I. Introduction

A long-standing belief within the science fiction community is that science fiction affects real-world innovation, and that it does so by illustrating technologies that are later created and adopted in the real world.[1] This thesis has particular resonance today. Many commentators posit that powerful tech moguls like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Mark Zuckerberg were influenced by science fiction, and that these stories motivated them to invent and invest heavily in advances in artificial intelligence, immortality, space flight, virtual reality, and more.[2] To quote Steve Bannon in an interview,

they’re all rushing — whether it’s artificial intelligence, regenerative robotics, quantum computing, advanced chip design, CRISPR, biotech, all of it . . . .

You know why? Because they’re complete atheistic 11-year-old boys that are kind of science fiction . . . guys . . . . Their business model is based upon that.[3]

The strongest proponent of the thesis that science fiction influences innovation was Hugo Gernsback.[4] Gernsback was a beloved science fiction editor and writer who founded the first exclusively-science-fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, in 1926, and the person for whom the “Hugo Awards” are named. Among science fiction enthusiasts, Gernsback has been praised as a pioneer in the field. He has even been called science fiction’s “father.”[5]

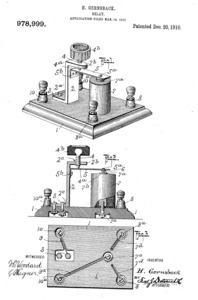

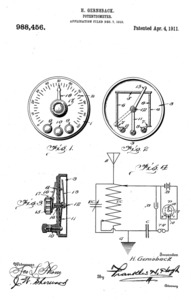

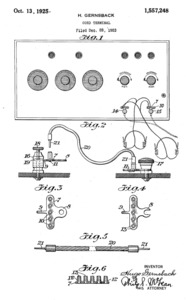

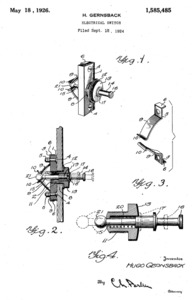

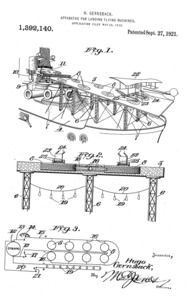

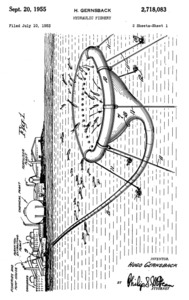

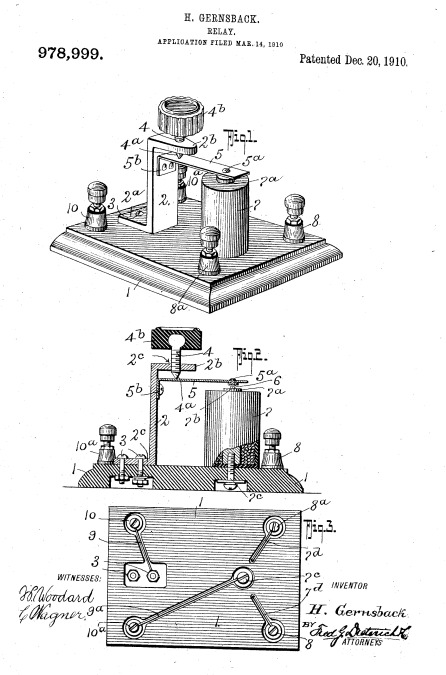

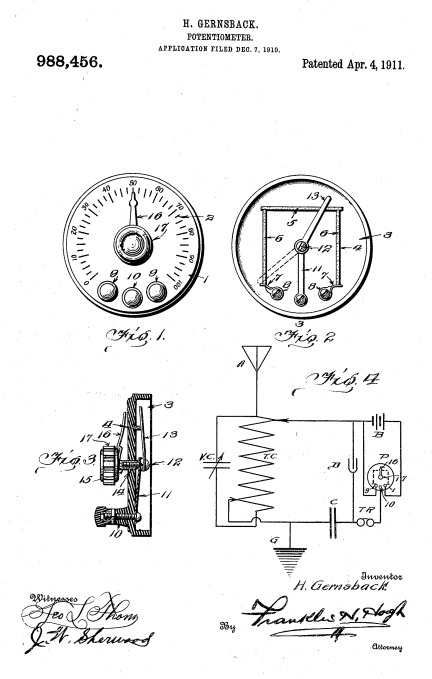

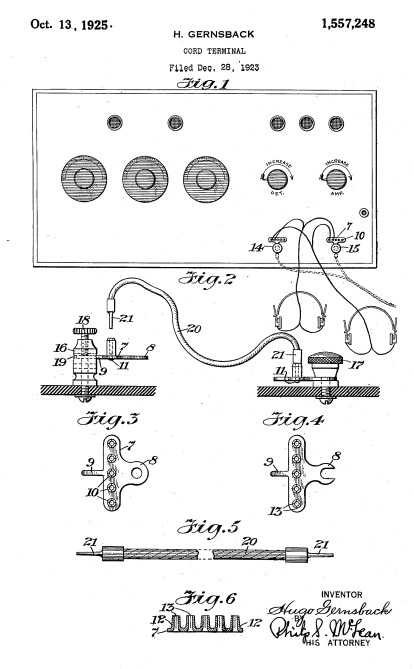

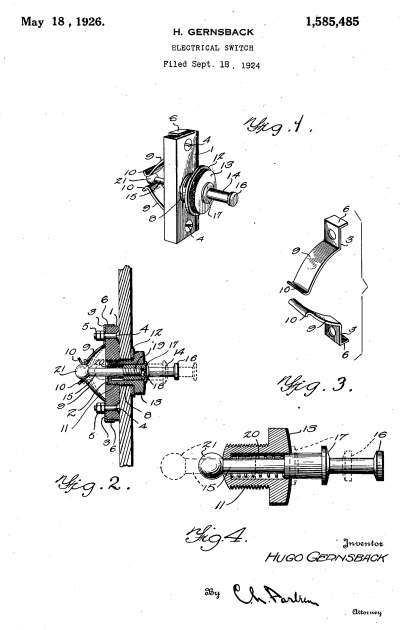

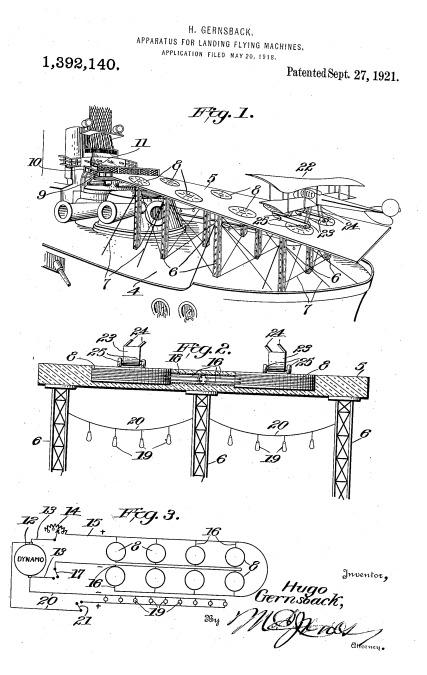

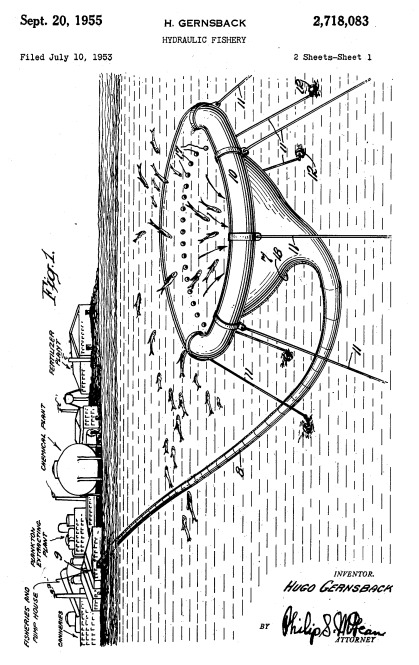

Too often overlooked is Gernsback’s legacy as an inventor and patentee. Gernsback was an inventor and entrepreneur in the budding fields of radio, wireless, and television; he started numerous electrical magazines marketed specifically towards inventors and would-be patentees.[6] Over his lifetime, Gernsback was awarded dozens of patents, many related to radio and telephone components,[7] such as the patents below:

Gernsback also obtained patents for more fanciful inventions, such as an “Apparatus for Landing Flying-Machines,” which used electromagnetism to facilitate landings where runways are short, such as on naval ships;[12] and a “Hydraulic Fishery,” which was basically a giant pumping mechanism that sucked fish through a tube, directly out of the water[13]:

In speeches and editorials that he wrote for his magazines, Gernsback argued that works of science fiction are similar to patents because they disclose useful information about future inventions, which future inventors could put into practice.[16] Gernsback was not the only proponent of this idea. Arthur C. Clarke, for instance, also believed that science fiction could “affect the future,” even going to far as to say that “by writing about space-flight we have brought its realisation nearer by decades.”[17] But Gernsback’s views on the mechanisms for how this occurs were unique. Gernsback explicitly drew the analogy between a work of science fiction and a patent.[18]

A “patent” is a document written by an inventor and published by the government.[19] Its purpose is to disclose an inventor’s new invention to the public in sufficient detail to allow others skilled in the technical field to make and use it.[20] In exchange for disclosing this information, the inventor gets an exclusive right to the invention for a set period of time—approximately twenty years—during which time only the inventor may profit from the use or sale of the invention.[21] Once the patent expires, the technical knowledge becomes free to anybody to use for eternity, providing new tools and building blocks upon which the cycle of innovation begins anew. This is called the “disclosure” function of a patent.[22]

Gernsback believed that works of science fiction operate in a very similar way. His observation was that science fiction stories can perform the same disclosure function by laying out scientific concepts and technical details for future inventions. Even if those inventions are not feasible on the day the story is published, professional scientists and inventors who read science fiction may one day be inspired to figure out how to complete—and likely patent—the inventions they learn about in science fiction. Thus, just as patents promote progress in science and technology by disclosing inventions and useful knowledge to the public, so too can science fiction.[23]

We call this the “Gernsback hypothesis.”

This Article shows how the patent record itself can be used to test the Gernsback hypothesis. We discuss various methodologies for searching the patent record to find links between science fiction and real-world patented inventions. We show that the patent record provides a wealth of data that can be used to support the claim that certain authors and works of science fiction have indeed played a role in the long chains of events resulting in the patenting of inventions. Crucially, though, the Article also lays out the significant challenges involved in using the patent record in this way. The patent record can reveal links between science fiction and innovation. For example, when a patent cites directly to a work of science fiction as prior art, or when a patent contains a unique word or phrase that was first used in a work of science fiction, we can assume that there was some connection between the prior work of science fiction and the ultimate patent.[24] But what this connection was is not always clear. The patent record is designed to omit almost the entire subjective back story of an invention, and so it inherently under-represents the influence of science fiction, telling only part of the story.[25] Still, it is an important part of the story, and one that is corroborated when juxtaposed with evidence outside the patent record.

II. Defining the Gernsback Hypothesis

The Gernsback hypothesis, as we use the term, refers to the theory that science fiction has the capacity to affect future invention and innovation by influencing inventors to put the invention, or a modified version of it, into practice. The Gernsback hypothesis, in other words, relates to science fiction’s “generative” potential, not merely its “predictive” potential.[26] In Gernsback’s view, a work of science fiction does more than accurately predict a future invention; it actually generates that invention by influencing someone else to put it into practice in the real world.[27]

We use the term “influence” here in a deliberately loose sense—consistent with Gernsback’s own fluid descriptions of science fiction’s generative effect on innovation.[28] Gernsback theorized that science fiction shapes future innovation by providing an “incentive,” a “stimulus,” or simply an “inspiration” to readers who later become inventors.[29] Gernsback’s theory was that the would-be inventor who reads (or, presumably, views) science fiction “absorbs the knowledge” contained therein “with the result that such stories” give the inventor “an incentive . . . to work on a device or invention suggested by” the science fiction author.[30] Even if the author did not know “how to build or make his invention” at the time she wrote the story, the subsequent “professional inventor or scientist . . . comes along, gets the stimulus from the story and promptly responds with the material invention.”[31] The science fiction author’s “brain-child . . . take[s] wings . . . when cold-blooded scientists” finally realize “the author’s ambition.”[32]

In drawing out this theory, Gernsback drew a direct comparison between a work of science fiction and a patent. He wrote that a science fiction story that discloses a new invention, and that inspires someone to make a functional version of that invention, is like a patent on a new invention that is sold to a manufacturer, who uses the patent to make an altered version of the invention “with but a few changes.” In both situations, Gernsback wrote, there is “progress,” even if no one realized beforehand in which direction it would lead.[33]

Gernsback felt so strongly that science fiction influences future inventions that he urged Congress to reform the Patent Act so that science fiction authors could obtain patents for their ideas. Gernsback proposed this idea in a speech he gave to the World Science Fiction Convention in 1952.[34] To briefly summarize the speech, Gernsback argued that it was unfair that science fiction authors were unable to patent and get credit for their inventions merely because they described them so long before they were patentable. He thought this was especially unjust because commercially minded readers might themselves go on to get patents for the inventions they read about in science fiction.[35] As a solution, Gernsback proposed two changes to the patent system. First, that a “Provisional Patent” be made available for science fiction authors, which they could later convert into a real patent if the invention became workable within a few decades. Second, that the patent office more regularly read science fiction in doing prior art searches.[36]

Gernsback’s proposal is thought-provoking. But, as we explain elsewhere, it is extremely problematic from the perspective of patent law policy.[37] If patents were available for aspirational, but not presently workable inventions, this would allow science fiction authors to use their patents to hold up future innovation, suing the people who eventually do the experiments to get the inventions to work. Imagine H.G. Wells and his estate being able to sue all physicists who study time theory because of Wells’s cursory descriptions of a time travel device in The Time Machine.[38] The public would get all the short-term burdens of the patent and none of the long-term benefits of useful knowledge.

Rather than ask whether science fiction authors deserve patent-style rewards, we focus here on exploring whether Gernsback’s premise was right. Now, a century after Gernsback founded Amazing Stories, we can test his hypothesis. We can examine whether science fiction actually functions akin to a patent, disclosing useful ideas and information that influences later inventors to advance the state of the art. And we can determine whether this science fiction–invention connection happens with any meaningful frequency.

III. Using the Patent Record to Test Gernsback’s Hypothesis

This Part will explain how the patent record itself can be used to test Gernsback’s hypothesis. To state the obvious, not all works of science fiction influence the future. Several conditions are necessary for the Gernsback hypothesis to be supported in a given instance. First, the author’s original work must have contained useful teachings related to science or technology. Second, those teachings must have been understood or internalized by some later inventor. And third, those teachings must have influenced that inventor’s conception of a later invention by providing a stimulus, incentive, or inspiration to make it work in the real world.

The patent record supplies an invaluable source of information for testing these conditions. All patents (and most patent applications) are published and are made easily searchable in public databases.[39] Thus, it should be possible to find references to science fiction in patents using these public databases.[40]

The ideal form of evidence would be to find a patent that cites directly to a work of science fiction and contains a verified statement from the inventor, such as, “I got the idea for this invention from X work of science fiction, which inspired me to go on and perfect the idea described in the story.” However, as we will see, this sort of evidence is almost never available. Patent law does not require inventors to reveal which sources influenced them and does not typically recount the details of how exactly an invention was conceived or how it evolved from conception to patent.[41]

In the following Sections, we explore various methodologies for using the patent record to test science fiction’s impact on innovation. We reveal several ways that this can be done. We identify the advantages, challenges, and limitations of each approach.

A. Chronological Approach

One way to try to prove the influence of science fiction on innovation is to simply identify inventions in works of science fiction that later appeared in the patent record. We call this the “chronological approach.” This approach is simple to employ. But it is not actually very useful for testing the Gernsback hypothesis. Priority on the timeline is not the same thing as influence.

1. Examples of the Chronological Approach

The chronological approach is quite common. Anyone with a passing skill at searching patents can easily find examples of patents that were presaged by similar inventions in science fiction. For example, a March 2015 issue of the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office’s newsletter for independent inventors proudly featured several well-known patented inventions that the author asserted “can be traced back to science fiction.”[42] For another example, the author notes that the automatic overhead door, which was described in H.G. Wells’s The Sleeper Wakes (1899), was later patented in 1967 and 1969. The author’s implication is that science fiction might have served as the “spark of inspiration” for these inventions.[43]

The chronological approach has also been adopted, in principle, by the remarkable website, Technovelgy.com. Technovelgy provides a crowd-sourced database of famous inventions, technology and ideas of science fiction writers that ended up having “similar real-life” analogues.[44] Technovelgy does not use the patent record and does not attempt to prove causation or a direction connection between work of science fiction and later invention. But with a bit of further research, it does yield many examples of science fiction inventions that ended up in the patent record.[45] Below, we discuss a few of these examples and provide side-by-side comparisons of the description in science fiction and a seemingly analogous patent. We will then go on to explain the strengths and limitations of this approach.

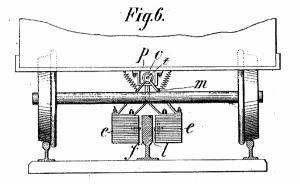

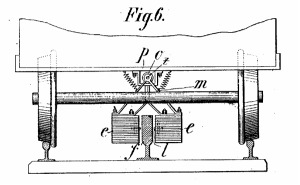

a. Magnetic Railroad. The first example we’ve selected is the magnetic railroad: a system of transportation that uses magnets to move trains along a track.[46] The theory (though not the practice) is simple: Use magnets on the train and/or track to leverage magnetic forces of attraction and repulsion to push and pull the train along. John Jacob Astor described this invention, in principle, in his fictional account of the world in the year 2000, published in 1894.[47] A magnetic railroad was patented as early as 1905.[48]

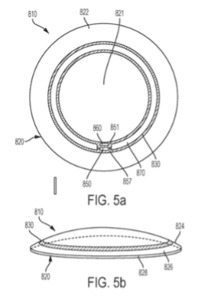

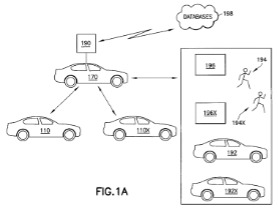

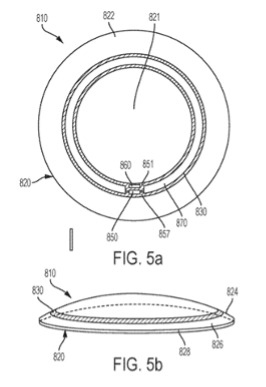

b. Smart Contact Lenses. The second example is a “smart” contact lens—a contact lens that is capable of overlaying information in the wearer’s field of view.[50] This has appeared in many works of science fiction, including a short story and a novel by Vernor Vinge, dating back as early as 2001.[51] A similar invention was patented as early as 2018.[52]

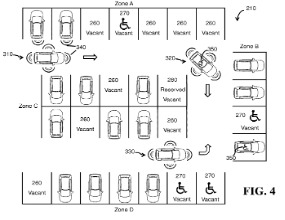

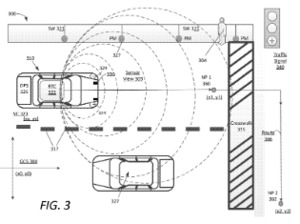

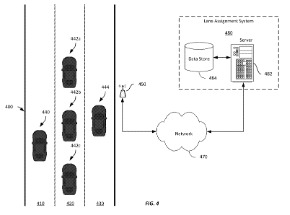

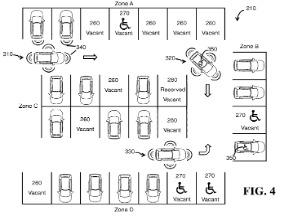

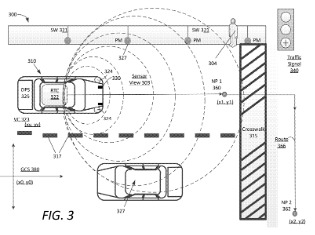

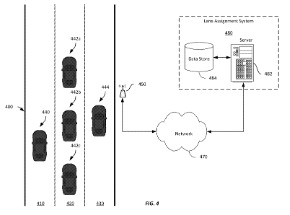

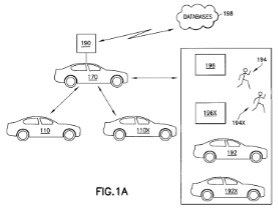

c. Self-Driving Automobiles. Our final example is self-driving automobiles. Self-driving automobiles have been a plot point in countless science fiction stories, such as Robert Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children (1941)[54] and Arthur C. Clarke’s Imperial Earth (1976).[55] Starting as early as the 2010s, autonomous vehicles have been put into use on public roads.[56] Several were developed by Waymo, Uber, and the electric car maker Tesla.[57] These innovations have been memorialized in many patents, filed not only by vehicle and sensor makers, but also by telecommunications and general computer hardware and software companies.[58]

2. Weaknesses of the Chronological Approach

We could go on and on with examples like those above. It seems highly unlikely that all such examples are purely coincidence and never indicate that the science fiction inspired the future invention. Others can certainly do more work in this area and correlate inventions in science fiction with later similar patented inventions. However, there are many limitations and weaknesses to this approach.

a. Chronological Priority Is Not the Same as Influence. First, the fact that a science fiction invention predates a patented invention tells us nothing about the influence of one on the other. While the prescience and inventiveness of these science fiction works are impressive—especially those that provide more detailed technical descriptions—this data alone cannot tell us whether the patentee was affected in any way by the earlier science fiction work. The inventor who obtained the patent may never have read a word the science fiction author wrote. They might have been “independent inventors,” reacting to the same trends in contemporary science and conceiving of their inventions independently of one another. In fact, many in the patent law community believe that independent invention is the norm.[65] For example, Astor’s description of magnetic railroads in 1894, and its subsequent patenting in the early 1900s, was probably an example of independent invention.[66] The entire span of the twentieth century contained a bona fide explosion of activity and experimentation with railroad technologies and electricity and magnetism (motors, generators, etc.).[67] Concepts surrounding electro-magnetic energy and levitation were “in the air,” so to speak, so we should not give undue credit to Astor’s 1894 fictional vision as influencing later patents. For sure, the fact that the science fiction author successfully anticipated many future patents is impressive. But this is predictive, not generative, and so not a true example of the Gernsback hypothesis as we define it above.

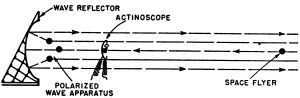

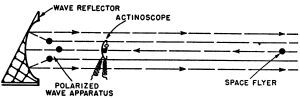

Ironically, an excellent illustration of this weakness is Gernsback’s own favorite example of science fiction’s importance to innovation—the case of radar. Gernsback frequently claimed that he accurately described the invention that would eventually be called “radar” in one of his Ralph 124C 41+ stories, first published in 1911.[68] The protagonist of Gernsback’s 1911 story was a genius from the year 2660 who used a “pulsating polarized ether wave” to pursue a Martian in his “space flyer” and to determine the speed and location of the Martian’s vehicle in space. Gernsback indeed seems to have described a real-world working version of radar—at least a very simple, high-level version of it. He provided a substantial technical description of the invention, and even included an image, shown below.[69]

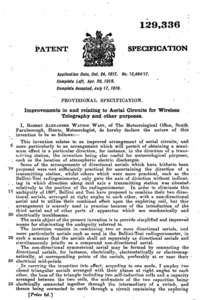

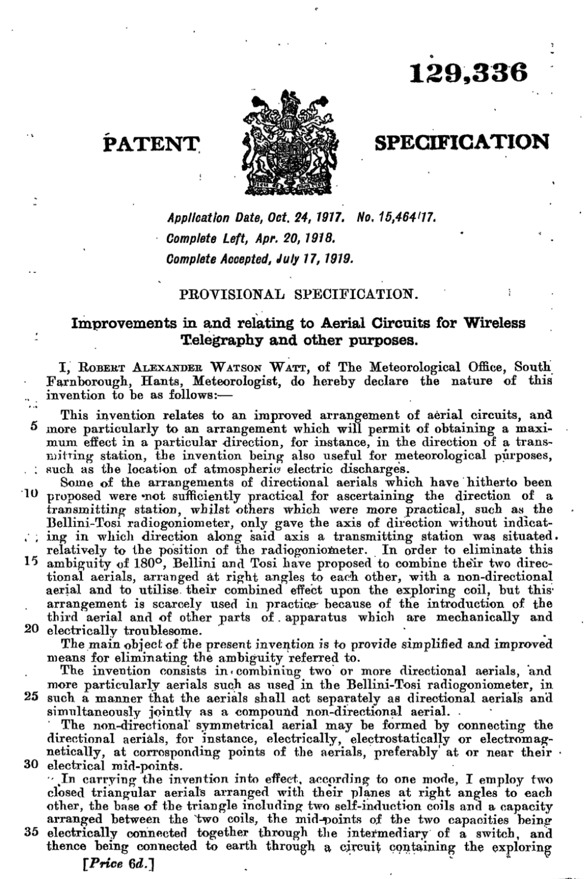

A few years later, in 1917, the British inventor Robert Watson-Watt filed for his first of several patents, laying the groundwork for radar technology.[71] The first page of his earliest patent specification is shown below. Radar was widely adopted by militaries in the 1930s.[72]

Gernsback received praise for his early description of radar. For example, Lee de Forest—a prolific inventor of radio technologies who was famous for inventing the vacuum tube that launched the consumer electronics industry[74]—wrote in a later letter to Gernsback that “[y]our fanciful suggestion as far back as 1911 should certainly have suggested to a later investigator of ultra-high frequency radio beams the possibility of using that principle as radar has now been used, for the detection of hostile airplanes.”[75] In the foreword to the second edition of Ralph 124C 41+, de Forest called it an “astonishing Book of Prophecy” and gushed over Gernsback’s remarkably accurate description of “the basic idea of radar as we know it today.”[76]

Despite such praise, Gernsback’s radar feat is complicated by two key facts. First, Gernsback did not really have priority, even for the “basic idea.” Others were thinking about these concepts long before Gernsback, and even before Watson-Watt. In 1905 and 1906, for example, renowned German inventor Christian Hülsmeyer received German Patent Nos. DE 165,546 and 169,154, which described his “Telemobiloscope”—a proto-radar device that used reflected electrical waves to detect the direction and distance of large metallic objects such as ships and trains.[77] Many still bicker over who is really the true, first “father of radar.”[78]

Second, there is solid proof that Robert Watson-Watt was completely unaware of Gernsback’s story when he made his inventions. When Watson-Watt was shown Gernsback’s earlier descriptions of radar, he “was astonished and thereafter maintained that Gernsback was the real inventor.”[79] Even Lee de Forest, despite his obvious admiration for Gernsback’s prescience, was under no illusion that the story itself had influenced modern advances in radar technology. In the 1944 letter mentioned above, de Forest went on to write to Gernsback that “[t]he chances are, however, that no investigator of VHF radiations in the 1930’s had ever read what you wrote in 1911. You may, however, take justifiable pride in the far-sightedness of many of your startling suggestions.”[80] Bummer. While this does not make Gernsback’s prediction any less remarkable, it confirms that the radar example provides poor support for the Gernsback hypothesis because a condition was missing—that Gernsback’s fiction actually be read. And his was not. Today, he is far better known as an editor and publisher than as an author.[81]

b. Mismatch Between Invention in Science Fiction and Invention That Is Ultimately Patented. A second complicating factor is that there is highly likely to be a serious mismatch between the inventions proposed in science fiction and inventions that are later patented. This could lead to underestimating science fiction’s influence. The chronological approach simply looks at whether a work of science fiction predated a patented invention. This works well in situations where the science fiction author coined a name for their invention or used some identifying terminology that helps prove the origin. Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash is a good example. Stephenson is credited as having coined the term “Metaverse.”[82] And that exact term does not begin to appear in the patent record until after the book’s publication in 1992. For example, a New York University patent filed in 1997, entitled “Method and System for Scripting Interactive Animated Actors,” explicitly refers to the “Metaverse” in explaining the motivation for a digital avatar-related invention.[83]

However, without clear references to unique terms (e.g., “Metaverse,” “Three Laws of Robotics”), it can be hard, if not impossible, to perform this tracing. This is especially true in light of the fact that the invention that is ultimately patented is likely to be very different from the invention that the science fiction author first proposed. Inventions go through multiple stages on the path from mere idea to patented invention.[84] The evolution from theory to practice is rarely straightforward.

Considering Stephenson’s “Metaverse” again, the NYU patent cites to his novel, removing all doubt that the science fiction teachings were considered by the inventors to be relevant. But the patent itself states its goal as providing useful technical tools that Stephenson did not disclose or describe, in order to enhance the capabilities of the virtual environment.[85] Had the inventors not included the explicit reference to Snow Crash, it would be very hard to find any link from the patent back to the science fiction that so inspired the inventors’ efforts.

For all these reasons, tracing the lineage of a real-world invention all the way back to its science fiction origins would be extremely difficult using only a chronological approach. Doing so is likely to overcount, or undercount, science fiction’s influence on innovation and is unlikely to shed enough light on the relationship between the two to draw firm conclusions about any “Gernsbackian” influence on innovation. To tackle this problem, the next Sections discuss how to use more detailed evidence from the patent record to draw more direct connections between works of science fiction and later inventions.

B. Formal Prior Art Citations

A potentially fruitful methodology for testing science fiction’s influence on innovation is to look for references to works of science fiction within the patents themselves.

By law, patents are only granted for inventions that are new and nonobvious as compared to the “prior art.”[86] The “prior art” includes, among other things, “printed publication[s]” and other sources that are sufficiently “available to the public.”[87] Works of science fiction are part of the prior art, just like any other printed publication.[88] Therefore, if it is true that science fiction inspired someone to make or perfect an invention that they learned about from a work of science fiction, the work of science fiction should, in theory, appear in the patent record as prior art.

Every application for a patent must undergo a thorough examination to ensure the invention satisfies all the criteria for patentability.[89] The most frequent points of contention are whether the invention is new and nonobvious as compared to the prior art.[90] The prior art cited in this context is often simply a prior patent, but it can also be a printed publication like a book, a website, or even a television show. It can even be a work of science fiction.[91] Applicants must cite any prior art known to be “material” to the patentability of their inventions.[92] Examiners, too, will cite prior art in the course of evaluating the patent. In fact, examiners usually rely on prior art that they find themselves, rather than trusting only the applicant’s citations.[93] If a patent is issued, the references cited during examination generally appear on the face of the final issued patent, which is searchable in public databases.[94]

In theory, then, searching the patent record should reveal instances where either patent applicants or patent examiners cited science fiction as formal prior art. A major stumbling block in applying this approach, however, is that, until the year 2000, patent applications that were filed but rejected were not made public.[95] This is unfortunate because it means we cannot find all the instances where the patent office rejected patent applications for inventions that had already been described in works of science fiction. Nonetheless, we have located some instances where science fiction has formally been cited as prior art against a patent application.

An example for which we have a decent paper trail is the inventor Charles Hall’s attempt to patent a waterbed. Hall applied for a patent for a waterbed, but the examiner initially rejected the application by citing to Robert Heinlein’s disclosure of a “hydraulic bed” in Stranger in a Strange Land (1961).[96] Heinlein’s details are sparse, but the core idea is there. “The patient floated in the flexible skin of the hydraulic bed,” Heinlein wrote, and he later described the bed as being fillable to set the amount of pressure and support to be provided by the flexible skin of the bed.[97] The patent examiner concluded that Heinlein’s hydraulic bed rendered the Hall invention not novel, or at least obvious, and thus not patentable.[98] Hall was eventually able to get a patent on his waterbed, but only by adding additional technical details to his application in a revised filing (called a continuation-in-part). This allowed Hall to sufficiently differentiate his invention from Heinlein’s disclosures.[99]

Another context in which science fiction has been cited as prior art is during patent litigation.[100] When someone is sued for patent infringement, a common defense is to argue that the patent is invalid because it was anticipated (rendered nonnovel) by prior art that the examiner did not consider.[101] Put differently, defendants get a second bite at the apple. They can find prior art that the patent examiner did not. During the so-called “smartphone wars”—patent litigation between Apple and Samsung in the 2010s—Samsung cited, among other prior art, Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece film 2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by Kubrick and co-written by famed science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke.[102] According to Samsung, one of Apple’s patents on the design of the iPad was invalid because it was essentially identical to the tablets used by the astronauts in the film, and therefore nonnovel or obvious.[103]

Given the enormous body of science fiction stories and the genre’s ever-increasing ubiquity in popular culture, one might expect that these kinds of prior art citations happen all the time. However, the reality is that science fiction is rarely cited as prior art. There are many reasons for this.

1. Science Fiction Disclosures Are Rarely Enabled

First, prior art references generally need to be “enabling.” In order for a reference to be cited to prove that an invention is not novel, the reference must disclose and “enable” all elements of the invention claimed in the patent application.[104] This does not mean the author of the prior art reference must have been able to practice the invention from reviewing the prior art reference. But it does require that a “person having ordinary skill in the art” could, in theory, make the invention after reviewing the prior art reference.[105] The majority of science fiction is unlikely to contain enough details to meet the enablement standard. Indeed, science fiction is likely to trigger both enablement and utility rejections.[106]

That said, the enablement requirement does not prevent all works of science fiction from entering the prior art. “Obviousness” rejections can be based on prior art that does not, on its own, enable all the elements of the claimed invention. Instead, the record must establish that a person of ordinary skill in the art could have made the claimed invention based on the references’ combined teachings and any other skills and knowledge that a hypothetical person in the art would possess.[107] What this means for our purposes is that a single mention of a technology in a work of science fiction, even if it is not itself enabled, could potentially be cited as prior art, so long as combining the science fiction with other references, and the state of the art as a whole, produces an enabling disclosure.

2. Science Fiction Might Not Be “Analogous”

Almost immediately, we run into another stumbling block. In order for science fiction to be cited as a reference for obviousness purposes, the prior art must additionally be deemed “analogous” to the patented invention—meaning it must either be from the “same field of endeavor” as the claimed invention or “reasonably pertinent” to the particular problem faced by the inventor.[108] Science fiction, to the extent it is considered a medium of entertainment, might not be deemed sufficiently “analogous.” Gernsback, for his part, did not see it this way. He thought science fiction should be considered as prior art and taken seriously by the patent office.[109] The fact that the patent office has occasionally referenced science fiction suggests that it can be deemed “analogous” and that at least some science fiction does indeed contain serious scientific principles that are likely to be read by inventors and by patent law’s hypothetical person having ordinary skill in the art. But there is no formalized policy on this point, and so it falls to the individual patent examiners’ and inventors’ discretion whether they conclude a work of science fiction is sufficiently analogous to cite.

3. Insufficient Incentives to Cite Science Fiction as Prior Art

The other major limitation is that, even if science fiction passes these legal hurdles and qualifies as prior art, it is not clear that anyone has the appropriate incentives to find it and cite it.

Patentees, to state the obvious, do not have natural incentives to cite prior art that would prevent them from getting a patent. As noted above, patent applicants (and their attorneys) must disclose any prior art known to be “material” to the patentability of the invention. Knowingly failing to disclose “material” prior art constitutes inequitable conduct that will render the patent unenforceable.[110]

At first glance, this might suggest that science fiction that directly inspired an inventor would have to be disclosed. However, patentees are not required to inform the patent office that a particular piece of prior art was “inspirational” to them or that it “influenced” their invention. Rather, information is only deemed “material” if “[i]t establishes, by itself or in combination with other information, a prima facie case of unpatentability of a claim” and it “is not cumulative to information already of record or being made of record in the application.”[111] A particular work of science fiction could certainly be both invalidating and not duplicative of other prior art. But in most cases, there will be other sources that include more technical details about the invention than the work of science fiction does. For example, an inventor does not need to cite to an Asimov story about robotics if they, or the patent examiner, have already cited to patents or science journal articles that disclose essentially the same content. This is the case even if the Asimov story was far more influential and inspirational to the inventor’s thought process and career than the journal article.

Examiners, meanwhile, have similar incentives not to dwell on science fiction. It is, of course, possible for patent examiners themselves to raise science fiction as prior art, as occurred in the Robert Heinlein example.[112] In fact, research suggests that examiners usually rely on references they find themselves.[113] However, the reality is that examiners are unlikely to have the resources to do an exhaustive search. The backlog of patent applications is years long, and examiners spend a remarkably small amount of time on each application to help keep the trains moving. It is estimated that they spend about eighteen hours total per application.[114] Examiners are looking to find the best, most closely analogous prior art reference to cite, and in the most efficient way possible. That effort is likely to be much more fruitful when focused on nonfictional, technical patents and journal articles. Not only is the science typically far more detailed, but these sources are better catalogued and more easily searchable. References buried within works of science fiction are much harder to locate. Examiners under this kind of time pressure are unlikely to spend much time reading through science fiction references in the hope of finding a relevant technical disclosure (not on the clock, at least).

For all these reasons, formal citations to science fiction are likely to be rare. Relying only on formal prior art citations to test science fiction’s impact on innovation would be a grossly underinclusive measurement. If one tallied up the science fiction citations versus patent and journal citations, one might be left with the impression that science fiction has virtually zero impact on real-world invention. But this would be the wrong conclusion to draw because the patent system’s rules are set up to disfavor citing to science fiction, regardless of how much influence on inventors it actually has. The waterbed and iPad examples are interesting, but they are the exceptions that prove the rule. Even when considering obviousness, examiners are just not very likely to receive science fiction from inventors, and they are even less likely to go out and find it themselves.

C. Informal References to Science Fiction in Patents

Fortunately, the patent record supplies significant information beyond formalized citations to prior art. Science fiction can appear in patents in more informal ways as well. Patents sometimes mention science fiction authors, their ideas, or specific works in the body of the patent—not as a formal prior art citation.[115] This means the patent applicant or their attorney themselves added the reference. Although such references are rare in comparison to references to traditional scientific sources, they do appear. As discussed below, a review of some of these informal references strongly suggests that the inventor was influenced in some way by the cited author or work of science fiction. That said, as we will show, the measure of that influence is highly context specific. Some references indicate barely any influence, while others suggest a strong influence.

1. Jules Verne

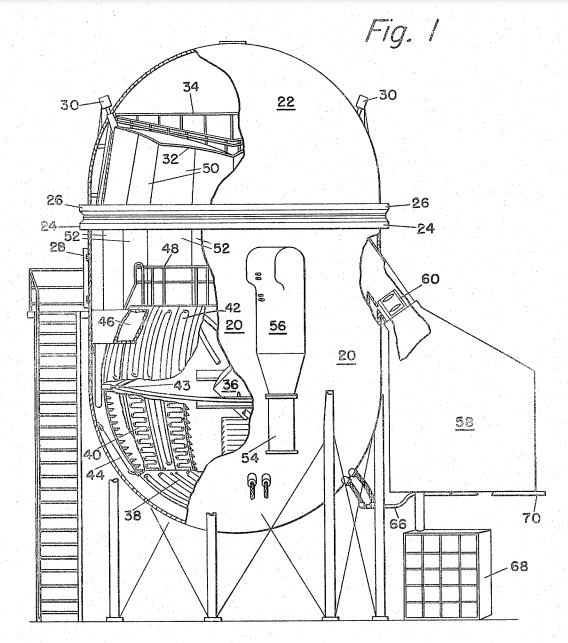

An obvious place to start is Jules Verne. Verne is known for his credible inventions and reliance on real technical details.[116] Perhaps not surprisingly, then, Verne appears frequently in the patent record. For example, a 2020 rocket-related patent lists Verne’s moon cannon in From the Earth to the Moon before any other prior art, as if to suggest that it is the closest analogue to the claimed invention, despite its shortcomings.[117] In another patent application for a sled- and rail-based launching mechanism, Verne’s ideas are described alongside and equal to other “real-world” prior art.[118] Perhaps the greatest reverence for Verne comes in a patent owned by General Electric (GE), directed to a simulator environment for testing equipment used in space:

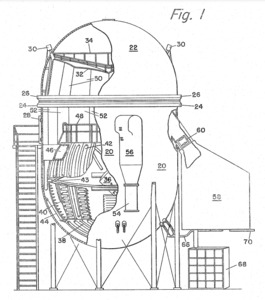

The patent begins by emphasizing the importance of testing under simulated conditions and goes on to praise Verne’s work for its “extremely plausible” science and its helpful imagining of problems that can arise in space. GE treats Verne’s 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon, in which Verne proposed a cannon to launch people to the moon, as equivalent to a scientific hypothesis or thought experiment.[120] This patent’s discussion of Verne’s moon cannon reveals more than just high-level inspiration. It suggests that GE even relied on some of Verne’s technical details, even if it was in part to critique or improve upon them.[121]

2. Isaac Asimov

Another major figure who appears is Isaac Asimov. A search of Google Patents found Isaac Asimov’s name seventy-five times in the patent record.[122] This is never as an inventor himself but usually in connection with the computer-related inventions of others. Many of these references use Asimov’s name in the course of explaining what the invention is and how it might work.[123] For example, Asimov’s work was cited to help explain the term “cyborg,”[124] to support the viability of ionic propulsion for spacecraft,[125] to suggest the need for fungal and other micro-organism-based food sources,[126] and as context for the potential of micro-surgical tools.[127]

Sometimes the mentions are less substantive and more incidental. A Google-owned patent cited to Asimov when explaining a web-searching invention, for example. The patent mentioned “Isaac Asimov” and his book “The Robots of Dawn” as an example of a data relationship that might be triggered using the invention’s methodology, but the invention did not relate to any particular aspect of the Asimov novel.[128] Google could have chosen any author/book combination, but it chose this, ostensibly as a subtle “nod” or “wink” to Asimov.

One of the most common reasons that patents reference Asimov is to invoke his famous “Three Laws of Robotics” (Three Laws). During the 1940s and '50s, Asimov published many stories and novels in which he posited that robots might be created to work cooperatively alongside humans and be programmed to follow three laws:[129]

-

Do not injure a human through action or inaction.

-

Obey orders from a human except if in conflict with First Law.

-

Protect own existence except if in conflict with First Law or Second Law.[130]

In the patent record, the Three Laws are mentioned dozens of times in descriptions of inventions relating to robotics and artificial intelligence.[131] For the most part, these are legitimate citations. Even if in some cases patents mention the weaknesses or naivete of the Three Laws,[132] most of these references reveal inventors taking Asimov’s discussion of the Three Laws quite seriously. For example, a 2021 patent entitled “System and Method for Conscious Machines” notes that Asimov accurately “anticipated” the challenges involved in creating thinking machines when he posited his Three Rules.[133]

Other references to Asimov are less explanatory and more in the nature of paying homage. For example, one inventor explains in his patent that he has decided to change the shorthand name of the invention from Self Organizing Data Base, used in earlier patent applications, to “AC,” “because it pays tribute to Isaac Asimov, who told the tale of AC, a computer that answered every question (in the story The Last Question).”[134] At the least, these sorts of references imply that Asimov played a part in motivating the research, if not the career paths, of the inventors. At a minimum, they would suggest that, at some point in time, Asimov’s stories or ideas captured their attention and perhaps triggered their imagination in the way Gernsback theorized.

3. Why Informal References Matter

There are many more examples we could cite, but none of a fundamentally different character from those described above. Search Google Patents for “Star Trek” and you will have over 3,000 patent documents to explore.[135] Name a tech giant—Microsoft, Apple, IBM, Sony, Adobe, eBay, TiVo, Intel, Facebook, LinkedIn, Comcast, DirecTV, Verizon, AT&T, Google—and you will see they have found ways to mention the trailblazing Star Trek franchise somewhere in one of their patents.[136]

We consider these informal mentions to be, in many cases, highly indicative of science fiction’s influence on these particular patents. Many of these informal references reveal that inventors take the disclosures of at least some science fiction seriously. The fact that these references made it into the patent record despite all the legal and practical obstacles makes them even more significant. Some of these references, on their face, reveal that the inventor saw the science fiction as supplying guidance on what to do, or what not to do. At minimum, these references reveal an homage or “tip of the hat” to science fiction that suggests some level of influence. Even if the final invention that is described in the patent looks very, very different from its forebearer in science fiction, the fact that the forebearer is referenced at all may be evidence that it affected the inventor in at least some small way along the lines that Gernsback described.

That said, it is important to concede that a mere mention in a patent does not necessarily indicate the reference had influence on the inventor. For example, the fact that a patent mentions Asimov’s Three Laws does not confirm that Asimov’s ideas were a part of the chain of events that led this inventor to their specific invention. The allusion to Asimov could have been an afterthought or an artistic embellishment. The inventor might not have been responsible for the reference at all! Patents are, for the most part, drafted by attorneys, not inventors (though inventors must, in all cases, formally approve the applications).[137] It is at least possible that some of these informal references were included to make patents more engaging and relatable—not to indicate anything particular about the origin of the invention. As one patent attorney discusses, alluding to an element of science fiction in a patent can help by more “deeply illustrating the concept than a few, uninspired paragraphs (lacking such a reference) might otherwise achieve.”[138] For example, when writing a patent relating to “virtual meetings that use ‘a photo-realistic 3D experience of the meeting’” it can be a benefit to everyone—applicant, examiner, and readers alike—to analogize this to “a Star Wars®-type hologram experience.”[139]

As discussed below, a way to deal with these questions is to seek other evidence from outside the patent record to confirm science fiction’s influence.

D. External Evidence

A final approach for testing the Gernsback hypothesis looks beyond what is found in the text of the patent record, branching out to external sources. For example, by looking at speeches, media quotes, or interviews with inventors, we can bolster the supposition that an inventor relied on or was inspired by a work of science fiction in a way that meaningfully—and technically—contributed to the invention they ultimately patented. The key for these examples is to locate external evidence proving that a specific author or work of science fiction inspired the inventor to go out and perfect the author’s invention, resulting in a finalized patent.

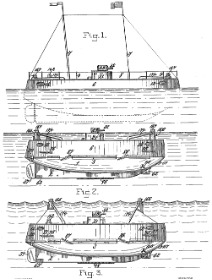

One of the best-known examples of this type is the tale of how Jules Verne inspired Simon Lake, an American engineer and naval architect, to invent the modern submarine.[140] Lake was a huge fan of Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and described Jules Verne as “the director-general of my life,” responsible for guiding his career trajectory into naval engineering. Lake gushes about Verne in his autobiography, describing how he was inspired by Verne’s description of the “Nautilus” and became obsessed with making and improving upon it.[141] In Lake’s own words,

Jules Verne was in a sense the director-general of my life. . . . I read his Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea and my young imagination was fired. . . . [W]ith the impudence . . . of the totally inexperienced I found fault with some features of Jules Verne’s Nautilus and set about improving on them.[142]

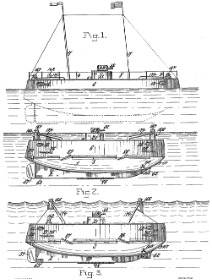

Lake’s obsession paid off. About thirty years after the novel was published, Lake was awarded a patent that looks and works very much like the Nautilus is described, even including how water tanks could be filled or emptied as needed to change the buoyancy for diving and surfacing.[143] When Lake completed construction of his much-anticipated submarine, the Argonaut, he received a congratulatory telegram from none other than Verne himself.[144]

The Lake patent is shown below alongside its science fictional source.

There are more examples like this, several of which also involve Verne—a testament to his influence on many readers. We have identified more of them in detail elsewhere.[147] Our point here is to explore this methodology, which could be used to locate and analyze more examples.

External evidence from inventors themselves, in the form of writings, speeches, and of course interviews, arguably provides the most direct evidence of whether a work of science fiction influenced the development of a patented invention. If the inventor listed on the patent attests directly that science fiction inspired and encouraged him to make and improve upon an invention that he saw described in science fiction, this is the best evidence that is likely to be available. We can’t perform a Vulcan mind meld. But we can see or listen to what the inventor wrote or said in her own words.

Yet there are some limitations with this approach, too. The first limitation is that this kind of evidence is simply unavailable for less famous inventors or less consequential inventions. The hundreds of thousands of run-of-the-mill improvement patents awarded every year to armies of engineers and researchers will never have the kind of notoriety to be the subject of magazine articles or commencement speeches. We just do not have this type of invention-story data about the overwhelming majority of inventions.

The second limitation is that, in most conceivable cases, even lock-tight evidence of influence does not indicate the degree of that influence. As discussed above, the path from mere idea to innovation-as-practiced is often a winding one. The ideas as initially proposed “on paper” very rarely look like the completed version that ends up in the patent record, let alone in the marketplace.

Consider the case of Robert Goddard. Goddard was an American physicist widely regarded as a space-flight pioneer.[148] In 1914, Goddard obtained two patents for combustion-propelled rockets.[149] As we have discussed elsewhere, Goddard was at least indirectly inspired by the Jules Verne book, From the Earth to the Moon, where a manned projectile made the trip after being fired from a giant cannon.[150]

However, when we look at this example more closely, it is not clear how much real influence Verne had on Goddard. Their inventions were ultimately quite different. To be sure, the challenge Goddard attempted to overcome was the very same as Verne’s, and at a high level, the two men’s solutions shared some similarities. Both relied on the explosive force of chemical combustion to propel an object into space. But whereas Verne used a giant cannon to fire a manned capsule to the Moon,[151] Goddard’s design essentially went about it from the other direction. Goddard found it more efficient to effectively turn the cannon around and point it down instead of up, propelling the cannon (rocket) upward with a slow, continuous explosion instead of one big bang.[152] Even the popular press at the time could understand the difference. As Goddard geared up to test one of his missile designs, the New York Times reported that Goddard and Verne worked “along distinctly different lines”; “[w]here Verne thought of a cannon a half mile long[,] . . . Dr. Goddard has surpassed Verne by doing away with the troublesome cannon of half-mile barrels.”[153]

Does this mean Verne had no influence on Goddard? Not at all. But it does illustrate that even the best evidence of influence does not tell us how much impact the science fiction author’s ideas really had on the ultimate technology that proved to be practicable.

Another example of this limitation is actually Verne’s influence on Simon Lake. It is hard to deny that Verne, whom Lake called the “director-general” of his life, had influence on Lake as a general matter (pun intended).[154] And there is undeniably significant similarity between Lake’s submarine and its fictional forebearer, Verne’s Nautilus. As shown in Table 4 above, Verne depicted a submarine that dives and resurfaces in a very specific way, and Simon Lake’s patent discussed the functionality in very similar terms. True, Lake’s patent went into much further detail (e.g., particular combinations of cranks, shafts, and pistons) and added optional features (e.g., an escape buoy) that were absent from Verne’s story. But the patent Lake obtained was awarded, in large part, for the enablement of core concepts that had appeared in Verne’s writing.[155]

However, even in this case, Verne did not himself invent the first submarine, or even the first “Nautilus.” Verne was not the first to describe an underwater vehicle. In fact, another “Nautilus” had been tested several decades before Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea was serialized starting in 1869.[156] In the 1790s, Napoleon, then Emperor of France, commissioned a submarine from the famous American inventor, Robert Fulton, who chose the name “Nautilus.” The submarine was tested in the year 1800 but was never widely used (it leaked). Napoleon abandoned the project.[157] Again, does this mean Verne had no influence on Lake? No. Lake himself attests that he was inspired by Verne’s description (and presumably not by Robert Fulton’s leaky prototype).[158] And yet, it is hard to say that Verne was “responsible” for Lake’s submarine—effectively nullifying all of Lake’s own hard-earned knowledge, training, and intellect. If Verne had never existed, it is very likely someone, perhaps Lake himself, would have invented a submarine that looked more or less like Verne’s, and perhaps even would have called it the “Nautilus.”

The final limitation is the ever-present risk of “hindsight bias.” Even if we went door-to-door to interview every inventor about the motivations behind their inventions, and even if the overlap between their inventions and a supposedly motivating work of science fiction was very high, we would still have to contend with the deceptive lens of hindsight. It is easy to say after the fact that you were influenced by, for example, Star Trek, but at the time, was this so? People often give post hoc rationales for what they did when, in reality, other thoughts and motivations were at work. It is a human tendency to impose a logical narrative when pressed to explain our actions, and sometimes dots are connected that should not be.

We see this bias at work in a famous real-world example. The story goes that Martin Cooper, who is praised for having invented and patented the first cell phone, was directly inspired by the communicator device from Star Trek: The Original Series.[159] As first described in the Original Series, the communicator is a compact handheld device with a hinged, closable cover over its buttons and speaker/microphone.[160] As reported in Forbes magazine, the legend goes that “Martin Cooper can recall the moment when he was at a break in his lab watching the episode of Star Trek when Kirk used his Communicator to call for help for an injured Spock, which later inspired him to invent the mobile phone.”[161] Cooper ultimately obtained a U.S. patent on the idea of portable units communicating via base stations in 1975.[162]

But this story has been disputed by Cooper himself. Cooper gave an interview in 2015 stating that the story about watching Star Trek while inventing the cell phone was exaggerated. He was, in fact, inspired by technology from prior to Star Trek, such as Dick Tracy’s wrist-worn communicator.[163] It seems Cooper got a bit carried away. In the interview, he admitted that, once the story started going around, he “conceded to something that he did not actually believe to be true.”[164] It is possible he was star-struck by William Shatner, the star of the original Star Trek series, who has argued, albeit without causal evidence, that Star Trek inspired much of the technology we have today.[165]

Addressing hindsight bias is an unavoidable challenge in the patent world. Once the solution to a problem is known, that solution seems natural, perhaps inevitable, and therefore obvious—i.e., unpatentable. Inventors and patent lawyers are in a Sisyphean struggle with patent examiners to ensure the examiners are refraining from using improper hindsight to reconstruct the invention from bits and pieces of prior art. The patent law, by statute, asks not whether it seems obvious now, but whether the invention “would have been obvious” to a skilled person in the field at the time, without knowing what the inventor’s solution would later be.[166] As the U.S. Supreme Court emphasized in KSR International Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., “[a] factfinder should be aware, of course, of the distortion caused by hindsight bias and must be cautious of arguments reliant upon ex post reasoning.”[167]

That sentiment is a good place to end, as it is an overarching reminder of the limitations of this journey through the patent record. A patent application comes only after an invention has been conceived, so the motivations and thought processes that brought forth the invention are always, in a sense, water under the bridge.

IV. Conclusion

Like witness marks on a clock, we can find clues in the patent record from which a plausible narrative of an invention might be constructed. Sometimes, we can make a strong case that a work of science fiction influenced the inventor. But, unlike a clockmaker, we will never hear the confirmatory “tick-tock” to show that we put the pieces together right. We cannot divine what really sparked the insights that rose to the level of patentable inventions. In a stricter interpretation of the Gernsback hypothesis, we do not see much evidence to show that science fiction discloses useful technical information that drives technical progress. Certainly no evidence that this occurs on a broad scale.

But nor do we throw up our hands and reduce all of the evidence to mere coincidence. What the patent record does reveal is that context matters, and not all stories look the same. When science fiction enters the public consciousness, it affects some inventors in profound ways. It can inspire inventors to enter science as a career. It can make them curious and excited about specific ideas they first saw in science fiction. Some of those inventions do result in patents. Some of those patents do refer back explicitly to their science fiction forebearers, either as formal prior art citations or as informal references.[168] When that occurs, the patent record is a fantastic and unmatched resource for tracing innovation back to its science fiction origins.

On the other hand, some inventors, probably the vast majority, are not influenced by science fiction at all. Even those who are do not typically reveal that influence in patents. In these situations, it is necessary to get more creative. A chronological approach—simply seeking science fictional descriptions that predated a patent—can be a good start. This works for inventions like the “Metaverse” that have a specially coined name. It can also potentially work for inventions that so closely resemble their science fiction antecedents that influence seems likely. This could be especially fruitful if combined with new tools from data science and increasingly powerful artificial intelligence, which could be used to correlate textual passages in science fiction with textual passages in patents. This approach does not work, however, for the vast majority of patents because they are unlikely to resemble their science fiction origin. Even if there was inspiration, the patented invention might add new features and concepts that the science fiction author never envisioned, or might move concertedly away from, and try to fix, problems that the inventor saw in science fiction.

All that said, the conclusion to take from this is that the fact that science fiction shows up in the patent record at all is alone testament to its influence. As we have explained, there are multiple barriers, legal and practical, to citing science fiction in patents. Science fiction rarely provides the “enabling” details patent law requires for a prior art reference to be considered. Even when it does, patent applicants are under no obligation to disclose science fiction that influenced them—and they have little incentive to do so given the risk of being preempted. Patent examiners, time pressed and working to dig out from under an enormous backlog of applications, are far more likely to seek out analogous patents and journal articles when doing prior art searches. Why take the time to track down and cite to a science fiction book if the same idea is discussed elsewhere in a more readily available nonfiction source?

Despite there being essentially no reason for it to do so, science fiction appears in the patent record. It was important enough to form some part, however small, of the journey that culminated in the invention. At the end of the day, there is really only one explanation for this: Some inventors read science fiction, and science fiction matters to those inventors. Its ideas inspire them and influence what they do in ways that more traditional sources—textbooks, journal articles, and, of course, patents—simply do not. Gernsback put it best. Science fiction discloses useful information, and it does so “in a very palatable form. . . . [I]mparting knowledge, and even inspiration, without once making us aware that we are being taught.”[169] Provided that the author “is a good story teller,” science fiction fires the reader’s imagination perhaps more than anything else of which we know, leaving readers “deeply thrilled,” as their “imagination is fired to the nth degree.”[170] Few people would ever say that about reading patents.

Leslie Lieber, Science on a Spree, This Wk. Mag., Apr. 26, 1947, at 4, 5.

See, e.g., Andrew Liptak, Tech CEOs Should Stop Using Sci-Fi as a Blueprint for Humanity’s Future in Space, Transfer Orbit (July 14, 2021), https://transfer-orbit.ghost.io/tech-ceos-should-stop-using-science-fiction-as-a-blueprint-for-humanitys-future-in-space/ [https://perma.cc/KPD7-TTYR] (“Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos have repeatedly highlighted how science fiction has influenced their worldviews.”); Christian Stadler, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos Were Inspired by Sci-Fi and So Should You, Forbes (May 4, 2023, at 13:42 ET), https://www.forbes.com/sites/christianstadler/2022/03/22/elon-musk-and-jeff-bezos-were-inspired-by-sci-fi-and-so-should-you [https://perma.cc/NV38-TQCH] (discussing science fiction’s influence on Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos); Anujj Trehaan, Favorite Sci-Fi Novels of Musk, Gates, Zuckerberg, and Bezos, NewsBytes (Mar. 12, 2024, at 13:41 CT), https://www.newsbytesapp.com/news/lifestyle/visionaries-top-sci-fi-novel-picks/story [https://perma.cc/M9JU-7SME]; see also Christian Davenport, The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos 38–42, 251, 254 (2018) (discussing billionaire entrepreneurs’ efforts to revitalize the U.S. space program and the rise of commercial space companies like Blue Origin, led by Bezos, and SpaceX, led by Musk).

Ross Douthat, Steve Bannon on ‘Broligarchs’ vs. Populism, N.Y. Times (Jan. 31, 2025), https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/31/opinion/steve-bannon-on-broligarchs-vs-populism.html [https://perma.cc/24MS-TMUR].

Camilla A. Hrdy & Daniel H. Brean, The Patent Law Origins of Science Fiction, 47 Colum. J.L. & Arts 1, 9–10, 19–20 (2024) (revealing that Hugo Gernsback believed that works of science fiction have an effect on technological innovation and are analogous to patents).

Hugo Gernsback: "Father of Science Fiction," reprinted in Sam Moskowitz, Explorers of the Infinite: Shapers of Science Fiction 225, 242 (Hyperion 1974) (1963).

Gary Westfahl, Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction 61 (2007). See generally Hugo Gernsback, The Perversity of Things: Hugo Gernsback on Media, Tinkering, and Scientifiction (Grant Wythoff ed., 2016) [hereinafter The Perversity of Things] (a collection of Gernsback’s writings on invention, wireless technology, and early science fiction).

Hugo Gernsback, The Detectorium, 8 Radio News 237 (1926), reprinted in The Perversity of Things, supra note 6, at 299, 302 (assessing Gernsback’s role in technological revolutions occurring in telephone and radio).

U.S. Patent No. 978,999.

U.S. Patent No. 988,456.

U.S. Patent No. 1,557,248.

U.S. Patent No. 1,585,485.

U.S. Patent No. 1,392,140 col. 1 ll. 9–12, 32–37, 42–44, col. 2. ll. 65–66.

U.S. Patent No. 2,718,083 col. 1 ll. 15–27.

'140 Patent.

'083 Patent.

Hrdy & Brean, supra note 4, at 19.

Neil McAleer, Arthur C. Clarke: The Authorized Biography 126 (1992).

Hrdy & Brean, supra note 4, at 20.

Patents, AIPLA, https://www.aipla.org/about/what-is-ip-law/patents [https://perma.cc/4DHY-C6Q6] (last visited Sep. 15, 2025).

See 35 U.S.C. § 112.

See id. § 154 (describing term of patent as twenty years); see also Daniel Brean & Ned Snow, Patent Law: Fundamentals of Doctrine and Policy 37 (2020) (explaining basics of patent law and doctrine).

Jeanne C. Fromer, Patent Disclosure, 94 Iowa L. Rev. 539, 545 n.18, 548 (2009).

See Hrdy & Brean, supra note 4, at 19–20.

See, e.g., infra notes 83–85, 118–20, 141–47 and accompanying text.

Patent law scholars have frequently observed that patent disclosures are not as useful as they could be, even with regard to their basic disclosure function. See, e.g., Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, Do Patents Disclose Useful Information?, 25 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 545, 553, 558 (2012) (empirically evaluating the degree to which inventors actually use patents as a source of technical information); Sean B. Seymore, Uninformative Patents, 55 Hou. L. Rev. 377, 387–88 (2017) (observing that patents need not disclose precisely how or why an invention works).

As Gary Westfahl puts it, Gernsback was adamant that science fiction plays a role “in not only predicting, but actually creating, the future.” Westfahl, supra note 6, at 19; see also Gary Westfahl, Pitfalls of Prophecy: Why Science Fiction So Often Fails to Predict the Future, in Science Fiction and the Prediction of the Future: Essays on Foresight and Fallacy 13–14 (Gary Westfahl, Wong Kin Yuen & Amy Kit-sze Chan eds., 2011) (describing the fallacy of analogy when expecting new technologies to be adopted as imagined in science fiction); Daniel M. Russell & Svetlana Yarosh, Can We Look to Science Fiction for Innovation in HCI?, Interactions, Mar.–Apr. 2018, at 36, 40 (distinguishing between science fiction as a predictor of future technologies and as a source of inspiration).

See sources cited supra note 26.

Hrdy & Brean, supra note 4, at 18–20.

Karen Myers, Roots of the SFF Genre: Hugo Gernsback, Patent Law, and Amazing Stories, Mad Genius Club (Feb. 2, 2023), https://madgeniusclub.com/2023/02/02/roots-of-the-sff-genre-hugo-gernsback-patent-law-and-amazing-stories/ [https://perma.cc/NA7K-U6LL].

Hugo Gernsback, The Lure of Scientifiction, 1 Amazing Stories 195, 195 (1926).

Hugo Gernsback, $300.00 Prize Contest: Wanted: A Symbol for “Scientifiction”, 3 Amazing Stories 5, 5 (1928).

Id.

Hugo Gernsback, Imagination and Reality, 1 Amazing Stories 579, 579 (1926).

Hugo Gernsback, The Impact of Science Fiction on World Progress 5–6 (Aug. 30, 1952) (unpublished manuscript) (on file with author) (Address Before the 10th World Science Fiction Convention).

Id. at 4 (“[F]ive, ten, or thirty years later someone who read [an author’s] original story will remember the idea, lard it with a few of his own, patent it and start a new billion dollar industry on it. . . . [T]his sort of thing happens continuously.”).

Id. at 5–6.

Hrdy & Brean, supra note 4, at 33.

H.G. Wells, The Time Machine 14, 16–19, 21, 23–24 (1895).

35 U.S.C. § 122.

The patent office supplies many databases and other resources for searching patents. See, e.g., Search for Patents, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/search [https://perma.cc/AYF6-3CZL] (last visited Sep. 6, 2025). Google Patents also provides searchable patent data. Google Pats., https://patents.google.com/ [https://perma.cc/W3UT-B43W] (last visited Sep. 6, 2025). We use Google Patents for our discussion because it is more intuitive and easier to use.

Applying for Patents, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/patents/basics/apply#utilityspec [https://perma.cc/QTK7-CPRV] (last visited Sep. 6, 2025) (providing a list of the information that must be contained in the specification of a nonprovisional utility patent application).

Messina Smith, Science Fiction to Science Fact, USPTO (Mar. 2015), https://web.archive.org/web/20210920143215/https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/newsletter/inventors-eye/science-fiction-science-fact# [https://perma.cc/Q7DX-QNKJ].

Id.

Home, Technovelgy.com, http://technovelgy.com/ [https://perma.cc/H8N7-3P6J] (last visited Sep. 6, 2025); Timeline of Science Fiction Ideas, Technology and Inventions, Technovelgy.com, http://technovelgy.com/ct/ctnlistPubDate.asp [https://perma.cc/DX9H-N6BS] (last visited Sep. 6, 2025).

See sources cited supra note 44.

See Dreshta Boghra, The Origins of Maglev Trains, Quark (Soc’y of Physics Students, Tex. Tech Univ. Lubbock, Tex.), Feb. 2022, https://www.depts.ttu.edu/phas/News_and_Events/Quark/TheQuarkFebruary2022.pdf [https://perma.cc/RXR4-8DSV] (discussing the historical development of magnetic trains—sometimes called “maglev”).

John Jacob Astor, A Journey in Other Worlds: A Romance of the Future 17, 49–50 (1894).

U.S. Patent No. 782,312.

Astor, supra note 47, at 49–50; '312 Patent fig. 6, col. 2 ll. 79–92.

Ben Lang, Hands-On: Mojo Vision’s Smart Contact Lens Is Further Along than You Might Think, Road to VR (July 5, 2022), https://www.roadtovr.com/mojo-vision-smart-contact-lens-ar-hands-on/ [https://perma.cc/9RZ4-HMUF].

See Smart Contact Lenses, Technovelgy.com, http://www.technovelgy.com/ct/content.asp?Bnum=1068 [https://perma.cc/9NNT-43NF] (last visited Sep. 6, 2025) (discussing contact lenses with a computer display in Vernor Vinge’s short story Fast Times at Fairmont High (2001), and his novel Rainbows End (2006)).

U.S. Patent No. 10,001,661.

Vernor Vinge, Rainbows End: A Novel with One Foot in the Future 47 (James Frenkel ed., 2006); '661 Patent figs. 5a & 5b, col. 21 ll. 2–15, 31–42.

Robert Heinlein, Methuselah’s Children, Astounding Sci.-Fiction, July 1941, at 9, 10.

Arthur C. Clarke, Imperial Earth 101 (1976).

John Markoff, Google Cars Drive Themselves, in Traffic, N.Y. Times (Oct. 9, 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/10/science/10google.html [https://perma.cc/Y5QL-JHTM].

Ben Cohen, It’s Waymo’s World. We’re All Just Riding in It., Wall St. J. (May 30, 2025, at 20:03 ET), https://www.wsj.com/tech/waymo-cars-self-driving-robotaxi-tesla-uber-0777f570 [https://perma.cc/Y3YE-E2YL]; Can Robotaxis Put Tesla on the Right Road?, Economist (June 11, 2025), https://www.economist.com/business/2025/06/11/can-robotaxis-put-tesla-on-the-right-road [https://perma.cc/9UU6-GEN3]; Uber Is Readying Itself for the Driverless Age—Again, Economist (Aug. 7, 2025), https://www.economist.com/business/2025/08/07/uber-is-readying-itself-for-the-driverless-age-again [https://perma.cc/X6VT-RUR8].

See infra notes 60–64 and accompanying text.

Heinlein, supra note 54, at 10.

U.S. Patent No. 9,508,260.

U.S. Patent No. 10,452,068.

U.S. Patent No. 10,309,789.

Clarke, supra note 55, at 101, 116.

U.S. Patent No. 10,249,194.

Mark A. Lemley, The Myth of the Sole Inventor, 110 Mich. L. Rev. 709, 712–13 (2012).

See id. at 712 (“Multiple, independent studies show that . . . ‘singletons’ are extraordinarily rare sorts of inventions.”(footnote omitted)); supra notes 47–48 and accompanying text.

See Boghra, supra note 46.

Gernsback, supra note 34, at 2; see also Mike Ashley, The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the Beginning to 1950, at 29–30 (2000) (an account of Watson-Watt purportedly claiming that Gernsback was the “real inventor” of radar after being shown Gernsback’s prediction).

H. Gernsback, Ralph 124C 41+, 4 Mod. Elecs. 593, 593 (1911) (emphasis omitted).

Id.

G.B. Patent No. 129,336; Espacenet, *“*Robert Alexander Watson Watt”, 18 results (Sep. 9, 2025) (on file with the Houston Law Review) (showing eighteen patents between 1917 and 1938 that laid the groundwork for radar technology).

Merrill I. Skolnik, History of Radar, Britannica (Nov. 1, 2025), https://www.britannica.com/technology/radar/History-of-radar [https://perma.cc/9ZRH-DDMN].

'336 Patent, supra note 71.

Raymond E. Fielding, Lee de Forest, Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lee-de-Forest [https://perma.cc/C3ZD-9RWS] (last visited Oct. 23, 2025).

Letter from Lee de Forest to Hugo Gernsback (Nov. 27, 1944) (on file with Syracuse University Libraries) [hereinafter Lee de Forest Letter].

Lee de Forest, Foreword to Hugo Gernsback, Ralph 124C 41+, at 15, 18 (2d ed. 1950).

DE Patent No. 165,546; DE Patent No. 169,154; The Telemobiloscope, daidalos, https://www.daidalos.blog/en/innovations/milestones/artikel/the-telemobiloscope/ [https://perma.cc/2FU2-MQGF] (last visited Oct. 23, 2025).

Charles Süsskind, Who Invented Radar?, 9 Endeavour 92, 92–94 (1985).

Ashley, supra note 68, at 30; Daniel Stashower, A Dreamer Who Made Us Fall in Love with the Future, Smithsonian, Aug. 1990, at 44, 48.

Lee de Forest Letter, supra note 75.

See The Perversity of Things, supra note 6, at 2.

Steven Levy, Neal Stephenson Named the Metaverse. Now, He’s Building It, Wired (Sep. 16, 2022, at 09:00 CT), https://www.wired.com/story/plaintext-neal-stephenson-named-the-metaverse-now-hes-building-it/ [https://perma.cc/7GEJ-7ZDD].

U.S. Patent No. 6,285,380 col. 1 ll. 59–67, col. 2 ll. 1–3.

Gene Quinn, Moving from Idea to Patent – When Do You Have an Invention?, IPWatchdog (June 21, 2014, at 13:57 CT), https://ipwatchdog.com/2014/06/21/moving-from-idea-to-patent-when-do-you-have-an-invention/# [https://perma.cc/9584-97EA].

The patent reads, in relevant part:

The novel “Snow Crash” posits a “Metaverse,” a future version of the Internet which appears to its participants as a quasi-physical world. (N. Stephenson, Snow Crash, Bantam Doubleday, New York, 1992.) The participants are represented by fully articulate human figures, or avatars whose body movements are computed automatically by the system. “Snow Crash” touches on the importance of proper authoring tools for avatars, although it does not describe those tools. The present invention takes these notions further, in that it supports autonomous figures that do not directly represent any participant.

'380 Patent, col. 1 ll. 59–67, col. 2 ll. 1–3.

35 U.S.C. §§ 101–103.

Id. § 102(a)(1). Notably, the 1952 Patent Act also included instances of “derivation” as bars to patentability. An invention could be rendered invalid if the inventor “did not himself invent the subject matter sought to be patented.” Id. § 102(f). Thus, in theory, a work of science fiction could have been used to invalidate a patent based on derivation. But derivation as a bar to patentability is not contained in the 2011 Patent Act. Derivation proceedings can be brought under 35 U.S.C. § 135, but only by those who actually filed patent applications or the owners of those applications. Id. § 135.

Daniel H. Brean, Keeping Time Machines and Teleporters in the Public Domain: Fiction as Prior Art for Patent Examination, Pitt. J. Tech. L. & Pol’y, Spring 2007, at 1, 8.

35 U.S.C. § 131.

Katrina Brundage & James Cosgrove, Section 103 Rejections: How Common Are They and How Should You Respond?, IPWatchdog (Oct. 3, 2016, 10:45 CT) https://ipwatchdog.com/2016/10/03/103-rejections-common-respond/ [https://perma.cc/C6PB-4CLA].

Brean, supra note 88, at 7–8.

See 37 C.F.R. § 1.56(a) (2024).

Christopher A. Cotropia, Mark A. Lemley & Bhaven Sampat, Do Applicant Patent Citations Matter? 42 Rsch. Pol’y 844, 844, 847 (2013) (“We find that patent examiners rarely use applicant-submitted art in their rejections to narrow patents, relying almost exclusively on prior art they find themselves.”).

Id. at 847 (Importantly, “the overwhelming majority of art that appears on the face of the patent is not in fact discussed in the course of patent prosecution or used as the basis for a prior art rejection.”).

See Lidiya Mishchenko, Thank You for Not Publishing (Unexamined Patent Applications), 47 BYU L. Rev. 1563, 1587–88 (2022).

See Brean, supra note 88, at 3–4, 16–17.

Robert A. Heinlein, Stranger in a Strange Land 11, 15 (1961).

See Brean, supra note 88, at 3–4, 16–17.

U.S. Patent No. 3,585,356; see Brean, supra note 88, at 8.

See Stephen Yelderman, Prior Art in the District Court, 95 Notre Dame L. Rev. 837, 862–63 (2019).

Roger Allan Ford, Patent Invalidity Versus Noninfringement, 99 Corn. L. Rev. 71, 78 (2013).

Sean Ludwig, Samsung Cites Kubrick’s ‘2001’ as Legal Defense in Apple Patent Battle, VentureBeat (Aug. 23, 2011), https://venturebeat.com/mobile/samsung-kubrick-2001-apple-patent-war/ [https://perma.cc/N28X-L3R6]; see also John Uri, 50 Years Ago: 1968 Welcomed 2001, NASA (Apr. 5, 2018), https://www.nasa.gov/history/50-years-ago-1968-welcomed-2001/ [https://perma.cc/YLU5-PEPQ] (detailing Kubrick and Clarke’s collaboration to create 2001: A Space Oddity).

Samsung cited Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in an opposition brief to Apple’s motion for a preliminary injunction. The opposition brief was filed under seal, but you can see parts of it and attached imagery online. See Ludwig, supra note 102; Eingestellt von Florian Mueller, Samsung Cites Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ Movie as Prior Art Against iPad Design Patent, Foss Patents (Aug. 23, 2011, at 17:42 CT), http://www.fosspatents.com/2011/08/samsung-cites-stanley-kubricks-2001.html [https://perma.cc/7GAY-WZP9]. Notably, Apple’s patent at issue was a design patent that covered the ornamental appearance of the iPad device, rather than its underlying functionality. Hence, the relevant features were the aesthetics of the tablets in the film (the rectangular shape, the dominant display screen, the narrow borders, and the flat front surface), not how they were depicted to work in the movie. See U.S. Design Patent No. D618,677 (“Electronic Device”); U.S. Design Patent No. D593,087 (“Electronic Device”); U.S. Design Patent No. D504,889 (“Electronic Device”); U.S. Patent No. 7,469,381 (“List Scrolling and Document Translation, Scaling, and Rotation on a Touch-Screen Display”).

35 U.S.C. § 112.

Id.; see also Janet Freilich, Ignoring Information Quality, 89 Fordham L. Rev. 2113, 2124 (2021) (describing how examiners evaluate whether disclosure in prior art enables an invention); Seymore, supra note 25, at 385–87 (listing factors relevant to enablement analysis). “[T]he enablement bar is in certain respects more lenient for prior art than for patent applications.” Hrdy & Brean, supra note 4, at 30.

Science fiction inventions typically lack a credible utility, because they are typically inoperable and have minimal support in contemporary science at the time they are described. Hrdy & Brean, supra note 4, at 24–25.

Raytheon Techs. Corp. v. Gen. Elec. Co., 993 F.3d 1374, 1380–81 (Fed. Cir. 2021).

In re Bigio, 381 F.3d 1320, 1325 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

See Gernsback, supra note 34, at 67.

Cotropia, Lemley & Sampat, supra note 93, at 845.

37 C.F.R. § 1.56.

See Brean, supra note 88, at 3–4, 16.

Cotropia, Lemley & Sampat, supra note 93, at 847.

Mark A. Lemley, Rational Ignorance at the Patent Office, 95 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1495, 1500 (2001); see also Michael D. Frakes & Melissa F. Wasserman, Is the Time Allocated to Review Patent Applications Inducing Examiners to Grant Invalid Patents?: Evidence from Micro-Level Application Data 8–9 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 20337, 2014) (stating that examiners spend nineteen hours on average per application, with variation based on technology area).

See infra notes 118–34 and accompanying text.

Gary K. Wolfe, How Great Science Fiction Works 14–15 (2016).

RU Patent No. 2733449C1.

The patent reads, in relevant part:

In his 1865 book “From the Earth to the Moon” Jules Vern proposed a gun to launch people to the moon. The idea of a “Super Gun” to launch objects into space became a reality in the 1960s when a team lead by Dr Gerald Bull successfully launched small satellites into space.

U.S. Patent Publication No. 2006/0032986 paras. [0011]–[0018].

U.S. Patent No. 3,302,463 fig. 1., col. 1 ll. 9–24.

Id. col. 1 ll. 18–27.

The patent recites, for instance, that Verne’s book From the Earth to the Moon “deals in some detail with problems of life support, reentry, and missile recovery.” Id. col. 1 ll. 22–27.

Google Pats., “Isaac Asimov”, 75 results (Oct. 2, 2025) (on file with the Houston Law Review).

See infra examples at notes 124–34.