewed to confirm the matches.

In total, out of the 3,453 total first appeals docketed at the Federal Circuit from 2011 through 2021 that arose from the district courts, 2,941 matched a district court docket in the Stanford dataset. In other words, approximately 85% of the Federal Circuit appeal dockets arising from the district courts matched to a district court docket in the Stanford dataset.[67] Appeals in cases that did not match included issues such as inventorship, ownership, false marking, and review of patent office decisions relating to applications.[68]

Obviously, appeals are usually not filed at the same time that the case is filed. To ensure that appeals were not being truncated at the end of our time period, we compared the year the district court case was filed to the year the first appeal in the case was docketed at the Federal Circuit to determine the time between the filing of the patent infringement case and the first appeal in that action. Table 1 cross-tabulates the year the case was filed (rows) against the year the first appeal in that case was filed (columns).[69] The shading indicates the frequency of appeals for cases initiated at the district court in each year (i.e., along the rows).

Table 1 reveals that while appeals are sometimes filed in cases in the same year that the case itself is filed, more commonly appeals are filed one to three years after the case is initially filed.[70] However, over 95% of cases with an appeal had an appeal filed within six years of the initial case filing date.[71] Consequently, we limited our analyses to only cases filed in the district courts after January 1, 2011, (the earliest appeal in the set) and before December 31, 2016, (to minimize truncation of appeals at the end). For cases filed in the district courts during this time period, the average time from case filing to first appeal was about twenty-seven months, but with substantial variation: a standard deviation of eighteen months with rightward skew. In addition, because the appeals dataset is updated to include new appeals and cases as they are docketed and issued, future studies will be able to examine a longer time period.

We knew from previous studies that the vast majority of patent infringement cases filed in the district courts never result in even a single appeal.[72] To determine how many district court patent infringement cases actually result in an appeal, we looked at patent infringement cases filed in a district court between 2011 and 2016 inclusive. For cases filed during this six-year period, the percentage of district court patent infringement cases associated with an appeal was 5.6%. In other words, only about 6% of all patent infringement cases filed at the district courts resulted in an appeal. However, the percentage is not constant; rather, it steadily declined over the six-year period from 7.8% of cases filed in 2011 to 4.4% of cases filed in 2016.[73] Given that almost all first appeals are filed within six years of the patent infringement action being brought at the district court coupled with the peak number of patent appeals for cases filed in 2016 occurring in 2017, this decline is unlikely to be due to data truncation. Rather, there was a noticeable decline in the frequency of appeals filed in patent infringement cases.[74]

C. Appeals Filed to Appellate Decisions

Filing an appeal is only the first step in the appellate process. To develop the complete dataset, we matched the “first appeals” dataset of district court cases and docketed appeals to actual decisions by the Federal Circuit. Matching was done by using the appeal docket number from the appeal dockets dataset and corresponding information in the decision.[75] The matching was limited to only appellate decisions arising from the district courts.

Not all docketed appeals were resolved through a decision on the substance of the appeal. Of the 3,453 appeal dockets in the first appeal dataset that arose from the district courts, 2,104 (or about 61%) matched with an appellate decision.[76] This is consistent with our previous finding that about 63% of docketed appeals at the Federal Circuit are decided in an opinion or Rule 36 summary affirmance.[77] The remainder were terminated for various other reasons, including lack of appellate jurisdiction and voluntary dismissal of the appeal.[78]

Of the 2,104 appeal dockets that matched with an appellate decision, 1,915 arose from a case in the Stanford dataset. While there was a one-to-one relationship between each civil action and the first appeal docketed for that civil action, some (11%) of the Federal Circuit opinions and Rule 36 summary affirmances in this set involved multiple docketed appeals—and thus multiple underlying civil actions.[79] As a result, there are two possible levels of record units at which the decision data can be considered: on a per-appeal docket/civil action basis and on a per-decision basis. In total, there were 1,915 first appeals of a patent infringement case decided in 1,508 opinions and Rule 36 summary affirmances.[80] Of these, 1,155 appeals decided in 852 opinions and Rule 36 summary affirmances were associated with a case filed in the district courts between 2011 and 2016. Since each appeal in this set is associated with a different civil action, we primarily report data using appeals, not decisions, as the record unit.[81]

IV. Who Appeals Patent Cases

As previous researchers have shown, the vast majority of patent cases settle during litigation at the district court.[82] Our findings are consistent: only about 6% of patent infringement cases have an appeal, indicating that in the other 94% of cases, the parties have ceased to continue to litigate. In addition, only about 60% of those appeals result in a decision on the merits by the court—indicating further settlement during the appeal process.

Settlement rates can differ, however, by asserting entity type. Using a sample of 20% of the records in the Stanford dataset together with the data from Lex Machina, Miller et al. found that infringement cases filed by PAEs had a substantially higher settlement rate than actions filed by non-patent assertion entities.[83] Thus, our starting point for assessing the data on appeals was to look at the frequency of appeal by entity type. We then turned to other measures of appellant behavior: which party was the appellant, who “won” the appeal, and the manner in which the Federal Circuit judges chose to issue their decision.

A. Do Different Asserter Types Have Different Frequencies of Appeal?

The first issue that we examined is the type of PAE relative to the frequency of case filing and appeal. Our null hypothesis was that entity type does not matter. If entity type does not affect the selection of appeals, we would expect that these proportions should be about the same as those at the district court.

Hypothesis 1: The proportion of cases with appeals by asserter type should mirror the proportion at which the cases were filed at the district courts.

Table 2 shows the frequency of patent infringement cases filed at the district court using the Stanford dataset and the number of these cases with an appeal. Similar to Miller et al.'s findings, 1,838 (6.04%) of civil actions filed between 2011–2016 involved multiple categories of asserters; as in Miller et al., these are reported for each category type.[84] Figure 2 provides a graphical depiction of these rates for the four most frequent patent asserter case types.

Table 2 and Figure 2 show that although Category 1 (acquired patents) filed 37% of patent infringement actions 2011–2016, only 25% of appeals from cases filed between 2011 and 2016 arose from those cases. On the other hand, while product companies accounted for only slightly more patent infringement lawsuits (just over 40%), appeals in cases filed by product companies constituted 54% of all appeals filed. Cases filed by individuals, IP subsidiaries, and universities were also represented more frequently in appeals relative to cases filed. Thus, contrary to the first hypothesis (that the proportion of appeals will be similar to the proportion of cases filed), in actuality appeals from cases filed by Category 1 asserters comprise a substantially smaller portion of the appeal dockets than appeals from cases filed by Category 8 asserters.

B. Frequency of Appellate Decisions

Next, we investigated whether selection between appeal filing and decision affected the composition of appellate disposition. For this, we examined the frequency at which appeals reach an appellate decision on the merits (i.e., an opinion or Rule 36 summary affirmance). In total, 1,154 civil actions filed between 2011 and 2016 had at least one appellate decision associated with the action. Again, we begin with the hypothesis that, if there is no selection occurring at this stage, the proportions associated with each case type should be similar.

Hypothesis 2: The proportion of cases by asserter type with appellate decisions should mirror the proportions of appeals.

Table 3 and Figure 3 show the frequencies of docketed appeals and docketed appeals with an opinion or Rule 36 summary affirmance by case asserter category. Categories have been limited to only those with at least twenty-five docketed appeals.[85]

Overall, we find that the proportions by category of appeals with a decision are nearly the same as the proportion of appeals. 52% of appellate decisions in patent infringement cases arose from actions filed by a product company, 25% arose from actions filed by companies that acquired patents, 14% arose from actions filed by individual-inventor-started companies, and 8% arose from actions filed by individuals. In other words, the cases with decisions appear to largely mirror the composition of appeals filed. Put another way, once a case makes it to the Federal Circuit, decision rates in cases filed by PAEs and product companies are about the same.

C. Party Filing Appeal

The next issue we investigated is who is filing the appeal—that is, whether the appeal was filed by the patent asserter or the accused infringer. While we don’t have the data on who filed the appeal in the appeal dockets dataset, we do have information on the appellant in the appellate decisions dataset.[86]

There’s one observation that is important to make at the outset: overall, most appeals that result in decisions are filed by patent asserters, not accused infringers. 79% of appeals were filed by patent owners and only 21% by accused infringers.

But is this true across all patent asserter types? Again, we begin with the null proposition that who files the appeals is the same across patent asserter case types.

Hypothesis 3: The proportion of appeals filed by patent asserters should be the same across all patent asserter types.

Figure 4 depicts the relative frequency of who filed the initial appeal by case type. It presents a distribution of all appeals by type, separately indicating cases with multiple categories of patent asserters. Only the initial appellant (which we refer to as the “primary” appellant) is indicated.[87]

Figure 4 reveals some immediate characteristics: when looking at the overall percentage of appeals, appeals filed by product company patent asserters constitute the largest portion (31%), followed by appeals filed by companies that acquired patents (21%), and then accused infringers sued by product companies (14%).

Additional information is provided by Table 4 and Figure 5, which present information on the relative frequency of appeals by patent asserters and accused infringers for each asserter type. As with the tables in Sections IV.A–B, Table 4 and Figure 5 report cases with multiple categories of patent asserters.[88]

As with the overall rate, patent asserters for each category file most appeals in infringement actions. However, there is a striking difference in who files appeals in cases filed by different asserter types. When the patent infringement action is filed by a university, product company, or IP subsidiary of a product company, between 27–32% of the time the appellant was the accused infringer. On the other hand, when the infringement action was filed by a company that acquired the patents, individual-inventor-started company, or an individual, the rate was much lower—around 10%. Put another way, when a patent infringement case is filed by an entity that acquired the patent, the patent asserter is the appellant about 90% of the time. On the other hand, when a patent infringement case is filed by a product company, the patent asserter is the appellant just 70% of the time.

D. Party Prevailing on the Appeal

For this analysis, we treated an “affirmance” as a victory for the appellee, a “reversal” as a victory for the appellant, and an “affirmance-in-part” as a partial victory for the appellant.[89]

One complexity is the presence of cross-appeals. While most appeals (89%) resulting in decisions were not associated with a cross-appeal, for those appeals that were associated with a cross-appeal, about half were filed by the patent asserter and half by the accused infringer. The frequency of cross-appeals was about the same across all categories.[90] Cross-appeals complicate the analysis because an outcome such as a “reversal” may be a victory for the primary appellant or the cross-appellant. To mitigate this complexity, we limited the analysis to only appeals that were not associated with a cross-appeal.

At the outset, it is worth noting the substantial difference in affirmance rates when accused infringers file the appeal versus when the patent owner files the appeal. When accused infringers appeal, the Federal Circuit affirms the district court 63% of the time, but when patent owners appeal, the court affirms the district court 74% of the time—an 11% difference.[91] Correspondingly, affirmance-in-part and reversal rates are higher when accused infringers are the appellant than when the patent owner is the appellant. But are they the same for all types of cases?

Hypothesis 4: The rate at which the Federal Circuit affirms appeals filed by patent owners and accused infringers should be the same across all patent asserter types.

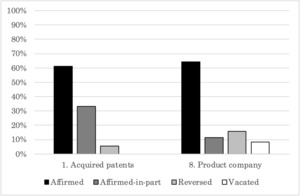

Figure 6 shows the outcomes of appeals when the patent asserter is the appellant. In other words, the patent asserter is challenging something that it lost on at the district court. For Figures 6 and 7, the black bars—“affirmed”—are bad for the patent asserter. “Affirmances” mean that the challenge was not successful—not the result the appellant is looking for. On the other hand, dark gray, light-gray, and white are all good, to some degree: they mean that the district court was not affirmed, at least in part. Keep in mind when viewing Figure 6 that categories 4, 6, and 12 have only about twenty records each.

Overall, when the patent asserter appeals, the decision of the district court is mostly affirmed, regardless of the type of patent asserter. Among the largest categories, product companies (70% affirmance rate), and individual-inventor-started companies (73% affirmance rate) fared the best, while companies that acquired patents (80% affirmance rate) and individuals (84% affirmance rate) fared worse.

The pattern is similar when the accused infringer is the appellant—although here, the affirmance rate is noticeably lower, and the difference is smaller. Figure 7 shows the outcomes when the appellant is the accused infringer for cases in which the patent asserter acquired the patent (eighteen records) and those filed by a product company (132 records). The other categories had only a handful of records.

Here, affirmance rates when the case was brought by a Category 1 (acquired patents) plaintiff are slightly worse than when the case is brought by a Category 8 (product company). When the appellant is the accused infringer, a “good” outcome for the patent asserter is an affirmance. In appeals brought by the accused infringer, the Federal Circuit affirmed 61% of the time when the case was filed by a Category 1 (acquired patents) patent asserter and 64% of the time when it was filed by a Category 8 Product company. In other words, when defending a district court decision, patent asserters who are Category 1 (acquired patents) fare almost identically at the Federal Circuit as Category 8 (product company) patent asserters. Note that because appeals filed by accused infringers are less common than appeals filed by patent owners, the data contains only nineteen appeals filed by accused infringers in cases filed by Category 1 patent asserters (as compared with 156 appeals filed by accused infringers in cases filed by Category 8 patent asserters).

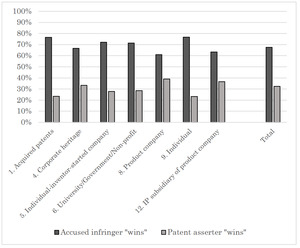

Finally, Figure 8 shows the relative rates at which patent asserters and accused infringers “win” by obtaining either an affirmance (if the appellee) or an affirmance-in-part, reversal, or vacate (if the appellant).

The composite data from Figure 8 suggests that, overall, product company patent asserters fare better on appeal than patent asserters that acquired patents. When the patent asserter is an NPE that acquired the patents (Category 1), the patent asserter “wins” on appeal only about 23% of the time. On the other hand, when the patent asserter is a company that practices the patent (Category 8), the patent asserter “wins” on appeal about 39% of the time. In Part V, we discuss some observations on this difference, including the important caveat that product companies are much more frequently defending a district court decision in their favor in the Federal Circuit than companies that acquire patents.

E. Type of Decision

While parties select the disputes to appeal and the arguments that they present on appeal, judges also play a role in selection. The most obvious is who prevails on appeal when there is indeterminacy in the law or facts: the appellant or the appellee. But judges engage in other acts of selection that shape the composition of the law. One key decision that judges make when affirming is whether to summarily affirm the district court or whether to instead write an opinion.[93] Under Federal Circuit Rule 36, the court may enter a judgment of affirmance without opinion when an opinion would have no precedential value and the record shows no error under the relevant standard of review.[94] Rule 36 judgments are thus thought of as “routine” affirmances.[95] Yet, there is substantial debate about the court’s use of Rule 36 affirmances: they provide no information about the reason for the court’s decision; they may lead to distorted perceptions about what the court is actually doing;[96] and in some cases, they may not be consistent with statutory requirements.[97]

At the Federal Circuit, 45% of docketed appeals are decided in an opinion, and approximately 17% of docketed appeals are summarily affirmed.[98] For patent infringement cases filed between 2011–2016, 47% of affirmances in infringement actions were summary affirmances through Federal Circuit Rule 36 and 53% of affirmances were via a written opinion. If the appeals from cases filed by different categories of patent asserters are otherwise similar, we should expect similar proportions across these categories.

Hypothesis 5: The proportion of opinions relative to Rule 36 affirmances should be the same across all patent asserter types.

The following table reports the proportions of affirmances that are via opinion versus Rule 36 for categories with more than thirty appeals. As described above, around 90% of appeals in cases filed by companies that acquired patents, by individuals, or by individual-inventor-started companies are filed by patent asserters, whereas a larger portion of appeals in cases filed by product companies are filed by the accused infringer.

Overall, 63% of affirmances in appeals filed by accused infringers were issued through an opinion rather than a summary affirmance, a result largely driven by outcomes in cases involving product company patent asserters. In contrast, when the patent asserter files the appeal, the rate at which the Federal Circuit issues its decision is less often an opinion: about 51–53% of the time.

V. Analysis and Discussion of Results

A. Who Appeals Patent Infringement Cases

Our initial observation is that, as with litigation at the district courts generally, the type of patent asserter matters when studying appeals. Cases filed by PAEs have disproportionately fewer appeals than cases filed by product companies. These cases tend to have more frequent settlements than infringement lawsuits brought by other types of patent asserters.

This is consistent with prior findings that PAEs settle more frequently than product companies. In a sample of 20% of the Stanford dataset, Miller et al. found that the settlement rate in cases filed by companies that acquired patents was 84% as opposed to only 63% for cases filed by product companies.[99] The more cases that settle at the district court, the fewer cases there are with the potential for appeal.

Why might this be so? The problem is not that there isn’t an explanation; the problem is that there are numerous possibilities. Allison, Lemley, and Schwartz, for example, offer a variety of possible reasons why PAEs may settle at different rates and the consequences of those theories.[100] It could be, for example, that PAEs assert patents against more parties. While the PAE settles with many of these parties, there’s a chance that a small number do not settle.[101] This would be consistent with a “nuisance value” approach to asserting with patents because most of these cases would settle before litigation proceeds very far.[102] Allison et al. also describe a “war chest” approach, in which the PAE settles its early cases with weaker parties then litigates aggressively against stronger parties.[103] This could result in a number of settlements together with a handful of cases that are litigated all the way to the Federal Circuit. A related explanation is the “aggressive reputation” concept, in which a PAE litigates aggressively initially in order to establish a reputation and signal the lengths to which it would go to litigate a dispute in order to more easily extract licensing revenue in the future.[104] Each of these could explain the higher settlement rates for PAEs, resulting in fewer appeals—but with different consequences for the strength of both the litigated and settled disputes.

More broadly, however, the answer to the question “who appeals patent cases” is, overwhelmingly, “patent asserters.” But from there, the answer becomes more complex. The most frequent group of appellants were product companies asserting their patents in the litigation, followed by PAEs. The third most frequent group of appellants, however, were accused infringers sued by product companies, followed by individual-inventor-started companies and individuals asserting their patents. Only a small portion of appellants were accused infringers sued by PAEs. Overall, product companies asserting their patents filed about twice as many appeals as PAEs asserting their patents, whereas accused infringers sued by product companies filed over five times as many appeals as accused infringers sued by PAEs.

Why are patent asserters usually the party filing appeals? The simple answer may be because, as Mark Lemley has observed, a patent owner must win on every issue—infringement and the multifaceted validity requirement—while an accused infringer need only win on one issue in order to prevail.[105] Thus, if a patent owner loses on any issue at the district court, it must appeal to keep the case alive, whereas an accused infringer can lose on an issue at the district court but still win the case if it wins on a different issue. And several studies have shown that patent owners only win the entire case (as opposed to a particular issue) about 25% of the time.[106] In addition, Miller et al. provides support for a differential win rate at the district court, with companies that acquire patents winning about 13% of the time as compared with product companies who won about 35% of the time for a sample of lawsuits filed 2000–2015.[107] If PAEs do lose more often in merits decisions at the district court, then it makes sense that they file appeals more frequently as well.

B. Who Wins Patent Infringement Appeals

Perhaps the most interesting part of our data for attorneys and litigants are the win rates. Both the patent asserter versus accused infringer win rates and the PAE versus product company win rates are sure to offer grist for debates about the patent system.

However, we think it’s important to provide some limitations for the data on win rates, especially for Figure 6. First, and most importantly, the data in Figure 6 combines appeals brought by both patent asserters as appellants and accused infringers as appellants. Because over 90% of appeals in cases filed by Category 1 plaintiffs are filed by the patent owner, and because the Federal Circuit affirms the district courts at a high rate, the result is that Category 1 patent asserters are typically fighting an uphill battle most of the time at the Federal Circuit. On the other hand, when the plaintiff is a Category 8 product company, over 25% of the time that patent asserter is the appellee at the Federal Circuit. And even though the Federal Circuit affirms district courts at a lower rate when the appeal is brought by the accused infringer as opposed to the patent asserter, it still affirms more often than it doesn’t. Thus, while there is some difference between the outcome of appeals depending on who the asserting party is, as shown in Figures 4 and 5, it’s important to also keep in mind who the appellant is in these appeals.

Another important limitation is the coarseness of our definition of “win.” We have defined a win as including some victory, such as an affirmance-in-part. It may be that the result obtained by a partial reversal is relatively insignificant in the full context of the litigation.[108] In addition, we did not separately break out cross-appeals. In future work, it would be beneficial to code cases with a cross-appeal at a more granular level; however, this will require a redefinition of the record unit.

There is also the inexorable presence of selection pressures, whether Priest-Klein, strategic, or something else entirely.[109] Systematic behavioral patterns may affect the disputes that arrive at the Federal Circuit to adjudicate, thus influencing parties’ win rates beyond what we have discussed here.

That said, the difference in affirmance rates for appeals brought by patent asserters versus accused infringers is worth more careful study. It may be that this is yet another example of the multiple-issue nature of patent litigation, manifesting on appeal, in which accused infringers have an array of possible issues to pursue while patent owners must win on everything.[110]

C. What Form the Federal Circuit’s Decisions Take

Our findings suggest that, at a first cut, cases filed by accused infringers sued by product companies are more likely to get an in-depth analysis, even if the decision of the district court is being affirmed. Whether this is because of judicial discretion or the nature of the case, however, requires further research.

A challenge with interpreting affirmances through Rule 36 is that there are two selective forces in play. On the one hand, the appeal brought by the appellant may itself involve an issue that is routine and thus subject to summary affirmance. On the other hand, the panel judges may choose whether or not to affirm through a Rule 36 or instead write an opinion. A Rule 36 affirmance requires agreement among all the judges on the panel, and the affirmance decision is not attributed to any single judge or group of judges. Instead, the panel acts “per curiam,” meaning in unanimous agreement.[111] Thus, the makeup of the panel and those judges’ Rule 36 rates may impact the likelihood of the case being decided by an opinion or a Rule 36 affirmance.[112]

That said, we observe that there is a notable difference if one looks only at precedential decisions as the lens through which to view the court’s decisions. For example, when considering only outcomes of precedential opinions, the rate at which product company patent asserters “win” at the Federal Circuit rises from 39% to 50% because a larger portion of appeals in which these patent asserters prevail as appellants are decided in precedential opinions. In other words, the lens through which we look at the decisions of the court matters: if we are only looking at precedential decisions, for example, we will see different outcomes than if we look at all decisions.[113] Given this, it is important to recognize that litigant selection is not the only selection that matters—judicial decisions about what to write about and make precedential do as well.[114]

VI. Conclusion

By linking together data on cases at the district courts and data on appeals at the Federal Circuit, we are able to provide a picture of who appeals patent cases. For patent infringement cases filed in the district courts between 2011 and 2016, most appeals are filed by patent asserters, not accused infringers. However, when accused infringers appeal, usually it’s someone being sued by a product company, not an entity that acquired its patents.

Not only are most appeals filed by patent asserters, but also patent asserters tend to do worse at the Federal Circuit than accused infringers. Even though the Federal Circuit affirms most of the time, it affirms a lot more frequently when patent asserters are the party seeking the court’s review. And this seems to be even more true when the appellant is a PAE.

Equally notable, however, is how the court releases its decision. As Chief Judge Moore observed over twenty years ago, and scholars such as Paul Gugliuzza, Mark Lemley, and Merritt McAlister have observed more recently, precedential opinions—or even all written opinions—are a judicially selected subset of the decisions that the court makes on appeals.[115] Precedential opinions are important but may not be representative of how the court decides appeals.

The central contribution of this Article, however, is an easy-to-apply methodology for linking datasets of district court cases to appeals and appellate decisions. This methodology can be employed to study an array of litigation characteristics using datasets beyond the Stanford NPE Litigation Database.

In particular, two additional areas of focus would provide greater information about the patent litigation ecosystem more generally. The first is to examine appeals in connection with the USPTO patent litigation dataset, which contains granular data on district court cases. It would be especially valuable to focus on cases with merits determinations to examine over a long period of time how frequently merits decisions are appealed and how those appeals are resolved at the Federal Circuit.

Second, while the approach here encompasses two components of the patent litigation system, district courts and appeals, there is another major component of current patent litigation over the past decade: inter partes review proceedings. These proceedings can impact infringement litigation in a variety of ways, including providing an alternate pathway for resolution of a determinative validity dispute between the parties that may dispose of the infringement litigation either because it drives the parties to settle or because it results in the invalidation of the asserted claims at the USPTO, thus effectively negating the litigation in the district court. Future research would benefit from incorporating data on the inter partes review proceeding into the relational data analysis we describe here.

See generally P.J. Federico, Adjudicated Patents, 1948–54, 38 J. Pat. Off. Soc’y 233 (1956).

See, e.g., Lee Petherbridge & Jason Rantanen, Infringement, in 2 Research Handbook on the Economics of Intellectual Property Law 326, 328–29 (Peter S. Menell & David L. Schwartz eds., 2019).

See George L. Priest, Selective Characteristics of Litigation, 9 J. Legal Stud. 399, 401–02 (1980); see also George L. Priest & Benjamin Klein, The Selection of Disputes for Litigation, 13 J. Legal Stud. 1, 7 (1984) (providing a further exploration of dispute settlement and selection).

See generally Alan C. Marco et al., Patent Litigation Data from US District Court Electronic Records (1963–2015) (USPTO, Econ. Working Paper No. 2017-06, 2017).

See generally Christopher A. Cotropia et al., Heterogeneity Among Patent Plaintiffs: An Empirical Analysis of Patent Case Progression, Settlement, and Adjudication, 15 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 80 (2018). For a discussion of the importance of public data accessibility, see Abigail A. Matthews & Jason Rantanen, Legal Research as a Collective Enterprise: An Examination of Data Availability in Empirical Legal Scholarship (Univ. Iowa Coll. L., Rsch. Paper No. 2022-10, 2022), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4057663 [https://perma.cc/WH7E-USJG].

For the importance of data sharing, see Jason Rantanen, The Future of Empirical Legal Studies: Observations on Holte & Sichelman’s Cycles of Obviousness, 105 Iowa L. Rev. Online 15, 24 (2020).

See, e.g., Jason Rantanen, Slaying the Troll: Litigation as an Effective Strategy Against Patent Threats, 23 Santa Clara Comput. & High Tech. L.J. 159, 165 (2006) (describing the debate over non-practicing entities in the early 2000s) [hereinafter Rantanen, Slaying the Troll].

See id.

See Colleen V. Chien, Of Trolls, Davids, Goliaths, and Kings: Narratives and Evidence in the Litigation of High-Tech Patents, 87 N.C. L. Rev. 1571, 1578 (2009); see also Colleen V. Chien, From Arms Race to Marketplace: The Complex Patent Ecosystem and Its Implications for the Patent System, 62 Hastings L.J. 297, 320, 326 (2010); Cotropia et al., Heterogeneity Among Patent Plaintiffs, supra note 5, at 86–87.

See, e.g., Rantanen, Slaying the Troll, supra note 7, at 165–66; see also Michael Risch, Patent Troll Myths, 42 Seton Hall L. Rev. 457, 462–63 (2012).

See, e.g., Risch, Patent Troll Myths, supra note 10, at 491, 493–94, 496–97; see also Shawn P. Miller et al., Who’s Suing Us? Decoding Patent Plaintiffs Since 2000 with the Stanford NPE Litigation Dataset, 21 Stan. Tech. L. Rev. 235, 238 (2018).

See, e.g., Chien, Of Trolls, Davids, Goliaths, and Kings, supra note 9, at 1578; see also David L. Schwartz & Jay P. Kesan, Analyzing the Role of Non-Practicing Entities in the Patent System, 99 Cornell L. Rev. 425, 428–29 (2014).

Christopher A. Cotropia et al., Unpacking Patent Assertion Entities (PAEs), 99 Minn. L. Rev. 649, 650 & n.3, 656–58 (2014) (attributing the term “patent assertion entities” to Colleen V. Chien).

See, e.g., Risch, Patent Troll Myths, supra note 10, at 474–91; see also Cotropia et al., Heterogeneity Among Patent Plaintiffs, supra note 5, at 100.

See, e.g., Cotropia et al., Heterogeneity Among Patent Plaintiffs, supra note 5, at 97; see also Risch, Patent Troll Myths, supra note 10, at 483; Miller et al., supra note 11, at 243.

See 28 U.S.C. § 1338(a) (“The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action arising under any Act of Congress relating to patents, plant variety protection, copyrights and trademarks.”); see also Gunn v. Minton, 568 U.S. 251, 257 (2013). Patent infringement lawsuits against the federal government are an exception: the Court of Federal Claims, not the federal district courts, have jurisdiction over these. See 28 U.S.C. § 1498(a); see also Judge Mary Ellen Coster Williams & Diane E. Ghrist, Intellectual Property Suits in the United States Court of Federal Claims, Landslide, Sept.–Oct. 2017, at 30, 31. One could also include proceedings before the International Trade Commission, but these are much less common than infringement cases in the district courts and possess different characteristics. See Jason Rantanen, The Federal Circuit’s New Obviousness Jurisprudence: An Empirical Study, 16 Stan. Tech. L. Rev. 709, 733 n.110 (2013).

Federal Courts Improvement Act of 1981, Pub. L. No. 97-164, 96 Stat. 25 (1982). In addition to appeals in patent infringement cases, the Federal Circuit also hears appeals from the USPTO, the Court of International Trade, the International Trade Commission, the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, the Court of Federal Claims, and other specific tribunals. See 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a) (describing the jurisdiction of the Federal Circuit); 38 U.S.C. § 7292(c).

See 28 U.S.C. § 1295. Note that petitions filed at the court, such as a petition for writ of mandamus or a petition for permission to appeal (as in the case of an interlocutory appeal) do involve discretionary components. See, e.g., 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b)–(c) (describing the federal court’s discretion to hear interlocutory appeals).

Risch, Patent Troll Myths, supra note 10, at 469–70; see also Michael Risch, A Generation of Patent Litigation, 52 San Diego L. Rev. 67, 77, 80–81 (2015).

Risch, A Generation of Patent Litigation, supra note 19, at 106–07, 124.

John R. Allison et al., How Often Do Non-Practicing Entities Win Patent Suits?, 32 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 237, 255–60 (2017) [hereinafter Non-Practicing Entities].

Id. at 258–59.

Id. at 269.

Id. at 272.

Cotropia et al., Unpacking Patent Assertion Entities, supra note 13, at 662; see also Cotropia et al., Heterogeneity Among Patent Plaintiffs, supra note 5, at 90.

See, e.g., Cotropia et al., Heterogeneity Among Patent Plaintiffs, supra note 5, at 100–02.

Cotropia et al., Unpacking Patent Assertion Entities, supra note 13, at 696.

Jay P. Kesan et al., Understanding Patent “Privateering”: A Quantitative Assessment, 16 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 343, 344, 347 (2019).

Miller et al., supra note 11, at 243.

NPE Litigation Database, Stan. L. Sch., https://npe.law.stanford.edu (last visited Oct. 26, 2022).

Id. at 242.

Id.

Id. at 267–69.

See, e.g., Cotropia et al., Heterogeneity Among Patent Plaintiffs, supra note 5, at 92; see also Miller et al., supra note 11, at 243; Kesan et al., supra note 28, at 361.

See, e.g., Risch, A Generation of Patent Litigation, supra note 19, at 77.

See, e.g., Jason Rantanen, Empirical Analyses of Judicial Opinions: Methodology, Metrics, and the Federal Circuit, 49 Conn. L. Rev. 227, 230 n.5, 238, 283–87 (2016) (listing over eighty empirical studies of the Federal Circuit) [hereinafter Rantanen, Empirical Analyses of Judicial Opinions]. See generally Ryan Vacca, The Federal Circuit as an Institution, in 2 Research Handbook on the Economics of Intellectual Property Law 105 (Peter S. Menell & David L. Schwartz eds., 2019). An existing gap in the literature is that while there is an excellent literature review of empirical studies of the Federal Circuit, see id., there is no comparable literature review of empirical studies of patent litigation in the district courts.

See, e.g., John R. Allison et al., Understanding the Realities of Modern Patent Litigation, 92 Tex. L. Rev. 1769, 1773 (2014) (examining litigation outcomes for patent infringement cases filed in 2008 and 2009); see also Jay P. Kesan & Gwendolyn G. Ball, How Are Patent Cases Resolved? An Empirical Examination of the Adjudication and Settlement of Patent Disputes, 84 Wash. U. L. Rev. 237, 259 (2006) (studying patent cases filed in 1995, 1997, and 2000).

See, e.g., Ryan T. Holte & Ted Sichelman, Cycles of Obviousness, 105 Iowa L. Rev. 107, 118 (2019).

See Allison et al., Understanding the Realities, supra note 37, at 1776–77.

Id. at 1775.

Id. at 1778–79.

Id. at 1779. This would suggest an appeal rate of approximately 5.5–7.1% (if the denominator is all cases) and 29–37% (if the denominator is merits decisions at the district court). See id. Notably, however, the authors recognized some substantial limitations of their study. Id. at 1776–77. In particular, changes in the law that took place between 2011 and 2014—particularly the enactment of the America Invents Act—limit the representativeness of their data for cases filed in more recent years. Id.

Id. at 1774–75.

See Jason Rantanen, The Landscape of Modern Patent Appeals, 67 Am. U. L. Rev. 985, 996 (2018) (describing the limitations of commercial databases).

See E.F. Codd, A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks, 13 Commc’ns ACM 377, 377 (1970).

See generally Jason Rantanen, Studying Patent Infringement Litigation, in Research Handbook on Empirical Studies in Intellectual Property Law (Estelle Derclaye ed., forthcoming) (on file with Authors).

NPE Litigation Database, supra note 30. The dataset has been continuously updated since the release of Miller et al. in 2018. Id.

There were fourteen records with duplicate district and civil action numbers in the Stanford dataset. Examination of the duplicates indicated that they appeared to be true duplicates, although in some cases information was missing from one of the records. Given the apparent duplication, the extra copies were dropped.

Miller et al., supra note 11, at 246–47, 251 (describing the methodology and tools used to categorize patent asserters).

Id. at 247.

Id. at 247–51. These contain the most frequent asserter types. See id. at 254. The other categories generally contain substantially fewer asserters. See id.

Id. at 247–48.

Id. at 244, 249.

Id. at 249.

Id. at 250.

Id.

Id.

The Compendium of Federal Circuit Decisions, U. Iowa | Fed. Cir. Data Project [hereinafter Compendium], https://empirical.law.uiowa.edu/compendium-federal-circuit-decisions (last visited Sept. 5, 2022). For a list of fields in the Compendium, see the project codebook, available at https://empirical.law.uiowa.edu/compendium-federal-circuit-decisions. Because this was the first time we used the AppellantType field, we conducted an intercoder agreement analysis by having a second person independently code a set of 200 records and comparing the coding for these records. The coders agreed on the coding for the AppellantType field 91% of the time. We then calculated Cohen’s kappa. Interpreting the kappa using Landis and Koch’s benchmark scale employing Gwet’s probabilistic-based method indicates “substantial” agreement. See Daniel Klein, Implementing a General Framework for Assessing Interrater Agreement in Stata, 18 Stata J. 871, 879–81 (2018); J. Richard Landis & Gary G. Koch, The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data, 33 Biometrics 159, 162–65 (1977). See generally Kilem L. Gwet, Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring the Extent of Agreement Among Raters (4th ed. 2014).

For a discussion of these petitions, see generally J. Jonas Anderson et al., Extraordinary Writ or Ordinary Remedy? Mandamus at the Federal Circuit, 100 Wash. U. L. Rev. (forthcoming).

Rantanen, Studying Patent Infringement Litigation, supra note 46 (manuscript at 11).

Id.

For more details on the relational nature between district court civil actions, appeals, and appellate decisions, see generally Rantanen, Studying Patent Infringement Litigation, supra note 46.

The exceptions are appeals in which the Federal Circuit took the decision en banc or the Supreme Court granted certiorari. These rare cases are excluded from the analysis and are more conducive to individualized analysis rather than big data-type approaches. Id. (manuscript at 7 n.28).

The appeals in Flexuspine, Inc. v. Globus Medical, Inc. are an example, which were both filed on November 9, 2016, and assigned appeal dockets 2017-1188 and 2017-1189. Flexuspine, Inc. v. Globus Med., Inc., 6:15-CV-201, 2016 WL 3536709 (E.D. Tex. Apr. 8, 2016). Samples of these appeals that we examined had virtually identical initial appeal docketing materials except for the appellate docket number assigned by the Federal Circuit and a minor detail, such as an additional docket entry at the district court.

For example, some datasets refer to the District of Minnesota as “D.Minn.” and others as “mnd.”

We used STATA’s merge function for this process, but it could be done using a variety of methods.

Accord Rantanen, Studying Patent Infringement Litigation, supra note 46 (manuscript at 16) (obtaining the same percentage for the same time period using the USPTO patent litigation dataset for the district court data).

See, e.g., DeVona v. Zeitels, 766 F. App’x 946, 949 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (nonprecedential) (involving an issue of inventorship); Taylor v. Iancu, 809 F. App’x 816, 816 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (per curiam) (nonprecedential) (reviewing USPTO denial of a patent).

In addition, there are 305 appeals docketed in 2011 and later from cases filed prior to 2009.

One reviewer asked about the prevalence of appeals involving preliminary injunctions in the dataset. Although we did not code for this information, a keyword search for “preliminary injunction” conducted on the decisions indicated that forty-eight of the appeals were associated with a decision that contained this term. As discussed below in footnote 88, almost all of these involved cases filed by product companies. See infra note 88.

For cases filed in 2011, 93% of cases with an appeal were docketed between 2011 and the end of 2016; for cases filed in 2012, 95% of cases with an appeal were docketed between 2011 and the end of 2017; for cases filed in 2013, 95% of cases with an appeal were docketed between 2011 and the end of 2018; for cases filed in 2014, 98% of cases with an appeal were docketed between 2014 and the end of 2019; and for cases filed in 2015, 99% of cases with an appeal were docketed between 2015 and the end of 2020. In addition, we observed an overall trend that the average time to first appeal in a patent infringement case has been getting earlier.

See Allison et al., supra note 21, at 255 & n.76.

The appeal rates for cases filed in each year were: 2011 (7.8%); 2012 (6.1%); 2013 (5.9%); 2014 (5.9%); 2015 (4.1%); 2016 (4.4%).

For example, for patent infringement cases filed at the district court in 2016, thirty-eight had their first appeal in 2019, while only five had their first appeal in 2021.

Full details of the process are provided in the project STATA code. See generally Replication Data for Who Appeals Patent Cases, supra note ∗.

Matching at this stage encompassed all appeals docketed at the Federal Circuit between 2011 and 2021. Note that some appeals docketed in 2020 and 2021 would not have been decided by the end of 2021.

Jason Rantanen, Response, Missing Decisions and the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, 170 U. Pa. L. Rev. Online 73, 75–76 (2022) [hereinafter Rantanen, Missing Decisions].

Id. at 84–86.

See generally, e.g., Eli Lilly & Co. v. Teva Parenteral Meds., Inc., 689 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (deciding appeal Nos. 2011-1561, 2011-1562, and 2012-1037).

To assess whether there were differences in the Stanford asserter category coding for appellate decisions involving multiple civil actions, we compared the Stanford asserter category for the first two civil actions associated with that appellate decision. Of the 179 decisions involving multiple civil actions, only ten (6%) differed in the category coding. Given the miniscule number of these decisions relative to the total number of decisions (1,508), we chose to proceed using just the civil action for which the appeal was filed first in the analysis where we used the appellate decision as the record unit. See NPE Litigation Database, supra note 30.

For reference, the “all appeals” dataset contains 2,281 unique appeals across 1,708 civil actions for cases filed in the 2011–2016 period.

See, e.g., Allison et al., Non-Practicing Entities, supra note 21, at 255 & n.76.

Miller et al., supra note 11, at 267.

See id. at 253–54 (finding that 6.9% of lawsuits involved multiple categories of asserters). Because of this, the total of the columns in Table 2 exceeds the number of cases and cases with appeals.

Percentages are based on the total number of appeals, including categories with fewer than twenty-five appeals.

There were twenty-nine appeals that indicated that the appellant was neither the patent asserter nor the accused infringer. These were coded as “other” and were not included in the analysis. In addition, one appeal record indicated that the appellant was “patent applicant.” This case (appeal uniqueID 13855; Stanford case_node_id 158792) was reviewed and determined to be a case involving a patent term adjustment claim; it, too, was dropped from the analyses in this section. Nine records were missing this information.

In other words, this data does not reflect cross-appeals. There were 126 (out of 1,154 total appeals with a decision) with a cross-appeal.

One reviewer asked about the relevant proportions of appeals involving preliminary injunctions. Although the data does not currently contain this information, we conducted a word search on the document dataset for the term “preliminary injunction.” We found that forty-six (out of 581) initial appeals in cases filed by product companies resulted in an opinion that contained this term, whereas none of the decisions involving cases filed by Category 1 or 4 patent asserters contained this term, and only one to three of the decisions involving cases filed by other categories contained this term. This does not necessarily mean that 8% of appeals involving cases filed by product companies involve a request for a preliminary injunction, but it does suggest yet another difference between appeals in cases by product companies and appeals in cases filed by other asserting entities. See Ryan T. Holte & Christopher B. Seaman, Patent Injunctions on Appeal: An Empirical Study of the Federal Circuit’s Application of eBay, 92 Wash. L. Rev. 145, 183 (2017) (discussing permanent injunctions on appeal at the Federal Circuit).

For a discussion of why these definitions are important, see Rantanen, Empirical Analyses of Judicial Opinions, supra note 36, at 255.

The two largest case type categories had nearly the same frequency of cross-appeals: Category 1 (11% of appeals were associated with a cross-appeal) and Category 8 (13% of appeals were associated with a cross-appeal).

As a robustness check, we calculated this rate for all appeals docketed 2011–2021 and obtained nearly identical results (64% affirmance rate when accused infringer is the appellant and 75% affirmance rate when patent asserter is the appellant).

Numbers for Figures 6–8 are provided in the Excel file in the data repository. See generally Replication Data for Who Appeals Patent Cases, supra note ∗.

See Kimberly A. Moore, Are District Court Judges Equipped to Resolve Patent Cases?, 15 Harv. J. Law & Tech. 1, 8 n.36 (2001).

Fed. Cir. R. 36(a)(1).

Rates Tech., Inc. v. Mediatrix Telecom, Inc., 688 F.3d 742, 750 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (“[A] Rule 36 judgment simply confirms that the trial court entered the correct judgment. It does not endorse or reject any specific part of the trial court’s reasoning. In addition, a judgment entered under Rule 36 has no precedential value and cannot establish ‘applicable Federal Circuit law.’”).

Paul R. Gugliuzza & Mark A. Lemley, Can a Court Change the Law by Saying Nothing?, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 765, 767 (finding that “the Federal Circuit writes precedential opinions much more frequently when it rules in favor of the patentee than when it invalidates the patent” in the context of decisions involving section 101 of the Patent Act).

Dennis Crouch, Wrongly Affirmed Without Opinion, 52 Wake Forest L. Rev. 561, 571 (2017) (arguing that the Federal Circuit’s practice of no-opinion judgments is contrary to law).

Rantanen, Missing Decisions, supra note 77, at 80.

See Miller et al., supra note 11, at 267; see also Allison et al., Non-Practicing Entities, supra note 21, at 255, 289 (finding that 90% of patent infringement cases filed in 2008 and 2009 settled before a decision on the merits).

Allison et al., Non-Practicing Entities, supra note 21, at 255–56.

Id. at 284.

Id.

Id. at 285–86.

Id. at 285; Rantanen, Slaying the Troll, supra note 7, at 165–66.

Mark A. Lemley, The Fractioning of Patent Law, in Intellectual Property and the Common Law 506 (Shyamkrishna Balganesh ed., 2013).

See Allison et al., Non-Practicing Entities, supra note 21, at 269; Paul M. Janicke & LiLan Ren, Who Wins Patent Infringement Cases?, 34 AIPLA Q.J. 1, 8 (2006); Miller et al., supra note 11, at 269 (finding a 29% win rate on merits decisions at the district courts).

See Miller et al., supra note 11, at 269; see also Allison et al., Non-Practicing Entities, supra note 21, at 269–72 (showing an approximate win rate of 31% for operating companies and 14% for NPEs).

An example is University of Massachusetts v. L’Oréal, S.A. See generally Univ. of Mass. v. L’Oréal, S.A., 36 F.4th 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2022). For an explanation of this case, see Jason Rantanen, U Mass v L’Oréal: Avoiding Indefiniteness Through Claim Construction, PatentlyO (June 15, 2022), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2022/06/avoiding-indefiniteness-construction.html [https://perma.cc/9Z85-K4JC].

See Allison et al., Non-Practicing Entities, supra note 21, at 282; Rantanen, Empirical Analyses of Judicial Opinions, supra note 36, at 242–44.

Lemley, supra note 105, at 506, 508–09; Jason Rantanen, Why Priest-Klein Cannot Apply to Individual Issues in Patent Cases (manuscript at 3–8) (Univ. Iowa Legal Stud., Rsch. Paper No. 12-15, 2012), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2132810 [https://perma.cc/WR58-2LW3].

Rantanen, The Landscape of Modern Patent Appeals, supra note 44, at 993.

See id. at 1028–32 (describing the data on each individual Federal Circuit judge’s Rule 36 rates).

Merritt E. McAlister, Missing Decisions, 169 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1101, 1147 (2021); Rantanen, Missing Decisions, supra note 77, at 86; Gugliuzza & Lemley, supra note 96, at 806–08.

Accord Kimberly A. Moore, Markman Eight Years Later: Is Claim Construction More Predictable?, 9 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 231, 234–35 (2005) (describing the implications of focusing only on published opinions and omitting summary affirmances); McAlister, supra note 113, at 1106–07; see also Jason Rantanen, The Federal Circuit’s Precedent/Outcomes Mismatch, PatentlyO (July 5, 2022), https://patentlyo.com/patent/2022/07/circuits-precedent-outcomes.html [https://perma.cc/8Z9N-23RV].

See supra notes 93–96 and accompanying text.