I. Introduction

Over a decade of scholarship has examined the questions associated with “Election Security” and “Election Hacking.” Overwhelmingly (if not exclusively) these efforts have focused on the critical questions associated with maintaining the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of voting information systems.[1] The results are compelling—there are substantial vulnerabilities in existing systems.[2] Much of this research suggests solutions for how to mitigate, deter, or detect exploitation of those vulnerabilities.[3] Put differently, there are available solutions, both technological and legal.[4] Furthermore, in the event such “alteration[s]” to voting records were detected, both legal and political redress mechanisms are available or could be made available under our current constitutional framework.[5] Election Hacking is a problem, albeit difficult, which can both be managed and for which redress exists.

So, what happened in 2016? Some conservative commentators argue that U.S. voters simply preferred then-candidate Trump over Secretary Clinton.[6] They are exactly correct . . . if perhaps not for the reasons they suspect. The federal elections of 2016 and 2020 are hotly debated topics pertaining to foreign intelligence Influence Operations and provide the two most rich examples of elections in recent U.S. history where foreign activities may have impacted the outcome.

Overwhelming evidence exists suggesting that foreign intelligence and espionage agents engaged in complex campaigns designed to influence the outcome of the 2016 national election.[7] As of the time of this writing, some evidence exists for such activities pertaining to the 2020 election as well.[8] Such activities clearly would be unlawful under U.S. law,[9] and there is a strong argument that the conventions of international law prohibit these activities as well.[10] But regardless of either prohibition, the effect remains—people either changed how they voted or whether they voted.[11] And they did so voluntarily, thus rendering any legal redress impossible and political redress extraordinarily unlikely.

This Article argues that the 2016 U.S. presidential election illustrates a critical example of the vulnerabilities of representative democracy in the context of a highly interconnected, “cyber” world. (As of the time of writing, insufficient information was available for a similar analysis regarding the 2020 election, however this Article argues that the proposed framework remains appropriate for future work examining that election once adequate information becomes available.) Part II describes a typology for distinguishing these challenges from other types of electoral interference. Attempts to persuade an individual whether or how to vote, or “Influence Operations,” are nothing new—individuals and governments have spent enormous resources (lawfully and unlawfully) throughout history attempting to persuade voters to act one way or another.[12] What changes in the Information Age is the ability to execute such operations, cost-effectively and at scale. Coupled with the ability to disguise the identity or origin of those operations, the desired effect can be achieved—“persuading” enough voters to alter an electoral outcome. Part III discusses the limitations of current technological and legal solutions at countering these types of interference.

Part IV examines the possible solutions remaining given the challenges identified in Part II and the limitations discussed in Part III. It focuses primarily on those aspects of Influence Operations that focus on persuasive messaging, which this Article argues is the most significant challenge currently facing the United States in mitigating the effects of unlawful foreign election interference. Part III highlights the fundamental challenges inherent in combatting Influence Operations, which, at their core, are persuasive political speech.

Notwithstanding these tensions, the conclusions of this Article are not bleak. First, “traditional” Election Hacking is an imminently mitigable problem, at least without the added complexities of so-called online voting.[13] Second, protected speech cuts both ways—the ability of those who identify “fake news” to brand it so and spread that counter-message at low cost enjoys the same benefits of the Information Age as those that enable low-cost Influence Operations at scale.[14] Third, there are actions that the government, social media platform operators, and individuals can take within current law that show significant promise for mitigating the effects of Influence Operations.

The primary goal of this Article is to shed light upon a previously under-explored area of law regarding election interference through cyber means of persuasion. The visceral reaction of many to feeling disenfranchised in 2016 through so-called fake news raises the specter of reactionary policymaking that threatens fundamental constitutional principles—a process that already has begun.[15] The conflicting information regarding the procedures and procedural security of the 2020 election only exacerbated this effect and further eroded trust in institutions.

By developing a framework for understanding the scope of electoral interference problems and identifying the legal and technical challenges and options for responding to such problems, this Article seeks to inform the policy debate to craft effective deterrence, mitigation, detection, and redress mechanisms before such problems occur again. The greatest victory of a foreign adversary in this context is not in getting their favored candidate elected (although such would not be insignificant)—it is in undermining the electorate’s confidence in elections, a process that ultimately leads to political destabilization. By addressing these problems up front, we can, at the very least, substantially reduce any loss of confidence resulting from future unlawful electoral interference operations.

II. Influencing Elections

The 2016 U.S. federal election was the first U.S. election to draw substantial attention to the question of foreign interference in national elections. While hardly the first such instance of foreign interference in a national election,[16] several factors distinguished the 2016 case as a “first of its kind.”[17] The political polarization of the parties and the candidates in the presidential election, the vastly different policy directions the United States was likely to follow under each electoral outcome, and the scope and scale of the U.S. domestic and foreign policy influence distinguishes this result from any other contemporary example.[18] When combined with the narrow effective margin of victory,[19] the net result elevates the question of foreign influence to a level not previously experienced in contemporary history.[20]

A substantial portion of this attention focuses on the related concepts variously described as election “hacking,” “meddling,” “interference,” or other similar terms.[21] This Article will refer to the problems posed by these related terms simply as “election interference.” This term does not yet have a widely accepted formal definition but has been used extensively by government officials, public figures, and the media of record to describe variations on electronic or cyber activities designed to alter the outcome of an election. While an energizing term, whose imagery aligns well to a cyber-oriented view of contemporary society, this term is both technologically misleading and frames a distorted view of the fundamental legal questions confronting foreign influence on elections.

Unlawful efforts to alter the results of elections generally come in two forms: (1) efforts to “alter” official voting records (Election Hacking); and (2) efforts to “persuade” individuals how to vote (Influence Operations). Within each group, under current U.S. law, there generally are two primary “attack surfaces”[22]—vote choices and voting ability (registration/turnout).[23] Efforts to alter voter records are best understood as Election Hacking because they are targeted at the election infrastructure itself, in an attempt to compromise or otherwise interfere with the normal operation of those systems. Efforts to persuade individuals how or whether to vote are best understood as Influence Operations[24] because they are independent of election infrastructure and focus on influencing voter behavior.

This Article focuses primarily on Influence Operations. It argues that extant legal systems and technological solutions are capable of producing a combination of deterrence, mitigation, and redress mechanisms that are sufficient (if technologically challenging) to manage the risks of Election Hacking. Influence Operations, by contrast, are technologically difficult to mitigate (and impossible to prevent). Furthermore, legal mechanisms for mitigation and deterrence of Influence Operations are constitutionally problematic, and ex post legal redress is effectively impossible.[25]

This Part begins with a brief discussion of what should be called Election Hacking—those activities involving compromising election infrastructure directly—and a discussion of why that category of problems, while vitally important, presents a different set of questions than those posed by the types of Influence Operations that are the focus of this Article. This typology distinguishes among the types of activities involved in election interference and frames these categories for a discussion of the limits of technological and legal solutions (in Part III) and the approaches that remain (in Part IV).

A. Election Hacking

Election Hacking can be a misleading term. It evokes imagery of using technological means to compromise or otherwise alter information or systems. This Article argues therefore that Election Hacking is better understood as a specific subset of unlawful election interference dealing with threats to election infrastructure and records and distinguishes these activities from attempts to influence voter behavior. Section II.B, Influence Operations, deals with those methods designed to alter how or whether an individual exercises their lawful voting choice. Election Hacking, by contrast, is not concerned with voter persuasion.[26] Put simply—Influence Operations are not Election Hacking.[27]

1. Altering Recorded Votes

Perhaps the most easily recognized form of electoral interference is the concept of altering recorded votes. This category encompasses a wide variety of actions, all of which result in some alteration of ballots or counts of votes resulting, or otherwise cause a vote count result that does not match voters’ actual choices. The most common colloquial example of this is the vision of foreign adversaries remotely connecting to and altering the results tally in electronic voting systems. However, it is important to note both that: (1) “remote” connections are not the only attack vector; and (2) the voting machines on which individuals cast their ballots are not the only attack surface.[28] The collective system responsible for recording, transmitting, aggregating, and storing election results comprises the attack surface and provides many opportunities for administrative, technical, and physical attacks.[29]

The concept of altering recorded votes is not new in principle and the example of “ballot box stuffing” dates back decades, if not centuries.[30] Physical methods like this, some of which were employed in the 2018 federal midterm elections,[31] essentially seek to achieve the same goals as “cyber election hacking” methods. Cyber methods, however, introduce a new dimension to the process of changing vote records—the ability to execute large-scale attacks that scale at low marginal cost and force defenders to engage in substantially higher expenditures to mitigate risk than otherwise would be the case with physical balloting systems.[32]

The result is something akin to a “Cyber Space Race,” not dissimilar from that found in traditional attacker-defender cybersecurity adversarial models,[33] in which unlawful actors compete against state and federal “defenders” to achieve the ability to modify election data. Much scholarship and scientific research has examined these problems,[34] and the results are promising, if not daunting.

It is the promising aspects of that work that are relevant to this Article. While it is true that current electronic voting systems are vulnerable to varying degrees,[35] and addressing those vulnerabilities is a complex and difficult engineering task,[36] the nature of these vulnerabilities bears two key characteristics relevant to the doctrinal questions of addressing election hacking.

First, this work suggests that most of the present vulnerabilities in election systems can be addressed and that ongoing mitigation strategies can substantially reduce the risk of future compromise.[37] Indeed, that federal and state election authorities[38] repeatedly confirmed that there was no evidence of election infrastructure compromise in the 2020 elections[39] presents strong evidence of the plausibility of managing risk through these approaches.

Second, to the extent that some attacks are successful, notwithstanding mitigation efforts, the impact of the external operations to alter votes (“hacking”) is redressable. While the mechanism of redress may remain a subject of debate (and is outside the scope of this Article), it is clear that at least one of a state or federal agency, an executive, a court, or a legislature will have the ability to examine such evidence and take remedial action based upon that evidence. To the extent some jurisdictions may presently lack the sufficient remedial authority, such a grant is unlikely to pose federal constitutional problems such as those discussed in Section II.B.

In this key respect of redressability, Election Hacking threats related to vote alteration are substantially different from Influence Operations in that they are manageable through legal and technological solutions that do not necessarily conflict with other constitutional and fundamental principles of representative government. In addition to the plausibility of significant mitigation through technological measures, post-election redress measures not only are available but are not a new challenge and indeed have been invoked and utilized before.[40]

2. Altering Voter Registration

This category encompasses the breadth of actions designed to alter the ability or “authorization” of an individual to vote, such that they either are unable to vote or the process of casting their vote is more difficult. Like altering vote records, this fundamental concept is nothing new. Legal voting restrictions and impediments such as property ownership requirements, poll taxes, literacy tests, and other similar mechanisms are centuries old.[41] Technical voting restrictions and other impediments, such as voter intimidation, have also existed throughout history.[42]

Altering voter registrations follows a similar analysis to that for altering recorded votes. While invalidating or failing to certify an election result based on a lack of ability of voters to vote may pose more complex political questions,[43] those questions still are fundamentally redressable without infringing upon other constitutional principles. Indeed, many of the examples depicted not only were actually redressed[44] but the policies used to redress those actions were themselves subject to ongoing evaluation.[45] This Article does not discuss the political desirability or policy efficacy of those measures. The fact that the political process engaged and addressed these problems is evidence of their amenability to constitutionally permissible policy solutions—the key distinction from problems posed by Influence Operations.

B. Influence Operations

Influence Operations also are a subset of unlawful election interference. Unlike Election Hacking, however, Influence Operations focus on persuading individuals either how to vote or whether to vote. Influence Operations present a problematic scenario for deterrence and mitigation efforts because political speech is at the core of such activities.

Perhaps even more troubling, they present a currently unsolvable problem for redress. In the presence of Influence Operations—even ones that can be properly criminalized or otherwise declared unlawful—the result of those activities causes an individual to vote differently or change whether or not they vote at all. In either case, however, the individual has lawfully made the choice how and whether to vote. Under current law, therefore, no authority would have a proper legal basis for failing to certify an election result. Solutions that declare individual votes “invalid” because a lawfully registered voter had been “influenced”—even if by a foreign adversary—may themselves commit the very acts those solutions seek to prevent. If the polity is the ultimate source of political authority and legitimacy, then what other authority than “the people” could be empowered to determine an individual’s vote not to have been of their own free will? And what mechanism other than voting could the polity have for expressing such a preference regarding the validity of an election?[46]

Political solutions may remain—in a presidential election, for example, via the Electoral College in jurisdictions without “faithless elector” prohibitions. Legal redress would be precluded, however, because voters’ choices were not frustrated—they just were persuaded to do something differently.

Understanding the threat to democratic elections through unlawful[47] Influence Operations is critical. It not only was a subject of substantial activity in the U.S. Intelligence Community during the years 2016–2020[48] but it also creates a deeply problematic situation where two different core principles of representative democracy are placed at odds with one another. On the one hand, free political speech is a core tenet of democracy. Political campaigning, which at its core is persuasive messaging, is the quintessential example of protected political speech.[49] On the other hand, the right of each individual to participate equally and free of coercion in democracy also is a core value, and this arguably includes freedom from influence that the government has prohibited (e.g., physical coercion, foreign influence, etc.). This section explores the nature and character of Influence Operations and lays groundwork for understanding the challenges of balancing the competing values inherent in representative democracies.

1. Influencing Voter Ballot Choices

The concept of influencing voter ballot choices is perhaps the most problematic category of electoral interference. It does not involve modifying election data or compromising election infrastructure. Rather, it seeks to influence a voter’s decision-making processes through persuasion, usually by promoting false, misleading, divisive, or emotionally charged political messaging. The goal of this activity is to interfere with the outcome of an election by persuading a voter to vote differently.

This persuasion-based approach is precisely the problem—it is incredibly difficult to distinguish from a different category: core political speech. Consider, for example, a presidential debate. The core function of such an event is, through the candidates’ discussion and debate of policy matters and other political issues, to help voters make decisions regarding whom they wish to vote for. The challenging question inherent in this category, then, is how we can create an articulable delineation between lawful and unlawful activity.

2. Influencing Voter Turnout

The concept of influencing voter turnout bears many similarities to influencing voter ballot choices but has categorical distinctions that are important to understanding how legal frameworks can address the set of such activities generally considered to be inconsistent with democratic or republican governance. At its core, this category also is about influencing voter decision-making choices. Unlike influencing ballot choices, however, influencing voter turnout need not employ measures related to political or any other potentially protected speech.[50]

Voter turnout is affected by a wide variety of factors.[51] These factors extend far beyond mere levels of satisfaction with the available candidates or interest in the listed ballot measures. Logistical factors including transportation, weather, and familial and professional obligations all have been shown substantially to impact voter turnout, particularly for the archetypical marginal or “undecided” voter.[52] Less motivated voters, for example, may be deterred from voting in the presence of inclement weather or transportation difficulties.[53] There is also some evidence that such voters might also be deterred in national elections following early polling reports indicative that their candidate of choice may lose (or, for that matter, win) the national election regardless of their vote.[54] In a world increasingly relying upon modern information services for up-to-the-second information regarding weather, traffic, and electoral results, the ability to insert false information into common information services may be sufficient to alter the choices of voters to vote at all in key districts statistically likely to vote in a certain direction such that the outcome of an election can be influenced by a foreign or other potentially unlawful actor. Unlike the third category above, however, such “false” information likely would not fall under any form of protected speech and furthermore likely would be capable of being (if not already) criminalized under other existing laws such as fraud and computer crime statutes.

While this Article generally treats the persuasion-oriented aspects of these two categories as facing the same set of problems, the distinctions identified above are considered separately as “corner cases” because the availability both of technological and of legal solutions are different for a variety of reasons. These distinctions are discussed further in Part III.

III. The Limits of Technological and Legal Solutions

When faced with a cyber problem there is a natural tendency to look for cyber (i.e., technological) solutions. And in many such cases technological solutions will indeed lead the way.[55] In the context of election interference, however, the protected speech-like nature of many Influence Operations makes technology-based solutions difficult, or at least incomplete. It is extraordinarily difficult for automated, technological solutions to distinguish between protected political speech and a form of fake news planted by an agent of a hostile foreign power.[56]

In the context of Election Hacking operations, the technological prognosis is much more favorable. Extensive research and analysis suggest that effective technological solutions, buttressed by some policy reforms, can provide effective mitigation of many (if not most) Election Hacking operations.[57] While it may be a difficult engineering challenge, it is not an impossible one—unlike the current near impossibility of technologically combatting Influence Operations.

This Part therefore focuses primarily on exploring and describing the limits of technological solutions to addressing Influence Operations. It begins with a description of the proverbial “whack-a-mole” problem presented by cyber operations—the ability of adversaries to easily adapt and redeploy their tools, techniques, and practices at low cost when a defender detects and identifies the adversary.[58] It then proceeds to discuss the challenges and opportunities for using technological solutions in the context of each of the four categories identified in Part II.

A. The “Whack-a-Mole” Problem

One of the greatest challenges created by the internet and modern information technologies is the massive reduction in the transaction costs associated both with (1) the production of the next copy of content;[59] and (2) the switching costs of implementing a new “tool” or method of operation.[60] While existing literature discussing transaction cost reductions in the Information Age discusses a slightly different context than the question here, the concepts are to some extent relevant. In brief, this body of work identifies that the cost of production of a marginal digital copy is near zero[61] and the switching costs for end users of implementing a new tool or technology have changed (at least characteristically) as compared to early or pre-software goods.[62] The net result of these effects, and ones similar to them in the context of various cyber adversaries,[63] is that cyber adversaries—those seeking to use modern technology to achieve unlawful or otherwise undesirable ends—are able to “shift” from approach to approach with a level of ease previously not imagined. Put simply, attackers will quickly and easily find any defensive vulnerability.

Assuming these propositions are correct,[64] the result is an environment in which attackers may have the capacity not only to switch among technical methods of attack but also to switch among behavioral or logistical methods of attack. In other words, if an adversary determines that one attack method has become too risky or costly, they can easily (and likely quickly) switch to another such method. By way of example, if someone attempting to influence an electoral outcome through social media “trolling”[65] discovers that the particular country of origin where they have rented time on “botnets”[66] has implemented stronger criminal law protections or international law extradition/MLAT[67] cooperation agreements, the adversaries could simply switch the provider from which they rent time to one in a jurisdiction lacking such legal impediments. Likewise, if that adversary finds that a particular technical measure has been implemented, such as a perimeter-based filtering mechanism for known unlawful or misleading content, the adversary can simply alter the nature of the content or employ other technological measures to bypass that perimeter defense. One need only look to the (in)efficacy of the so-called Great Firewall of China to see how such measures easily can fail against sophisticated adversaries.[68]

This problem poses substantial challenges both for legal and technological solutions. If these claims are correct, no single legal nor technological tool is likely to be an effective solution—or even an effective mitigation—against unlawful Influence Operations. Within the context of election interference there are a wide variety of methods of interference and numerous technical tools to implement those methods.[69] Thus single-solution approaches become an invitation for adversaries to use them as “roadmaps for attack.” An adversary need only look to the legal prohibitions or technological solutions in place to determine what defenses have been used, and therefore what defenses have not been used. That adversary then focuses its efforts on the vulnerable areas—the “mole holes” that are not “covered.”[70]

In a manner similar to some legal solutions, technological solutions present an attractive method of addressing electoral interference. Just as one might argue “pass stronger criminal laws” as a solution, another might argue in favor of “requiring stronger technical defenses.” Unfortunately, just as the former misunderstands the legal landscape, the latter misunderstands the nature of the technological landscape and the limitations of technological solutions.

B. A Typology of Election-Interference Solutions

Threats related to Election Hacking and those related to Influence Operations pose fundamentally different technological questions. In the most abstract sense, Election Hacking threats deal with a complex system security problem, whereas Influence Operations deal with an information warfare and psychological operations problem. While it is true that, generally speaking, these tactics can be used in concert (e.g., a “phishing” email[71]), in the context of securing elections they are essentially separate issues. This separation in the election context results primarily because the relevant technological systems to Election Hacking generally do not overlap with those used in election Influence Operations. Election Hacking threats primarily target the infrastructure in use by elections officials, whereas Influence Operations primarily are conducted through public or quasi-public fora like social media platforms.

This Section focuses primarily on the technological challenges present in mitigating threats from Influence Operations. The field of inquiry addressing threats from Election Hacking is well studied by comparison,[72] and while it remains a challenging engineering problem, it can be distinguished from a legal standpoint as discussed in Part II.

1. Election Hacking and Record Alteration

In the United States, voting systems and voter information systems include a wide variety of implementations.[73] New ideas are being proposed and tested at a rapid pace.[74] This makes for a complex and challenging environment in which to deploy cybersecurity measures. Doing so for complex systems already is a generally difficult challenge in computing and information science,[75] and this challenge is worsened by the nature of U.S. elections as being “among the most operationally and logistically complex in the world.”[76]

From a legal perspective, technological solutions for protecting vote counts and for protecting voter registration are similar.[77] The problem at issue is the unauthorized access to or alteration of those records, and the goal is the prevention of such threats—or at least their mitigation to an acceptable level of risk.

Yet notwithstanding the complexity of this problem, technological solutions exist that can reduce the legal questions to manageable ones. While it is, of course, impossible to guarantee detection of all unauthorized alteration of information in complex software systems,[78] it is quite possible—and practical—to employ technological methods that maximize the probability of detecting unauthorized access.[79] This is particularly important from a legal perspective because it opens up the possibility of legal redress. Laws and institutions can be designed (and indeed many already exist[80]) that address what steps are taken to detect and, in the event of detection, to redress unauthorized access or alteration of election records. In effect, technology and law together can adequately handle this problem.

And indeed, in the 2020 U.S. elections, the overwhelming majority of officials responsible for election administration—including those from the political party that fared less favorably in the presidential and federal congressional contests—vigorously agreed that the 2020 election was “the most secure in American history.”[81] While significant allegations of “election fraud” were levied after the 2020 election results were announced,[82] those allegations did not pertain to compromise of the technological systems by foreign actors, but rather nonfeasance, misfeasance, and malfeasance by officials administering the elections, unlawful vote casting by individuals, or both.[83] Even were these allegations true, they would not undermine the efficacy at preventing the technological types of Election Hacking contemplated by this Section.

To be sure, cybersecurity practices to defend against Election Hacking are a difficult challenge, one not to be underestimated, one that requires a substantial amount of resources, and one that will continue to evolve with the state of technology.[84] But nothing about the nature of the problem necessarily brings into conflict multiple of our core democratic values.

2. Influencing Voter Choices

Influence Operations remain perhaps the most difficult and most challenging technological problem to address. Interestingly, the challenges from a constitutional and First Amendment perspective that the law faces in addressing Influence Operations are very similar in structure[85] to those technological solutions face: it is difficult to differentiate between “protected” and “unlawful” forms of speech.

At their core, Influence Operations targeted at voter ballot choice or voter turnout seek to achieve one goal–to influence how or whether a voter casts their vote. The zenith of protected political speech—messaging about a candidate or party and their policy positions—also seeks to influence how or whether a voter casts their vote. Perhaps one of the most dangerous and disingenuous assumptions about unlawful Influence Operations is that the substance of their speech somehow is categorically distinguishable from protected persuasive political speech.[86] While it may be true that some individuals have preference-based heuristics by which they draw such distinctions, such heuristics neither are viewpoint-neutral categorical distinctions nor are they capable of being encoded into the types of automated systems that would be required for technological “filters” to distinguish based on the content of a message. Put simply, the messaging in protected political speech and unlawful foreign Influence Operations look the same, both to a human and to a computer.

Of course, the substance of the message is not the only mechanism for identifying unlawful Influence Operations. The origin of a message, certain artifacts in the digital code, and other forensic methods could distinguish in this fashion. And perhaps implementing those methods would be a worthwhile use of resources.[87] But that analysis misses the critical point of Influence Operations—and indeed of cybersecurity more broadly—adversaries generally do not care how they achieve their goal, only that they do so.

Identifying the source of a substantive message in an Influence Operation is insufficient to prevent the spread of that message, and therefore the impact of the Influence Operation. This is because the message itself becomes protected—even if false or misleading!—as soon as it becomes the opinion of a protected speaker. Quite simply, for a foreign Influence Operation to succeed, all it needs is a given social media platform’s equivalent of resharing by U.S. citizens.[88] Some examples are illustrative:

Thus, to circumvent government-based technological defenses, all an adversary needs to do is get a copy of the message into the public sphere where (mostly unwitting) U.S. citizens will amplify and further distribute the message. Given the inability to distinguish the substance of the message technologically, once its “source” becomes U.S. citizens, the forensic analysis becomes largely irrelevant.

Of course, nothing prevents individual platform owners from moderating content voluntarily. These platforms are, after all, private property—and while certain laws may protect them from liability,[91] and some decisions have limited the authority of government officials to regulate activity in these quasi-public spheres,[92] no statute or court has yet held that these platforms are not the private property of their owners who may choose what speech they wish to permit or prohibit.[93] Indeed, following the events of the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, Twitter elected to “permanently suspend[]” former President Trump’s personal Twitter account.[94]

But applying the debate over platform/content moderation to the issue of unlawful Influence Operations misunderstands the technical challenges involved—as a technological matter, for the reasons discussed above, the only effective means to stop Influence Operations through content moderation requires viewpoint discrimination. Platforms may of course choose to do this, but content moderation requirements by the government simply cannot stop Influence Operations without also suppressing the viewpoints of U.S. citizens.

The examples and discussions in this subsection are only illustrative, of course, and do not cover the full spectrum of possibilities. They are useful tools for understanding the core fundamental problem of using technological solutions to address Influence Operations. Much like those challenges inherent in prior restraint questions under First Amendment doctrine, it is so incredibly difficult to determine a priori what types of technological information are “impermissible” that the risk of over-suppression is substantial (high false positive rate) and the challenges of effective identification are substantial (low true positive and high false negative rates).[95] Furthermore, any attempts to correct these identification errors only will increase the degree to which a centralized authority (whether governmental or private[96]) must engage in mass speech surveillance and moderation.

To the extent that deterrence goals might be achieved by retrospective identification, enforcement, and punishment, the inherent ease with which adversaries can redeploy their assets to jurisdictions outside the reach of civilian law enforcement under international law would suggest general deterrence is unlikely to be effective for stand-alone actors. This is particularly true as the computational science underlying “deep fakes” continues to advance and enables adversaries to create increasingly realistic “false” digital artifacts.[97] Likewise, to the extent such activities are sanctioned, supported, or otherwise tolerated by the foreign jurisdictions in which they occur, the likelihood is very low that those jurisdictions would support the degree of international civilian law enforcement activities by U.S. authorities necessary to achieve general deterrence.

3. Influencing Voter Turnout

Much of the analysis regarding the use of technological solutions for Influence Operations also applies to influencing voter turnout and applies in a similar fashion. There is, however, one corner case of technological problems (and potential solutions) worth examining separately—the dissemination of false information regarding voting procedures.

Most efforts to influence voter turnout are of the same character of persuasive political messaging that characterizes efforts to influence voter ballot choices. The analysis for such messaging is the same in both categories. However, unlike with persuasive messaging regarding policy positions, parties, or candidates, the dissemination of intentionally false information regarding voting procedures may properly be the subject of prohibition.

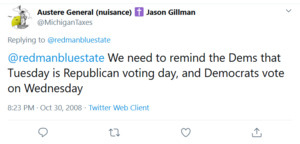

This type of messaging is hardly new. Consider the old joke regarding a flyer posted around town suggesting a “reminder” that voters of a given political party vote on a different day than those of another political party. Such messages have been distributed in paper and electronic form long preceding the 2016 U.S. national election:

While this image likely could be prohibited, whether through direct suppression or criminalization, actions in this regard rarely have been taken.[99] This primarily is for two reasons: (1) the impact scale of such flyers was negligible; and (2) voters generally are thought of as being adequately sophisticated and subject to enough messaging from “trusted” institutional sources,[100] such that they could identify this as false.[101] Remember this latter reasoning—it will become important in the proposals for addressing Influence Operations presented in Part IV.

In the context of internet-enabled Influence Operations, the first condition (de minimis scale of impact) likely no longer is true. Consider what might have been the impact of the mayor’s tweet above. Consider further what might have been the impact of a tweet purportedly from a county elections board, or from a secretary of state or commonwealth. Additionally, the ability of foreign adversaries to selectively customize and target messaging to create confusion has greatly increased. In this regard, the “inefficacy” arguments applicable to the “traditional” physical-world messaging may no longer apply.

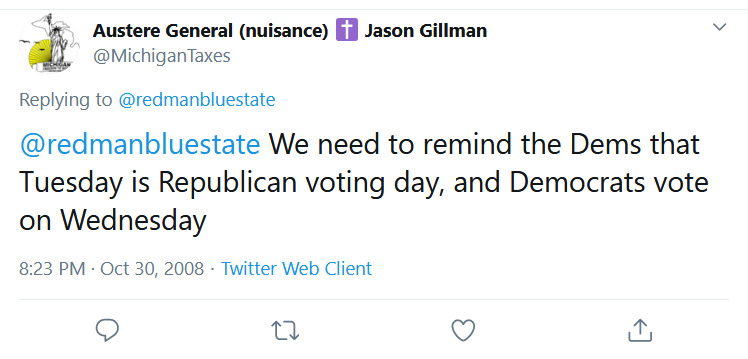

From a technological standpoint, there are some solutions that may be plausible to mitigate the risk of this category of messaging. Certainly, any text-based communications can be scanned, and image-pattern recognition software has advanced adequately such that the text encoded (graphically) in internet meme images also can be reasonably scanned.[102] Nonetheless, even this corner case still is problematic when the source of the disinformation is truly presented as a “joke” or political “opinion”—as in the case of the following social media example:

In this example, it is less clear that this statement could be prohibited by the state. It is clearly made by an individual engaged in political speech against an opposing political party, whom the speaker opposes on the basis of policy reasons.[104] While the underlying message is clearly false (that an opposing political party votes on a different day in a general election), the statement as worded is not easily amenable to criminalization. Proving, for example, that it is not political satire would be difficult as a practical matter. Neither can its “posting” in “public places” be limited via time/place/manner restrictions such as a municipal government might attempt in a town square, because for all social media may operate as such, it remains private property generally beyond the reach of such regulations.[105] It is worth noting, however, that this “private property” character fully permits social media platforms to scan for, identify, and respond to messaging of this type (which is far more deterministic in character than general persuasive political speech and thus much easier to scan for). Indeed, during the 2020 elections, many social media platforms prominently implemented such responses in the form of “tagging” statements about election procedures, integrity, and similar messaging with links to official sources of information.[106]

Lastly, it is worth noting one additional corner case: attempting to influence voter turnout through the seeding of false data related to other factors that indirectly influence turnout. Not all turnout-oriented Influence Operations involve even potentially protected speech. Some involve activities traditionally regarded as potentially criminal “unauthorized access,” such as those involving altering the systems that provide administrative information about polling places, transportation information, weather information, and other data points that have been shown to be able to influence voter turnout.[107] To the extent such information falls into these categories, and not into information attempting to persuade voter turnout based on political claims, legal solutions (classic prohibitions on computer “trespass” and “damage”)[108] clearly are available to help mitigate these risks.

This is a comparatively new area of research—at least from a large-scale empirical perspective—within the context of cybersecurity. It involves approaches such as feeding false or misleading data to systems that provide information regarding topics such as traffic, availability of transportation systems, or weather, in an attempt to have those systems report information not representative of the actual current or likely predicted state of affairs. For example, to alter the Google traffic reports for a given area, one might attach a number of burner phones with Google maps operating to slow-moving drones sufficiently near a major freeway or surface street in the Philadelphia area in an attempt to have those thoroughfares appear to be more clogged than they actually are. Not only might this deter voters (in this case, statistically more likely to be registered Democratic Party voters) from going to the polling places because of high traffic; but further cascade effects might result from the ridesharing services that route their drivers based on data from services like Google’s traffic information system (e.g., Uber) being rerouted to slower/longer routes and increasing actual congestion on those routes that otherwise would be less. The net result could be a decrease in Democratic voter turnout in Philadelphia due to “bad traffic,” something that in a traditional “swing state” like Pennsylvania could have a statistically significant impact on a presidential election under the Electoral College system. To the extent a state like California was close in its overall popular vote, a similar effort could be executed in an area like Orange County to affect registered voters of the Republican Party. Many other examples exist around the United States for both parties, and of course for individual congressional districts. It is currently unclear the extent to which such attacks could be successful, and if so, the degree of difficulty involved in mitigating risks stemming from these attacks.[109]

IV. Palatable Solutions

The problems presented by Influence Operations reach the core of the fundamental challenge in addressing unlawful election interference in a cyber age. When presented with a problem as fundamental as the ability of a foreign adversary to influence the results of a national election, the polity understandably wants swift action and assurances. Assurances not only that future “bad actors” will be punished but perhaps more importantly assurances that future elections are safe and secure. While these well-grounded desires are fundamental to institutions of representative government, it is important to understand that the choices that flow from them must also respect and protect those institutions. Just like a desire for “criminal justice” should not result in ignorance of the “justice” element (i.e., the unjust punishment of a person for a crime of which they are not guilty), a desire for “secure elections” should not undermine the nature of those elections as free.

This Part discusses how the problems raised with election interference in a cyber age force us to revisit a series of well-trodden questions both in law and in computer and information science. It discusses how disambiguating the categories of threats—Election Hacking and Influence Operations—is critical to developing effective solutions. While this Article ultimately concludes that some amount of foreign interference risk must be tolerated, that conclusion does not mean mitigation tools are unavailable. Rather, the critical takeaway is that an era of low-cost information production and information requires both individuals and institutions to educate themselves and be mindful of misinformation—just as voters and institutions have had to do for decades while listening to persuasive messaging of all kinds.

A. A Typology of Solution “Providers”

This Article argues that the field of “election security” generally needs to distinguish between the threats described here as Election Hacking and those described as Influence Operations.[110] This is important for two reasons. First, lumping these two categories together misconstrues them as one challenge solely about the voting process itself. This can lead to misconceptions regarding clear (if difficult) technological solutions, which ignores Influence Operations’ effect on voter behavior. Second, the emotional framing of “hacking” evokes an image of criminal activity that is mismatched with the persuasive argumentation metric and risks promoting approaches seeking to criminalize protected political speech. While a federal constitutional amendment certainly could allow such a policy choice, this Article argues that a reactionary approach of this nature would do more harm than good to political discourse.

Any solution to managing the risk of Influence Operations must necessarily consider the harm that solution may pose to the restriction of protected political speech. Furthermore, this Article argues any such solution should consider the degree to which it impedes or chills[111] political speech. Just because a private actor can restrict speech of a certain type on a social media platform does not mean it is wise, from the viewpoint of democratic discourse, for that platform to do so. Mitigating the risk of Influence Operations must also consider, therefore, which actors should make decisions regarding risk management techniques. Generally speaking, the analysis in this Article suggests three categories of actors: (1) state actors; (2) private-party operators of social media/communications platforms (“platform operators”); and (3) other private individuals.

State actors present a fairly straightforward analysis. As discussed in Parts II and III, with the exception of certain corner cases, the ability of the state to restrict Influence Operations is significantly limited by the confluence of technological limitations and the First Amendment. This is not to say that the Federal Intelligence Community should not attempt to intercept unlawful foreign Influence Operations before they “enter” the U.S. public discourse sphere and become potentially protected political speech. (Indeed, one conclusion of this Article is that significant resources should be devoted to such efforts.) But realistically this will fail to stop a significant portion of such messaging.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, platform operators have come under significant scrutiny in recent years for their efforts—or lack thereof—to combat “misinformation.”[112] It is undeniable that platform operators both have a key role to play in mitigating Influence Operations and that they can do so lawfully in many ways the state cannot. It is also almost certainly the case that the state could not compel platform operators to do so,[113] excepting corner cases discussed in Part II and (perhaps) any content clearly apparent as both unlawful foreign activity and demonstrably false. This leaves an enormous amount of power in the hands of platform operators. Such a result is unusual but not entirely unprecedented or undesirable. After all, an enormous amount of power to influence what information is disseminated in public political discourse has been wielded by traditional news media organizations for decades.

Saying that private individuals bear responsibility for their voting choices is tautological. This is, of course, not to say that foreign influence cannot (or should not) be outlawed. That is a political choice both well within the powers of the federal government and likely within the powers of the states.[114] But ultimately the power to choose how (and whether) to vote is a power reserved exclusively to the polity, and comprises these choices made by individuals. It is anathema to that power and exclusive reservation for any judicial entity to assert that an individual’s choice should be nullified because they were “influenced” by foreign propaganda. That is essentially arguing that affected voters are “too stupid to vote.” Such approaches cannot be the basis for solutions to unlawful foreign Influence Operations.

B. Influence Operation Mitigation: Prescriptions and Proscriptions

Perhaps the most important implication of this Article is that any solution aimed at mitigating the impact of unlawful foreign Influence Operations must balance the risks of not preventing unlawful electoral influence against the dangers inherent in the methods necessary to reduce such influence. While this Article does not purport to offer a comprehensive recommendation for that balance, it does suggest a few prescriptions and proscriptions for the shape of such mitigation efforts.

First, it is critical to distinguish Election Hacking from Influence Operations and not attempt to have the same set of solutions address both. One is an overwhelmingly technological problem that, while it may benefit from legal/regulatory support, focuses primarily on the implementation of technological solutions. By contrast, Influence Operations is a “speech” problem, one mired in technological difficulties even for detection, let alone for mitigation. These two problems require fundamentally different methods of thinking and should not be grouped together.

Second, it is critical to distinguish between problems amenable to legal redress and those not amenable to legal redress. Election Hacking and certain nonspeech (or nonprotected speech) corner cases of Influence Operations involve clearly criminalizable actions for which redress may be available. Examples include cases of record alteration in Election Hacking, and perhaps disenfranchisement through misinformation in corner cases of Influence Operations. Both lie in stark contrast to classic persuasive Influence Operations, in which no disenfranchisement occurred and legal redress is fundamentally improper. We do not have courts reverse or redo election results simply because we think voters may have been “duped” about candidates’ positions.

Third, it is critical to recognize that the core challenge of Influence Operations generally is a speech regulation question. There are, of course, mitigation practices that can be implemented that do not inherently implicate protected speech (e.g., the counterintelligence operations against foreign actors discussed in Part III). But overwhelmingly the problem with Influence Operations is that such activities, well, influence people to vote differently through persuasive political messaging. Which, perhaps obviously, is the zenith of protected speech under U.S. law, at least when disseminated by a protected speaker.[115]

Thus, the fourth point becomes critical—understanding the typology of actors involved in mitigating unlawful Influence Operations—who they are, what they can do, and what affirmative responsibilities they bear. The first category—government actors—clearly has an extremely limited scope within which it can act without violating the First Amendment. In addition to the investigative and counterintelligence activities discussed previously, government actors may also wish to consider the extent to which they participate as speakers. This likely is a necessary and desirable condition as it pertains to administrative information regarding voting procedures, such as times, locations, eligibility requirements, and similar information.

In the context of persuasive messaging regarding substantive policy, however, the role of the government-as-speaker becomes much more complicated. Clearly the government should not be in the business of identifying which policy or political positions are “true.” The more challenging question comes within the context of official government statements regarding the origin of a particular statement, quote, image, video, or other digital artifact. The polity certainly has a strongly arguable right to know whether such artifacts have been identified as unlawfully originating with a foreign actor.[116] But the line between such identification and tagging certain policy positions as “disfavored” (i.e., the result of unlawful foreign influence) is a very narrow one. Often times digital artifacts are nothing more than a visual representation of a generic policy statement (e.g., the examples in Part III). If someone were to redistribute (e.g., “retweet”) such an artifact with their own statement affirming the policy position, should that be branded with an official governmental “seal of disapproval?”

Such an approach raises numerous concerns and is reminiscent of the type of state-sponsored propaganda anathema to the core values of democratic institutions in the United States. There is no clear solution to such a problem, and any line-drawing exercise almost certainly will create advantages for adversaries to develop content pushing just up to (but not crossing) the line. However, information sharing between the government and private platform operators may provide a limited ability to bridge this gap between the intelligence and investigative capabilities of the government and those of platform operations.

Platform operators present perhaps the most promising category of actor for mitigation of Influence Operations. As discussed earlier, this category of private actors is largely free to implement whatever restrictions they deem necessary to the effective operation of their “private property.” Furthermore, they have successfully implemented some “tagging” and “flagging” of information as disputed, unreliable, challenged, or otherwise potentially inaccurate.[117] Such efforts, most predominantly by Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, often come with links to official governmental sources.[118] While “official government sources” are challenging (if not unconstitutional) as pertains to viewpoint-discriminatory policy positions, it clearly is permissible as pertains to the types of administrative information discussed above. Furthermore, nothing prohibits the platform operators themselves, in their capacity as private actors, from pointing to relevant scientific/technical reports produced by government agencies, pointing to official transcripts or records of policy debates by government officials (e.g., congressional floor statements, legislative history, etc.), or pointing to judicial opinions discussing relevant materials. Furthermore, nothing prohibits platform operators from pointing to third-party sources of information they find trustworthy. Little of these approaches are substantively different than what traditional mass media have done for centuries.[119]

Of course, none of this excuses the responsibilities of individuals to become aware of, engaged in, and conversant with the political, social, and other public policy issues that form policy debates in elections. An uninformed electorate absolutely has the right to vote—so-called literacy tests should never return—but that same electorate must take responsibility for its choices and understand that individuals in a society bear a responsibility to one another. Meaningful, respectful, and engaged political messaging and discourse by citizens aimed at educating and persuading their fellow citizens is a necessary element of any response to unlawful foreign Influence Operations.

Finally, regardless of how these questions ultimately are balanced, it is clear that no meaningful system of preventing unlawful electoral interference can operate in silos. Any system must recognize the need for coordination, both among legal and technological institutions, to have any hope of reasonably mitigating risk. To do otherwise, as noted in several places throughout this Article, is to hand adversaries a roadmap for attack. If the 2016 and 2020 U.S. federal elections offer any lesson in this regard, it is that the mere allegation of such interference fundamentally undermines confidence in governmental institutions. That undermining of confidence is a victory for adversaries and is easily achieved if adversaries know or are easily able to infer what vulnerabilities are least well addressed.

Prior work in First Amendment doctrine and political speech is a critical element of any risk calculus regarding the balancing of prevention versus surveillance. The ongoing scholarly and judicial debate regarding the extent to which “more speech” can be the solution to “undesired speech” presents many informative lessons for the electoral interference risk balancing challenge. While the answers may come out differently, at a minimum the structure of the questions is similar and should be thoroughly reexamined within the context of the types of electoral interference most likely in a cyber age. Because, indeed, the most dangerous and effective means of such interference are based on political speech.

V. Conclusion

Election Interference—including both what this Article describes as Election Hacking and as Influence Operations—pose a significant risk to democratic processes and to trust in the institutions of government. It is important first to distinguish between these two categories. This Article analyzes both from a typological standpoint and concludes that the most pressing and difficult challenges result from Influence Operations. Technological solutions have comparatively limited impact on mitigating Influence Operations directly. Ex post legal solutions—typically electoral redress at law—generally are unavailable. And ex ante legal solutions face such significant First Amendment concerns that these solutions could themselves become a form of antidemocratic government influence.

Notwithstanding these challenging typological analyses, this Article suggests several metrics for hope. First, it identifies and cordons off those problems that can be addressed through ex ante technological or legal solutions or through ex post legal redress. Second, considering the success of social media platform operators in responding to misinformation regarding the administrative aspects of the 2020 election and the scientific information regarding COVID-19 vaccines,[120] it becomes clear that there is space for platform operators—who are private actors—to implement some types of counter-messaging designed to identify misinformation or misrepresentation resulting from unlawful foreign Influence Operations. This must, of course, be balanced against the risks of becoming disproportionate influencers themselves, but centuries of a free press in the United States have demonstrated that our legal institutions and a free, competitive, and open media market can balance these concerns. Lastly, we must never forget that no law or technology can serve as a substitute for an engaged, respectful, and persuasive political discourse among the polity.

See generally Lee C. Bollinger & Michael A. McRobbie, Securing the Vote: Protecting American Democracy (2018); Defending Against Election Interference Before the Subcomm. on Cybersecurity, Infrastructure Protection, and Innovation of the H. Comm. on Homeland Sec., 116th Cong. (2019) [hereinafter Defending Against Election Interference] (statement of Matt Blaze, Professor and McDevitt Chair of Computer Science and Law, Georgetown University).

See generally Bollinger & McRobbie, supra note 1; Defending Against Election Interference, supra note 1.

Bollinger & McRobbie, supra note 1 at 83, 100–01.

Id. at 36, 110–11.

Id. at 36, 62, 112.

See Thomas B. Edsall, Opinion, How Many People Support Trump but Don’t Want to Admit It?, N.Y. Times (May 11, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/11/opinion/campaign-stops/how-many-people-support-trump-but-dont-want-to-admit-it.html [https://per

ma.cc/7HGQ-NG5A]; Paul Steinhauser, What the Polls and Pundits Got Wrong: Trump Outperforms Predictions Again, Fox News (Nov. 4, 2020, 10:02 AM), https://www.foxnews.com/politics/what-the-polls-and-pundits-got-wrong-trump-outperforms-predictions-again [https://perma.cc/VQ8Z-H4XM]; Caleb Parke, 'Trump Agenda Won Up and Down the Ballot" as Pundits and Polls Missed the Mark Again: Kellyanne Conway, Fox News (Nov. 5, 2020, 12:16 PM), https://www.foxnews.com/politics/2020-election-polls-race-trump-results-kellyanne-conway [https://perma.cc/EF65-LM4P]. But see, e.g., Pew Rsch. Ctr., For Most Trump Voters, ‘Very Warm’ Feelings for Him Endured 4, 12 (Aug. 9, 2018) [hereinafter For Most Trump Voters], https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/08/8-9-2018-Validated-voters-release-with-10-2-19-and-10-17-18-corrections.pdf [https://perma.cc/N6C8-J4W5] (noting that among the approximately one-third of the electorate with mixed political ideology, President Trump was favored 48% to 42% over Secretary Clinton and noting generally that the overwhelming majority of those reporting voting for President Trump in 2016 maintained favorable views of him in 2018).

See generally 1 Robert S. Mueller, III, Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election (2019) [hereinafter Mueller Report].

See generally Nat’l Intel. Council, Foreign Threats to the 2020 US Federal Elections (2021), https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ICA-declass-16MAR21.pdf [https://perma.cc/W7XH-QQAJ]. The Author takes no position whether additional information exists, other than to note that from a historical perspective, law enforcement and intelligence assessments become public over time consistent with applicable law, national security, and prosecutorial goals, and if any additional information exists, it could be revealed after publication of this Article.

See, e.g., 52 U.S.C. § 30121 (citing § 30104(f)(3)).

G.A. Res. 48/124, at 2 (Feb. 14, 1994).

See Aaron Rupar, The White House Says Russia Didn’t Impact the 2016 Election. That’s Not Exactly True, Vox (July 26, 2019, 4:40 PM), https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/7/26/8931950/trump-russia-meddling-mueller-gidley-no-impact [https://perma.cc/8DQ9-G9UG]; Gustavo López & Antonio Flores, Dislike of Candidates or Campaign Issues Was Most Common Reason for Not Voting in 2016, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (June 1, 2017), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/06/01/dislike-of-candidates-or-campaign-issues-was-most-common-reason-for-not-voting-in-2016/ [https://perma.cc/F27M-27XU]; For Most Trump Voters, supra note 6.

The scope and scale of national campaigns are typical examples of lawful efforts to persuade voters. Those instances where legal limitations on the method or funding of campaigning have been implemented, enforced, or legally challenged are typical examples of potentially unlawful efforts. See, e.g., Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 26–27, 192 (1976); Citizens United v. Fed. Election Comm’n, 558 U.S. 310, 314, 356 (2010). This is also true for almost any foreign efforts to interfere in U.S. elections. See, e.g., 52 U.S.C. § 30121 (“It shall be unlawful for a foreign national . . . to make a contribution or donation of money or other thing of value . . . in connection with a Federal, State, or local election.”).

As noted by many leading researchers, so-called online voting (e.g., internet-, app-, or web-based voting) presents a host of problems that are much more challenging to solve than those involved in managing security risks for traditional election systems maintained for in-person and postal-mail voting systems. See Bollinger & McRobbie, supra note 1, at 61, 68, 101, 106; see also Defending Against Election Interference, supra note 1, at 11, 14.

Consider, for example, the efforts of social media companies Twitter and Facebook during the months leading up to the 2020 election in creating a dedicated and prominent “flagging” system for (what they identified as) potentially misleading statements regarding the election and providing links to official election information sources. See Shannon Bond, Twitter Expands Warning Labels to Slow Spread of Election Misinformation, NPR (Oct. 9, 2020, 12:00 PM), https://www.npr.org/2020/10/09/922028482/twitter-expands-warning-labels-to-slow-spread-of-election-misinformation [https://perma.cc/L77H-CJED]; Danielle Abril, Facebook Reveals that Massive Amounts of Misinformation Flooded Its Service During the Election, Fortune (Nov. 19, 2020, 1:49 PM), https://fortune.com/2020/11/19/facebook-misinformation-labeled-180-million-posts-2020-election-hate-speech-prevalence/ [https://perma.cc/2UBJ-9DMJ] (“Facebook added warning labels to more than 180 million posts that included election misinformation between March and Nov. 3.”); Twitter Civic Integrity Policy, Twitter (Oct. 2021), https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/election-integrity-policy [https://perma.cc/TZC4-W6N6]; Facebook Community Standards, Meta, https://transparency.fb.com/policies/community-standards/ [https://perma.cc/WF7X-4C47] (last visited Feb. 2, 2022).

See, e.g., Assemb. B. 1104, 2017–18 Sess. (Cal. 2017) (codified as amended at Cal. Elec. Code § 18320).

Lucan Ahmad Way & Adam Casey, Russia Has Been Meddling in Foreign Elections for Decades. Has It Made a Difference?, Wash. Post (Jan. 8, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/01/05/russia-has-been-meddling-in-foreign-elections-for-decades-has-it-made-a-difference/ [https://perma.cc/JVC2-BHVZ]; see also Adam Casey & Lucan Ahmad Way, Russian Electoral Interventions, 1991-2017, U. Toronto Dataverse (2017), https://dataverse.scholarsportal.info/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.5683/SP/BYRQQS [https://perma.cc/2AJE-6CT9]; Dov H. Levin, When the Great Power Gets a Vote: The Effects of Great Power Electoral Interventions on Election Results, 60 Int’l Stud. Q. 189, 192 (2016).

It is worth noting that similar arguments might apply to the 2016 “Brexit” national referendum in the United Kingdom, however, discussion of non-U.S. examples is outside the scope of this Article. See Carole Cadwalladr, The Great British Brexit Robbery: How Our Democracy Was Hijacked, Guardian (May 7, 2017, 4:00 AM), https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/07/the-great-british-brexit-robbery-hijacked-democracy [https://perma.cc/K2PH-947G].

Id.; Partisanship and Political Animosity in 2016, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (June 22, 2016), https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2016/06/22/partisanship-and-political-animosity-in-2016/ [https://perma.cc/753E-Z8XL]; Way & Casey, supra note 16; Harlan Ullman, Would Things Really Be Any Different if Hillary Clinton Were President?, Observer (Dec. 27, 2017, 7:30 AM), https://observer.com/2017/12/would-things-really-be-any-different-if-hillary-clinton-were-president/ [https://perma.cc/8QBF-5D8D].

The margin of victory is the total number of votes that would need to shift to alter the result of the presidential election. Due to the nature of the electoral college system, shifting a total of 77,774 votes across three states—Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—would have resulted in a change in the electoral outcome. See Eileen J. Leamon & Jason Bucelato, Federal Elections 2016: Election Results for the U.S. President, the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives, Fed. Election Comm’n. (Dec. 2017), https://www.fec.gov/resources/cms-content/documents/federalelections2016.pdf [https://perma.cc/MC7E-CWP9] (reporting the official results of the 2016 U.S. presidential election as relevant to the calculations noted here). A 77,744-vote difference represents approximately 0.057% of the total overall votes cast and is approximately thirty-six times less than the difference in the popular vote, which favored the losing candidate. Id. Regardless of the virtues or drawbacks of the electoral college system, these statistics paint a stark picture in the context of electoral interference—one in which a small amount of influence could well alter the course of a nation’s history for many years.

Similar allegations have been made regarding the “Brexit” referendum. See Cadwalladr, supra note 17. While there are several similarities, the fundamental distinctions between a nation referendum (via pure majority count) and a national election through an electoral college system suggest that while informative, the strategic analysis may itself not translate. EU Referendum Results, BBC, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/politics/eu_referendum/results [https://perma.cc/3ELS-4JTU] (last visited Feb. 25, 2022) (showing that a pure majority—51.9%—was sufficient in the Brexit referendum for the “Leave” vote to succeed). For these and related reasons, the summer 2016 U.K. “Brexit” referendum is excluded for these purposes.

See supra notes 1, 7, 16, 17.

“Attack surface” is a term in cybersecurity describing an aspect, technological, human, or otherwise, of a system that creates potential for an adversary to attempt to compromise that system.

“Insider threat(s)” (e.g., unlawful action by election officials or law enforcement officers) and internal influence generally are outside the scope of this Article. This category represents a structurally different problem than foreign influence and is easily redressable upon detection.

Influence Operations also is a term of art within the intelligence communities and within international public policy and related subdisciplines. See, e.g., Information Operations, Rand Corp., https://www.rand.org/topics/information-operations.html [https://perma.cc/S9QY-BP6F] (last visited Jan. 29, 2022).

Legal mitigation, deterrence, and redress refer to mechanisms based on statutory frameworks and legal institutions as the mechanisms for achieving these goals (such as the state or federal courts), as distinct from political mechanisms and institutions (such as the county and state election officials, the Electoral College, and the U.S. Congress).

Incidental, second-order voter persuasion may occur as a result of Election Hacking, primarily in the form of individuals losing confidence in election institutions. Stephanie Kulke, 38% of Americans Lack Confidence in Election Fairness, Northwestern: Nw. Now (Dec. 23, 2020), https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2020/12/38-of-americans-lack-confidence-in-election-fairness/ [https://perma.cc/JHB7-TVAX]. The consideration of targeted efforts in this regard is outside the scope of this paper, primarily because it is extremely difficult at this time to target such efforts at a specific candidate, as opposed to promoting general institutional mistrust (the electoral impact of which is difficult to predict).

Substantial credit for the framing of this argument is owed to Joseph Lorenzo Hall, who convinced the author of the necessity of making this point so bluntly. See David Thaw (@dbthaw), Twitter (Jan. 30, 2019, 2:16 PM), https://twitter.com/dbthaw/status/1090705314029191172 [https://perma.cc/WN7B-GB36].

See generally Bollinger & McRobbie, ch. 5, supra note 1.

See id.

See Bernd Beber & Alexandra Scacco, What the Numbers Say: A Digit-Based Test for Election Fraud, 20 Pol. Analysis 211, 222 (2012), https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/AD86EEBC2F199E2C8A2FD36BD3799DF9/S1047198700013103a.pdf/ [https://perma.cc/7AXM-T5HN].

Alan Blinder, New Election Ordered in North Carolina Race at Center of Fraud Inquiry, N.Y. Times (Feb. 21, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/21/us/mark-harris-nc-voter-fraud.html [https://perma.cc/V9G9-S7FU]. This Article was written before sufficient raw evidence was publicly available to evaluate independently whether such activities occurred during the 2020 election cycle but notes that key federal election security officials released formal statements in November 2020 regarding their belief that no compromise of election systems occurred. Statement from CISA Director Krebs Following Final Day of Voting, Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Agency (Nov. 2, 2021) [hereinafter Statement from CISA Director Krebs], https://www.cisa.gov/news/2020/11/04/statement-cisa-director-krebs-following-final-day-voting [https://perma.cc/QYD3-ZNYM] (“[CISA had] no evidence any foreign adversary was capable of preventing Americans from voting or changing vote tallies.”); Joint Statement from Elections Infrastructure Government Coordinating Council & the Election Infrastructure Sector Coordinating Executive Committees, Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Agency (Nov. 12, 2020) [hereinafter Election Infrastructure Council Joint Statement], https://www.cisa.gov/news/2020/11/12/joint-statement-elections-infrastructure-government-coordinating-council-election [https://perma.cc/4ZDF-CEQ3] (“The November 3rd election was the most secure in American history . . . . There [was] no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised.”); see also Nat’l Intel. Council, supra note 8, at 1–2.

For further discussion of the large-scale/low-marginal cost dilemma, see infra Section III.A.

See generally Blake E. Strom et al., MITRE ATT&CK: Design and Philosophy, MITRE (Mar. 2020), https://attack.mitre.org/docs/ATTACK_Design_and_Philosophy_March_2020.pdf [https://perma.cc/3CDY-63PS]; MITRE ATT&CK, https://attack.mitre.org/ [https://perma.cc/P3NC-SM44] (last visited Feb. 2, 2022).

See Bollinger & McRobbie, ch. 5, supra note 1; Defending Against Election Interference, supra note 1.

See Defending Against Election Interference, supra note 1.

See id.

See id. at 13–15.

Many such confirmations were by politically appointed federal officials in the administration that lost the 2020 presidential election or state officials of the political party that lost that presidential election. Given the party affiliation of these individuals, it is reasonable to assume that if election infrastructure compromise existed, they would be incentivized to find it (rather than incentivized to hide or ignore it), thus lending further credence to the position that no such evidence of compromise had been found. (This Article takes no position regarding whether such officials actually had any such incentive or motivation, only that to the extent any such incentives were to exist, the resultant statements would be contrary to such incentives or motivations).

See, e.g., Statement from CISA Director Krebs, supra note 31; Election Infrastructure Council Joint Statement, supra note 31; 2020 Texas Election Security Update, Tex. Sec’y of State John B. Scott, https://www.sos.state.tx.us/elections/conducting/security-update.shtml [https://perma.cc/TGY8-RWRK] (last visited Mar. 31, 2022); Colo. Sec’y of State Jena Griswold, Election Integrity and Security, https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/ElectionIntegrity/index.html [https://perma.cc/MK7V-XXNP] (last visited Mar. 31, 2022).

See, e.g., Blinder, supra note 31.

See Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437 (1965) (codified as amended at 52 U.S.C. §§ 10303, 10306, 10503); Joshua A. Douglas, The Right to Vote Under Local Law, 85 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1039, 1046 (2017).

See 52 U.S.C. § 10307(b).

These certainly would be highly contentious political questions (and, indeed, as of the time of writing of this Article, several state legislatures have considered new and controversial legislation limiting, for example, postal mail-based voting), but that is the key—they are political questions. Such questions are capable of being resolved through a constitutionally permissible process of policymaking and subject to constitutional judicial oversight. Regardless of whether anyone agrees with a particular policy, such policies do not inherently conflict with other constitutional principles as do redress or prevention mechanisms for Influence Operations.

E.g., 52 U.S.C. § 10307(c)).

See Shelby Cnty. v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529, 535, 538–39 (2013) (noting the exceptional nature of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, its limited duration, and ongoing consideration by Congress for renewal).

Elections to determine the legitimacy of elections, while theoretically possible, are mathematically undifferentiable from a single election—in the end, they all (mathematically) reduce to an expression of the political will of the voters according to a predetermined set of rules. Adding more rules or steps does not change the fundamental fact that the method of influence remains an election and that influence can be exerted upon an election.