- I. Introduction

- II. Corporate Law Federalism and Delaware’s Historical Dominance

- III. Navigating Home State Incorporation: Understanding Preferences Among Private Firms

- IV. Delaware’s Influence on Corporate Governance

- A. Delaware’s Dominance in the Unicorn Race

- B. Venture Capital Lawyers’ Critique of Delaware Courts Over the Moelis Decision

- C. Employees as Common Shareholders and Stock-Option Holders

- D. Delineating the Impact of Securities Law Amendments on Delaware’s Corporate Landscape

- E. Shifts in Common Shareholder Dynamics: Evolution and Impact on Delaware’s Corporate Realm

- F. Evaluating Delaware’s Role in Safeguarding Employee Shareholder Interests

- V. Conclusion

I. Introduction

“[C]lose corporations generally incorporate in the states in which their principal places of business are located, the state competition debate has naturally focused on publicly traded companies.”

–Lucian Arye Bebchuk[1]

“The Times They Are a-Changin’.”[2] We live in a new era. One in which private firms now surpass public ones, challenging the conventional scholarly focus on public companies. This Article addresses this shift in our corporate landscape. Scholars, who once paid limited to no attention to privately held firms, are now prompted to reconsider their focus.[3]

In the United States, businesses are established and regulated at the state level rather than the federal level.[4] Consequently, early on, entrepreneurs must make the critical decision of where to incorporate their business. Due to its business-friendly laws and strong corporate governance infrastructure, Delaware stands out as the preferred destination for public companies.[5] The state actively works to uphold its position as the foremost location in the United States and globally for business incorporation.[6]

While existing research has predominantly focused on public firms, a significant gap persists in understanding how this market for corporate law influences the organizational structure and governance of large private firms, colloquially referred to as “unicorns.”[7]

This Article seeks to address this gap by offering fresh insights and groundbreaking findings through empirical analysis and data on unicorns’ incorporation and headquarter choices. A significant finding reveals that 97% of unicorn entities choose to incorporate in Delaware.[8] This discovery is groundbreaking, as it diverges significantly from incorporation patterns seen in other sectors of the business world. By closely examining the competition for unicorn charters in the United States, this Article not only contributes depth and breadth to the scholarly understanding of the market for corporate law but also sheds light on the distinctive decision-making processes of some of the economy’s largest and most influential firms. This exploration aims to unravel the factors driving the exceptional pattern of Delaware incorporation among unicorn firms and its implications for the broader corporate landscape.

The prevailing wisdom in the literature on corporate chartering in the United States has long emphasized Delaware’s prominence, particularly within the realm of public firms.[9] However, a notable gap in this narrative pertains to the prevailing assumption that this dominance does not extend to private firms.[10] The conventional wisdom suggests that private entities typically favor incorporating in their respective home states where their primary place of business is located.[11] This Article seeks to challenge and reevaluate this established narrative, directing attention to a distinct and remarkable new category of unicorn companies.

Why unicorns? Unicorn firms are characterized by their extraordinary high and perhaps exaggerated valuations exceeding $1 billion.[12] These new types of very large or gigantic privately held venture-backed innovation-driven firms have emerged as a unique subset within the corporate landscape. However, the distinctiveness of unicorns extends beyond their impressive valuation. This Article adds another layer to their definition by characterizing unicorns as entities inclined to remain private for longer periods of time, displaying a resistance to traditional exit strategies, such as an initial public offering (IPO).[13]

Discussions surrounding corporate chartering have overlooked the preferences and considerations of such high-valuation private companies. By delving into the chartering choices of unicorn firms, this Article aims to offer a nuanced perspective that challenges the existing assumptions regarding the dominance of Delaware in the private sector. This investigation aims to empirically scrutinize whether unicorn firms deviate from the assumed pattern of privately held firms incorporating in their home states, choosing instead to emulate their public counterparts by selecting Delaware as their preferred jurisdiction. The exploration into these intricacies raises questions about whether Delaware’s distinctive allure for out-of-state incorporations for publicly held firms extends to large privately held firms such as unicorns.

When examining the corporate charters of a selected sample of unicorn firms, a notable, remarkable finding surfaces: an overwhelming 97% of these entities choose Delaware as their state of incorporation.[14] This important groundbreaking finding not only signifies a substantial deviation from incorporation patterns observed in other segments of the business environment but also prompts essential inquiries into the specific factors shaping the decisions of unicorn firms in the realm of corporate governance.

The distinctive inclination of unicorns towards Delaware becomes particularly evident when contrasted with the incorporation rates observed among public firms. While only 68.2% of Fortune 500 members select Delaware as their state of incorporation, it is noteworthy that around 79% of “all U.S. initial public offerings in the calendar year 2022 were registered in Delaware.”[15] So, 97% is much higher.

Further underscoring the uniqueness of unicorn firms, this stark contrast becomes even more pronounced when juxtaposed with earlier studies focusing on different categories of private entities. For instance, early-stage venture-backed private firms exhibit a 67% incorporation rate in Delaware,[16] while small private enterprises demonstrate a mere 2%.[17] It is important to note that unicorns are private firms, and the overwhelming favoritism towards Delaware among them emerges as an unprecedented trend, highlighting the distinctiveness of these entities in shaping their corporate destinies. This remarkable discrepancy not only underscores the importance of understanding the dynamics driving unicorn firms’ incorporation choices but also prompts a detailed exploration into the contributing factors behind this unusually high rate of Delaware incorporation.

Beyond this intriguing phenomenon, a broader context of concern revolves around the regulation of unicorns—entities significant enough to have a public impact while remaining within the private domain. The concentration of these influential firms in Delaware endows the state with substantial leverage to influence regulatory frameworks, particularly in terms of safeguarding the interests of common shareholders and stock-option holders, who may lack the means to protect themselves through contractual agreements.

Understanding the chartering preferences of unicorn firms is crucial as they represent a dynamic and influential segment of the business world. These companies, often at the forefront of innovation and disruption, may adopt distinctive strategies in their choice of jurisdiction for incorporation. Examining the factors influencing their decisions can provide valuable insights into the evolving dynamics of corporate governance, regulatory considerations, and the strategic advantages that specific jurisdictions may offer to such high-profile entities.

Moreover, considering the absolute majority of private or closely held firms becomes integral to the narrative. While Delaware’s dominance in public firms is well-documented,[18] exploring whether this trend persists among private or closely held firms adds another layer of complexity to the analysis. This Article aims to investigate whether the assumed preference for home state incorporation holds true not only for unicorn firms but also for the broader landscape of private companies.

By focusing on unicorn firms and extending the discussion to encompass the absolute majority of private or closely held firms, this Article aims to contribute to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of corporate chartering practices in the United States. It seeks to explore whether the assumed preference for home state incorporation holds true for this exceptional category of companies and whether similar patterns emerge in the broader private sector. Through empirical analysis and case studies, this research endeavors to shed light on the factors influencing the chartering decisions of private or closely held firms, adding depth to the scholarly conversation and providing insights into the intricate dynamics of corporate governance in the contemporary business environment.

This Article will focus on Delaware’s responsibility in regulating the relationships between shareholders and management in private firms due to information asymmetry in private markets, specifically, on behalf of employees as common shareholders and stock-option holders, which can be viewed as a mechanism to protect employees—a demographic that may encounter challenges in adequately safeguarding their interests through contractual arrangements alone. This dynamic underscores the far-reaching implications of Delaware’s dominance in corporate chartering for the broader landscape of corporate governance and regulation.

Upon completion of the empirical analysis, several critical variables were identified as key factors attracting unicorns to incorporate in Delaware, distinguishing it from other states. One particular variable concerning the publication of a model charter by the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) in 2003 emerges as influential in drawing unicorns to choose Delaware over alternative jurisdictions.[19]

The adoption of standardized documents, endorsed by industry experts, adds an extra layer of familiarity and consistency for both investors and companies during transactions. Furthermore, Delaware’s appeal may extend to its ability to attract out-of-state investors.[20] Unicorns, being high-profile entities with diverse investor bases, may find Delaware’s legal landscape conducive to accommodating investors from various geographical locations. This aligns with the theory that these companies leverage Delaware’s reputation and legal framework to attract a broader pool of investors, further solidifying its status as the preferred jurisdiction for unicorn incorporation.

Another significant variable is that these unicorn companies are often deeply integrated into networks involving repeat players in the venture capital and startup ecosystem. The prevalence of repeat players, such as serial entrepreneurs as founders, and other experienced repeat players, including venture capitalists, legal advisors, and corporate governance experts who are familiar with Delaware’s corporate laws, may influence this decision-making process. The established precedents and case law in Delaware provide a level of predictability and familiarity that benefits these repeat players. The variables are explained in greater detail below and contribute to the adoption of Delaware as the state of choice for unicorn firms.[21]

This Article analyzes these factors as they relate to high-valuation startups in the context of the renewed debate surrounding competitive federalism. In essence, Delaware’s corporate legal structure and the incorporation essentials it offers align seamlessly with the distinctive requirements of unicorns.

This Article is structured as follows. Part II, “Corporate Law Federalism and Delaware’s Historical Dominance,” explores Delaware’s historical dominance as a preferred jurisdiction for public companies. It decodes the features that make Delaware a corporate haven for large publicly traded firms, delves into the debate surrounding a “race-to-the-top” or “race-to-the-bottom” theory, and highlights the often-overlooked role of privately held entities in the discourse on state corporate law competition. It also analyzes the transformative shift in corporate dynamics, emphasizing the decline in public markets, the historical evolving focus on public firms, and a comparative analysis of public and private entities. Additionally, it provides insights into the new changing strategies and ownership structures within the corporate landscape.

Contrary to the notion that private companies primarily incorporate in their home state, this is not true for unicorn firms.[22] This research challenges these conventional notions and examines motivations for choosing to incorporate in Delaware rather than home states. This Article further contributes to the broader debate on state charter competition, questioning whether it fosters a “race to the top” or “race to the bottom.”[23] It also addresses the longstanding question of whether states adopt corporate laws favoring managers over shareholders, offering new perspectives and groundbreaking insights into the dynamics of unicorn incorporation choices.[24]

Part III, “Navigating Home State Incorporation: Understanding Preferences Among Private Firms,” focuses on understanding variations among private firms, clearing the terminological landscape, and scrutinizing previous data on private firm incorporation. New unicorn data is presented, exploring data collection methodologies, key insights, implications, challenges, and additional contextual data.

It relies on a primary dataset consisting of 220 unicorn firms, with a focus on those based in the United States.[25] The data collection process entailed extracting relevant information to analyze variables influencing their incorporation decisions. This dataset serves as the foundation for understanding patterns and trends concerning the preferred jurisdictions for unicorn incorporation.

Part IV, “Delaware’s Influence on Corporate Governance,” delves into Delaware’s influence on unicorn firms’ corporate governance. It examines Delaware’s dominance in the unicorn race, the role of employees as common shareholders and stock-option holders, the impact of securities law amendments, shifts in common shareholder dynamics, and Delaware’s role in safeguarding employee shareholder interests.

Part V concludes with a comprehensive understanding of the unique corporate governance landscape shaped by Delaware’s historical dominance and the distinctive characteristics of unicorn firms.

II. Corporate Law Federalism and Delaware’s Historical Dominance

Corporate law federalism refers to the division of regulatory authority between state and federal governments concerning corporate governance. In this context, Delaware has historically played a predominant role in overseeing public companies. This dominance is rooted in Delaware’s business-friendly legal framework, which includes a specialized court system and well-established corporate statutes. These attributes have made Delaware an attractive jurisdiction for companies seeking incorporation.

The following is an explanation of the historical trend of why public companies favor Delaware.

A. The Allure of Delaware for Public Companies

Delaware historically dominated the publicly held corporate-chartering market in the United States.[26] Currently, it stands as the only state drawing a significant number of out-of-state headquartered publicly held companies for incorporation. At the heart of an age-old debate in American corporate law literature lies the question of why public companies consistently choose Delaware as their preferred state of incorporation.[27] This topic represents one of the most extensively discussed and debated subjects in the realm of corporate charter competition.[28] This body of literature is fueled, to a significant extent, by differing opinions regarding the normative desirability of companies having the ability to choose among various corporate laws.

The tradition of horizontal corporate law federalism is deeply rooted in American history, whereby a firm located and headquartered in a particular state is generally permitted to incorporate in any other state and thereby have its internal affairs governed by that other state’s corporate law.[29]

Consequently, the choices for incorporation follow a “bimodal” pattern,[30] where public and private firms commonly opt for either home-state or Delaware incorporation.[31] The majority of public firms and large private enterprises tend to choose Delaware.[32]

1. Decoding Delaware: Features that Make It a Corporate Haven

In the United States, companies have the freedom “to establish their corporate entities in any state” within the federation, irrespective of their operational activities in that specific state.[33] This creates a scenario of interstate competition as states actively compete to attract businesses for incorporation, leading to the generation of revenue through mechanisms such as franchise taxes and various fees. Termed “competitive federalism,” this approach places states at the center, empowering them to formulate and enforce their unique set of corporate laws and regulations.[34]

Corporate law federalism refers to the division of authority between the federal government and individual states in regulating corporate activities.[35] In the United States, the federal government and state governments share the power to regulate corporations.[36] While federal laws, such as securities laws, apply uniformly across the country, each state has the authority to enact its own corporate laws, particularly those related to the internal affairs of corporations.[37]

Delaware has historically been the preferred state for the incorporation of many public companies. The reasons behind Delaware’s dominance can be attributed to several factors. Most scholars concur on the following factors: First, Delaware offers a business-friendly legal environment with a well-established body of corporate law that provides clarity and predictability for businesses. The state has a specialized court, the Delaware Court of Chancery, which focuses exclusively on corporate matters and has experienced judges, contributing to the efficient resolution of corporate disputes.[38]

Second, Delaware has a responsive and flexible legislative process that allows for quick updates to corporate laws to address emerging business needs. This adaptability attracts companies seeking a favorable regulatory environment.[39]

Third, Delaware’s legal precedents and decisions have created a body of case law that provides further guidance and certainty for businesses operating under Delaware law. This has established Delaware as a jurisdiction of choice for corporate incorporation, with a significant majority of Fortune 500 companies choosing Delaware as their legal home.[40] Fourth, antitakeover statutes.[41] Finally, the state also offers a variety of corporate structures and favorable tax treatment.[42]

However, there is a long debate on whether Delaware’s corporate law is shareholder-friendly or management-friendly and provides strong protection for directors and officers, which is appealing to companies and their leadership.

The following is a short overview of this debate.

2. Debating Between a “Race to the Top” or a “Race to the Bottom”—Shareholder or Management Friendly?

Understanding why public companies choose Delaware over other states is important, as the dual role of corporate law serves as a crucial element in our economy. Viewing corporate law as a product involves recognizing that the legal frameworks and services provided to businesses as essential components contribute to the overall function of the business environment.[43] This dual role involves both rationalizing economic behavior and adapting to the ever-changing landscape of technological and innovation dynamics.[44] This dynamic nature reflects the evolving needs and challenges faced by corporations, underscoring the vital importance of corporate law in providing a framework that accommodates these changes and shapes organizational structures and governance models.[45]

The impact of chartering decisions on a company’s norms and corporate governance structures cannot be overstated. The ongoing debate surrounding state charter competition focuses on whether states are adopting corporate laws that prioritize managers over shareholders, leading to extensive empirical research on publicly held corporations.[46] At the core of this debate is the question of whether state chartering competition aligns more with a race-to-the-bottom or a race-to-the-top theory of corporate law.[47]

From the viewpoint of a race-to-the-top perspective, companies opt to incorporate in Delaware because its laws are believed to optimize firm value for shareholders.[48] In contrast, the race-to-the-bottom perspective proposes that companies choose Delaware due to its inclination toward favoring firm insiders at the detriment of others.[49]

Alternative perspectives on why a firm might choose Delaware shift away from the intrinsic quality of its laws, focusing instead on the number of other companies incorporated in Delaware.[50] Drawing from the network effects literature, Klausner argues that some firms commit to Delaware as a long-term domicile, especially those planning future IPOs.[51] This decision may not necessarily stem from an evaluation of Delaware’s corporate laws but rather anticipates a large number of other public firms being domiciled in Delaware in the future.[52] The extensive and sustained network of Delaware firms ensures access to a richer body of case law and superior legal services compared to domiciling in their home state, where the firm network is relatively smaller.[53]

Furthermore, according to Kahan and Klausner, the persistence of contractual terms in loan agreements, charters, and similar documents may not solely be due to their inherent quality, but rather because of the learning advantages derived from their widespread use.[54] These advantages encompass increased efficiency in drafting and a decrease in uncertainty.[55] Their analysis suggests that a firm might choose Delaware as its domicile not only for the state’s attributes but also for the learning benefits generated by the historical choices of numerous other firms that have selected Delaware.[56]

Regardless, the prevailing discourse surrounding state competition in corporate law primarily focuses on publicly traded firms while overlooking privately held entities.[57] The fundamental argument posits that the decision-making processes of privately held firms differ significantly from those of their publicly traded counterparts, warranting a distinct analytical approach.[58]

The following addresses the gap in the literature and provides a fresh perspective, new insights, and groundbreaking findings.

3. Examining the Neglected Role of Privately Held Entities in State Corporate Law Competition Discourse

The prevailing discourse surrounding state competition in corporate law primarily focuses on publicly traded firms while overlooking privately held entities.[59]

A gap in the existing literature pertains to the limited understanding of how the market for corporate law influences the organizational structure and governance of large privately held corporations. Notably, there is a lack of specific research on the incorporation decisions of the most significant privately held entities in our economy, commonly referred to as unicorns. Scholars typically refrained from exploring private firms, asserting that the decision-making processes of privately held entities diverge significantly from those of publicly traded counterparts. This distinction therefore necessitates a unique analytical approach to comprehensively address the dynamics within privately held corporations.[60]

B. Private Becomes the New Public: Transformative Shift in Corporate Dynamics

The inattention to privately held firms by scholars can be seen as somewhat expected, given that only in the last decade, approximately, has there been a notable transformation in the market dynamics.[61]

1. Public Market Decline: Changes to Corporate Ownership.

Private firms have not only surpassed but have also outperformed their public counterparts.[62] To illustrate, one might metaphorically depict public firms as a species currently facing extinction.[63] The number of public firms is dwindling, they are raising less capital from public markets, and dissolution is occurring at a faster rate than ever before.[64]

This trend, spanning several decades, elucidates a significant decline in the count of publicly traded U.S. companies. In 1996, the United States boasted a peak of 8,090 listed companies. Unfortunately, as of the first quarter of 2023, this number has sharply declined to 4,572, representing a staggering 43% decrease.[65]

Private companies, on the other hand, are experiencing significant growth, securing substantial capital from private markets and opting to remain private for extended durations.[66] Only in the past eleven years have we seen a substantial growth in unicorn firms, which aim to prolong their status as privately held entities for as long as feasible.[67] Unicorns, as a unique category of high-valuation startups, possess distinct characteristics that set them apart from other startups or close large privately held corporations or public ones.[68]

Originally coined to underscore the exceptional success and rarity of such companies in the competitive business landscape, the term “unicorn” highlights the scarcity of achieving such a high valuation of $1 billion before going public or being acquired.[69] However, the once-rare occurrence of unicorn firms has become more prevalent. As of February 1, 2025, the global count of unicorn companies was 1,434, signaling a remarkable surge in these privately held startups.[70]

There is a notable shift within the technology sector, where certain tech giants, exemplified by figures like Elon Musk, no longer pursue public status.[71] This new phenomenon is both intriguing and challenges our conventional understanding of how privately held firms operate. It specifically focuses on the operational dynamics of long-term privately held venture-capital backed startup companies. This Article introduces the innovative concept of recognizing a new classification—the “long-term private giant” company[72]—citing examples such as Elon Musk’s corporations: xAI, X Corp., X Holdings, Neuralink and more.[73] This idea initiates an interesting analysis of how different states compete to attract these companies, marking a departure from viewing unicorns merely as a transitional phase before going public. These entities now have a more enduring or long-term status, which is primarily tied to the changes listed below in our federal securities laws and their effect on our state corporate laws.

These market developments explain the void in literature regarding the effect of the corporate law market for charters on the organizational structure and governance of large privately held corporations. Notably, there is a lack of research specifically exploring the incorporation decisions of unicorns.

2. Public Firm Focus: Evolving Dynamics of Corporate Strategies.

Historically, public firms garnered more attention than private firms, driven by the belief in their significant impact on the economy.[74] Many law schools in the United States emphasize public firms in business association (corporate law) courses, assuming that law students will predominantly work for large law firms representing these entities post-graduation.[75] Undoubtedly, public firms have been pivotal drivers of economic growth, shaping the social and environmental landscape. Their crucial role in mobilizing capital, job creation, fostering innovation, providing investment opportunities, and promoting transparency and accountability cannot be overstated.

The following are additional reasons why researchers often focus on public firms. First, information on public firms is generally more readily available compared to private firms. Due to the regulatory environment, publicly traded companies are required to disclose financial statements, governance practices, and other relevant information to regulatory bodies and the public.[76] This transparency makes it easier for researchers to access comprehensive and standardized data.

Second, researchers studying public firms can gain insights into market dynamics, investor behavior, and the overall economy.[77] Third, corporate governance literature focuses on structures of public firms. It explores the impact of board structures, executive compensation, and shareholder activism.[78] Fourth, thanks to U.S. securities laws, public firms are required to communicate policy and actions with their shareholders and the broader market.[79] Finally, researchers can analyze stock market movement and reactions to significant events, such as news, earnings announcements, mergers and acquisitions, and other corporate events.[80]

While public companies often take center stage in the news, corporate governance and finance literature, or law school courses, it is crucial to recognize that the foundational principles of corporate law apply equally to both private and public firms.[81] Let’s turn to private firms.

Privately held companies, although sometimes overshadowed, wield considerable influence on our economy, business development, and entrepreneurship. The ongoing shift from public to private firms has heightened the importance of understanding the role of private entities in society. This transition carries substantial implications for corporate law and governance. Analyzing the decisions of large private firms becomes essential in comprehending the patterns of incorporation and the outcomes of regulatory competition in areas like information disclosure, corporate governance, and securities.

3. A Comparative Analysis of Public and Private Firms.

Recognizing the disparities between public and large venture capital-backed (VC-backed) private firms is essential when assessing incorporation preferences, as these distinctions profoundly influence the legal framework for each entity. Within the legal environment, privately held companies exhibit unique characteristics that necessitate careful consideration. Here are some primary distinctions:

First, private companies typically have fewer disclosure requirements compared to their public counterparts. They are not obligated to disclose financial information to the general public, enabling greater confidentiality in their operations.[82] Second, as elaborated in greater detail below, the governance structures of private firms can exhibit significant variation. While some may adopt governance practices akin to public companies, others—especially closely held or family-owned businesses—might embrace more flexible governance arrangements.

Third, private firms often rely on shareholder agreements to delineate the rights and responsibilities of shareholders, embracing a practice known as private ordering. In this context, private ordering allows companies to tailor their governance structures to the specific needs and preferences of the involved parties, providing flexibility and customization in defining the terms of shareholder relationships.[83] This approach enables private firms to navigate their unique circumstances and align governance arrangements with the distinct characteristics and goals of the business.[84] Fourth, private companies face more restricted access to capital sources, loans, and funding. Securing loans can be challenging due to the absence of tangible assets, primarily relying on intangible assets, which can limit the collateral options for lenders. This limitation contrasts with public companies, which often shave more diverse financing avenues.[85] In the startup arena, these companies commonly depend on private equity, venture capital, or other alternative funding sources to fulfill their capital requirements.[86]

Fifth, in recent times, however, there has been a notable surge in alternative financing mechanisms, accompanied by the emergence of new market trends, often in response to the challenges of securing venture capital investments.[87] Mutual funds and sovereign wealth funds, among other new market participants, are now injecting substantial capital into unicorn firms. These new market dynamics contribute to the prevailing trend of unicorn firms postponing their IPOs.[88]

The involvement of these new players and others alters the equilibrium, empowering founders to request more founder-friendly funding rounds.[89] Securing capital for a startup, even one situated in Silicon Valley with venture capital backing, remains an exceedingly risky and challenging undertaking.[90] These private investments enable the firm’s founder to postpone the expenses linked to going public and evade the pressures associated with being a public company.[91] This is particularly crucial in avoiding the pressures to refrain from investing in innovation and instead focus on short-term results.[92]

To sum up, this analysis has broader implications for the current landscape of corporate law, the potential need for future federal intervention, and the overarching theories of regulatory competition.

Having underscored the significance of privately held firms in our economy, let’s now redirect our attention to debunking another misconception, specifically, the notion that all privately held firms are identical, including the misconception that they share the same preferences when it comes to incorporation choices.

III. Navigating Home State Incorporation: Understanding Preferences Among Private Firms

In the complex landscape of horizontal federal corporate chartering competition, private firms also grapple with critical decisions surrounding home state versus Delaware incorporation. Contrary to a common misconception, these privately held entities are far from uniform in their preferences and approaches.

As we delve into the nuanced realm of home state incorporation choices among private firms, it becomes evident that a diverse array of factors shapes their decisions. This exploration aims to shed light on the multifaceted factors influencing the incorporation choices of private firms, emphasizing the intricate interplay between home state options and the renowned allure of Delaware as a preferred jurisdiction.

Indeed, our exploration will reveal that unicorns exhibit distinct behaviors and considerations, setting them apart from other privately held firms.

A. Understanding Variations Among Private Firms

The diversity among private companies is undeniable,[93] and a nuanced examination becomes crucial to understanding the broader landscape. While Delaware’s dominance in public firms is well established, investigating whether this trend extends to large private firms introduces additional layers of complexity to the analysis.

1. Clearing the Terminological Landscape.

This Article delves into the nuanced distinctions within private companies, aiming to discern the underlying reasons for the presumed inclination toward home state incorporation, particularly for small or closely held firms. The investigation seeks to explore whether this tendency extends across the broader spectrum of other private enterprises.

By concentrating on unicorn firms and comparing them to private or closely held entities, this Article contributes to a more thorough and nuanced comprehension of corporate chartering practices in the United States. It seeks to unravel why the perceived preference for home state incorporation does not hold true for this exceptional category of companies. Through empirical analysis and case studies, this research endeavors to illuminate the factors influencing the chartering decisions of unicorn firms, enriching scholarly discussions and providing valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of corporate governance in the contemporary business landscape.

Let’s start with terminology. Traditional corporate literature often tends to broadly categorize companies as either “public” or “close” corporations,[94] oversimplified distinctions that hinder clear policymaking. The term “‘close corporation’ itself [also] embodies . . . ambiguity . . . sometimes [signifying a] ‘closed corporation,’ [or other] times [a] ‘closely-held corporation,’ [or occasionally] both.”[95] It’s crucial to recognize that private companies vary significantly.

Some private companies may have freely tradable shares on secondary markets. Additionally, corporations with non-freely tradable shares may still have hundreds or thousands of shareholders, deviating notably from a “typical closely held corporation[, which usually] has only a [few] shareholders, [often, but not limited to,] from the same family.”[96]

As noted above, the terms “closed” or “private” corporations will usually be applied to those firms imposing some restrictions on share tradability. Within this broad categorization, two critical distinctions are considered. First, “a [company with] shares . . . held by a small [group] of individuals[, where] interpersonal relationships [play a vital] management [role, will be characterized] as ‘closely held,’”[97] contrasting with the term “privately held,” which implies a company not listed on an exchange but widely held by numerous shareholders.[98] Again, privately held firms may have some tradability on secondary markets.

Furthermore, a crucial distinction needs to be made for the purposes of this Article between VC-backed privately held firms and other types of privately held firms. This Article focuses exclusively on VC-backed firms, which are often involved in high-tech or knowledge-intensive industries such as technology, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and other sectors requiring advanced scientific or technological expertise.[99] These firms play a pivotal role in job creation, technological innovation, and overall economic stimulation in the United States, contributing significantly to total output and employing a substantial number of skilled workers, thereby elevating wages across various job sectors.[100]

Certainly, now that the terminology is established, let’s proceed to debunking previous data and research results. There is no significant data or research concerning the incorporation decisions made by the largest closely held U.S. corporations—unicorns.[101]

The subsequent overview delves into the limited research conducted with regards to privately held firms, the difference between unicorns and other types of private firms, this subject’s research, and the findings derived from it.

B. Unraveling Preconceptions: Scrutinizing Previous Data

Competition among states for the charters of privately held firms was traditionally viewed as minimal by corporate law scholars. This perception stemmed from the tendency of these firms to operate within a single state, with the associated costs of incorporating in other jurisdictions often cited as outweighing the potential benefits for such businesses.[102]

Over the years, scholars simply claimed that a significant majority of privately or closely held corporations prefer to incorporate in their local jurisdiction. These scholars include Eisenberg,[103] Kahan and Kamar,[104] Bebchuk,[105] Skeel,[106] and Stevenson.[107] However, to my knowledge, these assertions were stated without substantial empirical investigation. There was no distinction between the different types of private firms. They primarily relied on the scholarship of Ayres.

In 1992, Ayres conducted the most extensive evaluation of how the charter market influenced closely held U.S. corporations.[108] Ayres argued that there is essentially no necessity for closely held corporations to incorporate in another state outside their primary place of business.[109] This is because state law typically offers sufficient flexibility, enabling privately held corporations to establish the structure they prefer.[110] Ayres further asserted that the legal framework for closely held corporations tends to be more flexible than the law governing public corporations.[111] This heightened flexibility, according to Ayres, could potentially obviate the necessity to incorporate out of state for privately held corporations.[112] Kades’s work is also often mentioned, along with Ayres.[113] Kades built on Ayres’s work, suggesting that private firms are opting for incorporation in the state where their primary place of business is located because it is preferable for closely held corporations.[114]

The initial focus on distinguishing between various types of privately held firms emerged in scholarly discussions around 2008. Scholars Rock and Kane became pioneers in incorporating startup firms into their research, marking a pivotal development in understanding the nuances within the realm of privately held entities.[115] Kane and Rock examined a study examining startups operating in Silicon Valley, the prominent U.S. startup hub. Their findings revealed that these firms typically opted to incorporate in California during their initial stages.[116] However, a notable shift occurred when these companies transitioned to the stage of going public. Many of them chose to change their legal domicile to Delaware during this phase.[117] Rock and Kane’s observation aligns with a broader trend identified three years later by Dammann and Schündeln in 2011.[118]

In 2011, Dammann and Schündeln undertook an extensive empirical study on privately held firms, a precursor to the widespread emergence of unicorns in subsequent years.[119] This study made significant contributions to the literature. Let’s review their findings. It’s important to note that their study was conducted before the widespread emergence of unicorn firms.

Initially, they found that, in general, the majority, 95.66%, of small privately held companies (between 20 and 99 employees) in their research established their legal status in the same state as their primary business headquarters, aligning with the assertions of earlier scholars mentioned above.[120] Only 2% of these companies incorporated in Delaware; however, a noteworthy shift emerged when they segmented the dataset and looked only at large private corporations employing over 1,000 employees.[121]

In this subset, only half, 50%, of private companies with over 1,000 employees chose to incorporate in the state where their main business operations were located.[122] Among those opting for incorporation in a different state, more than half selected Delaware.[123] The study also revealed consistent evidence suggesting that private companies originating from states with an unfavorably perceived judiciary were more inclined to incorporate outside of their primary business location.[124] See chart below with the full explanation of their findings.

In 2014, Fried, Broughman, and Ibrahim expanded the work of Dammann and Schündeln, focusing on startup firms.[125] Again, it is important to note that their study was also conducted before the widespread emergence of unicorn firms. Their sample included 1,998 firms, all U.S.-based startups that secured their initial round of venture capital investment between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2002, and received a minimum of $5 million in total venture capital financing across all investment rounds.[126]

The findings of Fried, Broughman, and Ibrahim indicate that startup firms, like other firms, often face a binary decision, opting to incorporate either in their home state or in Delaware.[127] As depicted in Table 2 of their research paper, the majority of sample firms, specifically 67.8% of the same firms, chose Delaware as their initial state of incorporation.[128] Among the remaining firms, 32.2%, that did not choose Delaware, a significant portion, specifically 28.7%, incorporated in their respective home states. Only a minor fraction, 3.5%, of the sample firms opted to incorporate in a jurisdiction other than Delaware or their home state.[129]

If we compare previous research by Dammann and Schündeln, Fried, Broughman, and Ibrahim’s research also highlights that larger firms exhibit a greater likelihood of incorporating in Delaware, consequently reducing the likelihood of incorporating in their home state.[130]

Let’s draw comparisons among the results obtained by this Article’s research, the Dammann study, and the Fried study. Dammann’s databases and Fried’s databases, notably predating the era of unicorn firms, differ in their scopes. Dammann’s database lacks a clear distinction between small private firms and startups, grouping all firms into a singular database.[131] While Dammann does differentiate between sizes within privately owned firms, Fried’s research specifically focuses on early-stage startups and does not encompass mature or large startups that have received early rounds of financing.[132]

Dammann’s findings emphasize the relevance of size for privately held firms. In general, the majority of privately held firms tend to incorporate in the state where they are headquartered.[133] Furthermore, Dammann notes that size indeed matters, with large firms featuring a substantial number of employees showing a distinct trend. Specifically, 57% of large firms with about 1,000 to 4,999 employees, and 41% of very large firms with over 5,000 employees choose to remain incorporated in their primary state of business.[134] For those incorporated outside their primary state of business, around 80% opt for Delaware, indicating a prevalent choice among larger entities.[135] In contrast, Fried’s research reveals that 67% of startups in their early stages opt for incorporation in Delaware.[136]

Now, let’s shift our focus to our exploration of unicorns.

C. New Unicorn Data

Employing empirical analysis supported by hand-collected data on unicorns’ incorporation and headquarter choices, the study below delves into private company charter competition in the United States. By doing so, it contributes to an enhanced scholarly understanding of the market for corporate law.[138] Contrary to the prevailing perspective that privately held corporations typically choose to incorporate in the state where their primary business operations are situated, this Article challenges and refutes that notion.

To validate my hypothesis, suggesting that a heightened presence of out-of-state investors and the adoption of the NVCA’s model charter documents by prominent law firms are associated with a greater probability of unicorns incorporating in Delaware, I examine data from a specifically chosen sample of unicorn companies. This section provides an overview of my dataset and offers summary statistics related to the incorporation status of unicorn firms within the sampled cohort.

1. Data Collection.

In an effort to gain deeper insights into the global landscape of privately held innovation driven firms, particularly those decorated with the desirable “unicorn” status, I embarked on a comprehensive hand extraction of information from different platforms, including PitchBook and various departments of state divisions of corporation. I collected information related to registered businesses, corporate entities, entity names and types, incorporation details, and related filings. The primary focus of this research was to unveil the geographical distribution of these high-valued startups, shedding light on both their headquarters and the jurisdictions where they are officially incorporated or reincorporated. It’s important to note that the accuracy and availability of specific data points may vary depending on the level of disclosure by the unicorn firm and the stage of development.

a. Research Design. Data was obtained from PitchBook’s Unicorn Tracker until the year 2021. PitchBook’s unicorn tracker contains all new unicorn companies formed since the beginning of 2016. It provides a list of all unicorns that are created in a given year in that time period.[139]

The data is limited to U.S.-based unicorn companies. The research involves a cross-sectional examination of the unicorn firms’ incorporation and headquarters locations. Subsequently, the date of incorporation and headquarters location information were extracted from public data sources for each firm. I retrieved information on the date and location of incorporation utilizing Delaware’s Department of State, Division of Corporations. I matched, verified, and compared data on headquarters’ location using public data from Delaware’s Department of State and other states department of state websites. The following variables were relevant:

-

Independent Variable: Date of incorporation, value of corporation above $1 billion.

-

Dependent Variables: Location of incorporation, location of headquarters.

The data collection process involved extracting pertinent information from the following sources:

i. Pitchbook. Pitchbook is a financial data and software company that specializes in collecting and providing information on private market transactions, including data on unicorn firms. PitchBook’s extensive database is a source renowned for its thorough coverage of private market transactions.[140] Specifically, the dataset encompassed details on unicorn startups, defined as privately held companies with valuations surpassing the $1 billion threshold. Key variables included the startup’s name, current valuation, funding history, executive leadership, and, crucially, its geographic locations for headquarters and incorporation.

ii. Departments of State Divisions of Corporation. Corporate law varies by state. I accessed data from Departments of State Divisions of Corporation, from the following states: Delaware, New York, California, Nevada, Wyoming, Maryland, and North Carolina. The date collection on business incorporations involved navigating the respective government agencies responsible for overseeing corporate registrations. The common data points collected on business incorporations included entity names, dates of formation, and types of entity.

2. Methodology

The methodology employed was descriptive statistics to analyze the distribution of unicorns based on their date of incorporation, location of incorporation, and location of headquarters. It involved a systematic process of gathering, organizing, and analyzing information to address the specific research question—where are unicorns incorporated and headquartered?

For each company included in my sample, I gathered information on the initial state of incorporation. I compared it with research on both public firms by Daines (2002), Bebchuk and Cohen (2003) and private firms by Dammann and Schündeln (2011) and Fried, Broughman, and Ibrahim (2014). My findings indicate that unicorn firms will face a binary decision, opting to incorporate either in their home state or in Delaware.

The following provides descriptive statistics for the 220 firms in my sample.

a. Pitchbook. By navigating through PitchBook’s rich repository of private market data, I compiled a comprehensive list of unicorn startups, capturing key details on each entity, specifically, where the entity was founded and where is it headquartered. The data extraction process involved cross-referencing multiple sources to ensure accuracy and completeness, mitigating the risk of overlooking critical information.

b. Departments of State Divisions of Corporation. By navigating through the states’ rich repository of divisions of corporation databases, I searched for entity names, dates of formation, and types of entity. The data extraction process involved cross-referencing the results with other states’ divisions of corporations and sources to ensure accuracy and completeness, mitigating the risk of overlooking critical information.

3. Key Insights and Results.

The study aims to present a comprehensive overview of the distribution of American unicorn companies based on their date of incorporation, location of incorporation, and location of headquarters. The dataset used included 220 U.S.-based unicorns.

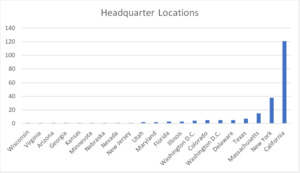

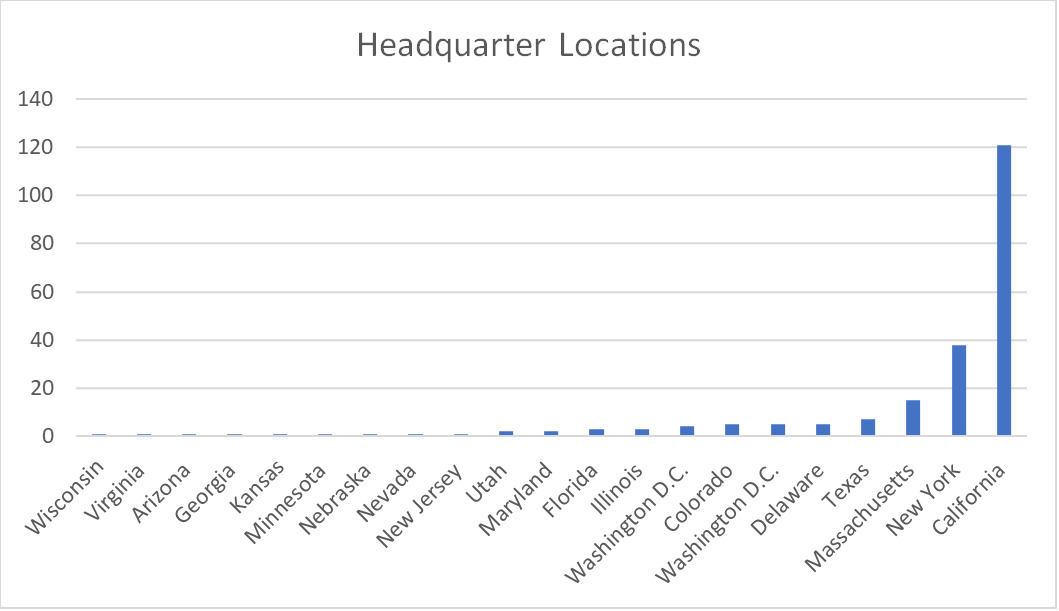

The chosen state of incorporation has remained extremely consistent, with only 5 out of the 220 unicorns in my data not incorporating in Delaware. Meanwhile, the headquarter locations, while less predictable based on the data, indicate a preference for California.

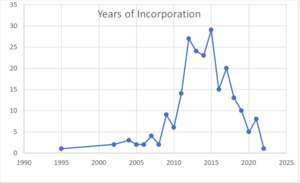

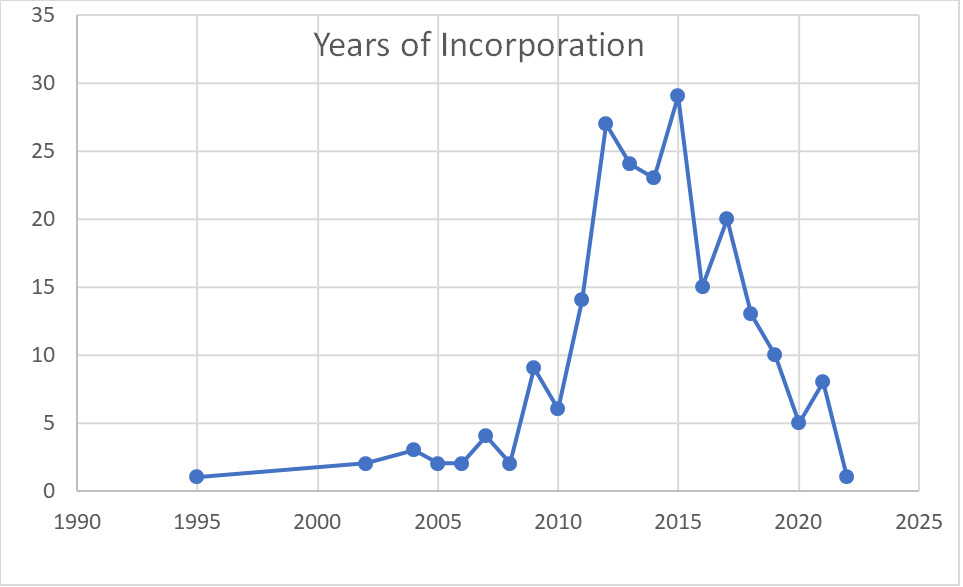

In Table 1, I have data on the years of incorporation, the incorporation locations, and the headquarter locations for 220 of these companies. Based on a sample of 220 firms, the number of U.S. unicorns per year increased noticeably from 2010–2015 and has since begun dropping again.

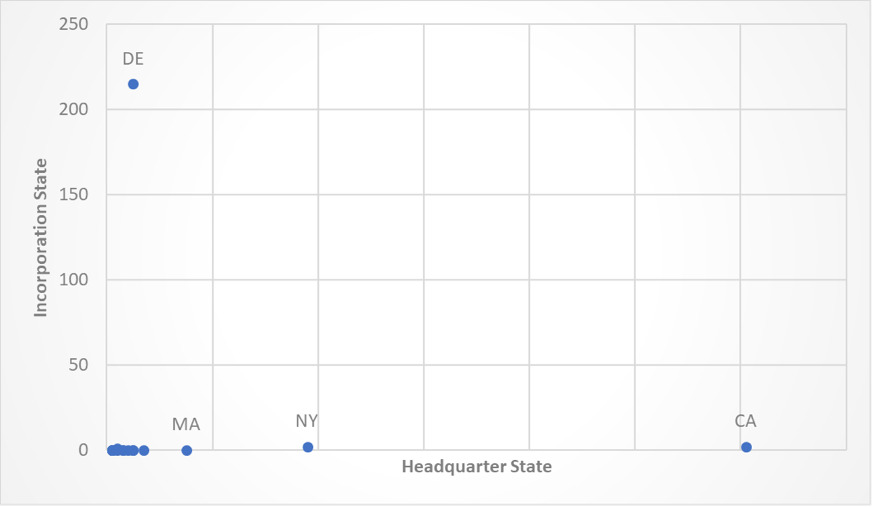

In Table 2, the collected data revealed that roughly 97% of the unicorns in the dataset are incorporated in Delaware. Out of the 220 unicorns in the sample, a significant majority—215 firms—chose Delaware. Only five firms made a different choice, with two selecting California, and two opting for New York, and surprisingly, one choosing Maryland. This data underscores Delaware’s predominant status as the preferred incorporation destination for unicorn firms within the U.S. startup ecosystem.

In Table 3, the collected data revealed a nuanced picture of the national distribution of unicorn startups. Geographical patterns emerged, showcasing concentrations of these high-value entities in particular regions in the United States.

A scatter plot illustrates the relationship between the state of incorporation and the headquarters’ location with the prominent outliers labeled.

By juxtaposing the headquarters and incorporation locations, it became possible to discern strategic decisions made by these startups, their investors and lawyers in selecting their operational and legal bases.

4. Implications

The findings of this research hold implications for various stakeholders, including investors, policymakers, and industry analysts. Understanding the geographical preferences of unicorn startups may provide a valuable framework for investment strategies, regulatory considerations, and regional economic assessments.

Despite these general trends, there may be a suggestion that unicorn firms are distinguished from typical startups, and therefore, may exhibit different behavior in their choice of incorporation state.

5. Challenges and Limitations.

While the data collection process was thorough, there are always potential challenges and limitations. Some startups may operate in stealth mode or disclose limited information, which impacts the comprehensiveness of the dataset. Additionally, data may be subject to change due to dynamic business environments, funding events, or corporate restructuring.

Limitations include the reliance on publicly available data and potential discrepancies between official records and the information available on PitchBook. Due to ethical considerations, the data involved is publicly available. No identifiable personal information is utilized, and the study adheres to privacy regulations.

6. Additional Data

a. Extended Time to Exit. Unicorns are staying private for longer periods as noted above. Their strategy aligns with a broader trend in the startup ecosystem. Unicorns are different from other startup firms because they deliberately choose to delay IPOs (or other exits) and remain private to navigate business challenges, maintain control, and optimize their growth strategies without the immediate pressures of public markets.[141]

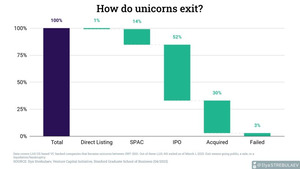

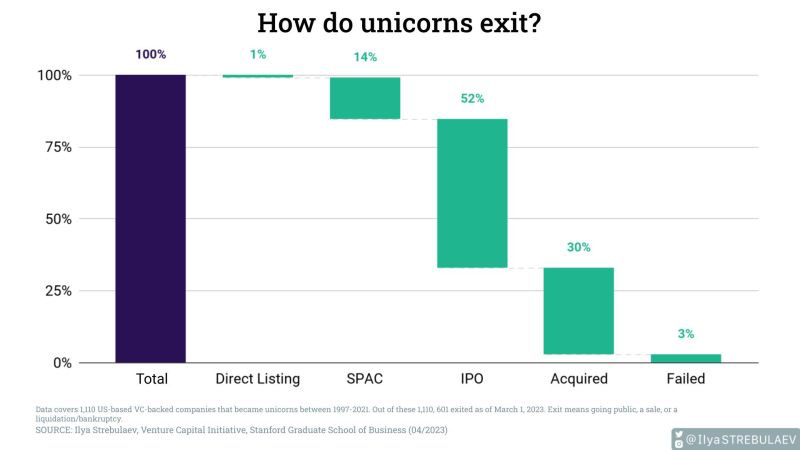

To illustrate these claims, I’m building on Strebulaev’s research. Strebulaev conducted a study on 1,110 U.S.-based VC-backed unicorns. His study focused on their exit strategies, where the definition of an exit event encompasses public listing, acquisition, bankruptcy, or liquidation. [142] He found that unicorns are delaying their exits and are staying private longer. As of March 1, 2023, 601 companies, constituting 54% of the total, had exited the market.[143]

The most common exit route for unicorns was through an IPO, with 311 companies, or 52%, opting for this method. Another notable trend was going public via a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC). Eighty-six unicorns, accounting for 14%, chose this method, with examples such as Offerpad, Heliogen, and BARKBOX, INC.[144] A smaller subset of six unicorns, equivalent to around 1%, chose a direct public listing for their exit strategy. Examples of companies employing this method include Asana, Squarespace, and Roblox.[145]

Approximately 30% of unicorns, totaling 180 companies, opted for acquisition by other entities, including other companies and private equity funds. Examples of such acquisitions include Salesloft, Indeed, and Headspace.[146] “Finally, 18 companies, or 3% of all exited unicorns” faced outright failure through bankruptcy or closure.[147] Examples of these cases include BlockFi and Celsius Network, emphasizing that startups may also encounter challenges in ways beyond traditional exit strategies, such as being acquired at a lower valuation.[148]

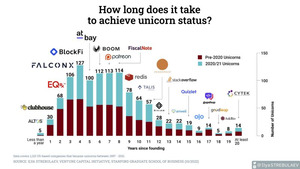

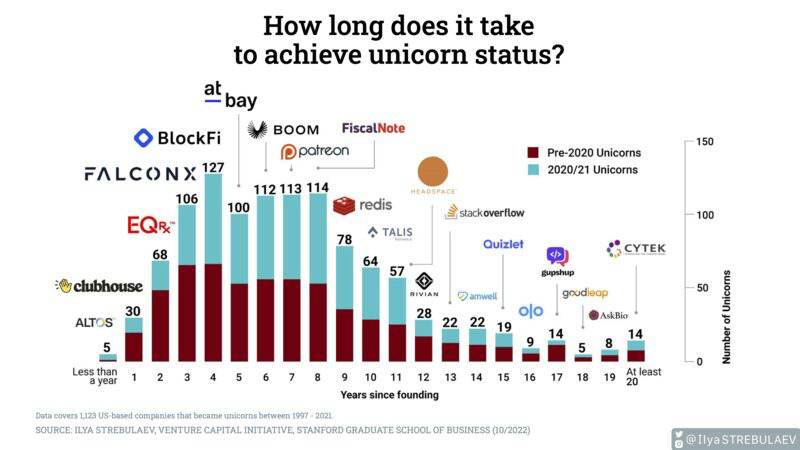

b. Time to Get to Unicorn Status. How long does it take for a privately held firm to achieve unicorn status? In Strebulaev’s examination of the time it takes for companies to achieve unicorn status, he found that the median unicorn in his sample of 1,123 companies took seven years from founding to attain a valuation of $1 billion or more.[150] Notable companies such as Tesla, SentinelOne, and Affinivax Inc. align with this profile.[151]

Interestingly, the most recent unicorns, entering the sample in 2020 and 2021, took, on average, a comparable number of years to achieve unicorn status as those that became unicorns prior to 2020.[152] This indicates a consistent trend across different time periods. However, there is substantial variability among unicorns, with three out of four companies achieving unicorn status within nine years of their founding.[153]

Some companies achieved unicorn status very rapidly—Altos Labs in about a year, and EQRx in about two years.[154] In contrast, others took significantly longer, such as Quizlet, which took fifteen years, and Cytek Biosciences, which took twenty-eight years.[155] These results suggest that the growth trajectory is highly company-specific. Unlike Strebulaev, I feel that the influence of market conditions is also an important factor to consider in determining the time it takes for a company to achieve unicorn status.

IV. Delaware’s Influence on Corporate Governance

Delaware stands as the preferred state for incorporation among numerous firms in the United States and globally, irrespective of their size.[157] When it comes to unicorns, this study utilizing meticulously gathered data from diverse filings reveals a staggering statistic—97% of unicorn firms in the United States opt for incorporation in Delaware. This underscores the significance of any Delaware court decision on this matter, as it will wield influence over the rights of hundreds of thousands of unicorn employees across the United States.

A. Delaware’s Dominance in the Unicorn Race

The data and this Article add to the ongoing discussion about whether there is a race to the top or a race to the bottom. These findings, the deliberate choice of 97% of unicorns to incorporate in Delaware, indicate a trend favoring the race-to-the-top theory. This absolute preference suggests that Delaware’s legal framework is perceived as advantageous for the investors, who are shareholders, which means that Delaware law is perceived by sophisticated investors as serving their needs, i.e., being friendly to shareholders rather than management.

1. Sophisticated Investors.

It’s crucial to note that unicorns attract sophisticated investors, not retail investors, reinforcing the notion that Delaware’s legal framework is tailored to the needs of experienced and knowledgeable investment entities.[158] The distinction in investor composition between unicorns and public companies is crucial. Unicorns, attracting sophisticated investors rather than retail ones, align with Delaware’s legal framework that caters to experienced and knowledgeable investment entities. This nuanced investor landscape significantly influences the corporate structure and governance of unicorns, underscoring the need for specific considerations in comprehending and regulating their unique dynamics.

Moreover, unicorns also deviate significantly from other privately held startups due to their reluctance to go public. [159] This distinctive trait shifts the focus of unicorn shareholders towards enforcing contractual rights rather than anticipating an IPO or other exit mechanism in the near future. To illustrate the preference of sophisticated investors for Delaware incorporation, consider the example of the NVCA, a trade association representing the U.S. venture capital industry.[160]

2. The National Venture Capital Association.

A major NVCA initiative involves creating standardized legal documents for venture capital transactions, streamlining the investment process. These documents, widely accepted in the industry, serve as benchmarks, minimizing obstacles and expediting startup funding. It recommends Delaware as a venue in its deal documents because of the state’s favorable legal environment and predictable corporate laws.[161]

To illustrate, see the example of funding for startups. The NVCA collaborates with legal professionals to develop these documents, including the Certificate of Incorporation (COI), a crucial document defining stock rights. In 2015, the NVCA designated Delaware as the preferred forum in COIs, establishing it as the industry norm.[162] This standardization aims to enhance efficiency and transparency in negotiations, benefiting both investors and entrepreneurs.[163]

The NVCA’s adoption of Delaware in its model deal documents is also a strategic choice that underscores the recognition of Delaware’s regulatory regime, known for offering superior corporate governance and reliability, as particularly well-suited for the distinctive needs and complexities of privately held firms. The NVCA represents venture capitalists and the venture capital industry in the United States. It is a trade association advocating for public policy that supports these institutional investors and startup companies, and so they chose a state that will benefit the interests of these groups.[164]

Unfortunately, recently, the Moelis decision by the Delaware courts has raised significant concern among lawyers representing the venture capital industry, prompting them to critique Delaware courts over the ruling.[165] They claim that this decision impacts the enforceability of shareholder rights provisions, introducing uncertainty, shifting the balance of power, and complicating the drafting of agreements—critical issues for venture-backed startups.[166] Consequently, the venture capital industry reconsidered its reliance on Delaware for incorporation and adopted new strategies to safeguard its interests.[167]

B. Venture Capital Lawyers’ Critique of Delaware Courts Over the Moelis Decision

“On February 23, 2024, the Delaware Court of Chancery issued its decision in West Palm Beach Firefighters’ Pension Fund v. Moelis & Company, which invalidated a stockholder agreement between Moelis . . . and its founder and controlling shareholder, Ken Moelis.”[168] The decision drew immediate criticism from the venture capital industry and the members of the Delaware bar,[169] who described it as having “shaken up the existing state of the governance and management of Delaware corporations.”[170]

1. Revolting Against Delaware Courts

The decision revolves around the enforcement of certain shareholder rights provisions, which are perceived by these critics as crucial for maintaining the balance of power in venture-backed startups.[171] The lawyers’ critique is rooted in the perceived impact of the Moelis decision on the drafting and enforcement of these provisions. They argued that this uncertainty undermined the predictability that Delaware’s legal system is known for.[172] For venture-backed startups, predictability is crucial in attracting investment, as it reassures investors that their rights and interests will be protected.[173]

“In response, the Corporation Law Council of the Delaware State Bar Association drafted a proposed amendment [to create] § 122(18) of the Delaware General Corporation Law (the ‘Proposal’). The Proposal was [included in] a package of amendments submitted to the Delaware legislature on May 23, 2024.”[174] The legislature adopted the proposal and overturned the Moelis decision in its entirety, less than six months after the opinion was issued and before any review by the Delaware Supreme Court.[175]

This move potentially shifts the balance of power between different classes of shareholders, especially in scenarios where they are minority stakeholders. Venture capitalists often negotiate for certain rights and protections to safeguard their investments.[176] This move by the legislature is tilting the balance of power in favor of majority shareholders or founders. This can potentially increase the legal costs and time involved in structuring future deals.

2. Strategic Implications for Minority Shareholders

The critique of Delaware courts over the Moelis decision and the actions of the Delaware Legislature signals a re-evaluation of Delaware as the preferred jurisdiction for incorporation. While Delaware’s legal system has historically been favored for its clarity and pro-business stance, these actions might prompt minority shareholders to consider alternative jurisdictions that offer more predictable enforcement of minority shareholder rights.

It will likely increase the risk of litigation. Disputes over the interpretation and enforcement of shareholder rights provisions may become more common, leading to higher legal costs and potential delays in business operations and exits.

Minority shareholders and their legal representatives may need to adopt more aggressive negotiation tactics to secure the necessary protections. This could involve seeking more explicit and detailed contractual language or negotiating for additional covenants and assurances from founders and majority shareholders. The following section explains why and how this move will impact the most vulnerable minority shareholders—employees.

C. Employees as Common Shareholders and Stock-Option Holders

Most investors that allocate financial or human capital to private firms in private markets inevitably confront the issues of “agency cost”[177] and “information asymmetry.”[178] The recent regulatory changes to our securities laws, as outlined below, were enacted with the assumption that company employees should be regarded as potential common shareholders and, as insiders, possess intimate knowledge of the business. Consequently, it was presumed that they might not require the safeguards of mandatory disclosure. However, this presumption is less likely to hold true for unicorns. For instance, employees within unicorn firms are probably unable to fully grasp how the preferences granted to venture capital investors can lead to the dilution of the value of their common stock holdings.

1. Employee Participation as Investors.

The concept of employees as investors in tech firms revolves around the idea that employees contribute their human capital, i.e., their labor, intellectual capital, and skills to the company, in return for the promise of equity. It is detailed in my work on Unicorn Stock Options,[179] Alternative Venture Capital[180] and Bargaining Inequality.[181]

The following explains how employees receive compensation and equity, while playing a crucial role in the firm’s innovation, growth, and overall success. Employees in the tech industry often receive additional incentives in the form of equity, stock options, or other ownership stakes in the company.[182] This makes them more than just workers; they become shareholders, stock-option holders, and stakeholders with a vested interest in the company’s performance and future.

Employees are repeat players.[183] In the context of their employment within a company, employees engage in repeated interactions with their employer over an extended period. This concept emphasizes the ongoing, continuous nature of the employment relationship. Employees are not involved in isolated, one-off interactions; rather, they are integral and consistent contributors to the functioning and success of the organization. As repeat players, employees build a cumulative understanding of the company’s culture, operations, and objectives through continuous involvement, making them valuable assets with a deeper understanding of the business dynamics.

By holding equity or stock options, employees essentially also become investors in the success of the company.[184] Their compensation is tied to the company’s valuation, and they stand to benefit if the company performs well, often gaining a share in its financial success.[185] This aligns the interests of employees with those of traditional investors, fostering a sense of ownership, loyalty, and motivation to contribute to the company’s growth and profitability.[186]

In essence, employees as investors in tech firms highlights the multifaceted relationship between the workforce and the company, where employees not only provide their labor but also have a financial stake in the organization’s prosperity.

The problem is, however, that employees often lack sophistication compared to represented investors, and often find themselves at a disadvantage due to a new exploitation of equity award information asymmetry within startup environments. This exploitation takes the form of a waiver of inspection rights.

This contractual waiver is particularly detrimental to minority common stockholders or stock-option holders, such as employees, who, despite their lack of representation, must make crucial investment decisions, like exercising their stock or leaving to compete with the firm.[187] As employees constitute minority shareholders, serious agency problems arise, coupled with conflicts of interest between majority and minority common shareholders, now posing challenges to the corporate governance system in unicorn firms.[188]

2. Evolution and Historical Context of Equity Compensation.

Historically, startup founders and rank-and-file employees belonged to the same class of common shareholders, aligning their incentives.[189] However, contemporary market changes and investments from alternative and venture capital investors have allowed founders of unicorn firms to negotiate more powerful contractual arrangements.[190] This includes the ability to control the board of directors through super voting rights and other arrangements detailed in my work on Unicorn Stock Options and Alternative Venture Capital.[191] Consequently, these new arrangements amplify the power of founders within the firm at the expense of other employees, leading to misalignment of interests between employees and founders as common shareholders.

The decision of unicorn founders to remain private is motivated by a desire to exert greater control over the firm, safeguard proprietary information, and prevent leaks to competitors.[192] Additionally, founders have a vested interest in avoiding the substantial costs associated with employee turnover, particularly given the high demand and shortage of skilled tech labor globally. Tech companies strategically limit information leakage to maintain market power, dominance, and hinder competition, consequently raising barriers to entry for smaller firms.[193] Key tech regions in the United States, such as Silicon Valley and Route 128 in Boston, owe their success to factors like robust investment in research and development, government funding, strong links between academia and industry, well-established risk-capital networks, and specialized infrastructure like law firms.[194] This success is further fortified by a strict code of secrecy, supported by urban legends about retribution for employees who violate this code.[195]

D. Delineating the Impact of Securities Law Amendments on Delaware’s Corporate Landscape

Moreover, the recent changes in U.S. securities laws have further complicated the scenario, as employees no longer receive the information they used to, contributing to heightened information asymmetry and potentially leaving common shareholders, particularly employees, more vulnerable in this evolving landscape.[196]

Originally, U.S. securities laws were crafted with the intention of safeguarding all investors, including employees who serve as investors in a company.[197] This meant that every company in the United States was obligated to divulge financial and other pertinent information about the offering firm before issuing securities to the public.[198] Specifically outlined in the Securities Act of 1933 (Securities Act), these laws mandated that a company seeking to sell its securities must first register them with the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC).[199] Throughout the registration process, the issuing company was required to disclose various details, including certified financial statements, a comprehensive description of its assets, and business operations, management composition, and other relevant information.[200]

E. Shifts in Common Shareholder Dynamics: Evolution and Impact on Delaware’s Corporate Realm

Delaware law holds particular significance in the context of the following shifts in governance, brought about by transformative changes in the startup funding model and the governance structures of VC-backed firms, especially as orchestrated by unicorn founders.[201] Departing from historical norms, founders are increasingly inclined to prolong the period of staying private, thus retaining significant control over the firm. This notable trend is underpinned by the emergence of founder-friendly financing rounds within the venture capital investment landscape, introducing considerable alterations to the dynamics of senior management and the distribution of employee equity.[202]

Not all common shareholders are the same; in fact, the interests of founders and senior management as common shareholders have diverged from those of rank-and-file employees in the contemporary startup landscape. In the earlier paradigm, both senior managers and employees commonly received common stock, a practice maintained by VC-backed startups issuing two classes of stock: common and preferred.[203] However, a notable shift has occurred, with unicorn founders now exerting greater negotiating leverage over venture capital investors, particularly in matters pertaining to economic, liquidity, and voting rights.[204] What was once considered an improbable scenario—privately-owned startups achieving valuations surpassing $1 billion without going public—has now become commonplace, exemplified by the current classification of hundreds of companies as “unicorn” firms.[205]

The proliferation of unicorn firms persists, undeterred by the current challenges posed by elevated interest rates, thanks to sustained investor interest. Founder-friendly terms, initially introduced during market booms,[206] have endured and continue to shape the startup landscape.[207] A notable development in these terms is the introduction and retention of founder super-voting stock. This unique structure involves two types of common stock, Classes A and B. Class B, allocated to founders, carries multiple votes per share (e.g., ten to twenty multiples), ensuring control over the company even in the face of dilution in subsequent financing rounds.[208] On the other hand, Class A, featuring a single vote per share, is designated for issuance under the unicorn’s stock option plan, benefiting rank-and-file employees. This innovative framework is strategically designed to uphold founder control amidst the evolving dynamics of financing and equity distribution.[209]

F. Evaluating Delaware’s Role in Safeguarding Employee Shareholder Interests

Delaware courts bear a distinctive responsibility concerning unicorn firms. Given that these firms are not obliged to disclose information to the public, common shareholders, such as employees, lack inside information on the company’s operations, and their protection is limited contractually.[210]

Delaware law plays a crucial role in providing companies with the necessary clarity to avoid potential litigation with employees through meticulous planning and transparent contractual arrangements.[211] Section 220 of the Delaware General Corporation Law (DGCL) stands as a safeguard for shareholders, granting them the authority to exercise their ownership rights by inspecting the books and records of a Delaware corporation.[212] Importantly, in Delaware, this fundamental ownership right cannot be nullified or restricted by any provision in a corporation’s COI or bylaws.[213] Despite the protective measures afforded by Section 220, there exists a degree of ambiguity in current case law regarding contractual arrangements and the concept of private ordering.[214]

Commonly, employees now waive their inspection rights through contracts, further highlighting the significance of Delaware courts in addressing the unique challenges faced by unicorn firms and their common shareholders.[215]

The following is an explanation on the importance of information rights.

1. Addressing Information Asymmetry Challenges for Employee Investors in Private Companies.

Decision-making processes are profoundly influenced by information and knowledge across personal, professional, and organizational contexts.[216] This significance is particularly pronounced in private market investments, which inherently carry risks and grapple with information asymmetry. Information asymmetry arises when one party involved in a transaction possesses more information about the subject than the other party.[217]