- I. Identifying the Current Cliques: Collaboration Between Schools, Healthcare Providers, and Lawyers

- II. Making New Friends: How and Why SBMLPs Expand the Scope of MLP Collaboration

- III. Overcoming the Drama: Navigating Privacy and Ethics Laws

- A. Data Privacy: Laws That May Prevent Health Care Providers and School Partners from Sharing Data with Attorneys

- B. Legal Ethics: How SBMLP Lawyers Can Protect Their Clients’ Information in Multidisciplinary Partnerships

- 1. Professional Independence: How Attorneys Can Navigate the Delicate School-to-Attorney Relationship.

- 2. Client Confidentiality: Collaboration Does Not Inevitably Infringe on Confidentiality.

- 3. Attorney–Client Privilege: Weighing the Risk of Waiver Against the Rewards of Collaboration.

- 4. Legal Ethics: Conclusion.

- IV. Conclusion

Joe looks unusually tired this week, his teacher thinks as she passes by his desk, noting the dark circles under his eyes. After class, she pulls him aside and suggests that he go to the school‑based health center for a chat with the pediatrician. Joe walks down the hall to the health center, where he fills out a questionnaire. The questions are unusual for a health visit—asking whether he was cold last night, when he last went without a meal, how many hours he slept the night before, and whether he has noticed any chipped paint at home. Finally, the pediatrician calls him to the back office.

When she asks him about the responses to one of the questions on the form, he reluctantly admits that he has been sleeping (or, more accurately, trying to sleep) on his uncle’s couch because the electricity was shut off at his mom’s house last week. He can’t do his homework in the evenings without the light, but he is worried about his mom. The pediatrician asks if she can refer him to the on-site attorney, Mr. Kay, for help. Joe agrees.

Joe is a little embarrassed to talk about his situation with another person, but he knows Mr. Kay. As the on-site attorney at the school-based medical–legal partnership, Mr. Kay regularly sits with students at lunchtime. After interviewing Joe and getting his consent to speak to his mother, Mr. Kay uses affidavits from school staff and the pediatrician to support Joe’s mom in an application for emergency utility assistance and debt forgiveness on past utility bills.[1]

The ending to Joe’s story depends on a series of insights and referrals, each requiring Joe to choose and follow through on the next step. When each step is co-located, integrated, and familiar, students like Joe are much more likely to get help.[2] But most students are not as lucky as Joe. Many students will need to travel across town, interact with strangers, and unravel a maze of referral requirements to access the help that Joe received. Some lawyers and doctors, the architects behind the school-based medical–legal partnership (SBMLP) movement, are trying to make more stories end like Joe’s.

The medical–legal partnership (MLP), a collaborative health and legal services delivery model, has rapidly expanded over the past decade.[3] Recognizing the way that societal forces frame health, insurance policies and healthcare laws are incentivizing an expansion of multidisciplinary partnerships and a focus on the “Social Determinants of Health” (SDOH)—the social factors like race, socioeconomic status, environment, education level, and political forces that have a profound impact on an individual’s chronic health.[4] As national dialogue continues regarding criminal justice reform[5] and racial disparities in chronic health outcomes,[6] some legal, health, and education professionals are joining forces at a place where many of the SDOH collide: public schools.

This burgeoning partnership model is fragile.[7] As school administrators, healthcare professionals, and attorneys implement the MLP model in a new frontier, they must navigate the data privacy laws and legal ethics rules that the model implicates.[8] This Comment seeks to assist current and aspiring SBMLP practitioners by identifying, analyzing, and providing recommendations to mitigate the legal and ethical risks the model presents.

This Comment has three parts. Part I unpacks the status quo by first considering the reasons behind a resurgence in school‑based legal services and healthcare services before explaining the mechanics of MLPs. Part II presents the SBMLP model and briefly discusses the existing SBMLPs. Part II also considers the rewards that SBMLPs offer each stakeholder. Finally, Part III identifies, analyzes, and recommends ways to navigate the data privacy and legal ethics issues that are hindering the large-scale adoption and expansion of SBMLPs.

I. Identifying the Current Cliques: Collaboration Between Schools, Healthcare Providers, and Lawyers

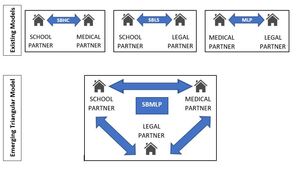

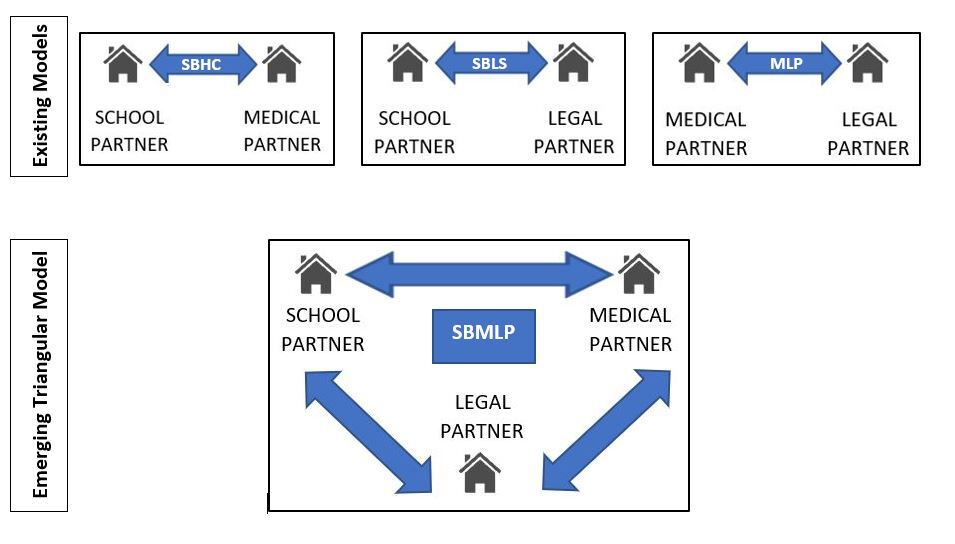

Collaboration between schools, healthcare providers, and lawyers is not necessarily new. Linear collaborative frameworks exist between schools and healthcare providers (operating as school-based health centers or SBHCs), healthcare providers and attorneys (operating as medical–legal partnerships or MLPs) and, to a lesser extent, attorneys and schools (operating as school-based legal services or SBLS).[9] School-based MLPs (SBMLPs) merge the linear partnership models to form a triangular relationship between schools, healthcare providers, and attorneys.[10]

This Part first unpacks the status quo models and the unique challenges that collaboration in these existing contexts can present before exploring the added complexity that the triangular SBMLP model introduces.

A. What Is Happening in the Schools? The Services Silos of SBHCs and SBLS

Many public schools already partner with community health centers or legal services providers. However, the two “status-quo,” siloed delivery models—SBHCs and SBLS—are not responsive to shifting policy priorities and social needs.[12] First, a significant population of low-income parents (and guardians of minor children) are not seeking or receiving legal aid to navigate civil legal problems.[13] Second, policymakers and education administrators have implemented numerous policies, programs, and funding incentives to encourage schools to establish multidisciplinary partnerships with community-based social services organizations, such as health clinics.[14] These initiatives are driven by a recognition that nonacademic issues—like access to healthcare, undiagnosed behavioral health ailments, homelessness or housing insecurity, and hunger—heavily impact students’ academic success.[15] While offering part of the solution, the siloed services that SBLS and SBHCs offer are an incomplete response to these phenomena.

1. School-Based Legal Services (SBLS).

SBLS is a legal services delivery model, typically located within a predominantly low-income community school, that provides services to families on matters like “housing, employment, consumer, domestic violence, immigration, public benefits, and family law.”[16] SBLS might also engage in legal education efforts, engaging parents and students in trainings and workshops to aid them in independently navigating the legal system.[17]

SBLS have deep roots in U.S. public schools.[18] During the Depression, it was common for public schools to incorporate space for health clinics, employment resource centers, and legal aid clinics.[19] After the Depression, SBLS largely disappeared until progressive lawyers in the 1960s brought a brief resurgence.[20] The so-called poverty lawyers who emerged from the Civil Rights Era emphasized neighborhood-based legal services and, by consequence, reentered community schools.[21] While the importance of integrating legal services into community spaces that are readily accessible to at-risk and low-income clients is still acknowledged today, intraorganizational conflicts, funding shortages, and overwhelming need plague the effort to provide holistic legal services in schools.[22]

2. School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs).

Typically located physically on a school’s grounds, SBHCs provide healthcare services varying from only primary care to primary, dental, vision, and behavioral health services.[23] There is no uniform definition of the specific staffing or services required to qualify as an SBHC.[24] The National School-Based Health Alliance reports that 85% of SBHCs retain a nurse practitioner, 40% include a designated physician, and 20% employ at least one physician assistant.[25] More than half of SBHCs employ both primary care and behavioral health providers.[26] According to the most recent National School‑Based Health Care Census, 6.3 million students receive services from SBHCs in 10,629 public schools—or “13% of school‑age youth in approximately 10% of US public schools.”[27] While SBHCs are a great achievement in the direction of addressing SDOH, collaboration between lawyers and healthcare providers is necessary because, while medical providers are often quick to note SDOH, they lack the training and resources to address the corresponding legal issues that shape a patient’s poor health condition.[28]

B. What Is Happening in Healthcare? MLPs Expanding the Collaborative Frontier for Lawyers

MLPs are a collaborative legal- and medical-services delivery model where attorneys and healthcare providers work together to screen for and treat social and environmentally driven health needs (like insurance, public benefits, housing, education, employment, legal status, and safety), in addition to traditional physical and behavioral health needs.[29]

MLPs, which began less than three decades ago, have rapidly expanded in response to a few factors. First, a shift in Medicaid payment models incentivized collaboration between healthcare professionals and community organizations.[30] Second, a growing body within the medical profession (which is supported by policy reforms in Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act) called for an emphasis on service delivery focused on the social determinants of health (SDOH).[31] These forces led to an increase in clinical health providers partnering with social services organizations, screening for social (in addition to medical) risks, and measuring success by SDOH metrics.[32] The medical community is enforcing this new focus on SDOH at the earliest stage of a physician’s education; Association of American Medical Colleges announced in 2015 that the MCAT will now test medical-school applicants on SDOH issues.[33]

MLPs are typically located in a hospital or community health clinic and draw on “an interprofessional team to improve the health and wellbeing of low-income and other vulnerable populations by addressing unmet legal needs and removing legal barriers that impede access to [health] care.”[34] MLP lawyers avoid litigation when possible, instead focusing on preventative law, while engaging social workers and other community stakeholders.[35]

MLPs respond to the growing recognition that an individual’s health is overwhelmingly impacted and determined by social, economic, and environmental conditions, or SDOH, which traditional healthcare delivery models have historically overlooked.[36] Conditions such as an individual’s “income and wealth, family and household structure, social support and isolation, education, occupation, discrimination, neighborhood conditions, and social institutions” shape a person’s health because those conditions create norms and opportunities to engage in healthy habits and enable or restrain a person’s access to traditional medical care.[37]

The first MLP started in 1993 with a partnership between one lawyer and the Boston Medical Center.[38] In 2018, there were 330 active MLPs in hospitals and health clinics across forty-six states.[39] By 2020, the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership reported an increase to 450 active MLPs in forty-nine states.[40] The National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership categorizes the common structures into three groups: (1) Referral Networks, (2) Coordinating Staff, and (3) One Organization.[41]

Operationally, a referral network funnels all communication through the patient.[43] Because partners rely on the patient to enable collaboration, this model is the least integrated.[44] To facilitate the partnership, medical partners will screen for potential legal issues and refer patients to an attorney partner.[45] The medical partner may share the attorney’s contact information with the patient but will not communicate directly with the attorney on behalf of the patient.[46] The patient must initiate communication and transfer any needed health information to the attorney partner because this model does not allow direct communication between the health and legal partner.[47]

The second model, coordinating staff, is slightly more integrated—and more likely to result in a patient obtaining legal services—than a referral network.[49] This model employs staff specifically responsible for sharing information between the medical and legal partners.[50] These staff are often trained in areas that complement the goals of the partnership, like social work or case management.[51] Because this model is not reliant on the patient to transfer information, staff must obtain the necessary patient consent.[52]

In a fully integrated “one organization” MLP model, the same organization employs the medical and legal partners.[54] Practitioners collaborate through intentional co-locating and, sometimes, by sharing data management systems to track health and legal information.[55] Patients encountering this model are consistently screened for “health-harming legal needs” (informed by the SDOH) and receive at least some regular, on-site legal assistance.[56]

Many scholars have explored the challenges that data privacy laws and legal ethics rules pose for the long-term success of collaboration between healthcare and legal professionals forming MLPs.[57] But few, if any, have explored the challenges posed by the addition of a new partner: the community school. These hurdles and potential solutions are discussed in Part III, after first pausing in Part II to unpack what an SBMLP is and why the various partners might be inclined to participate.

II. Making New Friends: How and Why SBMLPs Expand the Scope of MLP Collaboration

The school-based medical–legal partnership (SBMLP) model builds on the strengths of the models discussed in the previous Part to facilitate a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to addressing the social determinants of health (SDOH) of high-risk school-aged youth. SBMLPs move the collaboration out of the hospital or clinical setting and into schools.[58]

Though SBMLP models are still in infancy,[59] the concept aligns with the roots of medical–legal partnerships (MLPs), which were initially focused on pediatric care and drew on the understanding that “the more significant the cumulative material hardships, the more likely children are to be . . . at risk of developmental delays.”[60]

The “[k]ey [c]haracteristics” of an SBMLP are:

(1) provid[ing] quality, compressive healthcare services that help students thrive in school and life[;] (2) locat[ing] in or near a school facility and open during school hours[;] (3) organiz[ing] through school, community, and health provider relationships[;] (4) staff[ing] by qualified health professionals[;] and (5) focus[ing] on the prevention, early identification, and treatment of medical and behavioral concerns that can interfere with a student’s learning.[61]

As research has documented the long-term health impacts of youth incarceration, often initiated by a child’s first encounter with school disciplinary proceedings,[62] healthcare and legal professionals have found a common interest in public schools.[63]

A. How It Works: Examples of the Few Existing SBMLPs

According to the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnerships, there are two SBMLPs currently in practice: Erie Family Health Centers (Erie) in Chicago, Illinois, and Georgetown University Health Justice Alliance (HJA) in Washington, D.C.[64] In researching for this Comment, I found another group that aspires to become an SBMLP: People’s Community Clinic (PCC), a federally qualified health center, has a school-based clinic and is in the process of expanding its MLP to include legal services at a neighboring school’s clinic.[65]

Both Erie and HJA are referral-based partnerships between existing school-based healthcare centers (SBHCs) and outside attorneys (either at a law school or local legal aid).[66] These two SBMLPs are relatively traditional in their collaboration, neither co-locating with the attorneys nor sharing electronic health data with attorneys without a specific request related to client representation and a client’s written consent.[67] Despite not co‑locating, these clinics harness many of the benefits of collaboration through targeted screening tools for health-harming legal needs that the SBHC integrates into its clinical intake flow.[68]

Both Erie and HJA decline to represent children clients in education-related legal matters that are adversarial to the school partners, out of respect for the need to foster trust with the school partner.[69] Instead, both SBMLPs respond to students’ requests for education-related advocacy by facilitating a referral for services outside of the SBMLP.[70] Erie has used its relationships with children to assist them in sensitive, reproductive health proceedings before state judges and to lead advocacy efforts to expand social services for homeless minors in Illinois.[71] Both SBMLPs primarily focus on addressing legal issues that impact students’ families, like guardianship, health and food benefits, landlord tenant disputes, and education resources.[72] To respond most effectively to identified community needs, HJA refined its screening tool to focus on these areas: “inadequate access to public benefits and healthcare; unstable housing and poor housing conditions; educational struggles including suspension/expulsion, lack of access to educational supports, and bullying; living with a non-parent caregiver; and teen pregnancy and parenting issues.”[73]

PCC’s MLP seeks to build a collaborative and integrated SBMLP.[74] The healthcare providers and attorney for PCC’s MLP are co-located in a clinic just across from a middle school.[75] The MLP had plans to form a partnership with the school district in 2020; however, the COVID-19 pandemic made relationship building challenging.[76] Currently, PCC’s MLP focuses on three legal practices: “special education/disciplinary proceedings, guardianship and alternatives to guardianship, and disability appeals/benefits.”[77] While PCC’s MLP has represented children in a few cases involving school discipline and bullying, it primarily avoids criminal law.[78] The school does not currently share data with either the health center or attorney.[79] The health clinic does share aggregate data “with the school regarding monthly encounters (visits), patients by age, and patients by school campus.”[80] PCC’s MLP hopes to someday receive access to data regarding grades, absences, and other school records.[81] However, the MLP partners share electronic information, which allows MLP attorneys to access electronic health records and provide legal updates to health clinicians.[82]

Overall, PCC has one of the most integrated MLPs, built on the idea that collaboration is more effective in meeting the multifaceted needs of vulnerable children and their families when practitioners offer integrated services in the same location.[83] Co‑locating increases the likelihood that a client will access services because it eliminates travel barriers.[84] Co-locating also increases the likelihood that medical and legal practitioners will engage in regular communication and take an interdisciplinary approach to addressing health needs.[85] PCC attorneys believe that concerns about the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), and the generally untested nature of the MLP in a school-based context, may prevent the school from moving beyond a referral-based relationship.[86]

B. Winning Over Reluctant Rivalries: Why a Collaborative Approach Already Makes Sense for Schools, Attorneys, and Healthcare Providers

Before turning in Part III to the risks and challenges associated with the collaborative SBMLP model, it is worth considering the ways that the model benefits schools, healthcare professionals, and lawyers and why those benefits likely outweigh the underlying risks.

One benefit that schools would receive by collaborating with an SBMLP is a reduction of liability and adversarial special education proceedings. School administrators may be understandably reluctant to partner with attorneys; the first MLPs also faced resistance from doctors worried about legal partnerships causing an increase in malpractice claims.[87] But the expansion of MLPs around the country indicates that those fears have mostly dissipated as the common goal of providing comprehensive holistic care took precedent for practitioners operating MLPs.[88] Likewise, attorneys partnering with schools through existing SBMLPs are so concerned with preserving a collegial relationship that they outsource any special education claims that arise from the SBMLP.[89] An open portal of communication between the school, healthcare provider, and attorney could allow the schools to better anticipate, assess, and respond to adversarial claims, whether filed internally through the SBMLP attorney or referred externally. While school administrators may not be eager to modify educational services, anticipating and appropriately responding to requests from trusted partners, instead of adversaries, could decrease the school system’s overall liability and reduce the risk of costly litigation and settlements.[90]

A second, more intuitive benefit that educators will receive through collaboration is a more stable, healthy, and—by extension—academically successful student body.[91] For schools already participating in an SBHC, attorneys can expand impact beyond the healthcare professionals’ realm of influence, like unsafe lead levels in public housing or hunger caused by inability to access available benefits.[92] For instance, a teacher may notice a student’s frequent coughing, and a health center may prescribe treatment for asthma, but if the child lives in housing with mold and mildew, she may not respond to treatment without legal advocacy to compel her landlord to remediate the harmful conditions.[93]

For attorneys, SBMLPs are part of a larger movement toward holistic delivery of legal services, focused on addressing the overall social and health needs underlying access to justice issues.[94] Attorneys already rely on healthcare professionals to provide behavioral health referrals and health impairment documentation in support of applications for children seeking special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.[95] School professionals and teachers—who interact with children regularly—are in the best position to perceive children’s legal needs, like housing insecurity, hunger, immigration issues, or access to mental health services.[96]

As discussed in section I.B, politicians and insurance providers are incentivizing healthcare providers to address SDOH and engage with community partners, which the SBMLP model embodies.[97] Healthcare providers are likely to be the most enthusiastic partners, as SBMLPs align with their longstanding commitment to school health (see SBHC discussion in section II.A.2) and the collaborative, multidisciplinary MLP movement.

While partners and communities can greatly benefit from SBMLPs, there are a number of risks that may make potential partners reluctant to collaborate. The next Part explores the data privacy and legal ethics issues that aspiring SBMLP practitioners will need to navigate.

III. Overcoming the Drama: Navigating Privacy and Ethics Laws

Frequent, open communication and agreement of guiding principles are essential keys to successful partnerships.[98] To SBMLPs, these aspirations implicate a slew of potential hurdles to the model’s long-term success and expansion. For instance, state and federal laws governing privacy for students and patients may make it difficult to enable collaboration between partners.[99] Additionally, school administrators, lawyers, and healthcare professionals must navigate the inevitable clash of three different ethical codes.[100]

A. Data Privacy: Laws That May Prevent Health Care Providers and School Partners from Sharing Data with Attorneys

Traditional MLPs implicate data privacy concerns, specifically pertaining to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).[101] Expanding the partnership to include schools adds a layer of complexity, as practitioners will also need to navigate the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).[102] Usually, information that a school-based health center (SBHC) keeps would not be part of a student’s education record, implicating FERPA, but would solely be subject to HIPAA.[103] However, if a school nurse maintains the records, they may also trigger FERPA protections.[104] Practitioners seeking to forge this multidisciplinary trail must distinguish the overlaps and unique requirements of these privacy laws.

1. HIPAA Compliance Requirements for Healthcare Partners.

HIPAA prohibits unauthorized disclosure of patients’ “protected health information” (PHI), or health information that is “individually identifiable.”[105] The limited exceptions to the nondisclosure requirement are: treatment, payment, or healthcare operations.[106] HIPAA is applicable to all forms of communication concerning protected health information, irrespective of the medium of communication used.[107] Whether an SBMLP operates as a strictly referral network or a fully integrated organization network,[108] the care coordination will likely require patient authorization.[109]

Under HIPAA, proper authorization to disclose PHI must include at least the following: (1) a meaningful description of the information to be disclosed; (2) the name of the person authorizing the disclosure; (3) the name of the person or class of persons to whom the disclosure can be made; (4) the purpose of the disclosure; (5) the expiration of authorization; and (6) the signature and date of the disclosing person or patient.[110]

Some legal scholars have argued that information shared within the MLP organization, whether between doctors, attorneys, social workers, etc., falls under either the treatment or healthcare‑operations exemptions to the HIPAA Privacy Rule.[111] However, given agency guidance encouraging schools partnering with community-based organizations to incorporate written consent for FERPA releases into registration procedures, SBMLPs should consider simply combining the written consent procedures for HIPAA and FERPA to avoid any accusations of unauthorized disclosure.[112]

2. FERPA Compliance Requirements for School Partners.

FERPA is a federal statute that prohibits any school receiving federal funds from releasing students’ “education records,” with some exceptions.[113] FERPA defines education records as “records, files, documents, and other materials” that are (1) “directly related to a student” and (2) “maintained by an educational agency or institution or by a person acting for such agency or institution.”[114]

Usually, FERPA requires schools to obtain written consent from a student’s parents or guardian before releasing information protected as an educational record.[115] The disclosure consent must be “signed and dated,” specify the records to be disclosed, indicate the “purpose of the disclosure,” and clearly identify to whom the disclosure will be made (here, the lawyers and healthcare professionals participating in the school-based MLP).[116] Department of Education guidance recommends that schools collaborating with community-based organizations (such as MLPs) incorporate written consent into the registration process, providing assurance that community-based organizations will have the necessary consent to access students’ educational records as “needed to provide its services to that student.”[117] Note that the “registration process” could be either for school registration or for registration to participate in the SBMLP services.[118]

While written consent is always advisable, the agency that enforces FERPA, the Family Policy Compliance Office (FPCO), released guidance indicating that sharing observations of behavior and personal knowledge does not violate FERPA, even if that information may otherwise exist in an education record.[119] This exception, though not yet challenged in the courts, would provide assurance to practitioners in an SBMLP that teachers can share concerns with attorney or healthcare partners based on their observations of a student’s behavior.[120] This is important because teachers are likely the first, and possibly the only, member of the partnership who will recognize that a child is experiencing housing insecurity, food insecurity, or behavioral health issues.[121] Additionally, students are more likely to express concerns triggering social determinants of health to a trusted individual with whom they regularly interact.[122]

3. Data Privacy: Conclusion.

Incorporating a process for informed consent at the outset of registration should ameliorate any concerns that the school or healthcare provider may run afoul of federal law. However, practitioners will want to remember that HIPAA and FERPA are merely a “floor” on which the states can add privacy protections.[123]

Therefore, while federal privacy laws—HIPAA and FERPA—do not pose an outright bar to collaboration, practitioners will want to consider these statutes and the applicable guidance in crafting a multidisciplinary partnership, and any SBMLP data‑sharing policy must consider the impact of supplemental state provisions.

B. Legal Ethics: How SBMLP Lawyers Can Protect Their Clients’ Information in Multidisciplinary Partnerships

Medical–legal partnerships (MLPs) have grappled for decades with how to navigate the collaboration between healthcare and legal professionals; now, school-based MLPs (SBMLPs) are adding educators to the mix.[124] Perhaps the most intuitive challenge that SBMLP practitioners face is the explicit prohibition against multidisciplinary legal practices in the American Bar Association (ABA) Model Rules of Professional Conduct.[125]

Generally, ABA Model Rule 5.4 prohibits lawyers from forming partnerships with nonlawyers if any of the activities of the partnership involve the practice of law.[126] At least two of the provisions in Rule 5.4 assume that the partnership requires payment for legal services.[127] However, the broadest subsection of the rule is not qualified by a fee provision: “A lawyer shall not form a partnership with a nonlawyer if any of the activities of the partnership consist of the practice of law.”[128]

The nonlawyer partnership prohibition has generated much debate; the debate over Rule 5.4, however, has largely failed to consider how these policies affect nonprofit legal services organizations. Consequently, there is little guidance regarding how this prohibition applies in a nonprofit setting.[129] Despite the ambiguity, disciplinary authorities have not enforced the rule against an attorney engaged in a multidisciplinary setting that is strictly nonprofit.[130] In 2007, the ABA passed a resolution supporting MLPs operated on a purely no-cost model and instituted a Medical-Legal Partnership Pro Bono Support Project.[131] Although those not familiar with MLPs may initially be concerned about a Rule 5.4 violation, the ABA’s institutional endorsement of MLPs (at least those that offer free services only) indicates that SBMLPs would garner the same institutional support. Additionally, many states are rejecting the nonlawyer partnership, at least on an experimental basis.[132]

Therefore, it is very unlikely that Rule 5.4 poses an outright bar to an SBMLP as a model. However, lawyers participating in the model will want to institute safeguards and procedures to protect some of the legal ethics issues most implicated by a multidisciplinary practice: professional independence, confidentiality, and attorney–client privilege.[133]

1. Professional Independence: How Attorneys Can Navigate the Delicate School-to-Attorney Relationship.

Model Rule of Professional Conduct 5.4(d)(3) prohibits a lawyer from practicing law where “a nonlawyer has the right to direct or control the professional judgment of a lawyer.”[134] Another provision in Rule 5.4 also prohibits a lawyer from allowing a person who “recommends . . . the lawyer to render legal services for another to direct or regulate the lawyer’s professional judgment in rendering such legal services.”[135]

Just as attorneys had to convince medical practitioners that their collaboration would not result in easier access to medical‑malpractice claims, attorneys seeking to partner with schools may find it necessary to decline certain types of cases in order to serve the overall collaborative goal of an SBMLP.[136] For instance, neither Erie nor HJA will represent students on education-related matters such as special-education or student disciplinary proceedings.[137] However, attorneys did mention that they would refer students to an attorney outside of the partnership collaborative.[138] Arguably, a policy of declining special education cases infringes on an attorney’s professional independence because it limits the scope of advocacy available to SBMLP clients. However, it is likely that such a restriction is within the boundaries of the model rules (so long as communicated with clients at the outset of representation) and may be a necessary trade-off for the benefits of collaborating.[139]

The ABA’s institutional endorsement of MLPs and the lack of enforcement against MLPs indicate that Rule 5.4 does not pose an outright bar to the SBMLP model. However, SBMLP lawyers should institute safeguards and procedures to protect their professional independence.[140] An independent judgment that merely incorporates the expertise of each member of the multidisciplinary team to make the most holistic and beneficial decision for the client may not be easily distinguishable from undue influence by a healthcare provider or school administrator that becomes an infringement on the attorney’s professional independence.

2. Client Confidentiality: Collaboration Does Not Inevitably Infringe on Confidentiality.

Lawyers have a strict duty to keep information learned during representation confidential.[141] This duty functions to establish and protect the trust that is necessary to assure open and candid communication between the client and lawyer.[142] Though clients can impliedly or explicitly authorize disclosure of confidential information, attorneys in an SBMLP will need to create policies at the outset that delineate the type of information all parties agree is impliedly authorized, as well as explain to the other partners that even authorized disclosures may be withheld if not in the best interest of the client.[143] Even aggregate data requests by school administrators—like a list of names and matters worked on within the clinic—should probably not be revealed by the lawyer.[144] Thus, to avoid undermining the attorney’s relationship with both clients and school employees, the parties should agree how the attorneys will respond to administrators’ requests for information prior to initiating the partnership.[145]

3. Attorney–Client Privilege: Weighing the Risk of Waiver Against the Rewards of Collaboration.

Attorney–client privilege is an evidentiary shield that protects certain confidential communication between the client and the lawyer.[146] If a client or a client’s attorney shares confidential information with a third party, the unprotected disclosure (or waiver) may destroy the shield.[147]

Protecting against attorney–client privilege waiver in an intentional and decidedly multidisciplinary setting poses a complex challenge. Simple authorization through an intake or registration form is likely sufficient to properly allow school officials or health professionals to disclose information to the attorney participating in the SBMLP.[148] But facilitating information flow the other direction (from the attorney to the health care provider or school employee) may cause an ill-advised waiver of attorney–client privilege.[149]

Strategic organization of the partnership may allow attorneys to extend the privilege even when disclosing client information to healthcare providers within the partnership.[150] However, because the courts are usually reluctant to extend the privilege to information disclosed to nonlawyer third parties, attorneys should not assume they will be able to protect information shared with SBMLP partners.[151] Instead, attorneys should weigh the costs and benefits of disclosure and, if in the client’s best interest, thoroughly explain the risks to the client in pursuit of obtaining the client’s informed consent for disclosure.[152]

The privilege shield only applies if a matter proceeds to trial.[153] There are a few hypothetical situations where attorney–client privilege could arise during the course of representation in an SBMLP: parents wanting an attorney to testify in a child custody case, child protective services seeking the attorney’s testimony to support removal hearings, or a criminal act by one of the children in the school who has previously consulted with the attorney. However, given the existing data on the types of representation and matters SBMLP attorneys pursue, it is unlikely that litigation is a significant risk.[154] Existing SBMLP have focused on the family, housing, benefits, and education needs of their clients, prioritizing a nonadversarial path to patients’ complex needs.[155] Still, attorneys participating in SBMLPs will need to weigh the risks and benefits of disclosure to the nonlawyer partners.[156]

4. Legal Ethics: Conclusion.

As with many ethical questions, those SBMLPs present do not have clear answers. Many will require a case-by-case analysis while balancing the risks and benefits to the patient–client. Although the rules explored do not pose an outright bar to SBMLPs, which are already operating in at least three states, attorneys should continue to consult the ABA and state law guidance concerning the propriety of the partnership.[157]

IV. Conclusion

For almost three decades, MLPs have proven capable of navigating the novel legal ethics and data privacy concerns implicated by the integration of health and legal services.[158] As MLPs seek to partner with schools to combat the medical and health-harming legal needs that school-age youth and their families encounter, they will confront similar—though unique—challenges posed by data privacy laws and legal ethics rules.[159] To sort out these issues in a new context, SBMLPs will likely require the same type of institutional support and incentives by insurers, policymakers, and the ABA that MLPs received.[160] Convincing schools that the benefits MLPs can bring outweigh any risks is critical to forming the partnerships necessary to facilitate SBMLPs.[161] As with MLPs, many of the challenges raised in implementation will likely require unique solutions. As such, it seems less important that all practitioners know all the answers, and more important that they ask the right questions. Scholars concerned with youth incarceration, health disparities, or educational innovation can support SBMLPs by offering more scholarship to guide SBMLPs as they grow and expand. SBMLP enables attorneys, healthcare providers, and educators to address the overlapping needs of at-risk youth and their families by moving much-needed legal and health services into schools.[162]

Tiffany Penner

This story is adapted from a success story by the Georgetown Health Justice Alliance, a school-based medical–legal partnership. See Nat’l Ctr. for Med.-Legal P’ship & Sch.-Based Health All., School-Based Health & Medical-Legal Partnerships 2 (2018) [hereinafter Fact Sheet], https://medical-legalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/School-Based-Health-and-Medical-Legal-Partnership-1.pdf [https://perma.cc/D9WC-H3FY].

See infra note 83 and accompanying text.

See infra notes 28–31, 37–39 and accompanying text.

See Ruth Bell et al., Global Health Governance: Commission on Social Determinants of Health and the Imperative for Change, 38 J.L. Med. Ethics 470, 471, 478 (2010); see also Jessica Mantel, Tackling the Social Determinants of Health, 33 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. 217, 238 (2017) (urging healthcare providers to move beyond medically treating patients’ symptoms to combating root causes of poor health by addressing the social determinants of health).

Shaila Dewan, Here’s One Issue That Could Actually Break Partisan Gridlock, N.Y. Times (Nov. 24, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/24/us/criminal-justice-reform-republicans-democrats.html [https://perma.cc/8WT3-U2QD] (“[C]riminal justice reform offers something for just about everyone: social justice crusaders who point to yawning racial disparities, fiscal conservatives who decry the extravagant cost of incarceration, libertarians who think the government has criminalized too many aspects of life and Christian groups who see virtue in mercy and redemption.”).

Nat’l Acads. Scis., Eng’g, & Med., Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity 33 (James N. Weinstein et al. eds., 2017), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425848/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK425848.pdf [https://perma.cc/HKK4-PWQJ] (discussing health disparities by racial and ethnic categories). See generally 2018 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, Agency for Healthcare Rsch. & Quality, https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr18/index.html [https://perma.cc/6ULD-37PG] (last reviewed Apr. 2020) (documenting healthcare quality and disparities by racial and socioeconomic groups for the sixteenth year).

Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 2 (presenting facts on the only two SBMLPs recognized by the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnerships in 2018).

This Comment explores these challenges because the attorneys leading the implementation of the three MLPs identified in this Comment repeatedly raised these challenges as barriers they faced in expanding and sustaining the SBMLPs. See Interview with Yael Cannon, Dir., Health Just. All. L. Clinic, in Wash., D.C. (Sept. 11, 2020) [hereinafter Cannon Interview]; Interview with Martha Glynn, Site Med. Dir., Erie Sch. Based Health, Erie Fam. Health Cntrs., in Chi., Ill. (Sept. 23, 2020) [hereinafter Glynn Interview]; Interview with Kassi Gonzalez, Staff Att’y, Tex. Legal Servs. Ctr., & MLP Att’y, People’s Cmty. Clinic, in Austin, Tex. (July 11, 2020).

Generally, the National School-Based Health Alliance represents a broad coalition to provide comprehensive medical services to at-risk youth in public schools through SBHCs. What We Do, Sch.-Based Health All., https://www.sbh4all.org/what-we-do/ [https://perma.cc/89HD-NUHA] (last visited Dec. 18, 2020). The National Center for Medical-Legal Partnerships provides thought leadership and training for healthcare professionals and attorneys seeking to establish MLPs, usually in a hospital or clinical setting. About the National Center, Nat’l Ctr. for Med.-Legal P’ship, https://medical-legalpartnership.org/about-us/ [https://perma.cc/JH97-QYSX] (last visited Dec. 18, 2020).

See Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 4.

Although created by the Author, these graphics were inspired by similar graphics used in an MLP training publication by the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership at George Washington University. See Jane Hyatt Thorpe et al., Med.-Legal P’ship Fundamentals, Information Sharing in Medical-Legal Partnerships: Foundational Concepts and Resources 1, 6 fig.1 (2017), https://medical-legalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Information-Sharing-in-MLPs.pdf [https://perma.cc/XNU6-8PPA] (using similar graphics to describe the various degrees of collaboration in MLP structural models).

See infra notes 13, 15 and accompanying text.

The Legal Services Corporation (LSC), a congressionally established nonprofit corporation, conducted a “Justice Gap” report in 2017 to measure the justice gap (defined as “the difference between the civil legal needs of low-income Americans and the resources available to meet those needs”) among low-income Americans. Legal Servs. Corp., The Justice Gap: Measuring the Unmet Civil Legal Needs of Low-Income Americans 6, 9 (2017), https://www.lsc.gov/sites/default/files/images/TheJusticeGap-FullReport.pdf [https://perma.cc/EBN6-8HJR]; About LSC, Legal Servs. Corp., https://www.lsc.gov/about-lsc [https://perma.cc/KU68-FF53] (last visited Oct. 25, 2020). The “Justice Gap” report found that 80% of the eighteen million low-income families with children under eighteen (as compared to only 71% of low-income households generally) experienced at least one civil legal problem in 2016, with 35% experiencing more than six civil legal problems. About LSC, supra, at 6, 51. The majority of civil legal problems experienced by parents or guardians of minor children related to health (46%). Others included finances (45%), benefits and income support (28%), children and custody (27%), family (26%), and education (25%). Of those low-income parents or guardians of minor children, 87% reported receiving inadequate or no professional legal help with their civil legal problems. Two of the top three reasons given for not seeking legal help were (1) no knowledge of resources available and (2) failure to identify the problem as legal until too late. Id. at 51.

Kristin Anderson Moore et al., Child Trends, Making the Grade: A Progress Report and Next Steps for Integrated Student Supports 12 (2017), https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ISS_ChildTrends_February2018.pdf [https://perma.cc/82NZ-5XNQ] (explaining the response by many policymakers and school administrators to implement “school-based approach[es] to promoting students’ academic achievement and educational attainment by coordinating a seamless system of wraparound supports for the child, the family, and schools, to target students’ academic and nonacademic barriers to learning”); see also 20 U.S.C. § 7272 (encouraging implementation of “pipeline services” or “integrated student supports” through “[f]amily and community engagement and supports, which may include engaging or supporting families at school or at home,” “[s]ocial, health, nutrition, and mental health services” and “[j]uvenile crime prevention and rehabilitation programs”).

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), passed in 2015, became the first federal education bill to encourage the importance of integrated support services—or programs that seek to combat barriers caused by nonacademic social factors like homelessness, food insecurity, legal issues, or access to healthcare. See Moore et al., supra note 14, at 1–3.

See Barbara Fedders & Jason Langberg, School-Based Legal Services as a Tool in Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline and Achieving Educational Equity, 13 U. Md. L.J. Race Religion Gender & Class 212, 218, 229 (2013).

Id. at 229.

See Leigh Goodmark, Can Poverty Lawyers Play Well with Others? Including Legal Services in Integrated, School-Based Service Delivery Programs, 4 Geo. J. on Fighting Poverty 243, 253 (1997).

Id.

Id. at 253–54.

Id. at 254.

Although this Comment only explores the first of these challenges (intraorganizational conflicts), SBMLP practitioners will need to consider the others. Id. at 254–56 (explaining how an early SBLS collaborative failed as a result of the lawyers “jeopardizing” the relationships with city officials that allowed them to leverage services for clients “by suing the officials responsible for these same programs”).

About School-Based Health Care, Sch.-Based Health All., http://www.sbh4all.org/school-health-care/aboutsbhcs/ [https://perma.cc/JJC4-3U4P] (last visited Oct. 26, 2020). The most recent survey on SBHC models reports that 81.7% of SBHCs are located at a physical, fixed site on a school campus, 11.5% are telehealth resources accessed on campus but delivering care remotely, 3.8% are “[s]chool-linked” requiring students to travel to a nearby location off-campus to access and receive care, and 3% are mobile, operating out of a van parked on or near school campus. H. Love et al., Sch.-Based Health All., 2016–17 School-Based Health Care Centers Census Report (2018), https://www.sbh4all.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2016-17-Census-Report-Final.pdf [https://perma.cc/8D8W-D8KT].

About School-Based Health Care, supra note 23.

Love et al., supra note 23.

Id.

Id.

See Jessica Mantel & Renee Knake, Legal and Ethical Impediments to Data Sharing and Integration Among Medical Legal Partnership Participants, 27 Annals Health L. 183, 187 (2018) (explaining that healthcare providers are often first to identify social determinants of health because “[p]atients’ trust in medical professionals . . . promotes individuals sharing sensitive information with their providers, such as personal information on issues such as domestic violence, financial hardship, immigration concerns, and other legal and social challenges”); Alison R. Zisser & Maureen Stone, Health, Education, Advocacy, and Law: An Innovative Approach to Improving Outcomes for Low-Income Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 12 J. Pol’y & Prac. Intell. Disabilities 132, 133 (2015) (“Attorneys possess a unique expertise among healthcare teams in addressing the social determinates of health and may work to ensure that law and policy addressing health and safety are enforced.”).

See FAQs: About Medical-Legal Partnership, Nat’l Ctr. for Med.-Legal P’ship, https://medical-legalpartnership.org/faq/ [https://perma.cc/A56L-3QGK] (last visited Oct. 29, 2020); Thorpe et al., supra note 11, at 21.

See Leah Porter & Amara Azubuike, Medical-Legal Partnerships, Am. Bar Ass’n, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/young_lawyers/publications/tyl/topics/niche-practice-areas/medical-legal-partnerships-innovative-legal-aid/ [https://perma.cc/G2T8-FBM2] (last visited Aug. 25, 2021); Elizabeth Tobin-Tyler & Benjamin Ahmad, Milbank Mem’l Fund, Marrying Value-Based Payment and the Social Determinants of Health Through Medicaid ACOs: Implications for Policy and Practice 5 (2020), https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Medicaid-AC0s-and-SD0H.ver5_.pdf [https://perma.cc/A765-3EQG] (explaining that many states have responded to the shifted policy with strategies that fall within three main buckets: (1) requiring healthcare providers to screen for social risks to health; (2) incentivizing, or even requiring, healthcare providers to partner with social services providers; (3) incentivizing, or even requiring, for some quality measurement by SDOH metrics).

See Mantel, supra note 4, at 238 (“In response to various policies adopted under the [Affordable Care Act], providers are increasingly allocating their time and resources to the social factors adversely impacting their patients’ health.”). In 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services implemented four new regulations formalizing options for states to incentivize Medicaid providers to incorporate nonmedical factors that impact long-term health such as abuse, environmental hazards, food or housing insecurity, and employment needs. See David Machledt, Commonwealth Fund, Addressing the Social Determinants of Health Through Medicaid Managed Care 4, 6 (2017), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2017_nov_machledt_social_determinants_medicaid_managed_care_ib_v2.pdf [https://perma.cc/BPK8-S8CS] (discussing how 42 C.F.R. §§ 438.3(e), 438.6(b)–(c), and 438.208(b) “strengthen options for states to pursue activities centered on social determinates of health”). Additionally, the Affordable Care Act requires tax-exempt hospitals to engage community members and community-based organizations in performing a “community health needs assessment” every three years to ensure that the hospital is appropriately focused on the health problems specific to its geographical area. See Requirements for 501(c)(3) Hospitals Under the Affordable Care Act—Section 501(r), IRS, https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-organizations/requirements-for-501c3-hospitals-under-the-affordable-care-act-section-501r [https://perma.cc/EP58-HERG] (last visited Nov. 2, 2020); Elizabeth Tobin-Tyler & Joel B. Teitelbaum, Medical Legal Partnership: A Powerful Tool for Public Health and Health Justice, 134 Pub. Health Reps. 201, 203 (2019) (discussing the requirements of 26 U.S.C. § 501(r)(3) (2011)).

See supra note 30 and accompanying text.

See Ross D. Silverman, Poverty, Health, and Law: Readings and Cases for Medical-Legal Partnership, 34 J. Legal Med. 327, 334 (2013); What’s on the MCAT Exam?, AAMC, https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-medical-school/article/whats-mcat-exam/ [https://perma.cc/XSH5-58PT] (last visited Oct. 28, 2020) (listing “[c]ultural and social differences influence [on] wellbeing” and “[s]ocial stratification and access to resources influence well-being” as “[f]oundational [c]oncepts”).

Amy Lewis Gilbert & Stephen M. Downs, Medical Legal Partnership and Health Informatics Impacting Child Health: Interprofessional Innovations, 29 J. Interprofessional Care 564, 564, 565 (2015).

See Barry Zuckerman et al., Why Pediatricians Need Lawyers to Keep Children Healthy, 114 Pediatrics 224, 225–27 (2004).

See Gilbert & Downs, supra note 34, at 564, 565, 568 (“Health economists have estimated that medical care accounts for only 10% of overall health, with social, environmental, and behavioral factors accounting for the remaining 90%.”); see also Maia Crawford et al., Milbank Mem’l Fund, Population Health In Medicaid Delivery System Reforms 2 (2015), http://www.milbank.org/uploads/documents/papers/CHCS_PopulationHealth_IssueBrief.pdf [https://perma.cc/75AG-BJJQ] (finding that access to medical care prevents only 10% of premature deaths, with “nonmedical indicators” such as behavior, environment, and social status comprising the cause of 90% of preventable deaths).

See Mantel, supra note 4, at 224, 225 (quoting Laura McGovern et al., Health Affs., Health Policy Brief: The Relative Contribution of Multiple Determinants to Health Outcomes 2 (2014), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20140821.404487/full/healthpolicybrief_123.pdf [https://perma.cc/C5Q4-LHQG]).

See Zisser & Stone, supra note 28, at 133.

See Tobin-Tyler & Teitelbaum, supra note 31, at 201 (citing data accessed from the Milken Institute School of Public Health in October 2018).

Home, Nat’l Ctr. for Med.-Legal P’ship, https://medical-legalpartnership.org [https://perma.cc/V879-SR4M] (last visited Oct. 25, 2020) (reporting the latest data on recognized medical–legal partnerships).

See Thorpe et al., supra note 11, at 6.

Id. at 6 fig.1.

Id.

Id. at 7 fig.2 (describing the varied levels of integration in the three models and explaining that the healthcare institution in a referral network would view “legal professionals [as] valued allies[] but separate from [healthcare] services”).

Id. at 6 fig.1.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id. at 6 fig.1, 7 fig.2; see Jeffrey David Colvin et al., Integrating Social Workers into Medical-Legal Partnerships: Comprehensive Problem Solving for Patients, 57 Soc. Work 333, 335–36, 338 (2012) (arguing that patients are less likely to obtain services when getting access depends on their access to transit and other potential barriers); Jessica Mantel & Leah Fowler, Thinking Outside the Silos: Information Sharing in Medical-Legal Partnerships, 40 J. Legal Med. 369, 383, 386 (2020) (arguing that an MLP attorney is more likely to succeed in representation if building on a patient’s relations with a social worker partnership member because of that persons “ongoing relationship with the patient”).

Thorpe et al., supra note 11, at 6 fig.1.

See id.

Id.; see also infra Part III (discussing patient consent needed to authorize transfer of patient health information under HIPAA and FERPA, as well as the legal ethics rules that may require that the attorney obtain consent before sharing information with nonlawyer partners).

Thorpe et al., supra note 11, at 6 fig.1.

Id. at 6 fig.1, 7 fig.2 (describing the varied levels of integration in the three models).

See i d. at 6 fig.1 (anticipating potential concerns about data privacy and legal ethics, the authors note that “a firewall may be maintained between” protected health information “and legal information” in any shared data management system).

Id. at 7 fig.2; see also Mantel, supra note 4, at 246–47 (“Medical-legal partnerships assist patients with legal problems that affect stress levels or otherwise contribute to poor health.”).

See, e.g., Mantel & Knake, supra note 28, at 193–94, 196–97, 200–01 (describing the legal and ethical hurdles that healthcare and legal professionals face when sharing information through MLPs); Mantel & Fowler, supra note 49, at 373–74 (describing how barriers to information-sharing between healthcare providers and MLP attorneys “could hinder the attorney’s ability to provide effective legal representation”). In the MLP context, the data privacy law discussion has centered on HIPAA compliance when health and legal professionals seek to share data as part of a coordinating staff or one organization partnership model. See generally Mantel & Knake, supra note 28 (detailing the collaborative process between legal and medical professionals in more integrated MLP models and ensuing HIPAA compliance requirements). The discussion concerning legal ethics issues has primarily focused on attorney–client privilege, confidentiality, and conflicts of interest. Id. at 197, 200–01. A thorough discussion regarding these issues in an MLP context is outside the scope of this Comment.

See Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 1–2, 4.

See infra Part II (documenting the only two SBMLPs recognized by the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnerships).

See Daniel R. Taylor et al., Keeping the Heat on for Children’s Health: A Successful Medical-Legal Partnership Initiative to Prevent Utility Shutoffs in Vulnerable Children, 26 J. Health Care Poor &Underserved 676, 676–78 (2015); Gilbert & Downs, supra note 34, at 564–65.

See Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 4.

See Jacob Kang-Brown et al., Vera Inst. Just., A Generation Later: What We’ve Learned About Zero Tolerance in Schools 5–6 (2013), https://www.vera.org/downloads/Publications/a-generation-later-what-weve-learned-about-zero-tolerance-in-schools/legacy_downloads/zero-tolerance-in-schools-policy-brief.pdf [https://perma.cc/9M7K-J8BW].

A recognition of the independent, causal relationship between youth interaction with the criminal justice system and degraded mental and physical health in adulthood has led to a movement within pediatric care to engage with reform in the criminal justice system and care delivery models that address social determinants of health. Elizabeth S. Barnert et al., How Does Incarcerating Young People Affect Their Adult Health Outcomes?, Pediatrics, Feb. 2017, at 1, 7 (concluding the presentation of a study on the relationship between youth incarceration and poor adult health, the researchers urged pediatricians to “increase efforts to (1) prevent youth incarceration by addressing key behavioral and social determinants of health and (2) mitigate potential downstream health effects of youth incarceration”); Am. Acad. Pediatrics Comm’n on Adolescence, Health Care for Youth in the Juvenile Justice System, 128 Pediatrics 1219, 1232–33 (2011), https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/128/6/1219.full.pdf [https://perma.cc/5YMP-UEE2] (encouraging pediatricians to take action to prevent youth incarceration). In addition to the medical community’s increased focus on the impact of youth involvement with the criminal justice system, the legal community has been very active in drawing attention to the way that students’ experiences with school discipline overwhelmingly indicate a future of incarceration. See Kang-Brown et al., supra note 62, at 5–6, (noting that while the “school-to-prison pipeline” may or may not be real, one thing is clear: “Additional years of compulsory education do help to prevent people from engaging in delinquency and crime”). See generally Deborah Fowler et al., Tex. Appleseed, Texas’ School-to-Prison Pipeline (2010), http://www.njjn.org/uploads/digital-library/Texas-School-Prison‑Pipeline‑School‑Expulsion_Texas-Appleseed_Apr2010.pdf [https://perma.cc/9BCX-8HQW] (presenting extensive empirical data on the correlation between school discipline and future incarceration); Farnel Maxime, Zero-Tolerance Policies and the School to Prison Pipeline, Shared Just. (Jan. 18, 2018), http://www.sharedjustice.org/domestic-justice/2017/12/21/zero-tolerance-policies-and-the-school-to-prison-pipeline [https://perma.cc/9A24-2HGB] (describing the link between zero-tolerance school policies and incarceration).

See Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 2.

Kate Marple, Nat’l Ctr. for Med.-Legal P’ship, Using the Law to Inform Empowered Patient Care in Austin 2, 13 (2018), https://medical-legalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Using-the-Law-to-Inform-Empowered-Patient-Care-in-Austin.pdf [https://perma.cc/ZN9H-6GRG]; see E-mail from Kassi Gonzalez, Staff Att’y, Tex. Legal Servs. Ctr., and MLP Att’y, People’s Cmty. Clinic in Austin, Tex., to Author (Oct. 8, 2020, 15:23 CDT) [hereinafter Gonzalez E-mail] (on file with author).

See Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 5.

See id.; Cannon Interview, supra note 8; Glynn Interview, supra note 8.

See, e.g., Lisa Kessler et al., Co-Creating a Legal Check-Up in a School-Based Health Center Serving Low-Income Adolescents, 15 Progress in Cmty. Health P’ships 203, 204, 206–10, 214 (2021) (discussing the SBMLP’s two-step screening tool that identified “clients with clinically significant issues around education, nutrition, and behavioral health”); see also Univ. S.F. Cal., Social Needs Screening Tool Comparison Table, SIREN (2019), https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/SocialNeedsScreeningToolComparisonTable [https://perma.cc/H4Y6-5QQ4] (providing a compilation of the screening content of the “most widely used social health screening tools to facilitate comparisons” for organizations that lack the resources to develop tailored tools).

Cannon Interview, supra note 8; Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 5.

Cannon Interview, supra note 8; Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 5.

Glynn Interview, supra note 8.

Id.; see Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 2–3. One of Erie’s most notable client success stories illustrates the way that the health and legal needs of low-income clients often intersect. Id. at 2. In summary, an SBMLP healthcare provider identified that every child in a family suffered from lead poisoning but was not allowed to change federal housing units because the children’s lead levels did not meet the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) trigger to warrant a relocation. After referral from the healthcare provider, the attorneys sued the housing authority to allow the family to move federal housing units without losing their subsidy. Additionally, through working on the case, the attorneys realized that HUD had failed to update lead safety standards in accordance with recent Center for Disease Control guidelines. State-wide advocacy initiated by the Erie SBMLP led to state-wide legislation to update local preventative lead policies. Id.

Kessler et al., supra note 68, at 204.

See Marple, supra note 65, at 13–15; supra Section I.B (presenting the varied levels of integration within the three structural models of MLPs identified by the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnerships).

See Gonzalez E-mail, supra note 65.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id. (describing the information shared as “case numbers, logged outreaches, and case outcomes with the clinic”).

See supra Section I.B (discussing the various levels of integration in MLP models); Mantel & Knake, supra note 28, at 190; Colvin et al., supra note 49, at 335 (arguing that patients are more likely to receive access to care when medical, legal, and social resources are co-located).

See Stacy L. Brustin, Legal Services Provision Through Multidisciplinary Practice—Encouraging Holistic Advocacy While Protecting Ethical Interests, 73 U. Colo. L. Rev. 787, 792 (2002) (explaining that because the poor are often isolated and lack travel resources, a multidisciplinary practice in one location “allows for greater efficiency and continuity of care”).

See Mantel & Knake, supra note 28, at 190–91 (explaining that “rather than simply helping a patient-client dealing with domestic violence obtain a restraining order, as occurs under the referral MLP model, an integrated, multidisciplinary MLP can also provide behavioral health counseling, assist with developing a safety plan, locate alternative housing, and secure financial support”); see also Goodmark, supra note 18, at 244–45 (elaborating on the difficulties those in poverty have in obtaining access to the legal system and clarifying how integrated service programs can provide solutions).

See infra Section III.A.2 (discussing how schools participating in SBMLP can navigate FERPA compliance).

Robert Belfort et al., Robert Wood Johnson Found., Integrating Physical and Behavioral Health: Strategies for Overcoming Legal Barriers to Health Information Exchange 5 (2014).

See supra notes 38–40 and accompanying text.

See Fact Sheet, supra note 1, at 5 (discussing how one SBMLP routinely refers education-related legal matters to outside legal services agencies out of respect for the SBMLP’s relationship with the school).

While SBMLPs are too sparse to make this more than a suggestion, how hospitals and attorneys have navigated potentially adversarial disputes in the MLP context may be a useful—and promising—comparison. See Mantel & Knake, supra note 28, at 188–91.

See John A. Knopf et al., School-Based Health Centers to Advance Health Equity: A Community Guide Systematic Review, 51 Am. J. Preventive Med. 114, 118 (2016) (finding “[s]ubstantial educational benefits” for schools providing students with school‑based healthcare services, including “reductions in rates of school suspension or high school non-completion, and increases in grade point averages and grade promotion”); Joshua Morris & Jennifer Zellner, Medical Legal Partnerships and School-Based Health Centers 19 (unpublished manuscript) (on file with Houston Law Review) (noting that the causes and effects of chronic absenteeism is “remarkably similar” whether attributed to health or discipline issues); see also Moore et al., supra note 14, at 13–14 (discussing how integrated support services—or services that address health and justice needs of students and families—have had a positive impact on students’ academic performance). But see Matt Barnum, Do Community Schools and Wraparound Services Boost Academics? Here’s What We Know, Chalkbeat (Feb. 20, 2018, 12:14 PM), https://www.chalkbeat.org/2018/2/20/21108833/do-community-schools-and-wraparound-services-boost-academics-here-s-what-we-know [https://perma.cc/GU8A-6DY7] (noting that some of the data in the Child Trends report on integrated support services is inconclusive and more research is needed to show whether addressing students’ nonacademic needs correlates to an improvement in their academic performance).

See supra Section I.A.1–2 (presenting background on SBLS and SBHCs); see also Mantel, supra note 4, at 224–28, 255 (discussing an Ohio-based MLP that recently decided to partner with local schools to address health disparities in “infant mortality, obesity, asthma, unintentional injuries, and early childhood development”).

See Kessler et al., supra note 68, at 204.

See James Anderson et al., The Effects of Holistic Defense on Criminal Justice Outcomes, 132 Harv. L. Rev. 819, 825, 862–67 (2019) (measuring the success of the holistic defense movement); Robin Steinberg, Heeding Gideon’s Call in the Twenty-First Century: Holistic Defense and the New Public Defense Paradigm, 70 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 961, 963 (2013) (describing the holistic defense movement).

A Baltimore-based MLP (not partnered with a school), Project HEAL (Health, Education, Advocacy, and Law), is specifically focused on serving “children with intellectual disability, developmental disabilities, and mental health concerns in matters specifically related to the child’s disability,” like special-education matters. See Zisser & Stone, supra note 28, at 133. The data provided by a healthcare provider is critical in supporting these applications. Id. at 134.

See Moore et al., supra note 14, at 4–7, 12 (noting educators’ insight and ability to perceive nonacademic factors that influence students’ overall well-being, such as homelessness or hunger); see also infra note 122 and accompanying text.

See supra note 31 and accompanying text; Neal A. DeJong et al., Identifying Social Determinants of Health and Legal Needs for Children with Special Health Care Needs, 55 Clinical Pediatrics 272, 272–73 (2016); see also Mantel, supra note 4, at 275 (presenting the benefits that medical providers stand to gain by engaging in partnerships—like MLPs—to address social determinants of health).

Ed Mitzen, The Secrets to Building Better Business Partnerships, Forbes (July 17, 2020, 1:15 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbooksauthors/2020/07/17/the-secrets-to-building-better-business-partnerships/ [https://perma.cc/9AMZ-RQ9F] (“[I]t’s in everyone’s vested interest to . . . regularly communicate.”); Rhett Power, 4 Ways to Build a Successful Partnership, Inc. (July 31, 2018), https://www.inc.com/rhett-power/4-ways-to-build-a-successful-partnership.html [https://perma.cc/9S5J-RYHS] (“Long-term success also requires honesty and transparency from both partners. That means maintaining open and frequent communication as well as personal interaction as often as possible.”).

See infra Section III.A (discussing HIPAA and FERPA compliance requirements).

See Marcia M. Boumil et al., Multidisciplinary Representation of Patients: The Potential for Ethical Issues and Professional Duty Conflicts in the Medical-Legal Partnership Model, 13 J. Health Care L. & Pol’y 107, 124–26 (2010) (illustrating a common scenario where the ethical codes of a doctor, social worker, and lawyer working in an MLP will conflict); see also Janet Dolgin et al., Lessons Learned from a New Medical-Legal Partnership: Patient Screening, Information and Communication, 31 Health L. 34, 39 (2019) (suggesting the need for a “new, supplemental professional code of ethics, appropriate for interdisciplinary work among medical clinicians and lawyers”); Alexis Anderson et al., Professional Ethics in Interdisciplinary Collaboratives: Zeal, Paternalism and Mandated Reporting, 13 Clinical L. Rev. 659, 694–97 (2007) (discussing duties of a lawyer working with a social worker who is obligated to report abuse).

See Thorpe et al., supra note 11, at 4 (explaining that MLPs, prefaced on the need for healthcare providers and attorneys to communicate about the overlapping health and legal needs of a client, may implicate federal and state privacy laws, such as HIPAA).

See Gregory Riggs, Taking HIPAA to School: Why the Privacy Rule Has Eviscerated FERPA’s Privacy Protections, 47 J. Marshall L. Rev. 1047, 1066–68 (2014) (discussing the challenges posed by HIPAA and FERPA’s “overlapping regulatory schemes”). The Code of Federal Regulations’ definition for “protected health information” specifically “excludes individually identifiable health information” included “[i]n education records covered by” FERPA. See 45 C.F.R. § 160.103 (defining “[p]rotected health information”).

Abigail English, Nat’l Assembly on Sch. Based Health Care, The HIPAA Privacy Rule and FERPA: How Do They Work in SBHCs? (2021), http://ww2.nasbhc.org/RoadMap/PracticeCompliance/HIPAA and FERPA and SBHC NASBHC.pdf [https://perma.cc/R562-T5MX].

See Ass’n of State & Territorial Health Offs., Comparison of FERPA and HIPAA Privacy Rule for Accessing Student Health Data 2 (2012), https://www.astho.org/uploadedFiles/Programs/Preparedness/Public_Health_Emergency_Law/Public_Health_and_Schools_Toolkit/04-PHS Comparing F and H FS Final 3-12.pdf [https://perma.cc/NKE9-CYKJ] (“A student’s health records, including immunization information and other records maintained by a school nurse, are considered part of the student’s education record and are protected from disclosure under FERPA.”). But see id. (“If a school’s education records are not covered under FERPA . . . they may be subject to HIPAA as a covered entity if they transmit health information electronically.”).

See 45 C.F.R. § 160.103 (defining “[p]rotected health information”).

See id. § 164.506.

See Boumil et al., supra note 100, at 132 (“[P]rotected health information [is] regulated under the HIPAA Privacy Rule, regardless if it is delivered on paper, via telephone, spoken in person, faxed, or emailed.”).

See supra Section I.B (discussing the various models).

A 2009 survey of forty-five active MLPs found that “79.5% of [MLP] sites share patient referral information verbally via telephone or in person, 54.4% of sites allow advocates access to patients’ medical records, 52% share referral information via email, 50% share referral information via fax, and 43.2% deliver referral information in person.” Boumil et al., supra note 100, at 108 n.7, 132 n.157 (explaining that regardless of the method used, HIPAA is implicated if the content of the communication relates to protected health information); see also Mantel & Fowler, supra note 49, at 373 & n.16 (explaining that the rules of professional conduct governing medical professionals allow providers to disclose patient information only if the patient consents).

45 C.F.R. § 164.508(c)(1); see also Boumil et al., supra note 100, at 135 n.178 (expanding on the requirements for disclosure, “such as notice that the authorization may be revoked; the ability or inability to condition treatment, payment, enrollment, or eligibility upon the authorization; and the potential for information disclosed pursuant to the authorization to be subject to redisclosure by the recipient and therefore no longer protected”).

See Thorpe et al., supra note 11, at 11.

Fam. Pol’y Compliance Off., U.S. Dep’t Educ., The Family Education Rights and Privacy Act Guidance on Sharing Information with Community-Based Organizations 7 (2020) [hereinafter Q. 11], https://studentprivacy.ed.gov/sites/default/files/resource_document/file/ferpa-and-community-based-orgs.pdf [https://perma.cc/WS33-7G2N] (“For activities that do not fit within the statutory exceptions to consent, we recommend that schools . . . and/or community-based organizations build written consent into the registration process.”).

20 U.S.C. § 1232g(b); see also Lynn M. Daggett & Dixie Snow Huefner, Recognizing Schools’ Legitimate Educational Interests: Rethinking FERPA’s Approach to the Confidentiality of Student Discipline and Classroom Records, 51 Am. U. L. Rev. 1, 7–9 (2001) (discussing situations where disclosure is allowed without prior student consent). Note that FERPA regulates student privacy in several other ways, which are outside the scope of this Comment. See Lynn M. Daggett, FERPA in the Twenty-First Century: Failure to Effectively Regulate Privacy for All Students, 58 Cath. U. L. Rev. 59, 62 (2008) (summarizing FERPA’s four essential requirements, of which only one, “schools cannot disclose education records or their contents to third parties without the written consent of the parent/adult student,” is within this scope of this Comment).

20 U.S.C. § 1232g(a)(4).

20 U.S.C. § 1232g(b)(2). But see Daggett & Huefner, supra note 113, at 7–9 (noting the many exceptions to the general prohibition on disclosure without consent).

What Must a Consent to Disclose Education Records Contain?, U.S. Dep’t. Educ., https://studentprivacy.ed.gov/faq/what-must-consent-disclose-education-records-contain [https://perma.cc/8EYU-VPA3] (last visited Oct. 30, 2020); see also 34 C.F.R. § 99.30.

See supra note 112 and accompanying text.

See Q. 11, supra note 112, at 7–8 (noting that FERPA does not address which party is responsible for obtaining consent and that “[t]here is nothing in FERPA that would preclude a community-based organization from obtaining” consent in accordance with the requirements in 34 CFR § 99.30(b)).

See Lynn M. Daggett, Book 'Em?: Navigating Student Privacy, Disability, and Civil Rights and School Safety in the Context of School-Police Cooperation, 45 Urb. L. 203, 213 n.63 (2013) (“FERPA does not protect the confidentiality of information in general. FERPA does not apply to the disclosure of information derived from a source other than education records, even if education records exist which contain that information. As a general rule, information that is obtained through personal knowledge, personal observation, or hearsay, and not specifically obtained from an education record, is not protected from disclosure under FERPA. . . . These statements appear to be observational or the speaker’s opinion.” (quoting Letter to Anonymous, 107 LRP 48036 (FPCO 2007))).

Id. (cautioning that because this exception for “observed behavior” has neither been tested in the courts nor explicitly noted in the statute there is no assurance that courts will defer to the agency’s interpretation as reasonable).

See supra note 95 and accompanying text.

See Mantel & Knake, supra note 28, at 187 (discussing that it is the patient’s trust in a physician that makes them more likely to be confided in by a patient than, for instance, an attorney).

A survey of state laws that supplement the federal privacy laws discussed supra are outside of the scope of this Comment. At a cursory level, practitioners should know that state laws tend to be more protective of patient/student information. See Thorpe et al., supra note 11, at 15, 22 (explaining that state laws are often more stringent and protective of patients’ rights); see also Tex. Educ. Code Ann. § 38.009 (“A school administrator, nurse, or teacher is entitled to access to a student’s medical records maintained by the school district for reasons determined by district policy. A school administrator, nurse, or teacher who views medical records under this section shall maintain the confidentiality of those medical records.”).