I. Introduction

On October 30th, 2019, millions of Americans gathered around their televisions and mobile screens to watch Game 7 of the World Series between the Houston Astros and Washington Nationals.[1] The World Series is widely regarded as the pinnacle of baseball competitions, announcing to the nation the best team of the year.[2] Imagine then, if those millions of fans waited with bated breath for this championship game to end . . . and it ended with a tie.

In the American court system, Supreme Court decisions are the World Series of adjudication. The nine Justices on this high Court represent “the apex of the judicial system” and serve as the ultimate decision-makers on challenging and complicated legal questions.[3] While it’s true that the courtroom decisions of the Supreme Court do not have quite the same live audience as a World Series game, the effects of the decisions made by the Justices have an even greater impact.[4] The Supreme Court is the final forum for those seeking justice, the protector of civil liberties, the preserver of the Constitution, and the disciplinarian of entities who attempt to reach beyond their powers.[5] Thus, when the esteemed Justices on this highest Court take on a contested issue, similarly, a tie can feel confusing, frustrating, and pointless.

Surprisingly, ties are not entirely unusual in our nation’s highest Court of law. Since 1791, there have been 183 tie votes in the Supreme Court.[6] Sometimes referred to as equally divided votes, ties in the Supreme Court are the result of deadlocks between the majority and minority votes split four-to-four,[7] or on rare occasions, split three-to-three.[8] These ties occur when an even number of Justices are presiding for reasons such as recusal, illness, retirement, or even death.[9] Unlike in baseball, where ties are attempted to be cured with extra innings to avoid an equal final score,[10] currently, in our judicial system, there is no similar procedure in place to mitigate equally divided decisions on the Supreme Court.[11] While a few remedies have been proposed by commentators,[12] legislators,[13] and even Justices themselves,[14] to date none of these proposals have gained any traction or come to fruition.

Therefore, this Comment proposes a possible remedy to the issue of equally decided votes that is somewhat unconventional, but upon closer examination, arguably causes the least amount of revolution within the procedures of the Supreme Court. The proposed solution is simple: whenever there are only eight Justices available to preside over a case, an additional Justice should be withdrawn from the panel. This method of subtracting a Justice rather than adding one aims to prevent equally divided votes, but unlike other methods, does not require increasing funding, implementing new vetting procedures, or delaying justice.

This Comment proceeds in five parts. Part II launches this Comment with a historical analysis of equally divided votes on the Supreme Court, beginning with the first recorded tie vote in 1792. Additionally, Part II provides context for this proposal by reviewing the current practices of the Supreme Court when it comes to equally divided votes, paying special attention to the inconsistencies within these opinions. Part III highlights key cases from the 183 equally decided votes in the Supreme Court through the use of statistical analysis. In doing so, Part III presents the need for a change in the system. Part IV summarizes the alternative remedies that have been offered by other commentators, as well as the issues that each of these alternatives present. Specifically, Part IV focuses on the most common proposal: designation. Lastly, Part V will address my proposed solution of mandatory recusal: removing a Justice of the Supreme Court from a specific matter when there is an even number of Justices on the Court in the case of a recusal, death, or illness.

II. Background

Equally divided votes have been a part of the history of the Supreme Court since its formative years.[15] The Supreme Court dealt with its first tie vote in 1792 in Case of Hayburn.[16] There, the Supreme Court reviewed the Invalid Pension Act of 1792.[17] Designed by Congress to provide financial aid to injured veterans of the Revolutionary War, the Invalid Pension Act required federal circuit courts to determine the eligibility of applicants and submit those decisions to the Secretary of War.[18] The circuit court found that the Act was an attempt by Congress to order federal courts to perform nonjudicial acts and was therefore unconstitutional.[19] The Supreme Court heard oral arguments on the case and then found itself in a three-three split that resulted in a denial of the writ of mandamus.[20] In other words, while only three of six Justices found that Congress’ Act was unconstitutional, the denial of the writ made the Supreme Court’s opinion clear, and a year later Congress revised the Act in response.[21] Thus, while the Supreme Court in Hayburn did not explicitly affirm the lower circuit court’s holding in its language, the outcome of the equally divided vote was essentially the same.[22]

In denying the writ, this Court set in motion what would later become the standard practice in equally divided decisions: an automatic affirmation of the lower court’s decision. Years later, this practice was made more explicit in The Antelope: “Where the Court is equally divided, the decree of the Court below is of course affirmed; so far as the point of division goes.”[23] In doing so, this case set the precedent that an equally divided panel of Supreme Court Justices, without a clear majority, could uphold the legality of a controversial law—in this case by legitimizing the slave trade.[24] Since then, no Supreme Court has acted differently when a tie has arisen, and every equally divided decision has resulted in the automatic affirmation of the lower court’s decision.

Unlike current equally divided cases, however, The Antelope and other contemporaneous tie vote decisions were published with opinions.[25] Even when these opinions were brief, they allowed for some insight into the reasoning behind the Court’s process. For example, in Durant v. Essex Co., Justice Field supported the practice of affirmation in equally divided decisions with references to historical practices in England, using the judges of the King’s Bench and Exchequer Chambers as examples.[26] Durant is significant to this discussion because a central issue the Court attempts to resolve is “[w]hat [is] the effect of an affirmance by an equally divided court?”[27] Here, the Court provides the beginnings of a roadmap for how to apply the stare decisis of equally divided opinions, with Justice Field opining that although the decision is not authoritative on the content of the matter deliberated, “the judgment is as conclusive and binding in every respect upon the parties as if rendered upon the concurrence of all the judges upon every question involved in the case.”[28] In the many years since Durant, the caselaw has remained consistent in this regard, holding that equally divided decisions bind the parties to the suit but have no precedential value.[29]

The Antelope provided some foreshadowing into the eventual hibernation of the equally divided opinion when Justice Marshall opined, “It is unnecessary to state the reasons in support of the affirmative or negative answer to it, because the Court is divided on it, and, consequently, no principle is settled.”[30] Consequently, more recent equally divided decisions tend to feature a single sentence as an opinion: “The judgment is affirmed by an equally divided Court.”[31] However, the lack of standard in what is required for an opinion in this scenario results with some arbitrary, lengthy opinions, allowing Justices who so choose to express their views even if their stances were not in favor of the resulting affirmation of the lower court’s opinion.[32]

Much like the lack of standardization in the format of the opinions issued in these cases, there is disparity amongst the caselaw in whether or not to keep the anonymity of the Justices in an equally divided vote.[33] While the modern trend is to keep the split of the Justices anonymous and name only the Justice that did not participate,[34] cases sometimes include detailed breakdowns of how each Justice voted.[35] Some commentators posit that this omission of each Justice’s vote is an attempt to encourage the adjudication of future cases on the issues and highlight the case’s lack of precedential value.[36] If that proposition is true, it adds to the case for avoiding these types of decisions altogether, especially if they are designed to be largely ignored.

Over time, there has been a shift from three-to-three split votes to four-to-four split votes.[37] Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Supreme Court was set up to have six members, a Chief Justice, and five Associate Justices, who together constituted a quorum.[38] Unsurprisingly, with only six Justices, ties inevitably resulted in a three-three split. As the Court grew in size, so did the number of votes required to tie.[39]

Today, with nine Justices on the Court,[40] most equally divided decisions are likely to result in a four-to-four split. However, since only a quorum of six Justices is required, it is still possible, even if unlikely, that an equally divided vote of three-to-three could persist if three Justices were unavailable.[41] Thus, in summary, an equally divided vote is most likely to be characterized by two features: (1) a four-four split as a result of only eight Justices participating; and (2) a brief, one-sentence affirmation of the lower court’s opinion. Nonetheless, due to the lack of standardization around the issue, anything is possible.

III. Why Ties Matter

Since its establishment in 1789, the Supreme Court has decided more than 28,000 cases, of which only 183 have resulted in ties.[42] In other words, tie votes in the Supreme Court amount to less than one percent of all decisions. Thus, the likely next question on everyone’s mind is probably the following: why does this relatively rare occurrence warrant the following inevitably lengthy discussion?

Here, the small handful of scholars who focus on this niche area of the law have generally posited that the impact of equally divided votes on society is a better determinant of value than quantity.[43] Considering that the Supreme Court’s decisions are intended to have a widespread influence on the activities of the states and their respective branches of government, the strongest standing argument is simply that one equally divided vote is one too many.[44] Thus, whether or not they are statistically notable, when the highest Court in our nation is unable to reach a consensus or majority decision, it has “failed to resolve authoritatively a problem of at least some national importance.”[45] This belief is one that a few Justices themselves seem to support, considering that in some cases, Justices have expressly stated their support of a majority opinion is based solely on an effort to avoid the “limbo of unexplained adjudications” that comes with an equally divided vote.[46] Further, by failing to be decisive, equally divided votes can serve as an “embarrassment” to the Supreme Court as an institution.[47] In summary, the main concerns that are often recounted in the literature are that these decisions: (1) are inefficient; (2) leave legal issues unsettled; (3) make the Supreme Court look bad to the public; and (4) may even subconsciously make Justices less likely to recuse themselves.[48]

Aside from the philosophical question of the importance of these votes, perhaps the best concrete method of establishing their impact is to evaluate them on a case-by-case basis. As discussed earlier, it is the impact of these decisions, rather than their volume, that makes the best case for their need to be made extinct in future adjudication. Unfortunately, looking at each of the 183 equally divided cases would be beyond the scope of this Comment. Thus, a need arises to explore the impact of these decisions with more efficiency, which can be tackled first by using the available data to visualize how these 183 equally divided cases are organized by major issues, and then by addressing the major issues individually.[49]

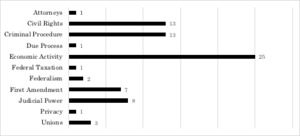

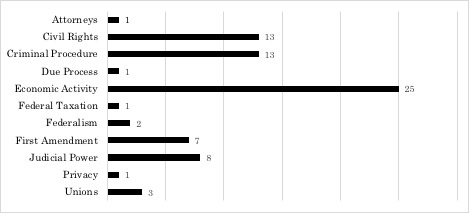

The Supreme Court Database used for this research tags each Supreme Court case within its records by issue, focusing on the subject matter of the controversy rather than its legal basis.[50] In total, there are fourteen major-issue categories, of which equally divided votes have fallen into eleven of those fourteen.[51] Based on the data, it appears that equally divided votes tend to occur most in cases where economic activity, civil rights, and criminal procedure are the key issues.[52] Thus, to continue evaluating the impact of equally divided decisions, a more detailed study of each of these three areas is necessary. In fact, the prevalence of these particular topics alone suggests the impact of tie votes on the Supreme Court.

A. Economic Activity

In the database, the issue marker of economic activity is described as “largely commercial and business related; it includes tort actions and employee actions vis-a-vis employers.”[53] Economic activity was still the most prevalent issue flagged across over 28,000 Supreme Court cases.[54] It is a relatively safe assumption, therefore, that this issue is highly valued to the citizens of our capitalistic society. At the very least, this is an issue that appears commonly in Supreme Court cases.

The most recent case flagged with this marker that resulted in an equally divided decision is Costco Wholesale Corp. v. Omega, where Justice Kagan recused herself due to her former position as Solicitor General.[55] This case arrived in the Supreme Court from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which reversed the trial court and held that Costco’s sale of Omega watches in its stores infringed on Omega’s copyright because the first-sale doctrine, which Costco brought as a defense, did not apply.[56] As a result of the equally divided vote, the Ninth Circuit was affirmed and its ruling against Costco remained in place.[57] Although this Author is in no way an expert on copyright law, it would be imprudent to deny that this decision had a lasting impact on the industry. The Supreme Court decision resulted in a host of academic discussions about patents, copyright, and intellectual property law.[58] While the commentaries take varying stances on the patent issues presented in the case, the consensus amongst most of them is singular: the equally divided vote left the issues “still contentious and unsettled.”[59]

Similarly, in Borden Ranch Partnership v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Justice Kennedy took no part in the decision and the case resulted in an equally divided vote.[60] This decision affirmed the lower court’s holding that deep ripping of wetlands fell under the regulations of the Clean Water Act.[61] Once again, the lack of clarity by the Supreme Court via either a majority vote or opinion caused scholars in the field to posit that after the equally divided vote, the Supreme Court was “leaving the issue in even more doubt than before the Court granted cert.”[62]

Other economic cases that resulted in equally divided votes include activities such as patents,[63] state and local taxation,[64] and antitrust.[65] Thus, it is clear that the Supreme Court’s equally divided votes can have a significant impact on major national industry practices, causing confusion and change without a decisive majority. This impact, coupled with the importance placed on economic rights within our nation, bolsters the need to eliminate future equally divided votes.

B. Civil Rights

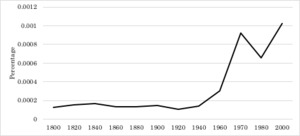

The civil rights marker used to categorize cases is described by the contributors of the database to include “non-First Amendment freedom cases which pertain to classifications based on race (including American Indians), age, indigency, voting, residency, military or handicapped status, gender, and alienage.”[66] The prevalence of the issue of civil rights as a topic of discussion in the media lends support to its importance to society.[67] To better illustrate the importance of this issue, Figure 2 below demonstrates the prevalence of the term “civil rights” in a body of over 5 million books.[68] From this data, it is evident that the overall trend in the usage of the term in the vast library of books compiled by the team of researchers at Google has been trending upwards, especially in the last twenty years.[69] In 2000, the term was at its peak of popularity within the database’s library of words, even surpassing the expected spike in usage during the Civil Rights Movement.[70]

The takeaway here is that important subjects, like civil rights, sometimes get decided by a tied vote at the Supreme Court. Again, this lends support to the necessity for a change in the system, so that future litigation on civil rights issues does not get adjudicated without clear precedent or guidance from the nation’s highest Court.

Beginning with the most recent case flagged with this marker that ended in a tie, which also happens to be the most recent equally divided vote overall, the impact of the Court’s decision in Washington v. United States is of note.[71] There, Justice Kennedy recused himself due to his participation in an earlier phase of the case in 1985.[72] In Washington, the United States brought an action on behalf of Native American tribes against the State of Washington, claiming that the State had violated a fishing treaty.[73] The district court issued an injunction to stop the State from violating the fishing treaty, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed in favor of the tribes.[74] The issues in the case were numerous, ranging from whether the State had actually violated the treaty to whether the injunction intruded onto state government operations and was, therefore, a violation of federalism.[75] Once again, the Supreme Court’s equally divided vote provided no clarity or insight into how the Justices viewed these issues but did serve the purpose of affirming the Ninth Circuit’s decision.[76] As a result, affected state agencies like the Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Department of Transportation, the Department of Natural Resources, and Washington State Parks, must work to unpack the ramifications of this ruling with little guidance from the Supreme Court itself.[77]

Similarly, in United States v. Texas, the Supreme Court’s equally divided decision affirmed a Texas district court’s injunction on a program that would give illegal immigrants legal status and protections.[78] Here, we see the Supreme Court, once again, adjudicating an issue like immigration, a topic of significant importance to many citizens,[79] without a majority ruling or any opinion as guidance. Thus, the Supreme Court in Texas made a decision that impacted the lives of millions with a single sentence.[80] This decision produced a nearly year-long pause on the issue, resolved only when a change in presidency led to the demise of the program altogether, rather than by any clarity on the constitutional nature of the claims.[81]

This is only the tip of the iceberg—the Supreme Court’s equally divided votes in this particular area of the law have created numerous consequences for classes of individuals, like Native Americans,[82] immigrants,[83] and even handicapped children.[84] The argument, thus, is that decisions that affect these important populations should not be made passively due to the technicality of an equal vote, but instead by an active majority.

C. Criminal Procedure

The criminal procedure marker is described as encompassing “the rights of persons accused of crime, except for the due process rights of prisoners.”[85] As with the economic activity and civil rights markers, this area of the law has a far-reaching impact on a variety of issues, including criminal justice,[86] crime rates,[87] and the role of the public at large in the process of criminal adjudication.[88] The decisions courts and legislatures make about the rules that govern how criminal law is enforced can have significant consequences, not only for the parties in the case at hand, but also for society at large.[89]

The most recent case flagged with this marker that ended in a tie is United States v. France, in which Justice Souter took no part in the decision because he was not yet sworn in.[90] In France, the defendant was convicted in Hawaii for “assault with deadly weapon, assault resulting in serious bodily injury, and use of firearm in relation to crime of violence.”[91] The key issue considered by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and subsequently the Supreme Court, was whether it was “reversible error for federal magistrates to conduct jury selection in felony trials.”[92] Specifically, when a “magistrate conducted the voir dire in France’s trial,” the Ninth Circuit reversed her conviction and held that the failure to object to this jury selection did not result in a waiver of the defendant’s right.[93] The Supreme Court, with a four-to-four split, affirmed the Ninth Circuit’s decision to reverse the conviction. Here, the fate of a woman’s life hung in the balance, but the Supreme Court was unable to come to a conclusive decision. The resulting law on this issue is confusing because the highest court in our land never set a precedent, and subsequently, the Ninth Circuit has overruled its own decision.[94]

Similarly, in Ramirez v. Indiana, the Supreme Court’s equally divided vote determined the fate of an individual without more than a sentence in the opinion.[95] In this case, the defendant was convicted of dealing marijuana and raised multiple issues on appeal, including the calculation of his credit time towards this conviction based on being held in jail while awaiting his trial.[96] This pattern of equally divided votes deciding the fate of people on trial for a crime, where their future hangs in the balance, repeats itself in several other criminal procedure cases.[97] This gives rise to the question that is central to this Comment: whether a decision with no precedential value, where an equal number of Justices voted for as did against, should govern a person’s fate.

IV. Current Proposals

By acknowledging that equally divided votes are in fact important, even if they are not bountiful, the natural next question is: what do we do to erase, or at least drastically reduce, their existence? Currently, a number of theories and solutions exist in the academic sphere. Perhaps the simplest is to postpone the trial until all nine Justices can once again participate.[98] Although this method is clearly the easiest to implement quickly, considering it requires no procedural changes to the system, “the length of the delay involved in the stratagem would render it very costly.”[99] Additionally, while this solution may work for certain short-term cases, it does not resolve the issue of recusals, where Justices cannot participate due to a conflict of interest—there, a rehearing would not be fruitful since the reason the Justice was not available is directly linked to the subject matter of the case.

Another relatively simple solution proposed by some scholars is to schedule a rehearing on the matter once there can be full attendance of all nine Justices in the event of an illness or temporary vacancy.[100] Unfortunately, the delays in justice that are attached to this suggestion coupled with its inability to fit every type of case makes it an unappealing solution.[101] Thus, the issue becomes finding a solution that will work for all instances where an even number of Justices presides over the Supreme Court, whether as a result of death, illness, or recusal.

To date, the most popular and comprehensive solution has been that of designation,[102] specifically through the use of retired Supreme Court Justices.[103] The idea is simple: ask retired Justices, who once served on the Supreme Court, to step back into their role and fill vacant spots in the event of a recusal, death, illness, or other emergency event.[104] This solution is premised on the idea that a Justice retains his office when he retires from active service.[105] The argument in defense of this particular solution is founded largely on its practicality and efficiency: “Retired Justices are a valuable human resource—however small and elite the group making up that resource might be—and one that is underutilized under the existing statutory scheme.”[106] The comparison is often drawn by supporters of this proposal to retirees in other professions, such as doctors, who in their retirement usually retain the ability to reengage in the profession as a consultant.[107] Thus, designation often boils down to the question of “who better to fill the role of a vacant Supreme Court Justice than a former Justice, with the knowledge and expertise of the role’s responsibilities?”

Unfortunately, as it currently stands, this solution is barred by federal law, which allows the designation of Justices of the Supreme Court to circuit courts but expressly prohibits the opposite: “No such designation or assignment shall be made to the Supreme Court.”[108] Until this statute is amended, this solution, no matter how effective, cannot proceed. Additionally, while the Constitution itself does not speak as explicitly on the subject, scholars have argued that since Article III creates a requirement of “one supreme court,”[109] having a rotating roster of Justices would actually create “not . . . one Supreme Court, but several different Courts.”[110] While this formalist argument might eventually be worked around, as it stands, the legality of designation as a whole is still unclear, which lends to the current impracticability of this solution.

Beyond the legality of this proposal, there are other problems. First, designation comes with the possibility of undermining the authority of the sitting Justices.[111] By coming out of retirement and straight onto the highest Court in the nation, designation may cause distrust in the Court by the American people.[112] Questions might arise about the ability of a retired Justice, who at some point chose to resign from the Court, to adjudicate a major issue of law after being out of practice. Additionally, while this solution may result in breaking ties, it might simultaneously empower a single Justice to serve as a swing-vote, resulting in the development of a host of other political problems. The issue becomes how to select which judge comes out of retirement.[113] Here, once again, this solution might inadvertently increase the politicization of the courts.[114]

Last but not least, the inevitable issue arises of what to do when there is no living, retired Justice to designate in the place of an absent Justice. Currently, there are three living retired Justices.[115] However, it has not always been the case that a retired Justice is alive and available for a possible designation.[116] Thus, the solution is by no means fool-proof, and seemingly produces more questions than answers. For this reason, I propose an alternative that addresses the gaps in the other current proposals: mandatory recusal.

V. Mandatory Recusal

The underlying cause of equally divided votes on the Supreme Court is the existence of an even number of presiding Justices, whether it be a three-to-three vote or a four-to-four vote. Thus, many proposed solutions attempt to either replace the missing Justice or wait for the vacancy to pass so that the total number of presiding Justices can be brought back up to an odd number of nine.[117] However, I argue that an even simpler solution exists: one of subtraction instead of substitution. Below, I outline a model for implementing a mandatory recusal method, as well as possible concerns that arise with the proposed solution.

The mandatory recusal solution is based on the simple fact that seven Justices are just as much of an odd number as nine Justices. Therefore, having seven Justices would be equally effective in negating the possibility of an equally divided vote. Thus, my proposal is that, whenever a Justice has to recuse his or herself due to a conflict or is unable to be in attendance due to sickness or injury, another Justice should be required to abstain from participating in the case to ensure an odd number of Justices presides, thereby avoiding the potential for an equally divided vote.

Of course, the natural question here is which Justice should be required to abstain? The mandatory recusals could be handled in a variety of ways, such as with a schedule or rotation model, a lottery, or even simply by requiring the most recent addition to the bench to step down for that particular case. Here, the concern is similar to that of designation: to ensure that the mandatory recusal process does not become politicized.[118] Depending on which method of selecting the abstaining Justice is chosen, the results may lead to bias on the bench.[119]

To avoid this, I suggest moving forward with a lottery approach at the start of the proceedings. In essence, this would involve one Justice, randomly chosen, to recuse herself in order to ensure an odd number of Justices could preside. This way, there is no question about who will abstain, and fairness is built into the system by leaving the abstaining Justice to chance. While the exact methods for this random selection are beyond the scope of this Comment, it is likely that the advent of technological advances will provide a simple solution to ensuring a fair, consistent approach to the selection method.[120]

Unlike a rotational model, which requires Justices to take turns recusing themselves based on some predetermined schedule, the benefit of a lottery system is that there is no way for parties to game the system. In a rotation system, a party might wait to bring a suit or use delaying tactics to time the suit for the Justice they wanted to abstain based on the schedule. In a lottery system that takes place when the case begins, there is a slim likelihood parties could impact the choice or adjust their strategy to ensure they have the most favorable Court.[121] Additionally, a rotational model is inherently flawed because it attempts to predict a fair and consistent schedule to resolve an arbitrary set of events that results in the Supreme Court being one Justice short of a full bench.

On the other hand, a seniority approach of always asking the newest Justice to abstain allows some level of consistency, at least for as long as a Justice remains the most recent nomination to the bench. However, this method will likely result in frustration by society and political officials due to a consistent requirement for the newest Justice to abstain from participating in cases. After all, it takes a great deal of effort to get a Supreme Court Justice appointed and confirmed,[122] and if after putting in all that effort the new Justice has to simply sit out every time a tie might arise, what was the point of even getting that Justice confirmed? Here, I would argue that, while less consistent, a random selection at the beginning of oral arguments ensures that all Justices have an equal chance to adjudicate and avoids making the newest Justice essentially a lame duck.

An additional method of selection mentioned might be to choose the Justice with the least amount of expertise on the matter to abstain.[123] For example, in the Washington case, perhaps the Justice who knew the least about Native American treaties might have been asked to step down, allowing those with more expertise to adjudicate on the issue.[124] However, that could lead to a host of new issues, such as how a decision is made on who is the least experienced, or an increased lack of confidence in the Justice moving forward on other matters if they have been deemed to be not an expert on a certain issue. For these reasons, I still find the lottery method of mandatory recusal to be the least problematic.

Of course, mandatory recusal comes with its own set of problems, the most pressing of which is what to do when there are only six Justices available to adjudicate. While six Justices could result in an equally divided result, recusal of an additional Justice to avoid the result would result in a lack of a quorum.[125] First, it is important to note that this is highly unlikely, since three-to-three ties have not been an issue for the Supreme Court in decades.[126] It would require three Justices, rather than one, to be unavailable at the same time, which seems increasingly unlikely to occur. In that situation, I would recommend proceeding with a more conservative strategy of waiting for a rehearing once at least one of the Justices is able to return.[127] Although this brings forward earlier concerns of delaying justice and increasing litigation costs, as discussed earlier, it is unlikely to be necessary for implementation.[128]

While diving further into the nitty-gritty of implementing this system is outside of the scope of this Comment, it is unlikely that the details would be any more complicated than the other proposals.[129] While every proposal has its own set of problematic consequences, this solution by subtraction rather than substitution seems to provide the cleanest, most efficient approach. Thus, when it comes to finding a solution for equally divided votes in the Supreme Court, less is more.[130]

VI. Conclusion

Regardless of their small number, the types of cases that turn on an equally divided vote lends credibility to the notion that ties in the Supreme Court are a thing of concern. Over the course of our nation’s judicial history, important decisions about economic activity, civil rights, and criminal procedure have been formed by an undecided panel of Justices who could not reach a singular conclusion.[131] Unfortunately, as it currently stands, there is no procedure or process in place to resolve tied votes.[132] Instead, scholars continue to posit one solution after another, each one with its own set of concerns and challenges. While designation is, so far, the most successful solution, purely in that it has been advocated for by Justices themselves and even progressed to reality as a proposed bill, it is problematic and likely unconstitutional.[133]

To combat the issues that arise in other solutions, I offer, in my opinion, a more elegant option: mandatory recusal. By requiring a Justice to abstain from a matter whenever an even number of eight Justices is on the bench, we can bring the count back to an odd number and summarily avoid a tie. While further studies of the best methods of implementing mandatory recusal are warranted, I believe that this proposal can succeed where others have not by avoiding constitutional concerns, undue delays, and complicated substitution methods.

Aditi Deal

See Rick Porter, TV Ratings: World Series Game 7 Draws 23M Viewers for Fox, Hollywood Rep. (Oct. 31, 2019), https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/world-series-game-7-tv-ratings-wednesday-oct-30-2019-1251424 [https://perma.cc/98WL-5Q7V].

The Author would like to use this opportunity to share her support of the Houston Astros, who in her opinion, were the nation’s best baseball team of 2019 regardless of the World Series’ unfortunate outcome. See generally World Series, Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/sports/World-Series [https://perma.cc/N9QV-96JD] (last visited Sept. 22, 2020).

Pam C. Corley et al., The Puzzle of Unanimity: Consensus on the United States Supreme Court 2 (2013) (describing the curious circumstances where all Justices agree unanimously when, in contrast, “split decisions are [more] understandable given that the setting in which the [J]ustices operate points toward division rather than consensus”).

See Ruth Bader Ginsburg Death: What Is the US Supreme Court?, BBC News (Sept. 19, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-38707720 [https://perma.cc/K3P9-H8GA] (describing the importance of the Supreme Court and Supreme Court nominations). See generally About the Supreme Court, U.S. Cts., https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/about [https://perma.cc/8XK7-BQX5] (last visited May 10, 2020) (describing the impact of the Supreme Court on society by listing multiple facets of its “very important role in our constitutional system of government”).

About the Supreme Court, supra note 4.

See The Supreme Court Database, Wash. Univ. L., http://scdb.wustl.edu/analysis.php [https://perma.cc/WN4Y-HSCX] (last visited Sept. 28, 2020) (select “Modern Data” tab; then select “equally divided vote” filter; then click “analyze”; then select “Legacy Data” tab; then select “equally divided vote” filter; then click “analyze”; then add together the number of results from both queries); infra text accompanying note 42. This statistic is a result of a search that was run on the website’s Supreme Court data analysis tool, which allows for filtration of cases by a variety of variables such as date, decision type, disposition, etc. Here, the cases were filtered for the specific variable of “equally divided vote[s],” which produced a total of 183 results.

See, e.g., Friedrichs v. Cal. Tchrs. Ass’n, 136 S. Ct. 1083 (2016) (affirming the lower court’s judgment by a four-four equally divided court); Adam Liptak, Victory for Unions as Supreme Court, Scalia Gone, Ties 4-4, N.Y. Times (Mar. 29, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/30/us/politics/friedrichs-v-california-teachers-association-union-fees-supreme-court-ruling.html [https://perma.cc/UHR9-BKBS] (describing that the vacancy on the Court at the time of the Friedrichs case was a result of Justice Scalia’s demise).

See, e.g., Reagan v. Abourezk, 484 U.S. 1, 2 (1987) (affirming the judgment in the lower court by a three-three equally divided court due to Justice Blackmun and Justice Scalia’s recusals, as well as Justice Powell’s recent retirement from the Court); Stuart Taylor Jr., Powell Leaves High Court; Took Key Role on Abortion and on Affirmative Action, N.Y. Times (June 27, 1987), https://www.nytimes.com/1987/06/27/us/powell-leaves-high-court-took-key-role-on-abortion-and-on-affirmative-action.html [https://perma.cc/8S76-VS6F].

See, e.g., William L. Reynolds & Gordon G. Young, Equal Divisions in the Supreme Court: History, Problems, and Proposals, 62 N.C. L. Rev. 29, 36 (1983).

See Off. Playing Rules Comm., Official Baseball Rules 87 (2019), https://img.mlbstatic.com/mlb-images/image/upload/mlb/ub08blsefk8wkkd2oemz.pdf [https://perma.cc/4NQ6-KKEE] (“If the score is tied after nine completed innings play shall continue until (1) the visiting team has scored more total runs than the home team at the end of a completed inning, or (2) the home team scores the winning run in an uncompleted inning.”).

See generally Sup. Ct. of the U.S., Rules of the Supreme Court of the United States (2019), https://www.supremecourt.gov/ctrules/2019RulesoftheCourt.pdf [https://perma.cc/5UNR-5ZH3] (showing a marked lack of rules about equally divided votes, recusals, or vacancies).

See Reynolds & Young, supra note 9, at 35–41 (discussing various proposals such as postponement of the case and rehearing the case once all justices are once again present).

See As Congress Considers Using Retired Justices, Most States Already Do, Nat’l Ctr. for State Cts. (Sept. 30, 2010), https://web.archive.org/web/20200331123944/https://www.ncsc.org/Newsroom/Backgrounder/2010/Retired-Justices.aspx [https://perma.cc/AHU4-P8A3] (describing Senator Patrick Leahy’s proposal to “allow a retired Supreme Court [J]ustice to return to the bench temporarily in cases where an active justice has recused”).

See Lisa T. McElroy & Michael C. Dorf, Coming off the Bench: Legal and Policy Implications of Proposals to Allow Retired Justices to Sit by Designation on the Supreme Court, 61 Duke L.J. 81, 90–91, 90 n.37 (2011) (describing Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice John Paul Stevens’s approach of having retired Justices come back on active duty in such cases).

See Case of Hayburn, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 408 (1792). The Supreme Court first assembled in 1790. See History and Traditions, Sup. Ct. U.S., https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/historyandtraditions.aspx [https://perma.cc/3UQC-XR9T] (last visited Mar. 9, 2020).

Hayburn, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) at 408; see also Ryan Black & Lee Epstein, Recusals and the “Problem” of an Equally Divided Supreme Court, 7 J. App. Prac. & Process 75, 81 & n.26 (2005).

Hayburn, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) at 408 (“T[his] was a motion for a mandamus, to be directed to the circuit court for the district of Pennsylvania, commanding the said court to proceed in a certain petition of William Hayburn, who had applied to be put on the pension list of the United States, as an invalid pensioner.”).

Max Farrand, The First Hayburn Case, 1792, 13 Am. Hist. Rev. 281, 281 (1908). Specifically, the Act directed that commissioned officers and noncommissioned, disabled officers, “shall be entitled to be placed on the pension list of the United States . . . and shall also be allowed such farther sum for the arrears of pension . . . as the circuit court of the district, in which they respectively reside, may think just.” Invalid Pension Act, ch. 11, § 2, 1 Stat. 243, 244 (1792).

Hayburn, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) at 408 n.* (“[T]he business directed by this act is not of a judicial nature. It forms no part of the power vested by the constitution in the courts of the United States; the circuit court must, consequently, have proceeded without constitutional authority.”).

Maeva Marcus & Robert Teir, Hayburn’s Case*: A Misinterpretation of Precedent*, 1988 Wis. L. Rev. 527, 528, 538 (1988) (“Although the Court heard oral argument on the substantive issue, it never rendered a decision on the merits.”).

An Act to Regulate Claims to Invalid Pensions, ch. 17, §§ 1–2, 1 Stat. 324 (1793) (effectively removing the role of the circuit courts altogether from the process and resolving the equally divided court’s tie in favor of the separation of powers).

Hayburn, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) at 408; Marcus & Teir, supra note 20, at 539. In fact, even though this case did not explicitly decide the issue at hand, it has been cited by numerous cases since “in support of judicial restraint.” Id. at 528, 539; see also Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 123–24 (1975) (citing Hayburn as support for prohibiting Congress from appointing officers of the executive branch); Larson v. Valente, 456 U.S. 228, 264 (1982) (Rehnquist, J., dissenting) (citing Hayburn in defense of prohibiting the Supreme Court from giving advisory opinions).

The Antelope, 23 U.S. (10 Wheat.) 66, 66–67 (1825) (affirming the Circuit Court of Georgia).

Id. The Antelope was a slave ship carrying 281 living captives. See Jonathan M. Bryant, “By the Law of Nature, All Men Are Free”: Francis Scott Key and the Slave Ship Antelope, Salon (July 11, 2015, 7:59 PM), https://www.salon.com/2015/07/11/“by_the_law_of_nature_all_men_are_free”_francis_scott_key_and_the_case_of_the_slave_ship_antelope/ [https://perma.cc/9C7G-XYX3]. Thus, when the ship was captured and the question arose of what to do with these captives, the Court had to decide whether to treat them as humans, and therefore return them to their home countries, or as property, and therefore allow them to continue in the possession of the owners of the ships. Id. Here, with a tie vote, the Supreme Court made a decision that was instrumental in the development of slave history in this nation by ruling slaves as property, not persons. Id.; Antelope, 23 U.S. (10 Wheat.) at 67.

See, e.g., Etting v. U.S. Bank, 24 U.S. (11 Wheat.) 59, 59–65 (1826) (summarizing in an opinion of more than 3,000 words the facts of the case and an analysis of the Circuit Court of Maryland’s reasoning).

Durant v. Essex Co., 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 107, 109, 111–12 (1868) (dealing with whether a bill attempting to hold a company liable was erroneously dismissed by the Circuit Court of Massachusetts and whether that dismissal was a bar to any new suits on the matter).

Id. at 108.

Id. at 109, 113. Here, Justice Field supports the idea that a review of a lower court’s opinion by the Supreme Court operates under the assumption of a motion to reverse, “and if that fails, the judgment, or decree, necessarily stands.” Id. at 109, 112 (citation omitted). In doing so, Justice Field essentially insinuates that a tie vote is a “failure” by the Supreme Court to reverse the lower court decision. Id.

See, e.g., Exxon Shipping Co. v. Baker, 554 U.S. 471, 471 (2008) (“Because the Court is equally divided on whether maritime law allows corporate liability for punitive damages based on the acts of managerial agents, it leaves the Ninth Circuit’s opinion undisturbed in this respect. Of course, this disposition is not precedential on the derivative liability question.”); Neil v. Biggers, 409 U.S. 188, 192 (1972) (“Nor is an affirmance by an equally divided Court entitled to precedential weight.”); United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203, 216 (1942) (“[T]he lack of an agreement by a majority of the Court on the principles of law involved prevents it from being an authoritative determination for other cases.”).

The Antelope, 23 U.S. (10 Wheat.) 66, 126 (1825).

See, e.g., Washington v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 1832, 1833 (2018). Since 2010, all equally divided votes have used this single-sentence opinion rather than a lengthier discussion of rationale. See The Supreme Court Database, supra note 6. Each equally divided decision from 2010 to 2018 was pulled from this database and then cross-referenced with Westlaw to come to this conclusion. Id.

See, e.g., Standard Indus., Inc. v. Tigrett Indus., Inc., 397 U.S. 586 (1970) (where Justice Black provides a dissent with Justice Douglas joining).

This is a pattern in equally divided cases—the lack of standards around how these cases function is a key part of the issues these types of cases bring about in our judicial system.

See, e.g., Washington, 138 S. Ct. at 1833 (“Justice Kennedy took no part in the decision of this case.”).

See, e.g., Ohio ex rel. Eaton v. Price, 364 U.S. 263 (1960) (“Mr. Justice Stewart took no part in the consideration or decision of this case. Mr. Justice Brennan, with whom The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Black, and Mr. Justice Douglas join.”).

See Justin Pidot, Tie Votes in the Supreme Court, 101 Minn. L. Rev. 245, 254 (2016); Ohio, 364 U.S. at 264 (“[P]reventing the identification of the Justices holding the differing views as to the issue . . . may well enable the next case presenting it to be approached with less commitment.”).

The last three-three equally divided vote on the Supreme Court was in 1987, which affirmed by equally divided vote the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia. Reagan v. Abourezk, 484 U.S. 1 (1987). At issue in the case was the scope of the Secretary of State’s authority to deny visas, specifically to “aliens who wish to visit this country in response to invitations from United States citizens and residents to attend meetings or address audiences here.” Abourezk v. Reagan, 785 F.2d 1043, 1047 (D.C. Cir. 1986), aff’d , 484 U.S. 1 (1987). By affirming, the Supreme Court’s decision was one in favor of remanding for further proceedings and reversing the granting of a motion of summary judgment for the government holding the specific visa denials constitutional. Id.; see also infra note 41.

An Act to Establish the Judicial Courts of the United States, ch. 20, § 1, 1 Stat. 73, 73 (1789) (“[T]he Supreme Court of the United States shall consist of a chief justice and five associate justices, any four of whom shall be a quorum.”). This Act was passed shortly after the Constitution, which sets neither the size of the Supreme Court nor specifies any positions therein. U.S. Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 2.

Congress has made many revisions to the number of Justices who should sit on the Supreme Court. See The Court as an Institution, Sup. Ct. U.S., https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/institution.aspx [https://perma.cc/QKK8-JSFH] (last visited Jan. 12, 2020). Today, the number rests at nine. See An Act to establish the Judicial Courts of the United States, ch. 22, § 1, 16 Stat. 44, 44 (1869) (“[T]he Supreme Court of the United States shall hereafter consist of the Chief Justice of the United States and eight associate justices, any six of whom shall constitute a quorum.”).

See Current Members, Sup. Ct. U.S., https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx [https://perma.cc/V8UD-NTM6] (last visited Mar. 9, 2020).

Reagan provides a modern example, where almost a century after the implementation of an expanded court of nine Justices, a three-three equally divided vote arose. Reagan, 484 U.S. at 2.

See The Supreme Court Database, supra note 6. In order to arrive at these numbers, results from both the traditional and modern datasets housed within the database were separately analyzed and then added together. Id. The traditional dataset houses information about Supreme Court cases from 1791 to 1945, while the modern dataset completes the record with cases from 1946 to 2018. Id. Thus, there are some cases that have not been analyzed (before 1791). However, since the first known tie occurred in 1792, it is unlikely that this gap will significantly impact this Comment’s evaluation of equally divided votes as whole. See Case of Hayburn, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 408 (1792).

See Reynolds & Young, supra note 9, at 30–33. The authors emphasize the frequency of these decisions, noting that between 1925 and 1982 there were an average of two equally divided votes per year. Id. at 30.

See McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 95 (“[I]t could be argued that even one 4–4 split can be harmful.”). Here, the authors note that if the goal of a writ of certiorari is to resolve an issue that the nation finds important, then “failure to resolve the issue would be harmful, regardless of the outcome.” Id. They proceed to couch this assertion with two points: first, issues that are important are likely to recur, thus giving the Supreme Court another stab at a concrete resolution, and second, a substitute Justice is unlikely to be effective. Id. at 95–96. However, the second point is irrelevant to this Comment’s proposed solution, which does not depend on the use of a substitute Justice, but instead, relies on subtracting a Justice from the panel.

See Reynolds & Young, supra note 9, at 31.

Id. at 32 n.10 (citing Inman v. Balt. & Ohio R.R., 361 U.S. 138, 141 (1959) (Frankfurter, J., concurring)).

See Black & Epstein, supra note 16, at 82–83.

See Pidot, supra note 36, at 287–95.

See The Supreme Court Database, supra note 6.

Supreme Court Database Code Book, Wash. Univ. L. 45 (Sept. 12, 2019), http://scdb.wustl.edu/_brickFiles/2019_01/SCDB_2019_01_codebook.pdf [https://perma.cc/G7X6-8HKG].

Id. at 50. (showing that the omitted issues from this analysis with no equally divided votes are interstate relations, miscellaneous, and private law). For the purposes of analyzing the issues further, these tags would need further evaluation, such as the current purpose they serve “to categorize the case from a public policy standpoint” rather than summarize everything the case itself discusses. Id. at 45. However, for our purposes, these issues provide a simple structure for evaluating their impact.

Even within the database as a whole, the three largest issues decided by the Supreme Court as a whole are: economic activity, civil rights, and criminal procedure. See id. at 49. Thus, it is important to note that the “contents of these issues are both over- and under-specified” in an effort to efficiently categorize all 28,000 cases. Id.

Id. at 47 (using the definitions provided by the Online Codebook).

See The Supreme Court Database, supra note 6 (tabulating both Legacy and Modern Data to arrive at these numbers).

See Costco Wholesale Corp. v. Omega, S.A., 562 U.S. 40 (2010). This case came to be during Justice Kagan’s first term, from October 2010 to June 2011, where Justice Kagan recused herself from twenty-eight of the seventy-five cases that the Supreme Court presided over. Stephen Wermiel, SCOTUS for Law Students (Sponsored by Bloomberg Law): Justice Kagan’s Recusals, SCOTUSblog (Oct. 9, 2012, 9:50 PM), https://www.scotusblog.com/2012/10/scotus-for-law-students-sponsored-by-bloomberg-law-justice-kagans-recusals/ [https://perma.cc/962L-BMFU]. Almost every time she recused herself, the Court operated with eight Justices, presenting a number of opportunities for the possibility of an equally divided vote. Id.

See Omega S.A. v. Costco Wholesale Corp., 541 F.3d 982 (9th Cir. 2008). The first-sale doctrine essentially says that if someone purchases a copyrighted work, they can later sell it without the copyright holder’s permission. 17 U.S.C. § 109. The central issue was whether the first-sale doctrine applied to imported, copyrighted products that were produced in foreign nations. Omega, 541 F.3d at 983.

Omega, 541 F.3d at 983 (affirming the district court’s construction that the first-sale doctrine provides “no defense to an infringement action under §§ 106(3) and 602(a) that involves (1) foreign-made, [nonpirated] copies of a U.S.-copyrighted work, (2) unless those same copies have already been sold in the United States with the copyright owner’s authority”).

See, e.g., Thomas J. Bacon, Caveat Bibliotheca: The First Sale Doctrine and the Future of Libraries After Omega v. Costco, 11 J. Marshall Rev. Intell. Prop. L. 414, 426–27, 438 (2011); Mark Jansen, Applying Copyright Theory to Secondary Markets: An Analysis of the Future of 17 U.S.C. § 109(a) Pursuant to Costco Wholesale Corp. v. Omega S.A., 28 Santa Clara Comput. & High Tech. L.J. 143, 161, 166–67 (2011).

Bacon, supra note 58, at 426.

Borden Ranch P’Ship v. U.S. Army Corps of Eng’rs, 537 U.S. 99, 100 (2002). In this case, Justice Kennedy recused himself because he knew one of the parties personally. See Donald Kennedy & Brooks Hanson, What’s a Wetland, Anyhow?, Science (Aug. 25, 2006), https://science.sciencemag.org/content/313/5790/1019 [https://perma.cc/KP75-KNGJ].

See Borden Ranch P’ship v. U.S. Army Corps of Eng’rs, 261 F.3d 810, 815, 816 (9th Cir. 2001), aff’d, 537 U.S. 99 (2002) (discussing the case where a farmer, Tsakopoulos, used long metal shanks to convert grazing land into a vineyard and holding that such activity would require a Clean Water Act Section 404 permit and was not included as a “[n]ormal [f]arming [activity] [e]xception”).

William Funk, Supreme Court News, Admin. & Regul. L. News, Spring 2003, at 16, 16; see also Martha L. Noble & Thomas P. Redick, Agricultural Management: 2002 Annual Report, in Environment, Energy, and Resources law: The Year in Review 2002, at 166, 169 (2003) (“The one-sentence opinion issued by an equally divided court does little to clarify the scope of the normal farming exemption.”).

See Lotus Dev. Corp. v. Borland Int’l, Inc., 516 U.S. 233, 233 (1996) (affirming by equally divided vote the First Circuit’s decision that the menu command hierarchy in a spreadsheet program was uncopyrightable as a “method of operation”), aff’g 49 F.3d 807 (1st Cir. 1995). Justice Stevens took no part in the decision, leaving the Court with eight Justices and, therefore, vulnerable to an equally divided vote. Id. at 234.

See Ford Motor Credit Co. v. Dep’t of Revenue, State of Fla., 500 U.S. 172 (1991) (affirming by an equally divided vote a Florida District Court’s decision that the Intangible Personal Property Tax Act’s application to contracts to finance the sale of a car was not a violation of the Commerce Clause). Justice O’Connor took no part in the decision. Id.

See Mich. Citizens for an Indep. Press v. Thornburgh, 493 U.S. 38 (1989) (affirming by an equally divided vote the District of Columbia Court of Appeal’s support of the Attorney General’s decision to approve a joint operating agreement as an antitrust exemption under the Newspaper Preservation Act). Justice White did not participate in the decision. Id. at 39.

See The Supreme Court Database Code Book, supra note 50, at 46 (explaining the classification of Supreme Court civil rights cases). First Amendment cases are their own, separate category, although some of those cases do include civil rights issues. Id.

In fact, major news sources even dedicate entire sections of their publications to the topic alone. See, e.g., Civil Rights, N.Y. Times, https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/civil-rights [https://perma.cc/6W85-KF6F] (last visited Jan. 12, 2020); Civil Rights, U.S. News, https://www.usnews.com/topics/subjects/civil-rights [permalink unavailable] (last visited Jan. 12, 2020); Civil Rights, HuffPost, https://www.huffpost.com/news/topic/civil-rights [https://perma.cc/UU69-9KG8] (last visited Jan. 12, 2020).

See Jean-Baptiste Michel et al., Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books, 331 Science 176, 176–77 (2011) (“corpus of 5,195,769 digitized books” as of 2011). The Ngram tool displays a graph of the phrase’s frequency over the selected years, allowing for the identification of trends over time. See id. (providing the search term “slavery” as an example, which resulted in a peak during the Civil War, then again during the Civil Rights movement).

Id. at 177. The tool essentially allows a user to look at “linguistic and cultural trends in this material, by connecting text and metadata (year, language information).” Magnus Breder Birkenes et al., From Digital Library to N-Grams: NB N-Gram, Proc. of the 20th Nordic Conf. of Computational Linguistics 293, 293 (2015).

James N. Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America 72 (2005) (“media focused more and more on issues of civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s.”). Although the spike in the chart appears to be a bit delayed from this timeline, it is likely that books were published about the subject matter with a delay. See id.

Washington v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 1832 (2018).

Letter from Scott S. Harris, Clerk of the Ct., Sup. Ct. of the U.S., to Noah Guzzo Purcell, Solic. Gen., William M. Jay, Goodwin Procter LLP, & Noel J. Francisco, U.S. Dep’t of Just., (Mar. 23, 2018), https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/17/17-269/39869/20180323153617321_Recusal Letter in No. 17-269.pdf [https://perma.cc/2F49-JEUM] (informing counselors on the case of Justice Kennedy’s recusal).

See United States v. Washington, 853 F.3d 946, 954 (9th Cir. 2017), cert. granted, 138 S. Ct. 735 (2018).

Id.

Id. at 971–72.

Washington, 138 S. Ct. at 1832.

Jill Dvorkin, The Culverts Case: An Overview and Potential Implications for Local Governments, MRSC (June 20, 2018), http://mrsc.org/Culverts-Case-Implications-Local-Governments.aspx [https://perma.cc/6B6H-NMBX]. As it stands, scholars continue to unpack the implications for local governments, including “how their infrastructure and land use policies may affect . . . fish.” Id.

United States v. Texas, 136 S. Ct. 2271, 2272 (2016). The Supreme Court at this time sat with only eight Justices due to the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February of 2016. Supreme Court Timeline: From Scalia’s Death to Garland to Gorsuch, USA Today (Jan. 31, 2017, 8:55 PM), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/01/31/timeline-of-events-after-the-death-of-justice-antonin-scalia/97299392/ [https://perma.cc/S74K-ATXA]. The Supreme Court was not back to a full nine Justices until Neil Gorsuch took Scalia’s place in April of 2017, more than a year later. Tessa Berenson, How Neil Gorsuch’s Confirmation Fight Changed Politics, Time (Apr. 7, 2017, 11:58 AM), https://time.com/4730746/neil-gorsuch-confirmed-supreme-court-year/ [https://perma.cc/DD5F-TG4V].

See, e.g., Jeffrey M. Jones, Mentions of Immigration as Top Problem Surpass Record High, Gallup (July 23, 2019), https://news.gallup.com/poll/261500/mentions-immigration-top-problem-surpass-record-high.aspx [https://perma.cc/ZY5E-KFQ2] (describing how immigration was listed as the most important problem facing the United States by 27% of all Americans polled, a number that only a handful of issues have ever eclipsed since 2001).

See Texas, 136 S. Ct. at 2272 (affirming the district court’s grant of an injunction against the Department of Homeland Security and other United States Officials from implementing the “Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents” (DAPA) program). The program was “designed to provide legal presence to over four million individuals who are currently in the country illegally, and would enable these individuals to obtain a variety of both state and federal benefits.” Texas v. United States, 86 F. Supp. 3d 591, 604 (S.D. Tex. 2015), aff’d, 809 F.3d 134 (5th Cir. 2015).

See Aria Bendix, Trump Rolls Back DAPA, Atlantic (June 16, 2017), https://www.theatlantic.com/news/archive/2017/06/trump-rolls-back-dapa-program/530571/ [https://perma.cc/CM6F-GZHM].

See, e.g., Washington v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 1833 (2018).

See, e.g., Texas, 136 S. Ct. at 2272.

See Bd. of Educ. v. Tom F., 552 U.S. 1, 2 (2007) (where Justice Kennedy took no part in a decision that affirmed the Second Circuit’s decision vacating an order by the district court that denied parents of a disabled child a tuition reimbursement).

See The Supreme Court Database Codebook, supra note 50 (explaining the classification of Supreme Court criminal procedure cases).

See William J. Stuntz, The Uneasy Relationship Between Criminal Procedure and Criminal Justice, 107 Yale L.J. 1, 3–4 (1997) (describing the impacts of criminal procedure on the criminal justice system as a whole).

See Paul Rubin & Raymond A. Atkins, Effects of Criminal Procedure on Crime Rates: Mapping out the Consequences of the Exclusionary Rule 6, 15–16 (The Indep. Inst., Working Paper No. 9, 1999) (describing the impacts of a Supreme Court case on crime rate). An argument is made that the Supreme Court’s ruling in specific cases “caused detectable increases in crime rates.” Id. at 23.

See Jocelyn Simonson, The Place of “The People” in Criminal Procedure, 119 Colum. L. Rev. 249, 261 (2019) (describing the impacts of criminal procedure on the role that the public plays in the criminal system). Simonson posits that when the judiciary or legislature makes decisions, like who can post bail or who can serve on a jury, they effectively control how the public can interact with the criminal system. Id. at 261–62. Thus, the impact is greater than just on the defendants alone.

See Stuntz, supra note 86, at 28 (describing the connection between criminal procedure and the lack of access to justice for poor minorities).

See United States v. France, 498 U.S. 335 (1991) (where Justice Souter did not participate in the decision). Arguments for this case were on October 2, 1990, and Justice Souter was not sworn in until six days later, on October 8, 1990. See Justice Souter Swearing-in, C-Span (Oct. 8, 1990), https://www.c-span.org/video/?14422-1/justice-souter-swearing [https://perma.cc/7C4X-NFZR].

See United States v. France, 886 F.2d 223, 223–24 (9th Cir. 1989), aff’d, 498 U.S. 335 (1991).

Id. at 224.

Id. at 224, 228.

See United States v. Keys, 133 F.3d 1282, 1287 (9th Cir. 1998) (holding that a “failure to object to a jury instruction-even where the law of the circuit is clear-will entitle a defendant to have an error claimed for the first time on appeal”).

Ramirez v. Indiana, 471 U.S. 147, 147 (1985). It is worth noting that Justice Powell did not take part in the delivery of the famous line: “The judgment is affirmed by an equally divided Court.” Id.

Ramirez v. State, 455 N.E.2d 609, 617 (Ind. Ct. App. 1983), aff’d sub nom., Ramirez v. Indiana, 471 U.S. 147 (1985).

See, e.g., Flores-Villar v. United States, 564 U.S. 210 (2011) (affirming by equally divided vote the Ninth Circuit’s decision to uphold a conviction).

Reynolds & Young, supra note 9, at 35–36 (suggesting a deadlocked case could be postponed in some cases).

Id. at 36.

Id. at 37 (describing a number of instances where the Supreme Court has granted a rehearing in circumstances that prevented a deadlock but qualifying that “a large number of equal divisions will not be amenable to a rehearing solution”).

See id. (suggesting that “speedy justice would suffer” even if the process for rehearing cases was clearly defined, which at present, it is not).

Id. at 38 (describing designation as having “a judge from another court to hear the case and break the deadlock”). This technique is used in a number of state supreme courts for this same issue of avoiding equally divided votes, including Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, Hawaii, and New Jersey. See id. at 38 n.49.

This particular solution is supported by many scholars, and even a couple of Justices. See McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 83, 90 & n.37 (describing Rehnquist and Stevens’s support of this approach). Additionally, this solution was once brought before Congress by Senator Leahy. See National Center for State Courts, supra note 13. It is important to note, however, that this proposal has never been enacted, and the bill “died in a previous Congress.” See S. 3871 (111th): A Bill to Amend Chapter 13 of Title 28, United States Code, to Authorize the Designation and Assignment of Retired Justices of the Supreme Court to Particular Cases in Which an Active Justice Is Recused, GovTrack, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/s3871 [https://perma.cc/7QWN-MHWC] (last visited Aug. 11, 2020).

See, e.g., Steven Lubet, Disqualifications of Supreme Court Justices: The Certiorari Conundrum, 80 Minn. L. Rev. 657, 673, 675 (1996) (“Some of these objections could be answered by utilizing the services of retired Supreme Court Justices, where available.”).

28 U.S.C. § 371(b)(1) (“Any justice or judge of the United States appointed to hold office during good behavior may retain the office but retire from regular active service after attaining the age and meeting [certain] service requirements . . . .”).

McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 91.

Id.

28 U.S.C. § 294 (describing the nuances of the assignment of retired Justices or judges to active duty).

U.S. Const. art. III, § 1.

McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 107 (describing in detail the constitutional ramifications of Article III’s requirement as it affects designation).

See Reynolds & Young, supra note 9, at 39 (“Designation might well undermine the respect accorded even unpopular Supreme Court decisions.”).

Id.

See McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 96 (“In such circumstances, the more conservative Justices would presumably hesitate to call upon the services of a retired Justice who could swing the result in a liberal direction, and vice versa.”).

See id.

See Justices 1789 to Present, Sup. Ct. U.S., https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/members_text.aspx [https://perma.cc/H4V8-LGQY] (last visited Jul. 4, 2020) (describing the timeline of Justices on the Supreme Court and showing Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter as alive but no longer serving on the Court).

See McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 85 (describing how “before the 1990s, it was not unusual for a Justice to retire when no other retired Justice was living and competent”).

See, e.g., Reynolds & Young, supra note 9, at 35.

See supra Part IV.

See McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 112–13 (describing the possibility of “the appearance or reality” of bias with designation, depending on which Justice is chosen to replace a vacant seat, especially in instances where “a publicly engaged” Justice is chosen).

If all else fails, there’s always the tried-and-true, names-in-a-hat method!

See McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 101 (describing the drawbacks of a rotational system in a designation model of breaking ties, including that a Justice, who was on the schedule, “[e]ven if only unconsciously, . . . might choose not to recuse herself under a rotation system, in which she knew exactly which retired Justice was next in line to fill an empty seat”).

See generally The Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Senate Comm. on Judiciary, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/nominations/supreme-court [https://perma.cc/7BAT-7825] (last visited July 4, 2020) (describing briefly the process for appointing Justices).

See McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 101 (describing this in a designation scenario, where the Justice with the most experience would be brought on to fill the vacant seat).

See Washington v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 1832 (2018).

See An Act to establish the Judicial Courts of the United States, supra note 39.

See The Supreme Court Database, supra note 6 (showing that the last three-to-three equally divided vote in the Supreme Court was in 1987).

See, e.g., In re Isserman, 345 U.S. 286, 286, 290 (1953), rev’d on rehearing, 348 U.S. 1 (1954). In Isserman, the Supreme Court was originally tied, and on later rehearing, voted four-to-three with two Justices recusing themselves. Edward A. Hartnett, Ties in the Supreme Court of the United States, 44 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 643, 657 (2002). Here, we see the seven votes in action to resolve a tie.

See supra Part IV (describing the drawbacks of rehearings).

See McElroy & Dorf, supra note 14, at 102 (outlining the numerous questions that must be asked for implementing designation under the Leahy proposal).

See Rory Stott, Spotlight: Mies van der Rohe, ArchDaily (Mar. 27, 2020), https://www.archdaily.com/350573/happy-127th-birthday-mies-van-der-rohe [https://perma.cc/BK8P-TUTK] (crediting architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with the aphorism “less is more” as used in relation to his architectural designs).

See supra Part III.

See Rules of the Supreme Court of the United States, Sup. Ct. U.S. (Jul. 1, 2019), https://www.supremecourt.gov/ctrules/2019RulesoftheCourt.pdf [https://perma.cc/SLN6-YVF7] (providing no guidance about how the Supreme Court should deal with equally divided votes, recusals, or vacancies).

See supra Part IV.