I. Introduction

The Trademark Modernization Act of 2020 (TMA)[1] made three substantial changes to the trademark system of the United States. The first was to codify a presumption that infringement of a trademark causes irreparable harm[2]—putting a heavy thumb on the scale of the equitable analysis of injunctive relief set forth by the Supreme Court in eBay v. MercExchange.[3] The second was to provide a technical fix to the statutory authority of the Director of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO),[4] to ensure that the USPTO’s adjudicative processes would not run afoul of innovations in the Supreme Court’s Appointments Clause jurisprudence.[5] The third, which is the subject of this Article, was to provide new tools to purge the principal trademark register of “clutter”—registrations for trademarks that are either not used at all by their registrants, or not used on the full array of goods and services claimed in a registration.[6]

It is generally accepted that the registration (and maintenance of registration) of trademarks that are not actually used by their registrants imposes substantial costs on the public.[7] Such registrations raise trademark clearance costs, impose chilling effects on competitors, and deprive the marketplace of potentially useful and valuable source identifiers.[8] And there is substantial evidence of clutter on the federal principal register maintained by the USPTO. Since 2017, the Office has conducted random audits of recently renewed trademark registrations claiming use of the registered mark in connection with four or more types of goods or services.[9] Roughly half of the over 29,000 registrations audited through the end of 2023 ended up deleting at least one listed good or service from the registration because the registrant could not establish that they were using the mark in connection with that good or service, and approximately 13% were cancelled entirely (presumably because the registrant, while seeking renewal, was no longer using the mark at all).[10]

Moreover, this problem of clutter is believed to be increasing lately due to several factors extrinsic to the register itself. First, certain regional government offices in China had offered bounties to firms and individuals who obtained intellectual property rights abroad, and the bounties apparently exceeded the fees necessary to obtain such rights. Indeed, these bounties were reportedly sufficiently substantial as to induce large numbers of Chinese applicants to seek registrations of trademarks in the United States that they had no intention of using in the United States, simply to establish a right to the bounty.[11] That problem seems to have abated, as sub-national Chinese government authorities have largely withdrawn the offending subsidies.[12] Second, the rise of the Amazon e-commerce marketplace, and Amazon’s use of trademark registrations as a means of providing favorable treatment to registrants in listing their products on Amazon and in disputing Amazon product listings posted by their competitors, is argued by some commentators to have substantially increased the volume of applications to register trademarks that do not actually serve as source identifiers—again, particularly by Chinese firms and nationals.[13] This trend seems to have been exacerbated by the sudden heavy increase in e-commerce usage during the lockdowns of the COVID pandemic.[14] In addition to imposing increasing administrative burdens on the USPTO, these spurious registrations allow their owners to obtain benefits on e-commerce platforms that prioritize placement and sanction unfair practices via automated or algorithmic processes, in ways that may put legitimate trademark users and other competing sellers at an unfair competitive disadvantage that can be difficult to overcome.[15] In both contexts, applicants for registration appear to be falsifying their evidence of use in commerce—a prerequisite for trademark registration—at alarming rates, and thereby causing substantial economic harm.

As one means of addressing this problem, the TMA has created two new forms of administrative proceedings designed to clear such spurious marks from the register. The new expungement proceeding, codified in the new § 16a of the Lanham Act, allows for the total expungement of a registration “on the basis that the mark has never been used in commerce on or in connection with some or all of the goods or services recited in the registration.”[16] Additionally, the new reexamination proceeding, codified in the new § 16b of the Lanham Act, allows for the total or partial cancellation of a registration “on the basis that the mark was not in use in commerce on or in connection with some or all of the goods or services recited in the registration on or before the relevant date,” that date being the date on which the applicant submitted a sworn statement of use in commerce.[17] Both expungement and reexamination proceedings may be instituted by petition (subject to the USPTO’s decision to institute a proceeding upon the petition), or by initiative of the Director of the USPTO; after the registrant is given an opportunity to respond in writing, the proceedings are resolved by the USPTO ex parte.[18]

Congress’s hope for these new proceedings was that they would “respond to concerns that registrations persist on the trademark register despite a registrant not having made proper use of the mark covered by the registration” by “allow[ing] for more efficient, and less costly and time consuming alternatives to inter partes cancellation.”[19] Cancellation proceedings “in many respects . . . resemble district court litigation [in that] they are often expensive and time consuming[, and therefore,] [f]or small- and medium-sized businesses, the cost of filing and the uncertainty of the result is often a deterrent.”[20] By giving interested third parties a cheaper, faster process to identify clutter on the register and prompt the USPTO to clear it through ex parte processes, the new expungement and reexamination proceedings were expected to help address the deluge of spurious unused registrations that threatened the reliability and usefulness of the trademark registration system.

The expungement and reexamination provisions of the TMA became effective in December of 2021,[21] so we now have over two years of experience with them against which we can judge their effects. As I will explain in this Article, empirical evidence from those first two years suggests that they have had at most a marginal effect on spurious applications. Expungement and reexamination petitions are seldom filed, proceedings on those petitions are only sometimes instituted, the number of proceedings initiated by the USPTO sua sponte is relatively small, and the time it takes to proceed from institution of a proceeding to a cancellation order is substantial.[22] In a system where random audits of the most recently maintained registrations suggest an overall nonuse rate of between 10% and 50%,[23] the machinery of third-party petitions and ex parte review appear to be a particularly inefficient means of identifying and clearing clutter on the trademark register.

But perhaps identifying clutter is not these proceedings’ primary function. While the machinery of TMA proceedings has been standing up, the USPTO has also undertaken a number of separate administrative measures to attempt to stem the tide of spurious applications and renewals. In addition to the above-mentioned auditing program, the USPTO has required all foreign trademark registration applicants to be represented by domestic counsel;[24] it has required all electronic trademark registration applicants to register for an online account with two-factor authentication,[25] and it has required all such applicant accounts to submit to identity verification.[26] These administrative measures seek to stem the tide of spurious applications ex ante, as contrasted with the ex post review of registrations that may have erroneously issued that the new TMA proceedings make possible. Along the way, the USPTO also substantially raised application fees, and created a new fee for removing goods and services from a registration after applying to renew that registration.[27] As it turns out, these administrative measures seem to correlate with changes in application volume that far exceed the total number of TMA proceedings initiated since those proceedings became available.

Based on the analysis presented herein, the primary benefit of the TMA’s new proceedings may simply be that they provide a ready vehicle for registrations that are already known to be vulnerable for lack of use—but which somehow cleared the increasing barriers to spurious applications—to be flagged for USPTO review. While a mechanism for formally removing registrations that have already been identified by interested third parties as spurious is obviously useful, it does not appear to shift the cost of clutter away from those third parties, let alone impose those costs on the parties who created the clutter in the first place. Nor does it seem to add much to the authority already asserted by the USPTO in its auditing program to demand that registrants supply proof of their continued use of their marks on the goods or services claimed in their registrations.[28] Preventing spurious applications from being filed in the first place would seem to be a much more equitable and efficient strategy for avoiding clutter, though doing so might also raise costs to legitimate applicants, and perhaps to the USPTO as well. A review of these various policy interventions thus reveals the problem of clutter to be symptomatic of the increasing automation of our legal and social institutions—a degree of automation that makes it difficult if not impossible to enforce fact-sensitive standards at scale, and imposes subtle but inescapable new burdens on everyone who relies on those institutions.

II. Data and Methods

This Article reports an original dataset of all TMA proceedings filed to date. The dataset is collected from three sources: (1) the USPTO’s online “Trademark Decisions and Proceedings” page,[29] (2) the USPTO’s Trademark Case Files research dataset,[30] and (3) records of trademark registration case files on the USPTO’s “Trademark Status & Document Retrieval” service (TSDR)[31] for registrations that are identified in the “Trademark Decisions and Proceedings” page as having been the subject of an expungement or reexamination proceeding.[32] A detailed description of this dataset is set forth in the Appendix at the end of this Article.

Using this data, I report in Sections III.A and III.B below descriptive statistics of various measures of TMA proceedings’ characteristics of interest, such as the number of proceedings filed, their success rate, and their average pendency, further broken down by various indicators such as registrant nationality, filing basis, type of proceeding, and whether the proceeding was initiated upon a petition or upon the USPTO’s own initiative.[33] But perhaps the most important finding in this analysis is the miniscule absolute number of petitions for TMA proceedings relative to the total number of registrations likely to be susceptible to such petitions.

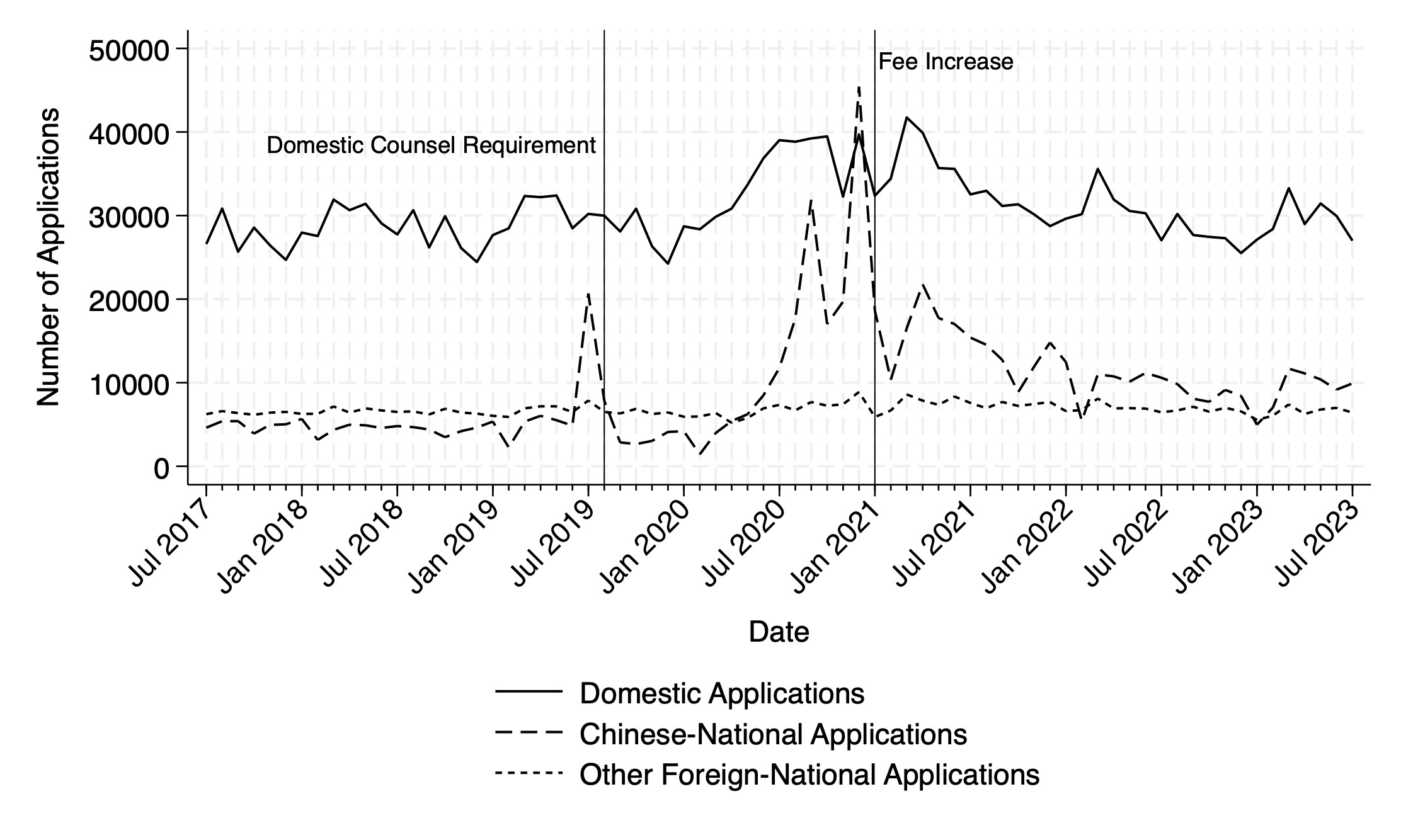

To compare the effect of TMA proceedings on clutter to the effect of the USPTO’s non-statutory interventions in screening applications (particularly foreign applications), in Section III.B I use data derived from the USPTO’s Trademark Case Files Dataset to generate an illustration of the interaction between those interventions and both foreign and domestic application rates, with particular attention to applications owned by Chinese nationals. Charting application volumes against the dates of two of the USPTO’s administrative interventions—the domestic counsel requirement and the increase in application fees—suggests that those interventions substantially influenced the behavior of Chinese-national applicants while having a far less substantial effect on domestic applicants and on other foreign applicants.[34]

III. Analysis

As noted above, TMA proceedings vary according to several criteria. They may be expungement proceedings—relevant where a mark is alleged never to have been used on certain goods or services listed in the registration—or reexamination proceedings—relevant where the registrant may have used the mark, but only after the date they swore to the USPTO that they had done so in order to obtain their registration.[35] They may be initiated by a petition filed by an interested party or by the USPTO on its own initiative.[36] The registrations subject to such proceedings also vary according to various relevant criteria: their age, their renewal history, the nationality of their owners, and their filing bases,[37] for example. Any analysis of these proceedings will necessarily take interest in their outcomes: whether a petition led to institution of a proceeding, the pendency of the petition prior to rejection or institution of the proceeding, whether the registrant responded to either the petition or the institution of a proceeding, whether the registrant voluntarily cancelled their registration in whole or in part, and whether the USPTO ultimately cancelled the registration in whole or in part. This part will report descriptive statistics on several of these areas of interest.

A. Initiation of TMA Proceedings

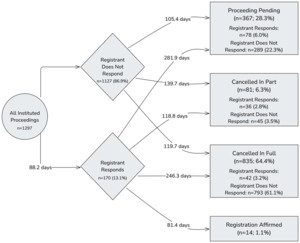

There were 1,528 TMA proceedings docketed between the effective date of the TMA in December of 2021 and the close of this Article’s data collection period on September 7, 2024. Of these, 274 are expungement proceedings and 1,254 are reexamination proceedings. Some trademark registrations have been the subject of multiple TMA proceedings: 156 registrations have had two proceedings docketed against them, and 21 registrations have had three proceedings docketed against them.

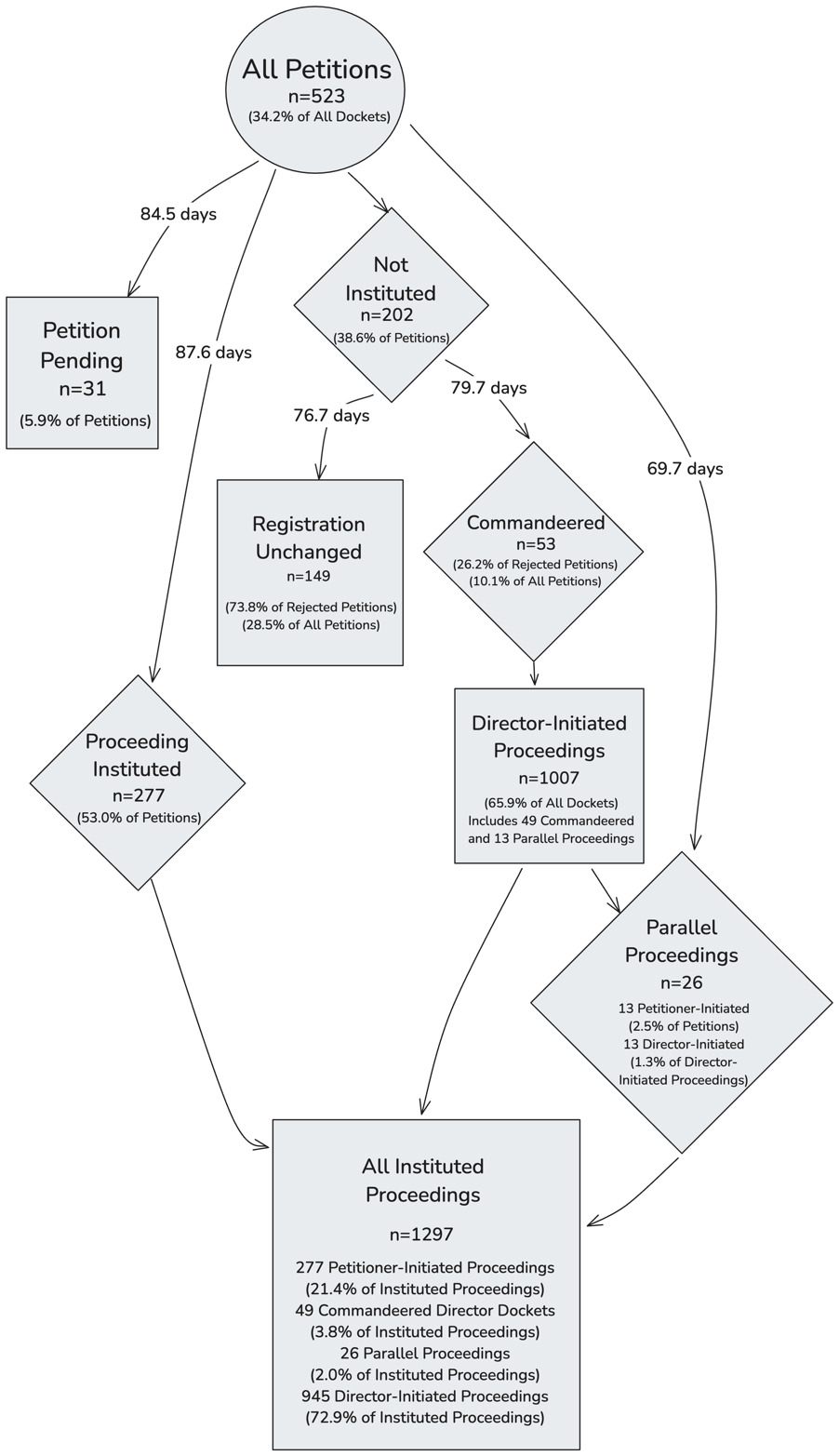

We can begin to further understand how these proceedings are affecting the trademark registration system by examining the circumstances of their initiation:

As Table 1 shows, the USPTO has itself either initiated or “commandeered” approximately two-thirds of all TMA proceedings to date, most of them reexamination proceedings. By “commandeered,” I refer to a surprisingly common situation in which the USPTO declines to institute a proceeding upon a petition, but then institutes a proceeding against the same registration on its own initiative.[38] This mechanism appears to be used primarily where a petition fails to comply with all formal or substantive requirements of the TMA or applicable USPTO rules,[39] or otherwise fails to provide an evidentiary basis for expungement or reexamination. For example, the USPTO declined to institute a reexamination of Registration No. 7,159,298 in response to a petition, on grounds that the petitioner “fail[ed] to set forth a prima facie case because the investigation related to use was not appropriately comprehensive . . . [because that investigation] did not include a review of the appropriate trade channels related to the goods during the relevant time period subject to the petition.”[40] But on the very same day it rejected the petition for reexamination, the USPTO instituted a reexamination proceeding on its own initiative, apparently based on its own investigation undertaken to cure the infirmities of the petitioner’s evidence.[41] As Table 1 shows, this pattern (or something similar) has repeated itself over fifty times in the first two years of the TMA’s existence, representing nearly 10% of all petitions filed during that time.

A similar situation arises when the USPTO institutes a proceeding upon a petition, but then also institutes its own proceeding against the same registration. I refer to this situation as “parallel proceedings.” In these situations, the petition typically alleged nonuse with respect to only some of the goods claimed in the challenged registration, while the proceeding initiated by the USPTO claims nonuse with respect to all of the goods claimed in the challenged registration. For example, when instituting a reexamination proceeding against Registration No.6,216,319, the USPTO stated that “the original evidence provided by petitioner . . . establishes a prima facie case that the mark was not in use in commerce as of the relevant date with . . . [e]lectric hair straightener[s] [or] [f]lat irons” and that the Office’s own review had revealed “a prima facie case has been made that the mark was not in use in commerce as of the relevant date with any of the goods listed in the registration.”[42] This pattern has repeated itself thirteen times.[43]

The USPTO’s preference for reexamination proceedings over expungement proceedings is unsurprising, insofar as the remedy of cancellation is equally available in both proceedings, while the expungement proceeding bears a much higher burden of proof.[44] That is, an expungement proceeding alleges that the registered “mark has never been used in commerce on or in connection with some or all of the goods or services recited in the registration,”[45] while a reexamination proceeding merely alleges that the registrant had not used the mark as of the date they claimed to have done so when prosecuting their application.[46] One would expect that, as interested petitioners become more familiar with TMA proceedings, the expungement proceeding will be increasingly abandoned in favor of the reexamination proceeding.

Given the concerns expressed in the literature about spurious applications originating in China,[47] we can next use the dataset reported herein to investigate whether Chinese nationals’ registrations are particularly vulnerable to TMA proceedings.

Here we see that, as might have been expected, nearly two-thirds of TMA proceedings do indeed target registrations owned by Chinese nationals. This is mostly attributable to the fact that the USPTO seems to have focused most of its TMA enforcement efforts on such registrations. For petitioner-initiated proceedings, by way of contrast, roughly half of targeted registrations are owned by U.S. citizens, while only about a quarter of petitions target registrations owned by Chinese nationals.

It is difficult to draw conclusions about the importance of registrant nationality to enforcement strategies from this data. While the large number of Chinese-owned registrations caught up in USPTO enforcement activity under the TMA might on the surface suggest potential targeting on the basis of national origin, a look behind the numbers at the substance of the targeted registrations suggests other possible explanations for the large number of Chinese registrants subject to USPTO-initiated TMA proceedings. For example, the USPTO often initiates a dozen or more reexamination proceedings against Chinese-owned registrations in a single day,[48] but this is typically because all these registrations relied on the same so-called “specimen farm” website to create false evidence of use of their marks in commerce, so as to defraud the USPTO into issuing their registrations.[49] While the USPTO, once on notice of such a specimen farm, can scour it to identify any registered trademarks that appear therein and initiate multiple reexamination proceedings, private parties have little incentive to do so—and even less incentive to pay a petition fee of $400 per registered trademark they might find.[50] It is likely that the reasons motivating the USPTO to seek to clear unused applications from the register are different than the reasons motivating interested petitioners (who are likely to be moved by competitive concerns rather than abstract concern over clutter on the register). This difference in motivations may account for the difference in nationalities of the owners of registrations targeted in TMA proceedings brought by the USPTO as compared to those brought by private parties.

Another way of looking at the role of nationality in TMA proceedings is to look at the filing bases of registrations that are the subject of such proceedings. A “filing basis” is a provision of the Lanham Act that affords a trademark claimant a basis to file for a registration. The most important provisions in this regard are found in § 1 of the Act, which provides for registration of trademarks that have been “used in commerce” in the United States (under § 1(a)), or which an applicant “has a bona fide intention” to use in commerce in the United States (under § 1(b)).[51] But for foreign applicants, two other filing bases can be important. The first arises under § 44(e) of the Act, which permits the owner of a trademark registration in a foreign country that is a member of the Paris Convention to apply for and obtain a registration in the United States without having to first establish use of the mark in the United States.[52] Similarly, the owner of an international trademark registration under the Madrid Protocol is entitled to apply to extend their registration into the United States under § 66(a) of the Act based on a declaration of bona fide intent to use their internationally registered trademark in the United States, without having to first establish actual use of that mark in the United States.[53] Although in theory U.S. nationals could apply for a trademark registration under § 44(e) or § 66(a), in practice most applicants will be seeking registration in their own native country first, and will thus claim § 1(a) or § 1(b) as their filing basis. For similar reasons, applications under § 44(e) or § 66(a) are more likely to be filed by foreign applicants with already-established businesses outside the United States. As Table 3 shows, such established foreign applicants do not appear to be the primary target of TMA proceedings:

We see here that nearly all TMA proceedings are initiated against registrations that claimed actual use in the United States as a filing basis. Yet as Table 2 showed, over two-thirds of registrations that are the subject of a TMA proceeding are owned by foreign nationals or firms.[54] This seems to indicate that the types of foreign-owned registrations targeted by TMA proceedings are not connected with existing overseas businesses seeking to expand into the United States (at least, not under an established foreign brand), and thus may be more likely than other foreign-owned registrations to be spurious.

B. Proceeding Outcomes and Pendency

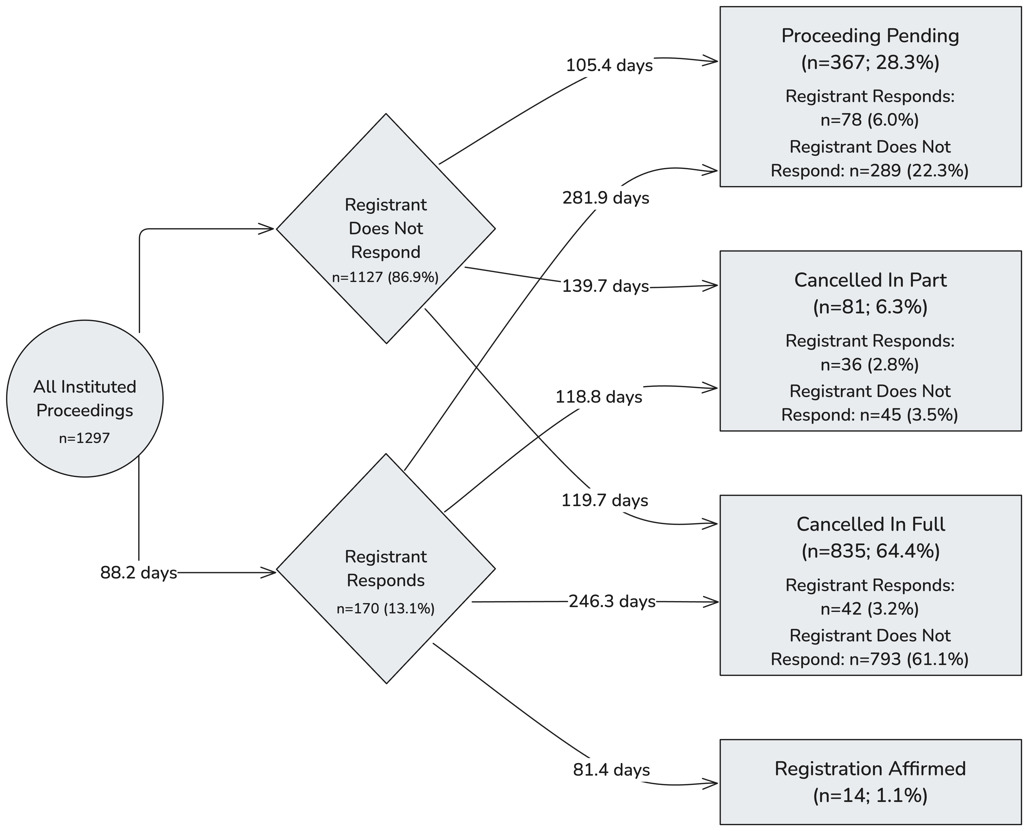

Once a registration becomes the target of a TMA proceeding, a number of different outcomes are possible. If the proceeding originates with a petition, the USPTO can either require additional information, institute a proceeding, or decline to institute a proceeding upon the petition.[55] In the latter case, the USPTO may decide to institute a proceeding on its own initiative (what I have called “commandeering” the proceeding) or may simply treat the matter as concluded. If a proceeding is instituted (either upon a petition or upon the initiative of the USPTO), the registrant may either respond or default.[56] If the registrant responds, they may do so by essentially conceding the issue and consenting to removal of any challenged goods or services, either informally by responding to the petition or any resulting office action, or more formally by filing a request under § 7 of the Lanham Act to amend their registration.[57] Whether the registrant responds or not, the proceeding will ultimately be deemed terminated by the USPTO when it completes its ex parte review process. At the end of this process, the registration may be left unchanged, may be cancelled in part (having some of the goods or services listed removed), or may be cancelled in its entirety.[58] Because TMA proceedings are still a recent phenomenon, many proceedings represented in the dataset reported in this Article are still pending at one of the intermediate stages described above.

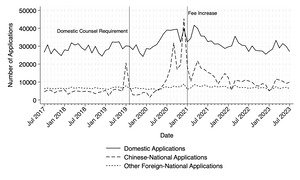

The following flowcharts show both the prevalence of outcomes of interest and the time it takes the USPTO to progress through them.

As Figure 1 shows, approximately two-thirds of petitions to commence TMA proceedings lead to the institution of such proceedings—either upon the petition or via commandeering. And as Figure 2 shows, once a petition is initiated the registrant is overwhelmingly likely to default—to allow the registration to be cancelled to the extent challenged by the proceeding.

Two features of TMA proceedings emerge from these visualizations. First, they seem to be successfully identifying at least some of the clutter on the register. Of those proceedings that have concluded, nearly all result in partial or total cancellation of the challenged registration, often with the consent of the registrant.[61] Second, these proceedings seem to be taking a considerable amount of time to clear that clutter. Where the registrant contests a proceeding (which occurs, if at all, on average about three months after institution), the proceeding can take approximately an additional six to nine months on average to resolve.[62] Indeed, the figures above simplify the procedural history of TMA proceedings to a considerable extent: often the USPTO will request that a petitioner add information to their petition to render it complete—sometimes more than once—and when a registrant responds to the institution of a proceeding, the USPTO will often request that the registrant provide additional information beyond their initial response—again, sometimes more than once.[63]

That said, the USPTO responds to petitions relatively quickly, rendering its institution decisions in an average of two to three months.[64] When proceedings are instituted and the registrant does not oppose them, terminations are relatively prompt, issuing within the four-month period (including an available one-month extension) provided by rule for the registrant to respond.[65] But where the registrant has responded to contest the proceeding and that proceeding has already terminated, the USPTO took an average of nearly an additional six months to resolve it, meaning the average contested TMA proceeding takes over eight months to resolve once it is instituted—though this calculation omits the hundreds of proceedings that remained pending at the close of the data collection period and (as already noted) have been pending for an average of nearly a year.[66] Where proceedings have been resolved, they have typically concluded within well less than a year after institution, which may seem relatively expeditious compared to a typical federal litigation matter or even to a TTAB cancellation proceeding.[67] But when we consider the huge volume of clutter believed to be on the register, and the substantial fraction of TMA proceedings that are still pending, spending several months per registration to clear a few hundred spurious registrations per year through individualized ex parte proceedings starts to resemble emptying the ocean with a teaspoon. The next section reviews statistics from the rest of the trademark registration system to illustrate the scope of the problem.

C. Other Administrative Interventions

As noted above, the USPTO undertook a number of administrative policy changes to attempt to stem the rising flood of spurious trademark registration applications over the past several years. In this section, I examine application volumes during the period covering two interventions that affect the cost of filing a trademark application: the domestic counsel requirement for foreign applicants imposed in mid-2019,[68] and the increase in application fees that became effective at the start of 2021.[69] To better situate the response to these interventions within trends that may have been underway at the time the interventions became effective, the analysis set forth herein covers the period from July 2017 through July 2022.

In the analysis that follows, an application is coded as a “Domestic Application” if the application’s owner is coded as a U.S. citizen in the USPTO’s Trademarks Case Files dataset, or if the owner’s national citizenship is not indicated but the owner is coded as the citizen of a U.S. state. An application is coded as a “Chinese-National Application” if either the owner is coded as a citizen of China in the USPTO’s Trademarks Case Files dataset, or the owner’s national citizenship is not indicated but the owner’s address is listed and that address is in China. An application is coded as an “Other Foreign-National Application” if either the application’s owner’s national citizenship is coded in the USPTO’s Trademark Case Files Dataset as being of a nation other than the United States or China, or if the owner’s national citizenship is not indicated but the owner’s address is listed and that address is neither in China nor in the United States. Because some applications and registrations list multiple owners, and because some owners have multiple countries associated with them in the Case Files dataset, some applications are coded in multiple categories in the analysis below.[70]

The huge spikes in applications of Chinese origin just prior to the effective dates of the USPTO’s administrative interventions, combined with the huge drops in such applications immediately following those interventions, obviously suggest that those interventions have had a substantial effect on applicant behavior. But we must note at the outset that it is not entirely clear that the interventions have reduced application volumes as intended. Rather, it may simply be that they shifted applications earlier in time. That is, a Chinese citizen planning to apply for a trademark registration in the United States, and knowing that the cost of such an application is likely to go up in the near future (either because the applicant will need to pay a higher fee or will need to hire a U.S.-licensed attorney), would likely take particular care to file their application before the cost increase goes into effect rather than after.[72] But even if that were the right interpretation of this chart, we would still be left with an important inference: Chinese nationals applying for U.S. trademark registrations appear to be extremely price-sensitive—more price-sensitive, indeed, than other applicants. We see no similar spikes and drops in application volumes from domestic or other foreign-national applicants around the times of the two administrative interventions in the study.

Another important feature of this chart is the way application volumes compare to the volume of TMA proceedings described in the previous section. It is notable that the decrease in the volume of applications originating in China between the month prior to the imposition of the domestic counsel requirement and the month following the imposition of that requirement is roughly an order of magnitude larger than the number of registrations that have ever been the subject of a TMA proceeding in those proceedings’ two-year history. Similarly, the decrease in application volume originating in China from the month before the increase in application fees to the month after that increase is more than twenty times the entire volume of TMA proceedings over the past two years. The effective date of these changes to the USPTO’s trademark fee schedule roughly coincided with the enactment of the TMA—both occurred in December of 2020—but preceded the effective date of the TMA’s expungement and reexamination provisions by approximately a year.[73] Indeed, by the time the first TMA proceeding was instituted in February of 2022, the volume of applications filed by Chinese nationals and firms had substantially retreated from its historic peaks.[74] Nevertheless, every month, roughly an additional 10,000 applications are filed by Chinese nationals and firms. Again, this is approximately twenty times the annual volume of TMA proceedings. That is to say nothing of the other roughly 30,000 applications filed every month by domestic applicants or the additional roughly 10,000 applications filed every month by foreign applicants from outside of China. To be blunt, TMA proceedings do not even represent a rounding error against the scope of applications for federal trademark registrations.

IV. Discussion

The foregoing analyses suggest that TMA proceedings likely do little harm beyond taxing the USPTO’s examiner corps, and represent an improvement over previously existing tools available to the public for helping to clear otherwise identified register clutter, but are not a plausible solution to what appears to be a substantial problem. The basic problem appears to be twofold. First, TMA proceedings rely on human intervention—an examiner reviewing the record of an individual registration—to address a problem that operates at a superhuman scale—the collective activity of automated, algorithmic e-commerce and electronic registration application tools. And second, these proceedings rely on human beings—interested third parties or USPTO personnel—to invest their time and effort in seeking out, identifying, and proving up examples of spurious trademark registrations. That work is costly, and those costs must be imposed on somebody, or the work will not be done.

The main problem of TMA proceedings is that they appear to misallocate these costs. The least expensive form of application for a trademark registration carries a fee of only $250.[75] The fee to file a petition to expunge or reexamine a spurious trademark is $400.[76] The USPTO—a self-funded agency that has substantial authority to set its own fee schedule and that relies on fee revenues to fund its operations[77]—has effectively made it cheaper for a bad-faith actor to clutter the register than for a good-faith actor to de-clutter it. And even where the USPTO itself undertakes to initiate investigations into spurious registrations, it must either pass those costs on to users of the Office’s services in the form of higher fees, or it must divert resources that it might otherwise put to work performing the Office’s other functions, degrading those functions at a cost to their users.

In contrast, we have seen that among the most effective means of reducing the volume of suspect applications may be to impose greater costs on bad-faith applicants themselves. Requiring foreign filers to hire domestic counsel, threatening applicants with fees if they claim goods and services they later have to disclaim, and increasing the base cost of a registration all correlated with a substantial reduction in applications from China—which is where a disproportionate share of spurious applications and registrations are thought to originate from—without substantially reducing applications from elsewhere.[78] But there are at least three obvious objections to this argument. The first is that not all trademark applications filed by Chinese nationals and firms are spurious. Many—perhaps most—are perfectly legitimate. The second is that applications originating elsewhere can also be spurious—the analysis in Section III.A above of TMA proceedings to date demonstrates that to be the case. And the third is that many of these cost-raising measures, even if they are effective in reducing the volume of spurious applications, fail to discriminate between good-faith and bad-faith actors: higher application fees and the costs of retaining counsel impact legitimate and spurious applicants alike.

This is the central challenge of administering the systems that human beings rely on in our increasingly automated world. Automated systems are extremely vulnerable to bad-faith behavior that exploits information that is important to the human beings who depend on the system but invisible to the machines and algorithms that drive it. Large language models trained only on undifferentiated mountains of text cannot discriminate between information and disinformation, earnestness and sarcasm, expertise and ignorance. Thus, when we look to such models for reliable facts about the world, we are likely to be led seriously astray.[79] Algorithmic filters cannot tell whether a social media user is a human being or a bot, let alone whether the user’s latest post is true or false, a joke or a threat.[80] And—though it may seem a less important issue in comparison—trademark rights that are legitimated by the use of a mark in commerce cannot function if they depend on human judgment to intervene any time an algorithmic commerce platform creates an incentive to generate a spurious illusion of such use in commerce. If we hope to clamp down on such spurious claims of rights, we will need to find a way to address—or counteract—the incentives themselves.

V. Conclusion

This Article has presented the first empirical analysis of the new expungement and reexamination proceedings established by the Trademark Modernization Act. That analysis shows that TMA proceedings are a fairly reliable and reasonably expeditious administrative pathway for clearing identified spurious applications from the register, but that they are not likely to be a useful tool for combatting the type of bad-faith spurious applications and registrations that have become a symptom of our age of automated, algorithmic e-commerce. While TMA proceedings are certainly preferable to lengthier and more expensive inter partes administrative proceedings when it comes to clearing spurious registrations, they do not address the structural characteristics of trademarks in automated commerce that make obtaining such registrations a winning competitive strategy.

VI. Appendix

Construction of the dataset reported herein began by collecting all entries listed on the USPTO’s online “Trademark Decisions and Proceedings” webpage (hereinafter TMA dockets).[81] These entries correspond to a subset of docket entries in TMA proceedings, and include the challenged registration’s serial number, registration number, filing basis, and mark text or image; the name and citizenship of the registrant; the type and docket number of the proceeding; the name of the petitioner (if any); and the date and type of each document filed in the proceeding. Based on this data, I used the USPTO’s Trademark Status Document Retrieval (TSDR) API to gather the full prosecution history for each registration that appears in the TMA dockets, including the date, docket description, and URL for every document that is part of the registration’s case file (hereinafter TSDR dockets). Finally, I used a combination of algorithmic coding and hand coding to generate various indicator and date variables for lifecycle events of interest for each registration. Where a docket includes multiple instances of a particular category of event, the dataset reports the earliest such instance. Because (1) the TMA dockets appear to omit a small number of relevant documents that appear in the TSDR dockets; (2) some registrations have multiple TMA proceeding docket numbers associated with them; and (3) the TSDR dockets do not index TMA docket number information, the dataset will have some gaps that were impossible to fill algorithmically. Where hand coding revealed such a gap in a way that allowed me to add the missing information to the dataset, I have done so, but some gaps almost certainly remain.

Algorithmic coding based on docket entry text allowed for identification of many lifecycle events of interest, such as registration dates, responses to office actions, and so on. However, many proceedings had docket entries indicating the proceeding had been terminated or had been the subject of a final office action, but did not include separate docket entries for cancellations or amendments of the registrations under review. Moreover, spot checks of the underlying documents revealed that this did not necessarily indicate that the USPTO had concluded that the registration should be affirmed. Rather, many terminations indicate that the registration had been voluntarily amended, or even surrendered, or that the registration would be cancelled in whole or in part due to the registrant’s failure to respond to the proceeding, but no subsequent docket entry had yet appeared confirming those results (apparently but not always because the time to appeal had not expired by the end of the data collection period). In many other proceedings, the relevant outcome was only recorded in the TMA dockets data for a commandeered or parallel proceeding against the same registration. I therefore reviewed every memorandum terminating a TMA proceeding that I could not algorithmically associate with an outcome, and hand-coded the outcome. This means I have coded some outcomes as final that might conceivably be modified after the end of the data collection period, though this is unlikely. Proceedings with a “final” office action but no notice of termination docketed are coded as “Instituted but Still Pending,” because registrants have at least three months to respond to such a final office action. Proceedings subject to a pending request for reconsideration or appeal at the close of the collection period are likewise coded as “Instituted but Still Pending.”

The resulting dataset includes 1,528 observations and 35 variables. Each observation uniquely identifies a single TMA proceeding docket number (omitting the “E” or “R” suffix that the USPTO has inconsistently used to identify whether the proceeding is for expungement or reexamination). The variables are described in the chart below.

Trademark Modernization Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-260, 134 Stat. 2200 [hereinafter TMA] (codified in scattered sections of 15 U.S.C.).

Id. § 226, 134 Stat. at 2208 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1116(a) (Supp. IV 2023)).

See eBay, Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 391 (2006). This change was consistent with the suggestions of a number of commentators who had argued that eBay, while suitable in patent and copyright law, was an ill fit for trademark law. See generally Peter J. Karol, Trademark’s eBay Problem, 26 Fordham Intell. Prop., Media & Ent. L.J. 625 (2016); Mark A. Lemley, Did eBay Irreparably Injure Trademark Law?, 92 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1795 (2017).

See TMA § 228, 134 Stat. at 2209–10 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §§ 1068, 1070, 1092 (Supp. IV 2023)).

See United States v. Arthrex, Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1970 (2021); see also Jennifer Mascott & John F. Duffy, Executive Decisions After Arthrex, 2021 Sup. Ct. Rev. 225, 226–27 (2022).

The statute also codifies the previously informal “letter of protest” practice by which the USPTO will accept evidence from third parties opposing an application for registration during the ex parte examination process. TMA § 223, 134 Stat. at 2201 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1051(f) (Supp. IV 2023)).

See generally Georg von Graevenitz et al., Trade mark Cluttering: An Exploratory Report (2012), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7dd76d40f0b65d88634bcf/ipresearch-tmcluttering.pdf [https://perma.cc/B43B-9UY9].

See id. at 10–11. Indeed, in the aggregate in the United States, concern has been raised that trademarks are becoming scarce due to the registration of nearly all of the most common English words as trademarks in nearly all categories of goods and services. Barton Beebe & Jeanne C. Fromer, Are We Running Out of Trademarks? An Empirical Study of Trademark Depletion and Congestion, 131 Harv. L. Rev. 945, 981–82, 992–93 (2018).

See Post Registration Audit Program, U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/maintain/post-registration-audit-program [https://perma.cc/VW6M-NNHJ] (last visited Nov. 18, 2024). The USPTO claims authority for this audit program under regulations that charge the agency “to assess and promote the accuracy and integrity of the register.” See id.; 37 C.F.R. §§ 2.161(b), 7.37(b) (2023).

Post Registration Audit Program Statistics, U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/maintain/post-registration-audit-program-statistics [https://perma.cc/22P9-7BXA] (last visited Nov. 18, 2024); Post Registration Audit Program, supra note 10.

See U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., Trademarks and Patents in China: The Impact of Non-Market Factors on Filing Trends and IP Systems 3–5 (2021), https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/USPTO-TrademarkPatentsInChina.pdf [https://perma.cc/P8R7-NBUB]; Barton Beebe & Jeanne C. Fromer, Fake Trademark Specimens: An Empirical Analysis, 120 Colum. L. Rev. F. 217, 225–26 (2020); Josh Gerben, Massive Wave of Fraudulent US Trademark Filings Likely Caused by Chinese Government Payments, Gerben Intell. Prop., https://www.gerbenlaw.com/blog/chinese-business-subsidies-linked-to-fraudulent-trademark-filings [https://perma.cc/KQP3-ND4Z] (last visited Nov. 19, 2024).

See Committee on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, New and Full Notification Pursuant to Article XVI:1 of the GATT 1994 and Article 25 of the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures: China, at 97, 125, WTO Doc. G/SCM/N/401/CHN (July 20, 2023), https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/G/SCM/N401CHN.pdf&Open=True [https://perma.cc/3ZMC-D4BR].

See Jeanne C. Fromer & Mark P. McKenna, Amazon’s Quiet Overhaul of the Trademark System, 113 Calif. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2025) (manuscript at 3–4, 32); Note, Fanciful Failures: Keeping Nonsense Marks off the Trademark Register, 134 Harv. L. Rev. 1804, 1810, 1814 (2021).

See generally Rae Yule Kim, The Impact of COVID-19 on Consumers: Preparing for Digital Sales, IEEE Eng’g Mgmt. Rev., Sept. 2020, at 212; Cameron Guthrie et al., Online Consumer Resilience During a Pandemic: An Exploratory Study of e-Commerce Behavior Before, During and After a COVID-19 Lockdown, J. Retailing & Consumer Servs., July 2021; Impact of COVID Pandemic on eCommerce, Int’l Trade Admin., https://www.trade.gov/impact-covid-pandemic-ecommerce [https://perma.cc/629H-QCE5] (last visited July 10, 2024).

See generally Fromer & McKenna, supra note 14.

15 U.S.C. § 1066a (Supp. III 2022).

15 U.S.C. § 1066b (Supp. III 2022).

15 U.S.C. §§ 1066a–1066b (Supp. III 2022).

H.R. Rep. No. 116-645, at 13 (2020).

Id. at 11 (footnotes omitted).

See TMA, § 225(g), 134 Stat. 2200, 2202–03; Changes to Implement Provisions of the Trademark Modernization Act of 2020, 86 Fed. Reg. 64300 (Nov. 17, 2021) (to be codified at 37 C.F.R. pts. 2, 7).

See infra Parts II, III.

See supra notes 10–11 and accompanying text.

Requirement of U.S. Licensed Attorney for Foreign Trademark Applicants and Registrants, 84 Fed. Reg. 31498 (July 2, 2019) (to be codified at 37 C.F.R. pts. 2, 7, 11).

TEAS Login Requirement, U.S Pat. & Trademark Off. (Sept. 23, 2019), https://www.

uspto.gov/about-us/news-updates/teas-login-requirement [https://perma.cc/V5U4-QMZ8].Trademarks USPTO.gov Account ID Verification Program, 87 Fed. Reg. 41114 (July 11, 2022).

Trademark Fee Adjustment, 85 Fed. Reg. 73197–99 (Nov. 17, 2020) (to be codified at 37 C.F.R. pts. 2, 7).

See Post Registration Audit Program, supra note 10.

Trademark Decisions and Proceedings: Expungements/Reexamination Proceedings, U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., https://developer.uspto.gov/tm-decisions/search

/expungement [https://perma.cc/6MDQ-WV9D] (last visited Aug. 27, 2024).Trademark Case Files Dataset, U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., https://www.uspto.gov/i

p-policy/economic-research/research-datasets/trademark-case-files-dataset [https://perma.cc/87

MY-NN6V] (last visited Sept. 15, 2024). The datasets constructed for this paper make use of the latest update to Case Files, which is current through March of 2024. See id.Trademark Status & Document Retrieval, U.S. Pat. & Trademark Off., https://tsdr.uspto.gov/ [https://perma.cc/SB5Q-LD2D] (last visited Sept. 26, 2024).

The dataset is available on Zenodo. See Jeremy Sheff, Trademark Modernization Act Dockets Dataset, Zenodo (July 18, 2024), https://zenodo.org/records/12775326 [https://p

erma.cc/C4KK-8D24].See infra Sections III.A, III.B.

See infra Section III.C. While a difference-in-difference regression analysis might provide additional support for any causal inferences that we might wish to draw from these interactions, space does not permit it here, and such analysis is reserved for future work.

Compare 15 U.S.C. § 1066a (Supp. III 2022), with 15 U.S.C. § 1066b (Supp. III 2022).

Compare 15 U.S.C. §§ 1066a(a), 1066b(a) (Supp. III 2022) (providing that “any person may file a petition” to commence an expungement or reexamination proceeding, respectively), with 15 U.S.C. §§ 1066a(h), 1066b(h) (Supp. III 2022) (providing that “[t]he Director [of the USPTO] may, on the Director’s own initiative, institute” an expungement or reexamination proceeding, respectively).

See Sheff, supra note 33. A “filing basis” in trademark law is the statutory authority for the applicant’s request for a registration. These filing bases are typically referred to by the session law section of the Lanham Act that provides for them. Thus “1(a)” indicates a use-based application under Section 1(a). Lanham Act of 1946, Pub. L. No. 87-772, § 1(a), 60 Stat. 427 (1946) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1051(a)); “1(b)” indicates an intent-to-use application under Section 1(b). § 1(b) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1051(b)); “44(d)” indicates an application claiming priority based on a foreign application under Section 44(d). § 44(d) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1126(d)); “44(e)” indicates an application based on a foreign registration under Section 44(e). § 44(e) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1126(e)); and “66(a)” indicates an application to extend protection in the United States for an international registration under the Madrid Protocol, under Section 66(a). § 66(a) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1141f(a)).

See supra Table 1. I have coded proceedings as “commandeered” in the dataset in two circumstances. The first occurs in only two dockets, where the petitioner’s petition is rejected but the USPTO institutes a TMA proceeding shortly thereafter on its own initiative using the same docket number. The other involves multiple docketed proceedings against the same registration. I have coded all such proceedings as “commandeered” if a petition was filed in one of the proceedings, the petition was rejected, and a proceeding was instituted on or after the date the petition was rejected. Thus, the docket number corresponding to the original petition will be coded as commandeered, as will any separate docket number corresponding to the director-initiated proceeding. This will have the effect of inflating the number of commandeered proceedings insofar as the challenge to a registration in such proceedings will essentially be counted twice----once for the petition and once for the USPTO’s subsequent action----but this is necessary to preserve the independence of each docket in the dataset.

See 37 C.F.R. § 2.91(c) (2023) (setting forth requirements for a complete petition).

Notice of Non-Institution, Registration No. 7,159,298 (USPTO Feb. 16, 2024), https://tsdr.uspto.gov/documentviewer?caseId=sn97473128#docIndex=2&page=1 [https://perma.cc/HMN4-38V2] (regarding Petition No. 2023-100858).

Combined Notice of Institution and Nonfinal Office Action, Registration No. 7,159,298 (USPTO Feb. 16, 2024), https://tsdr.uspto.gov/documentviewer?caseId=sn97473128#docIndex=3&page=1 [https://perma.cc/B7L3-BKH8] (regarding Proceeding No. 2024-100947R).

Combined Notice of Institution and Nonfinal Office Action, Registration No. 6,216,319 (USPTO Dec. 8, 2022), https://tmng-al.uspto.gov/resting2/api/casedoc/cms/case/88922400/office-action/OfficeAction4987419.pdf [https://perma.cc/NXA3-ZDB9] (regarding Proceeding No. 2022-100244R).

See supra Table 1.

15 U.S.C. §§ 1066a(g), 1066b(g) (Supp. III 2022).

See id. § 1066a(a).

See id. § 1066b(a)–(b).

See supra text accompanying note 12.

As can be seen in the dataset underlying this Article, the USPTO did so on several days in August of 2023, for example.

Third Parties Can Challenge Applications or Registrations with Invalid Specimens from e-Commerce Specimen Farm Websites, U.S Pat. & Trademark Off., https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/protect/challenge-invalid-specimens [https://perma.cc/RYV8-PKH2] (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

See id.; 37 C.F.R. § 2.6(a)(26) (2023) (establishing a fee of $400 per class of goods and services for the filing of a petition for expungement or reexamination).

Lanham Act of 1946, Pub. L. No. 87-772, § 1(a), (b), 60 Stat. 427 (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1051(a), (b)). Though § 1(b) provides that an application can be filed prior to actual use of the mark in the United States, and that such an application establishes priority over later applicants so long as a registration ultimately follows from that application, no registration can issue until the applicant actually uses their mark in the United States. See 15 U.S.C. §§ 1051(d), 1057(c).

See Lanham Act § 44(b), (e) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C § 1126(b), (e)); see also World Intell. Prop. Org. [WIPO], Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property art. 6(2), 6quinquies(A)(1), TRT/PARIS/001 (as amended on Sept. 28, 1979), https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text/288514 [https://perma.cc/DT6C-LW2X].

See Lanham Act § 66(a) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1141f(a)); see also World Intell. Prop. Org. [WIPO], Protocol Relating to the Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks arts. 1–2, TRT/MADRIDP-GP/001 (as amended on Nov. 12, 2007), https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text/283483 [https://perma.cc/5FKM-APLH].

See supra Table 2.

See 37 C.F.R. §§ 2.91, 2.92 (2023).

See id. §§ 2.92, 2.93.

Section 7(e) allows registrants, upon payment of an appropriate fee, to amend or disclaim their registration in whole or in part. Lanham Act § 7(e) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1057(e)).

See 37 C.F.R. § 2.93.

Pendency figures overlaid over the flowchart arrows are calculated means.

Pendency figures overlaid over the flowchart arrows are calculated means.

See supra Figure 2.

Even where the registrant ultimately defaults, an instituted proceeding will be pending for at least three months, as this is the period of time granted by rule for the registrant to reply with evidence of its use of the mark, and this period can be extended for an additional month upon payment of a fee. 37 C.F.R. § 2.93(b), (c). In practice, as Figure 2 shows, the USPTO appears to terminate TMA proceedings only after the registrant has had four months to respond and has failed to do so in that time. See supra Figure 2.

The earliest of each of these requests is reflected in the dataset accompanying this Article; see infra Part VI, for additional details.

See supra Figure 1.

See supra note 63.

See supra Figure 2.

Trial proceedings (i.e., opposition and cancellation proceedings) at the TTAB had an average pendency of 156.5 weeks in fiscal year 2024. See TTAB Incoming Filings and Performance Measures for Decisions: Fiscal year (FY) 2024, U.S Pat. & Trademark Off., https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/ttab/ttab-incoming-filings-and-performance [https://perma.cc/6MAJ-QRMA] (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

See supra note 25 and accompanying text.

See supra note 28 and accompanying text.

Specifically, over the six-year period under investigation, 5,818 applications are coded as both Domestic and Chinese-National, 15,424 applications are coded as both Domestic and Other-Foreign-National, 3,037 applications are coded as both Chinese-National and Other-Foreign-National, and 82 applications are coded in all three categories (this is out of a total of over 3.4 million applications with a recorded application filing date during the period of the analysis).

Application volume data is derived from the USPTO Trademark Case Files Dataset, supra note 31.

To try to further support a causal inference regarding the effects of these interventions on application volumes would, again, require additional analysis that is beyond the scope of this Article, but which may be the subject of future work.

See supra notes 22, 28 and accompanying text.

See supra Figure 3.

37 C.F.R. § 2.6(a)(1)(iv) (2023).

Id. § 2.6(a)(26).

See 35 U.S.C. § 42; Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, Pub. L. No. 112-29, § 10, 125 Stat. 316 (2011); Study of Underrepresented Classes Chasing Engineering and Science Success Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-273, § 4, 132 Stat. 4158, 4159.

See supra notes 12–14 and accompanying text; supra Figure 3.

See Shira Ovide, Why Google’s AI Might Recommend You Mix Glue into Your Pizza, Wash. Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2024/05/24/google-ai-overviews-wrong/ [https://perma.cc/6QFX-R3CH] (last updated May 24, 2024, 3:07 PM) (“AI cannot tell the difference between a joke and a fact. Or if the AI doesn’t have enough information to give you an accurate answer, it might invent a confident-sounding fiction, including that dogs have played professional basketball and hockey.”).

See generally Tarleton Gillespie, Content Moderation, AI, and the Question of Scale, Big Data & Soc’y, Aug. 21, 2020.

Trademark Decisions and Proceedings, supra note 30.