I. Introduction

Trademark law protects a mark as a unique commercial symbol for a firm’s goods and services if the mark distinguishes the owner’s products from those of others.[1] When a newcomer enters the market selling a similar product bearing a similar mark, the owner may bring an action for trademark infringement. To secure relief from allegedly infringing activity, the owner must establish that if the newcomer continues on their current course, consumer confusion is likely. Courts assessing likely confusion give significant weight to whether the newcomer’s adoption of a commercial symbol was in bad faith. Scholars criticize the focus on bad faith, because unlike other likelihood of confusion factors, the newcomer’s intent seems irrelevant to a consumer’s perception about confusing overlap between competitors.[2]

This Article argues these critiques are somewhat misguided in light of theories about how information is transmitted in communication systems. Properly calibrated legal systems can incentivize better information flow and appropriate behavior by commercial actors using information-forcing default rules. Defendants who run afoul of the bad faith inquiry are frequently engaging in behavior that increases consumer-confusing noise or interference in the market, reducing consumers’ ability to receive sufficiently clear signals about the products they would prefer to purchase. Courts should thus continue to consider bad faith in trademark litigation, with some modest adjustments.

Part II outlines what mark owners must show to secure trademark protection and how the bad faith inquiry plays a key role in trademark litigation, then summarizes critiques of this role. Part III considers trademark law’s information transmission function in light of legal theories about the efficiencies captured through information-forcing rules, as well as Claude Shannon’s information theory, which provides a model for information transmission and important insights for how to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio and manage source interference in the commercial market.[3] Part IV applies these theories in a modest defense of the bad faith inquiry in trademark litigation.

II. Validity, Infringement, and Intent

A valid trademark ideally informs consumers that the product bearing the mark comes from a consistent, if anonymous, source. When a newcomer adopts a trademark that is found likely to confuse consumers,[4] the mark owner can prevent continued use and (sometimes) recover damages for prior uses.[5] If a fact finder concludes the newcomer’s use was intentional, willful, or in bad faith, the risk of liability increases, along with the consequences of liability.[6] And the absence of bad faith or presence of good faith is a precursor to some defenses against a claim of trademark infringement.[7]

A. Trademark Ownership: Acquiring Source Significance

Trademark law secures to the mark owner the exclusive right to use a trademark (a word, name, symbol, or device) in commerce to indicate the source of the seller’s product.[8] Some symbols inherently distinguish source because the symbol is effectively unrelated to the product.[9] These inherently distinctive symbols qualify for trademark protection from the mark owner’s first use in commerce.[10]

Other symbols describe the seller’s product and thus do not inherently distinguish source. To secure trademark protection in these descriptive symbols, the mark owner must establish that the mark has acquired a secondary or source signifying meaning.[11] Courts evaluate direct evidence that consumers see the mark as a source identifier, typically through surveys of a relevant sample of likely purchasers.[12] Courts also gauge indirect evidence of source significance like the advertising budget of the mark owner, the length of use of the mark in the market, unsolicited media coverage, and the owner’s volume of sales.[13] The information the mark owner must reveal is difficult to generate unless the owner has engaged in reasonable and relatively costly efforts to communicate with consumers.[14]

Barring restrictions grounded in competition concerns,[15] a source signifying trademark is valid and protectable.[16] Consumers can rely on the mark to reduce search costs because trademark law prevents a newcomer from using a mark that is too similar to the owner’s valid mark on products that are too similar to those offered by the owner.[17] Trademark protection thus encourages the mark owner to maintain consistent quality and spend capital transmitting information to consumers because the mark owner can internalize the benefit from those activities.[18] If the law secures the mark owner’s relatively exclusive right to use its mark on its products, the consumer knows their next experience with a marked product should be consistent with the last one.[19] The law thus encourages a newcomer to select a mark for its products that is distinguishable from valid marks already in use. Trademark law preserves this information transmission function by imposing liability on newcomers who adopt marks that are likely to confuse consumers.[20]

B. Trademark Infringement: Likelihood of Confusion

Courts engage in a multifactor analysis to determine whether a newcomer’s use of a mark is confusingly similar to the owner’s use.[21] Each circuit court uses a slightly different test to determine whether confusion is likely, but five factors are considered in virtually every circuit: (1) the similarity of the marks, (2) the proximity of the products, (3) the strength of the owner’s mark, (4) evidence of actual consumer confusion (including survey evidence), and (5) the newcomer’s intent.[22]

Similarity of the marks and proximity of the products are intuitively sensible factors to consider. A newcomer selling the same product as the owner, using an identical mark, will likely confuse consumers.[23] The wider the difference between the owner’s mark and the newcomer’s mark and the wider the difference between the products of the owner and newcomer, the less likely a reasonable consumer will be confused by the newcomer’s use.[24]

Trademark owners rarely have direct evidence of consumer confusion, but courts accept survey evidence as probative of actual confusion or to refute allegations of the same.[25] The higher the percentage of surveyed consumers who indicate confusion between the newcomer’s mark and that of the owner, the greater the chance a court will find the use likely to confuse consumers.[26]

Likelihood of confusion analysis also considers the strength of the owner’s mark. The strength inquiry mirrors the validity inquiry.[27] Courts presume that inherently distinctive marks are strong, while presuming that descriptive marks that acquired distinctiveness are comparatively weak.[28] Nonetheless, many descriptive marks develop exceedingly broad commercial strength over time. For example, COCA-COLA is an inherently descriptive signifier. The product sold under the COCA-COLA mark is derived from kola nuts and coca leaves. But the mark has acquired substantial commercial strength through years of relatively exclusive use, strong sales, and substantial advertising expenditures.[29]

The acquired distinctiveness and commercial strength tests both operate like information-forcing penalty default rules.[30] When a hopeful mark owner adopts a descriptive signifier, trademark priority is established when the mark acquires source significance sufficient that consumers see the mark as designating source. The desired legal status—trademark validity—is withheld until the mark owner provides sufficient evidence of acquired distinctiveness.[31] Likewise, the scope of trademark protection is cabined unless the mark owner can establish commercial strength through evidence of resource expenditure and consumer perception.[32] The stronger the mark, the more likely a court will find that alleged infringement is likely to confuse consumers.[33]

C. Intentional Infringement Increases Risk of Liability

Among the likelihood of confusion factors, the newcomer’s bad faith or intent has a strong influence on the outcome in trademark litigation.[34] For instance, a study of district court cases by Barton Beebe reported that the owner always prevailed if a court concluded the marks were similar and the newcomer’s use was in bad faith.[35]

Some nineteenth-century English and American trademark decisions required the plaintiff to establish the defendant’s fraudulent intent to secure relief, but by the turn of the twentieth century, trademark law shed the vestiges of intent-based liability and was completing its turn to a strict liability regime.[36] Thus, the plaintiff need not prove the newcomer’s bad faith or intent to pass off to establish trademark infringement.[37] Similarly, good faith or innocent adoption does not spare the defendant if confusion is likely.[38]

But bad faith or intentional infringement still influences the outcome in trademark litigation. If a court concludes that the newcomer uses its mark with the intent to confuse consumers, or exploit the owner’s goodwill and reputation,[39] the court may assume that the use will succeed as intended, and thus, the intent to confuse or free ride leads to an inference that the defendant achieved its goal and confusion occurred.[40] Thus, the court in Grey v. Campbell Soup Co. noted that when the newcomer “knowingly adopts a confusingly similar mark, it is presumed that the public is deceived.”[41]

Bad faith or newcomer’s intent is relevant at other stages in trademark litigation as well. In some circuits, evidence that the newcomer intentionally copied the owner’s mark is probative of the mark’s distinctiveness.[42] Two sellers can potentially use the same mark in geographically distinct areas without triggering liability, but that requires a showing that the newcomer adopted its mark in good faith.[43] Descriptive and nominative fair use defenses consider whether the newcomer’s use was made in good faith or with the intent to confuse.[44] Similarly, expressive use defenses assess the newcomer’s commercial motives.[45] Contributory liability for another’s infringement turns on the contributor’s specific knowledge of infringement.[46] Internet-based infringement regimes in the United States and internationally require a showing that the defendant adopted a domain name in bad faith.[47] Similarly, attorneys’ fees and disgorgement of profits focus, in significant part, on whether the newcomer willfully infringed the owner’s mark.[48]

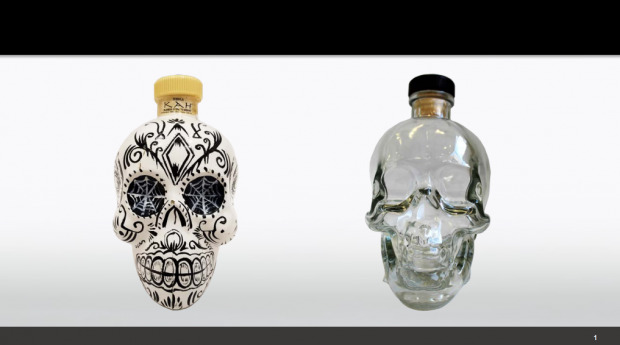

Evidence of bad faith intent thus may well shift the outcome in a trademark dispute, effectively expanding the scope of a plaintiff’s rights. Consider Globefill Inc. v. Elements Spirits, Inc.[49] Plaintiff Globefill marketed vodka in a clear glass skull-shaped decanter. Shortly after the launch of Globefill’s Crystal Skull vodka, defendant Elements Spirits began selling a variety of tequilas, including a clear tequila, in skull-shaped bottles that resembled calaveras, the decorative sugar skulls used in the Mexican celebration of the Day of the Dead.[50] In a jury trial in 2013, later reversed for Element Spirits’ trial misconduct, a jury found that confusion was unlikely.[51]

On retrial, the designer of defendant’s bottle took the stand and testified that Element Spirits’ CEO approached him about crafting a skull bottle. When she did not like the initial result, the CEO brought him plaintiff’s bottle to make a new cast. Even worse, shortly before the designer testified in court, the CEO approached him with a check for “unpaid royalties” and admitted that she lied under oath when she testified that she had not seen Globefill’s bottle until after the Element Spirits bottle was designed.[52] After hearing evidence of this behavior, the jury deliberated four hours before returning a finding of likely confusion. One cannot say for sure that the only difference facing the two juries was the evidence of bad faith, but it is certainly a salient piece of evidence heard only by the jury that found likelihood of confusion.[53]

Establishing bad faith requires the court to assess circumstantial evidence. Globefill notwithstanding, plaintiffs rarely find direct evidence of bad faith or willful infringement.[54] Courts consider a number of elements when trying to assess whether a newcomer adopted its mark in bad faith. Courts will consider whether the newcomer was aware of the owner’s mark,[55] whether the newcomer persisted in its behavior after being notified,[56] and whether the newcomer made reasonable efforts to reduce the risk of confusion, like conducting a trademark search.[57] Courts will also assess the effort the newcomer makes to communicate differences between its products and those of the owner. Failure to advertise, for example, suggests the intent to benefit from the owner’s goodwill and reputation, rather than communicate with consumers,[58] just as advertising is relevant to the mark owner’s claims of acquired distinctiveness and commercial strength.[59]

Courts nonetheless recognize that some intentional behavior does not count as trademark infringement. For example, an attempt to claim trademark rights in a generic product designation, like COMPUTER for computers, would be met with appropriate hostility by courts and the trademark office.[60] Therefore, a newcomer might intentionally adopt a generic signifier already used by an owner, but should not be sanctioned for so doing. Likewise, functional elements—like dual springs on a traffic sign designed to help it stand in the wind[61]—are not subject to trademark protection.[62] Thus, intentionally copying functional elements of a product’s design does not infringe a trademark. Finally, the intent to parody or comment on the owner’s mark does not count as evidence of bad faith.[63]

Bad faith is outcome determinative in some cases, but many scholars argue it should not be. Bartholomew argues that the intent factor may mask a court’s normative judgments about the newcomer, requiring the newcomer to demonstrate their investment in the market even though the failure to invest is largely irrelevant to consumer confusion.[64] Yen expresses concern that in many cases, “courts actually use intent to impose liability when inferences supporting confusion make little sense.”[65] Yen further argues that the current bad faith test incorrectly penalizes defendants for behavior that merely recklessly increases or occurs despite defendant’s indifference to the risk of consumer confusion.[66] Bone finds it normatively desirable to penalize intent to deceive but argues the intent inquiry does not belong among the likelihood of confusion factors, which should be empirical and predictive, rather than normative.[67] Murphy and Tierney separately argue that the costs of the intent inquiry outweigh what they view as its modest benefits.[68] Casagrande’s proposal is more dramatic, urging courts excise intent from the confusion analysis altogether.[69]

Critics reference My-T Fine Corporation v. Samuels as a case where intent swamped more important considerations.[70] In My-T Fine, the defendant changed the packaging of its pudding to more closely resemble plaintiff’s packaging over time.[71] Many of the copied elements of the packaging were not protectable, like instructions for how to make the pudding thicker or thinner.[72] There was no evidence of any consumer confusion produced by the defendant’s behavior.[73] Indeed, the court in My-T Fine admitted that the case was weak, and the court would “scarcely feel justified in interfering,”[74] if “not for the evidence of the defendants’ intent to deceive and so to secure the plaintiff’s customers.”[75] While bad faith was implied from copying mostly unprotectable elements, the court nevertheless concluded that, in light of incremental changes in defendants’ packaging to more closely resemble the plaintiff’s, the “late comer who deliberately copies the dress of his competitors already in the field, must at least prove that his effort has been futile.”[76]

My-T Fine and cases like it suggest that intent is more than one among many factors in a likelihood of confusion analysis, and that perhaps a plaintiff can prevail by proving nothing more than bad faith.[77] If the inquiry into intent is improperly targeted, a newcomer whose use is not otherwise likely to confuse could be penalized for that use because the court views the use as undertaken in bad faith. But as Part III argues, the intent factor in likelihood of confusion cases has underappreciated virtues as an information-forcing and behavior-incentivizing mechanism.

III. Information Theories and Intent to Infringe

A. Information-Forcing and Burden-Shifting Rules in IP Regimes

Ayres and Gertner articulate a foundational account of the efficiency of penalty-default rules in contract law, conditioning the enforceability of some contractual provisions on the disclosure of privately held information.[78] But a property regime that requires a showing from the claimant also has information-forcing characteristics.[79] For instance, requiring a showing of source significance is a penalty-default rule.[80] The validity of a mark depends on the mark owner providing information of source significance. That information is best generated by mark owner efforts to communicate the mark’s source significance to consumers and competitors. Evidence of effort to create source significance would be too expensive for most firms to generate, outside of a legitimate intent to advertise.

In addition to encouraging disclosure, information-forcing defaults can shape behavior.[81] For instance, basing the outcome in trademark infringement cases in part on commercial strength also has information-forcing benefits. Both validity of a descriptive signifier and robust protection in the market require a showing of strength in the market. This showing is difficult to make unless consumers see the mark as strong in a way that can be measured, or evidence of use of the mark over time leads a court to the same conclusion. And because the information to be disclosed is most likely to be generated when the mark owner follows a preferred course of behavior, a firm aiming to meet the disclosure requirement is more likely to engage in the desired behavior.

The bad faith inquiry likewise has an information-forcing effect. Bad faith use has an independent information value, communicating the newcomer’s willingness to impose costs on consumers to secure commercial advantage.[82] Modern trademark law’s development was guided in large part by English courts of equity in the nineteenth century.[83] Compared to courts of law, courts of equity applied what Smith calls “structured rules of thumb and shifting presumptions” that made traditional equity effective at policing loopholes and improving the rule of law.[84] Equity was empowered to police against advantage taking, and the continued focus on bad faith provides an opportunity to bring problematic inequitable behavior to light.[85]

B. Information Theory and Trademark Interference

Trademark law reduces communication costs for consumers by encouraging mark owners and newcomers to send credible signals of source and quality.[86] This information transmission function centers the consumer in the infringement analysis.[87] Trademark law is thus miscalibrated to the extent it ignores consumer perception; “Misalignment can allow market-distorting confusion to creep into the trademark ecosystem.”[88]

Some criticism of the intent inquiry stems from a suspicion that evidence of intent is used as an inaccurate proxy for likelihood of confusion, which should instead be established.[89] To correctly calibrate trademark protection, the law must account for how consumers receive messages from sellers in the marketplace.[90] A simplistic view of that frame might lead theorists to discount the importance of the seller’s intent in adopting its mark. But applying insights from Claude Shannon’s information theory to questions of intent in trademark infringement disputes provide a framework for understanding why ignoring evidence about the intentions of sellers in the market, whether owners or newcomers, would impose market distorting costs on consumers.[91]

1. An Information Theory of Communication Optimization

Information theory studies how to efficiently encode and transmit information.[92] Shannon’s foundational work explained the theoretical limits of communications technologies developed by AT&T in the 1940s, focusing on transmission issues in telephony.[93] Shannon conceived a simple model of communication to aid in responding to those communication challenges. An information source selects a message that is transmitted as a signal through a communication channel. The channel is the medium for the signal. A receiver translates the signal for the intended recipient at the message’s destination.[94]

Shannon’s work theorized how to optimize communication “when the signal is perturbed by various types of noise.”[95] Shannon’s theorem explains that the capacity of a communication channel is shaped by both the strength of the information-carrying signal and the amount of background noise or interference.[96] Interference in the communication channel can make it more difficult for the signal to reach its destination intact.[97] That noise imposes costs on the intended recipient.

To see how Shannon’s theory might reach less technical communication questions, consider a simple metaphor from Gus Hurwitz.[98] Channel capacity can be illustrated by imagining two individuals having a conversation in a crowded room. From the perspective of those individuals, the words they exchange are “signal” or desired communication. The words exchanged by others in the room are perceived as “noise,” extraneous information that makes the conversation more difficult to parse.[99] A speaker can compensate by speaking more slowly, which reduces the rate of communicated information and thus reduces channel capacity. The speaker may instead speak more loudly, but others in the room may react by increasing their own volume, increasing noise and decreasing channel capacity. Hurwitz’s metaphor illustrates how senders compete to communicate in a channel.[100] A surplus of messages may make it difficult, if not impossible, for a given message to get to its intended (or any) recipients.

2. Trademark Law and Information Theory

One can apply information theory to trademark law. As Deven Desai notes, the trademark is “the channel or medium through which a message is sent.”[101] Mark owners hope to send source and quality signals to consumers, who will use those signals to select the products they prefer and avoid the products they dislike.[102] One can imagine a quarrel-free trademark system where every seller can select an attractive and recognizable symbol to clearly distinguish their products from those of competing sellers. In reality, symbols are more limited.[103] Conflicts thus arise between mark owners and newcomers who use similar symbols to distinguish neighboring products.

A simplified information system with two competing sellers claiming use of the same symbol would resemble an interference channel. In an interference channel, two senders attempt to communicate to two receivers through the same channel.[104] The general problem is that with multiple senders and receivers trying to use the same channel, the interference may mean that the messages cannot be transmitted over the channel.[105] When multiple senders communicate through the same channel, the technical question is, “[w]hat limitations does interference among the senders put on the total rate of communication?”[106]

Interference increases errors in transmission.[107] As error increases, the effective channel capacity decreases.[108] Shannon notes that even an optimized channel can reach its capacity.[109]

Shannon himself was ambivalent about the value of noise compared to signal, and unconcerned with the semantic or meaning-bearing aspects of the message. Those issues were seen as “irrelevant to the engineering problem” addressed by information theory.[110] Indeed, noise is not the absence of information, or necessarily without value—it just happens to be information that the source did not desire to convey and/or that the destination would prefer not to receive.[111]

Scholars applying Shannon’s theories often focus on the costs and benefits of improving signal integrity. As Werbach observes, “The more likely it is that interference will be a practical problem, the more transaction costs we should tolerate to avoid it.”[112] Thus, Durham posits, “The best prospect for incorporating meaning into information theory is to adopt the recipient’s perspective, treating [noise or entropy] as a measure of the recipient’s uncertainty.”[113] The recipient is a “parameter” in defining information, as “all information should be regarded as information relative to a given observer.”[114]

If the recipient is the proper parameter by which to judge the utility of an information system, we must note that some in the purchasing population might prefer information that complicates the mark owner’s intended message. In Desai’s view, protecting trademarks as univocal limits “the ability for new options and new perspectives to reach the consumer.”[115] Desai criticizes the current structure of trademark law because it “assumes that the receiver is passive and either is not looking . . . or should not be looking for other signals. . . . Signals by competitors and consumers are treated as noise.”[116] Desai argues instead that trademark law should optimize the amount of information conveyed by a trademark, embracing “more of the new and unexpected.”[117] Consumers would, in this regime, face more uncertainty as competitors make more frequent unauthorized use of a given mark, but with the increased uncertainty comes increased information.[118] This additional information could serve as a knowledge spillover.[119]

That conception assumes the cost of interference (more information and therefore higher processing cost) is somewhat analogous to what Smith has described as the relatively costless “nuisance of being bothered by a message one does not want to hear.”[120] But as Smith notes, “where greater consequences attach to how a message is decoded, more intervention, public or private, is likely to occur” to require the sender of an unwanted message to internalize the cost.[121] Thus, “[m]ore information may not always be better, and additional information may add more than trivially to processing costs.”[122]

As Weaver observed, information and meaning might be connected and jointly restricted in a way “that condemns a person to the sacrifice of the one as he insists on having much of the other.”[123] In other words, as information increases, entropy increases, and intelligibility suffers.[124] With regard to the ability of consumers to receive reliable signals of source significance and quality assurances through the medium of a trademark, Heymann’s conception of consumer autonomy provides helpful guidance for how to meet consumer expectations: “Autonomy acknowledges that the interpretive process should be left as free from interference as possible; hence, it is appropriate that trademark law have some role to play in filtering out noise from competitors that incite[s] confusion as to source.”[125]

One therefore cannot assume that because noise provides some information, noise should be maximized. Indeed, the value of noise depends on whether one considers the system from the perspective of the sender, the receiver, or some other entity. For the recipient, more interference increases uncertainty.[126] This may be unfortunate for the recipient for whom, as Pierce notes, “the aim and outcome of communication” is often resolving uncertainty.[127] Thus, as Hazlett observes, the goal will not be minimizing interference, but instead optimizing it.[128]

Even when interference is undesirable, it is not necessarily fatal to communication. Indeed, as Carleial noted, even in the presence of strong interference signals, “it is theoretically possible to achieve the same [communication] rates that are achievable when interference is completely absent . . . because . . . it is possible for both receivers to estimate the interfering signal in a first decoding step, and then subtract it away.”[129] In other words, the greater the difference between the potentially interfering signals in the same channel, the easier it is for the receiver to sort between those signals.[130]

The trademark is a channel that possesses a homonymous structure. Multiple firms may use the same symbol for distinctly different goods, like DELTA for air travel and DELTA for faucets.[131] Where consumers can readily separate the offerings of one firm from those of another, Carleial’s observation holds; the apparent interference is potentially harmless because consumers can easily sort the messages.

But perfect interference creates absolute uncertainty and effectively eliminates channel capacity. Thus, the difficulty of sorting signal from interference increases when the trademarks are similar and the products proximate.[132] Information theorists often posit simple information systems where data is a series of binary units. If interference is perfect, then it will be equally likely that a received signal of 1 was actually 1 or was instead 0. If there is perfect interference and absolute uncertainty, the effective channel capacity is zero because the receiver cannot determine whether the sender intended to transmit the signal received.[133]

3. Intentional Interference and Bad Faith Infringement

Interference may be an incident of an overcrowded channel. But interference may instead be deliberate. For example, “[f]or many years, the government of the former Soviet Union jammed the Voice of America broadcasts so that its citizens wouldn’t hear news from the west.”[134] Intentional interference or deception is pursued “to conceal reality by inserting ‘noise’, or to mislead the decision-maker with biased information.”[135]

Kopp and coauthors posit an information-theoretic model of intentional interference. One strategy deployed by a sender hoping to deceive recipients is deception by corruption. The sender intentionally imitates or mimics an authentic message to create a false perception or false interpretation of the imitated message.[136] This “corruption” approach is cost sensitive. If gaining an advantage via corruption is costless, Kopp’s simulation demonstrates many players adopt corruption, displacing most other strategies.[137] But “[a]t higher costs, the population using the [c]orruption deception cannot gain a foothold in the population.”[138] To the extent this is generalizable, a successful policy response to the deployment of corruption deception is to increase the cost of the approach to make it unprofitable.[139] The profitability of deceptive behavior can be reduced by increasing the likelihood of detection, the consequences of detection, or both.[140] These intuitions can help us understand how judicial inquiries into bad faith can be optimized to improve the consumer search function of the trademark system, as discussed in the next part.

IV. Attuning the Intent Inquiry

If courts properly weigh evidence of a newcomer’s intent—good or bad—in selecting a mark, an inquiry into intent encourages defendants to engage in desirable behavior as competitors in an efficient market. An appropriately attuned intent inquiry should encourage newcomers to provide source-distinguishing information and limit source-confusing noise. But as discussed above, critics argue that the intent factor distorts the trademark confusion inquiry, in significant part because the newcomer’s intent is invisible to consumers and thus cannot influence their potential confusion.[141]

Shannon’s information theory—and its subsequent extensions—invite an accounting of whether confusing noise imposes greater costs on consumers seeking useful information in the market than the benefit it provides.[142] In other words, does the newcomer provide more clarifying signal, or more confusing noise? Certainly, intentionally “corrupting” the source-signaling function of a trademark should be discouraged. Intentionally imitating the mark of another to pass off its product as that of another is the key behavior a trademark system must prevent, if that system aspires to reduce consumer search costs and encourage sellers to invest in credible signals and maintain quality.[143]

But even reckless behavior is significantly more likely to cause confusion than careful or conscientious behavior, due to the very indifference of the reckless newcomer to the rights of others.[144] Often, courts find relatively little functional difference between willful blindness (knowledge but for the alleged infringer’s herculean efforts not to acquire it) and reckless disregard for the consequences of behavior. For instance, one appellate court correlates a reckless disregard for the mark owner’s rights or the possibility that it was willfully blind to the consequences of its infringement when assessing whether to grant an accounting of the newcomer’s profits.[145] Another appellate court finds “conduct deemed ‘objectively reckless’ measured against standards of reasonable behavior” would support disgorgement of profits, even if the newcomer lacked a “conscious awareness of wrongdoing.”[146]

The costs imposed by reckless indifference are apparent in Bambu Sales, Inc. v. Ozak Trading Inc.[147] In Bambu, the mark owner stopped selling its lighter cigarette rolling paper in the United States after American consumers complained. It arranged to sell the remaining stock in Nigeria, but some of that stock ended up in the hands of a U.S. reseller.[148] The reseller imported the branded paper but “took no steps to verify” its authenticity, never inquired whether the distributor was authorized to sell it, never asked where the distributor got the paper, never checked with the brand owner about whether the paper was genuine, and continued to sell it after the brand owner sued.[149] The court concluded that the reseller’s indifference was sufficient to support both disgorgement of profits and an award of attorneys’ fees.[150] Moreover, the reseller’s indifference led to consumer disappointment that would have been easy to prevent.[151] U.S. customers who purchased the paper from the reseller were disappointed in its quality and complained to the mark owner.[152] Behavior that indicates an indifference to the costs imposed on consumers is relevant to the likelihood of confusion analysis. Newcomers that generate more noise than signal externalize the cost of their entry not only on incumbent mark owners (about whom the law might reasonably be indifferent) but also on consumers (about whom the law ought not be indifferent).[153]

Optimizing interference requires figuring out what consumers as receivers need rather than how competing mark users interact. [154] Consider Coase’s famous analogy about the doctor’s office operating next door to a confectionery. As Werbach summarizes, “Any claim about interference can be expressed either in terms of transmitter intrusiveness or receiver sensitivity. We can choose to impose a duty on the transmitter, or we can impose a duty on the receiver, but either way, we make a choice.”[155] Those costs should not be borne by the mark owner who expends energy and capital clearly signifying source or the consumer seeking legitimate source-signifying information if those costs can reasonably be imposed on the bad faith or recklessly indifferent newcomer.

A system built to maximize information flow that requires the acquisition of a high degree of background knowledge can be costly for members of a large, anonymous, and heterogenous audience.[156] Smith argues that courts and policy makers hoping to limit confusion (which is critical when communicating high value claims to a broad audience) might be well advised to thus limit the amount of available information, limit reliance on special contexts, limit ambiguity, rely more on conventionalized meaning, and limit audience responsibility.[157] Smith notes that the information generators who do not face the audience’s full processing costs will skew toward “excessive extensiveness,” dumping more information than is welcome or necessary, and thus increasing the costs on the recipient.[158] Similarly, the bad faith trademark user is more likely than the good faith user to introduce confusing noise without counterbalancing source signals, imposing higher than necessary costs on consumers. This matters in part because attention resources of consumers are limited.[159]

If the plaintiff cannot open an inquiry into bad faith, it becomes difficult for the law to incentivize better behavior from competitors. Many of the behaviors considered in an analysis of intent indicate an indifference about, if not an intention to, create interference that courts should take seriously. For example, courts consider whether the newcomer knew about the plaintiff’s use, and what the newcomer did when it discovered that use.[160] It is difficult to prove the absence of knowledge of the owner’s use if the mark has a reasonable level of commercial strength. It is easier for the newcomer to show it engaged in relatively low-cost behavior, like conducting a trademark search, or following the advice of counsel about whether to enter the market.[161] These are behaviors the law should encourage if the goal is optimizing the interference consumers must manage.[162] An inquiry into intent can force that information to the surface.

Courts also consider whether the newcomer advertises in assessing intent.[163] Engaging with consumers and creating source significance distinct from that of the owner sends a signal that refutes an allegation of bad faith.[164] Other behaviors increase the signal-to-noise ratio when a newcomer adopts a mark that bears some similarity to the owner’s mark and uses it to sell proximate products. A market in which each entrant observed such standards would increase useful information for the average consumer, ceteris paribus.[165] Correctly calibrating the intent factor allows the trademark owner to raise the question of intent and invites the newcomer to disclose evidence of its trademark selection process. That information allows a court to assess whether the newcomer took care to minimize or recklessly exacerbated source-confusing noise in the market.[166]

The inquiry into whether a newcomer’s behavior evidenced bad faith, reckless disregard for, or willful blindness about prior trademark rights should be context sensitive, accounting for the size of the newcomer’s company and its expected expertise regarding the trademark owner’s business and rights.[167] The cost of acquiring that information is relevant to the inquiry, but assuming a trademark search is not prohibitively costly,[168] failure to conduct a reasonable search will indicate bad faith, willfulness, and/or reckless disregard toward the prior rights of others, even without knowledge of the plaintiff’s specific trademark.[169]

Even in cases like My-T Fine, in which an intent to benefit from similarity to the senior mark gives rise to a presumption of confusion, the presumption is rebuttable.[170] Thus, even at the extreme, bad faith intent has a burden-shifting, information-forcing effect.[171] The plaintiff must plausibly articulate the newcomer’s bad faith, which may be rebutted.[172] Furthermore, courts show sensitivity to the strength of the plaintiff’s mark and the similarity between the parties’ marks in deciding whether to apply the presumption. For example, in Gray v. Meijer, the court concluded in light of the weakness of the plaintiff’s mark and the low level of similarity, “[t]here was no ‘brand equity’” on which the defendant could capitalize. The defendant’s apparent bad faith was therefore irrelevant.[173]

Moreover, considering the newcomer’s intent in light of consumer needs must be sufficiently nuanced. Consumers are not one homogenous mass—different consumers have different levels of interest in disruptive entrants and different levels of tolerance for confusion.[174] Indeed, courts often consider whether consumers of a given category of goods are more or less likely to take care in making purchasing decisions.[175] Those more likely to take care are presumptively able to tolerate a higher level of interference caused by a newcomer’s potentially confusing use.

Consumers may refine their capacity to receive the signals they desire by fighting through a certain amount of noise. Yen proposes that consumers can be trained to be better receivers of trademark messages.[176] Tolerating a certain level of confusion in the marketplace may discipline consumers to be something other than the proverbial moron in a hurry.[177] Yen argues that consumers develop the ability to identify and distinguish between trademarks and receive and understand the subtle messages conveyed by trademarks by experiencing confusion.[178] Yen would thus limit trademark law to preventing confusion only “when the confusion is so serious that consumers probably will not straighten things out on their own . . . [and] meaningful disruption to markets is relatively likely.”[179] These considerations might reasonably inform the use of intent by courts in assessing whether confusion is likely.

Care must also be taken to ensure the collateral costs of forcing information about intent to infringe are not too high. One concern about information-forcing rules like the penalty-default rule is they can raise costs of transacting around or otherwise avoiding the penalty or the default to such a high level that those costs swallow up the benefit of disclosure.[180] In this spirit, Casagrande argues that allowing evidence of bad faith is problematic in part because it has a ratcheting effect—it benefits only the plaintiff.[181] Evidence of good faith has no commensurate benefit for the defendant in the likelihood of confusion analysis.[182] Thus, the plaintiff has every incentive to claim bad faith or willful infringement, even if it is not the case.[183]

If the inquiry into bad faith is costless for the mark owner but the discovery of bad faith drastically increases the chances of finding infringement, mark owners will always plead bad faith. I am not persuaded that courts systemically find bad faith when it is not present, or overweigh bad faith when it is found. But a policymaker so persuaded could fine-tune the inquiry by requiring mark owners to show more evidence before forcing the newcomer to counter the claim of bad faith. For instance, a court might analogize bad faith to fraud. A complaint must generally plead fraud “with particularity.”[184] Failure to meet this heightened pleading requirement may result in a court granting the defendant’s motion to dismiss.[185] A plaintiff will often be granted leave to amend, but if insufficient evidence of bad faith is proffered up front, the amended complaint should omit the bad faith claim at the peril of another dismissal.[186]

We could instead release the ratchet by crediting the newcomer when they conduct a reasonable search or otherwise signal their intent to distinguish their goods rather than their indifference to consumer confusion. Thus, if the intent inquiry reveals that the defendant engaged in reasonable behavior, they should be entitled to a moderating effect in their favor. For instance, communicative efforts like the prominent display of the newcomer’s distinct mark or the use of dissimilar trade dress indicate efforts by the newcomer to clearly signal source to consumers.[187] When a newcomer engages in good faith behavior, that behavior should, holding other things constant, be less likely to confuse consumers, and thus less likely to trigger liability. If courts granted such a good faith credit for alleged infringers, that practice might actually increase the information-forcing benefit of disclosing evidence of intent. At a minimum, crediting the newcomer for their good faith may prevent an inquiry into bad faith from uniformly benefitting mark owners. Moreover, if the law grants defendants greater leeway when they engage in the “good faith” behaviors likely to reduce consumer search costs, the market for mark-bearing goods will operate more efficiently as competitors respond to those incentives. In such a system, bad faith would expand potential defendant liability, but good faith would narrow it.

15 U.S.C. § 1052; 1 J. Thomas McCarthy, McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition § 11:2 (5th ed. 2024) (“No distinctiveness—no mark.”). Throughout this Article, I use “product” as a shorthand for goods or services.

See generally Alfred C. Yen, Intent and Trademark Infringement, 57 Ariz. L. Rev. 713 (2015); Mark Bartholomew, Trademark Morality, 55 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 85 (2013) [hereinafter Bartholomew, Trademark Morality]; Thomas L. Casagrande, A Verdict for Your Thoughts? Why an Accused Trademark Infringer’s Intent Has No Place in Likelihood of Confusion Analysis, 101 Trademark Rep. 1447 (2011).

Benkler refers to this as a “signal-to-interference” ratio. Yochai Benkler, Some Economics of Wireless Communications, 16 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 25, 41, 53 (2002). See also Jeanne C. Fromer, An Information Theory of Copyright Law, 64 Emory L.J. 71, 80–81 (2014) (“[N]oise in transmission can result from malfunctions in the message transmitter or from interference caused by noise or signals external to the transmitter.”).

15 U.S.C. §§ 1114, 1125.

15 U.S.C. §§ 1116, 1117.

See infra Section II.C.

See infra Section II.C.

15 U.S.C. § 1127 (“The term ‘trademark’ includes any word, name, symbol, or device . . . used by a person . . . to indicate the source of the goods . . . .”).

Fanciful, arbitrary, and suggestive marks are treated as inherently source signifying “on the theory that consumers who see a [symbol] that doesn’t describe the product will presume the [symbol] was meant to serve as a trademark and treat it like one.” Jake Linford, The False Dichotomy Between Suggestive and Descriptive Trademarks, 76 Ohio St. L.J. 1367, 1377 (2015) [hereinafter Linford, False Dichotomy]. See also CareFirst of Md., Inc. v. First Care, P.C., 434 F.3d 263, 269 (4th Cir. 2006) (“Measuring a mark’s conceptual or inherent strength focuses on the linguistic or graphical ‘peculiarity’ of the mark considered in relation to the product, service, or collective organization to which the mark attaches.” (quoting Perini Corp. v. Perini Constr., Inc., 915 F.2d 121, 124 (4th Cir.1990)). I use “signifier” as a shorthand for word, name, symbol, or device, following Barton Beebe, The Semiotic Analysis of Trademark Law, 51 UCLA L. Rev. 621, 633, 646 (2004).

2 McCarthy, supra note 1, § 16:4; Jake Linford, Are Trademarks Ever Fanciful?, 105 Geo. L.J. 731, 738 (2017).

2 McCarthy, supra note 1, § 15:30; 4 id. § 31:81.

2 id. § 15:30.

Id.; cf. Alexandra Jane Roberts, Mark Talk, 39 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L.J. 1001, 1011–12 (2021) (criticizing the simplistic nature of courts’ secondary meaning analysis, which has not evolved significantly since its conceptualization).

Jake Linford, Trademark Owner as Adverse Possessor: Productive Use and Property Acquisition, 63 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 703, 711, 718, 724–25 (2013) [hereinafter Linford, Adverse Possessor].

See, e.g., TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 29 (2001).

Trademark registration will be granted unless an examiner determines that the applied-for mark is not source signifying or otherwise falls within one of the bars under § 2 of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052.

See, e.g., Vidal v. Elster, 144 S. Ct. 1507, 1518 (2024) (“[T]rademarks developed historically to identify for consumers who sold the goods (the vendor) and who made the goods (the manufacturer).”); id. at 1521 (“Trademark protection ensures that consumers know the source of a product and can thus evaluate it based upon the manufacturer’s reputation and goodwill.”); id. at 1527 (Barrett, J., concurring in part) (“The law protects trademarks because they help consumers identify the goods that they intend to purchase and allow producers to ‘reap the financial rewards associated with the[ir] product’s good reputation.’” (quoting Jack Daniel’s Props., Inc. v. VIP Prods. LLC, 599 U.S. 140, 146 (2023))); see also id. at 1535 (Sotomayor, J., concurring) (arguing that trademark law’s purpose is “identifying and distinguishing goods for the public”).

Jake Linford, Valuing Residual Goodwill After Trademark Forfeiture, 93 Notre Dame L. Rev. 811, 819 (2017) [hereinafter Linford, Valuing].

Robert G. Bone, Enforcement Costs and Trademark Puzzles, 90 Va. L. Rev. 2099, 2116 (2004).

Robert G. Bone, Hunting Goodwill: A History of the Concept of Goodwill in Trademark Law, 86 B.U. L. Rev. 547, 549 (2006) [hereinafter Bone, Hunting Goodwill] (“The core of trademark law . . . is based on a[n] . . . ‘information transmission model.’ This model views trademarks as devices for communicating information to the market and sees the goal of trademark law as preventing others from using similar marks to deceive or confuse consumers.”).

Barton Beebe, An Empirical Study of the Multifactor Tests for Trademark Infringement, 94 Calif. L. Rev. 1581, 1589–90, 1592 (2006).

Id. at 1589–90. Beebe notes that, “Intent is not explicitly listed among the [Federal Circuit’s] DuPont factors. However, the Federal Circuit will consider it when it is relevant.” Id. at 1590 n.38.

Grayson O Co. v. Agadir Int’l LLC, 856 F.3d 307, 314–15 (4th Cir. 2017) (“If a mark lacks strength, a consumer is unlikely to associate the mark with a unique source and consequently will not confuse the allegedly infringing mark with the senior mark.”).

L. E. Waterman Co. v. Gordon, 72 F.2d 272, 273 (2d Cir. 1934) (“It would be hard, for example, for the seller of a steam shovel to find ground for complaint in the use of his trade-mark on a lipstick.”).

See Irina D. Manta, In Search of Validity: A New Model for the Content and Procedural Treatment of Trademark Infringement Surveys, 24 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L.J. 1027, 1036–37 (2007); cf. Jake Linford, Democratizing Access to Survey Evidence of Distinctiveness, in Research Handbook on Trademark Law Reform 225, 229–30 (Graeme B. Dinwoodie & Mark D. Janis eds., 2021) (asserting courts value survey evidence because it goes towards the mental perception held by consumers).

3 McCarthy, supra note 1, § 23:124.

See supra Section II.A.

See, e.g., Del Lab’ys, Inc. v. Alleghany Pharmacal Corp., 516 F. Supp. 777, 780 (S.D.N.Y. 1981); see also Linford, False Dichotomy, supra note 9, at 1374.

See, e.g., Coca-Cola Co. v. Gemini Rising, Inc., 346 F. Supp. 1183, 1187 n.1, 1189 n.7 (E.D.N.Y. 1972).

See Ian Ayres & Robert Gertner, Filling Gaps in Incomplete Contracts: An Economic Theory of Default Rules, 99 Yale L.J. 87, 97 (1989) (explaining that penalty defaults are contract rules that automatically penalize parties who fail to contract for something specific, which forces information sharing during the drafting process). Jeremy Sheff has argued that the dominant search cost account justifying trademark protection is an information-forcing narrative. Jeremy N. Sheff, Veblen Brands, 96 Minn. L. Rev. 769, 779 (2012).

See supra Section II.A.

See supra Section II.A.

See, e.g., Fortune Dynamic, Inc. v. Victoria’s Secret Stores Brand Mgmt., Inc., 618 F.3d 1025, 1032 (9th Cir. 2010) (“As a general matter, ‘[t]he more likely a mark is to be remembered and associated in the public mind with the mark’s owner, the greater protection the mark is accorded by trademark laws.’”); 1 McCarthy, supra note 1, § 11:73; 3 id. § 24:49. But see First Sav. Bank, F.S.B. v. First Bank Sys., Inc., 101 F.3d 645, 655 (10th Cir. 1996) (“When the primary term is weakly protected to begin with, minor alterations may effectively negate any confusing similarity between the two marks.”).

Ralph S. Brown, Jr., Advertising and the Public Interest: Legal Protection of Trade Symbols, 57 Yale L.J. 1165, 1203 (1948) (“[S]hoddy tactics on the part of defendants may have made many courts kinder to plaintiffs than the interests we have analyzed would require.”).

Beebe, supra note 21, at 1626–31; see also Yen, supra note 2, at 741 (“Even in cases that do not explicitly involve presumptions derived from intent, courts finding that a defendant intended to commit infringement almost always conclude that infringement occurred.”).

See Lionel Bently, The Place of Scienter in Trade Mark Infringement in Nineteenth Century England: The Fall and Rise of Millington v. Fox, 71 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 493, 521–23 (2020); Pamela Samuelson, John M. Golden & Mark P. Gergen, Recalibrating the Disgorgement Remedy in Intellectual Property Cases, 100 B.U. L. Rev. 1999, 2014 (2020).

. Restatement (Third) of Unfair Competition, § 22 cmt. b (Am. L. Inst. 1995); Mark Bartholomew, Advertising and the Transformation of Trademark Law, 38 N.M. L. Rev. 1, 9–10 (2008).

JL Beverage Co. v. Jim Beam Brands Co., 828 F.3d 1098, 1112 (9th Cir. 2016) (“‘[A]bsence of malice is no defense to trademark infringement.’ The relevant inquiry is not Jim Beam’s intent, but rather whether it adopted the colored lips logo with the knowledge that the mark already belonged to JL Beverage.” (citation omitted)). But see U.S. Polo Ass’n v. PRL USA Holdings, Inc., 800 F. Supp. 2d 515, 526 (S.D.N.Y. 2011) (citing as one of the Polaroid factors “the reciprocal of defendant’s good faith in adopting its own mark”), aff’d, 511 F. App’x 81 (2d Cir. 2013); 1A Anne Gilson LaLonde, Gilson on Trademarks § 5.09 (2024); 3 McCarthy, supra note 1, § 23:124; 4 Callmann on Unfair Competition, Trademarks and Monopolies § 21:87 (4th ed. 2024).

Tiffany & Co. v. Costco Wholesale Corp., 971 F.3d 74, 88 (2d Cir. 2020) (noting the defendant’s intent “to exploit the good will and reputation of [the plaintiff] by adopting the mark with the intent to sow confusion between the two companies’ products” drives an inference of likely confusion).

Fla. Int’l Univ. v. Fla. Nat’l Univ., 830 F.3d 1242, 1263 (11th Cir. 2016) (“If it can be shown that a defendant adopted a plaintiff’s mark with the intention of deriving a benefit from the plaintiff’s business reputation, this fact alone may be enough to justify the inference that there is confusing similarity.”); Min-Chiuan Wang, Reconstructing Trademark Infringement Damages from the Perspective of Option Theory, 19 J. High Tech. L. 192, 231 (2019).

Grey v. Campbell Soup Co., 650 F. Supp. 1166, 1173 (C.D. Cal. 1986) (citing, inter alia, AMF Inc. v. Sleekcraft Boats, 599 F.2d 341, 354 (9th Cir. 1979)), aff’d, 830 F.2d 197 (9th Cir. 1987).

See, e.g., Empresa Cubana Del Tabaco v. Culbro Corp., 70 U.S.P.Q.2d 1650, 1681 (2004).

Stone Creek, Inc. v. Omnia Italian Design, Inc., 875 F.3d 426, 436 (9th Cir. 2017).

Mark Bartholomew, Intellectual Property’s Lessons for Information Privacy, 92 Neb. L. Rev. 746, 777 (2014) [hereinafter Bartholomew, Lessons] (citing, inter alia, 15 U.S.C. § 1115(b)(4) (2006); Century 21 Real Estate Corp. v. Lendingtree, Inc., 425 F.3d 211, 225–26 (3d Cir. 2005)). See also Lendingtree, 425 F.3d at 243 (Fisher, J., dissenting) (“[T]he entire ‘nominative fair use’ defense asks whether the use was made with the intent to confuse.” (emphasis added)).

Bartholomew, Lessons, supra note 44, at 779.

Travis R. Wimberly & Guilio E. Yaquinto, The Infringer’s Mental State, Am. Bar Ass’n (June 30, 2021) (quoting Restatement (Third) of Unfair Competition § 22 cmt. c (1995)), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/publications/landslide-extra/infringer-mental-state/ [https://perma.cc/3RPV-28W8].

Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(d)(1)(A)(i); Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy, ICANN, § 4(b), https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/policy-2024-02-21-en [https://perma.cc/4CCE-8NBG] (last visited Sept. 3, 2024); see also Linford, Adverse Possessor, supra note 14, at 749.

Jason Scott Collection, Inc. v. Trendily Furniture, LLC, 68 F.4th 1203, 1223 (9th Cir. 2023) (attorneys’ fees are proper in exceptional cases of defendant’s “willful and brazen infringement”); Romag Fasteners, Inc. v. Fossil, Inc., 140 S. Ct. 1492, 1497 (2020) (Alito, J., concurring) (stating that while defendant’s bad faith or willfulness is no longer a requirement for disgorgement of profits, it is a critical factor); id. at 1498 (Sotomayor, J., concurring) (stating the same).

Globefill Inc. v. Element Spirits, Inc., No. 210-cv-02034-CBM (PLAx), 2017 WL 6520589, at *2 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 8, 2017).

David Berg, The Trial Lawyer: What It Takes to Win, Litigation, Fall 2018, at 18, 20.

See Globefill Inc. v. Elements Spirits, Inc., 640 F. App’x 682, 684 (9th Cir. 2016).

David Lat, Boutique Bests Biglaw in Booze-Bottle Battle, Above L. (Mar. 30, 2017, 3:33 PM), http://abovethelaw.com/2017/03/boutique-bests-biglaw-in-booze-bottle-battle/ [https://perma.cc/6KS4-4C2F] (summarizing the testimony).

Id.

See Jellibeans, Inc. v. Skating Clubs of Ga., Inc., 212 U.S.P.Q. 170, 176 (N.D. Ga. 1981), aff’d, 716 F.2d 833 (11th Cir. 1983) (“Since improper motive is rarely, if ever, admitted . . . , the court can only infer bad intent from the facts and circumstances in evidence.”).

See Innovation Ventures, LLC v. N2G Distrib., Inc., 763 F.3d 524, 529–30, 537 (6th Cir. 2014) (“A reasonable jury could have inferred” from the fact that defendants knew of plaintiff’s protected mark “that Defendants’ various marks were not used in good faith”; affirming jury verdict that 6 HOUR ENERGY, and other marks and uses, infringed 5 HOUR ENERGY and other marks and trade dress).

See TakeCare Corp. v. TakeCare of Oklahoma, Inc., 889 F.2d 955, 956–57 (10th Cir. 1989) (“[D]efendant’s continued use of the mark without explanation after notice . . . amounted to a wilful and deliberate infringement . . . .”); Tal S. Benschar, David A. Kalow & Milton Springut, Proving Willfulness in Trademark Counterfeiting Cases, 27 Colum. J.L. & Arts 121, 130 (2003) (“The classic evidence of willfulness is that a defendant continued to sell the same goods after being put on notice by the trademark owner that the goods are infringing.”). But see Estee Lauder, Inc. v. Gap, Inc., 932 F. Supp. 595, 615 (S.D.N.Y. 1996) (holding defendant’s refusal to “fold its tent” after learning of plaintiff’s similar mark did not constitute bad faith because defendant relied on attorney’s ultimately incorrect advice), rev’d on other grounds, 108 F.3d 1503 (2d Cir. 1997).

Compare Int’l Star Class Yacht Racing Ass’n v. Tommy Hilfiger, U.S.A., Inc., 80 F.3d 749, 753–54 (2d Cir. 1996) (“[The defendant’s] choice not to perform a full search under these circumstances reminds us of two of the famous trio of monkeys who, by covering their eyes and ears, neither saw nor heard any evil. Such willful ignorance should not provide a means by which Hilfiger can evade its obligations under trademark law.”), with Money Store v. Harriscorp Fin., Inc., 689 F.2d 666, 670–72 (7th Cir. 1982) (holding trademark applicant had no obligation to conduct a search into whether firms identified in a preliminary search were using the mark at issue in commerce), and Roger D. Blair & Thomas F. Cotter, An Economic Analysis of Damages Rules in Intellectual Property Law, 39 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1585, 1691 (1998) (“[A] rule requiring some level of search activity prior to commencing use of a mark makes more sense than does a rule absolutely excusing second users from any duty to investigate.”).

Menley & James Lab’ys Ltd. v. Approved Pharm. Corp., 438 F. Supp. 1061, 1067 (N.D.N.Y. 1977) (holding that evidence of intent to benefit from good will associated with senior user’s reputation “is especially convincing when the newcomer . . . has spent little or nothing at all in promoting its product”).

See Roberts, supra note 13, at 1006, 1011 and accompanying text.

See Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. Hunting World, Inc., 537 F.2d 4, 9 (2d Cir. 1976) (holding that generic terms “cannot [be] transform[ed] . . . into a subject for trademark”).

Jake Linford, A Linguistic Justification for Protecting “Generic” Trademarks, 17 Yale J.L. & Tech. 110, 121, 158 (2015) (citing TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23 (2001)).

See, e.g., Yankee Candle Co. v. Bridgewater Candle Co., 259 F.3d 25, 45 (1st Cir. 2001) (holding that evidence of intentional copying was not probative “[g]iven the highly functional nature” of the claimed elements).

Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. Haute Diggity Dog, LLC, 507 F.3d 252 (4th Cir. 2007) (“An intent to parody is not an intent to confuse the public.” (quoting Jordache Enters., Inc. v. Hogg Wyld, Ltd., 828 F.2d 1482, 1486 (10th Cir. 1987))).

Bartholomew, Trademark Morality, supra note 2, at 117, 122; see also Harvey S. Perlman, The Restatement of the Law of Unfair Competition: A Work in Progress, 80 Trademark Rep. 461, 472 (1990); Daryl Lim, Trademark Confusion Simplified: A New Framework for Multifactor Tests, 37 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 865, 923 (2022). For those who argue that trademark law should be less solicitous of consumer perception, or at least as solicitous of other normative interests, a consumer indifference critique of the intent factor would be unpersuasive. See, e.g., Mark Bartholomew, Navigating Trademark Law’s Empirical Turn, 62 Hous. L. Rev. 247, 260–63 (2024) (citing, inter alia, Christopher Buccafusco, Jonathan S. Masur & Mark P. McKenna, Competition and Congestion in Trademark Law, 102 Tex. L. Rev. 437, 442 (2024); Jeanne C. Fromer, Against Secondary Meaning, 98 Notre Dame L. Rev. 211, 214–15 (2022)).

Yen, supra note 2, at 725; cf. Jeremy N. Sheff, The (Boundedly) Rational Basis of Trademark Liability, 15 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 331, 352 (2007) [hereinafter Sheff, Rational] (“[R]ecent cases suggest that the defendant’s intent may be nothing more than an inferential link between similarity of marks and likelihood of confusion.”).

Yen, supra note 2, at 734, 736, 740, 743.

Robert G. Bone, Taking the Confusion Out of “Likelihood of Confusion”: Toward a More Sensible Approach to Trademark Infringement, 106 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1307, 1347–48 (2012).

Blake Tierney, Missing the Mark: The Misplaced Reliance on Intent in Modern Trademark Law, 19 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 229, 261 (2011); see John M. Murphy, The (Unfortunate) Significance of Intent in TTAB Proceedings Under Section 2(d) of the Lanham Act, 34 AIPLA Q.J. 177, 190 (2006).

Casagrande, supra note 2, at 1475.

See, e.g., Yen, supra note 2, at 736–38 (criticizing My-T Fine as a case where the court found that “intent alone” can support a finding of infringement).

My-T Fine Corp. v. Samuels, 69 F.2d 76, 77 (2d Cir. 1934).

Id. at 76–77.

Id. at 77 (“It would be impossible on this record to say that any one who meant to buy the plaintiff’s pudding has hitherto been misled into taking the defendants’ by mistake in the appearance of the box.”).

Id.

Id.

Id.

Yen, supra note 2, at 738.

Ayres & Gertner, supra note 30, at 94.

Lior Jacob Strahilevitz, The Right to Destroy, 114 Yale L.J. 781, 850 (2005) (proposing a limit on destructive instructions in wills that would require the owner to offer the public an opportunity to purchase a future interest in the property because a failure to reach the owner’s strike price would indicate they valued the property’s destruction more than anyone else valued its preservation); Ian Ayres, Ya-Huh: There Are and Should Be Penalty Defaults, 33 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 589, 598 (2006) (“[P]enalty defaults . . . block a legal status unless particularized information about specific dimensions [of the claimed rights] is adequately disclosed.”).

Linford, Adverse Possessor, supra note 14, at 731 (discussing the information-forcing value of a productive-use requirement in adverse possession cases); id. at 732 (discussing the information-forcing value of requiring mark owners to police their trademarks); Irina D. Manta, Bearing Down on Trademark Bullies, 22 Fordham Intell. Prop., Media & Ent. L.J. 853, 867–69 (2012) (proposing a penalty-default rule requiring the filing of demand letters with the PTO to discourage trademark bullying).

Cf. Nicholas Quinn Rosenkranz, Federal Rules of Statutory Interpretation, 115 Harv. L. Rev. 2085, 2146 (2002) (“[C]anons of statutory interpretation, like contract default rules, may be information-forcing. They also, however, may be accountability-forcing in a particular way.”).

Cf. Oren Bar-Gill & Omri Ben-Shahar, An Information Theory of Willful Breach, 107 Mich. L. Rev. 1479, 1491, 1499 (2009) (describing sanctionable willfulness in contract cases as “behaviors that reveal information about some underlying systemic pattern [of undetected value-skimming conduct], distinct from the breach itself.”).

Jake Linford, The Path of the Trademark Injunction, in Research Handbook on the Law & Economics of Trademark Law 403, 424–26 (Glynn S. Lunney Jr. ed., 2023).

Henry E. Smith, Property, Equity, and the Rule of Law, in Private Law and the Rule of Law 224, 233 (Lisa M. Austin & Dennis Klimchuk eds., 2014). As Smith describes them, morality and information costs are congruent if not coterminous. Bad faith is an important factor in part because it closes the loopholes too easily exploited in a system that is too rule-bound. Id. at 231. Considering bad faith is both information-forcing and consumer-protecting because it prevents exploitation that might be too subtle for consumers to detect.

Sheff, Rational, supra note 65, at 335 n.15, 358 & n.142. While Sheff discounts intent as a meaningful factor, he recognizes the relationship between confusion, blurring, and tarnishment constructs that echoes Henry Smith’s anti-advantage-taking rationale for equitable rules, “rationally cognizable proxies for the manipulations to which the non-rational cognitive processes triggered by trademarks are particularly susceptible.” Id. at 357–58. Sheff posits that courts’ use of proxy factors to set the boundaries of trademark liability essentially minimize the effect on consumers of non-rational biases errors “by proscribing and deterring the use of trademarks that cause such influence.” Id. at 373.

See supra Section II.A.

Bone, Hunting Goodwill, supra note 20, at 558.

Linford, Valuing, supra note 18, at 835; see also Mark Bartholomew, Cops, Robbers, and Search Engines: The Questionable Role of Criminal Law in Contributory Infringement Doctrine, 2009 BYU L. Rev. 783, 825 (“Trademark law is not calibrated necessarily to generate more trademarks, but it is designed to provide for an efficient marketplace that consumers can navigate as quickly and reliably as possible.”).

See supra notes 64–70 and accompanying text.

Jack P. Lipton, Note, Trademark Litigation: A New Look at the Use of Social Science Evidence, 29 Ariz. L. Rev. 639, 642 (1987) (“[C]ontemporary marketing and communication theory are both consistent with the notion that questions of trademark infringement and secondary meaning are based upon how the messages are interpreted by the consumer, not how they were intended to be interpreted by the producer.” (citing Walter Weiss, Effects of Mass Media on Communication, in 5 Handbook of Social Psychology 77 (Gardner Lindzey & Elliot Aronson eds., 3d ed. 1969))).

See Claude E. Shannon, Communication in the Presence of Noise, 37 Proc. Inst. Radio Eng’rs 10, 13 (1949) [hereinafter Shannon, Communication]; C. E. Shannon, A Mathematical Theory of Communication, 27 Bell Sys. Tech. J. 379, 407, 414 (1948) [hereinafter Shannon, Mathematical]; Warren Weaver, Recent Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Communication, in The Mathematical Theory of Communication 1, 17–19 (1964 ed. 1949). Other scholars have applied Shannon’s work to various intellectual property regimes, including Fromer, supra note 3, at 81–84, 87, 89–91 (copyright); Barton Beebe, An Empirical Study of U.S. Copyright Fair Use Opinions, 1978–2005, 156 U. Pa. L. Rev. 549, 596 & n.146 (2008) (discussing Martin Shapiro’s application of the communications theory in copyright law); David W. Opderbeck, Deconstructing Jefferson’s Candle: Towards a Critical Realist Approach to Cultural Environmentalism and Information Policy, 49 Jurimetrics 203, 222–23 (2009) (copyright); David W. Opderbeck, The Skeleton in the Hard Drive: Encryption and the Fifth Amendment, 70 Fla. L. Rev. 883, 909–10, 914–15 (2018) (copyright); Susan Scafidi, F.I.T.: Fashion as Information Technology, 59 Syracuse L. Rev. 69, 72–73, 79–80 (2008) (fashion); W. Michael Schuster, Information Theory and Patent Documents, 55 Akron L. Rev. 379, 381–85, 387–88 (2022) (patent claiming). But see Dan L. Burk, The Problem of Process in Biotechnology, 43 Hous. L. Rev. 561, 586–88 (2006) (critiquing the application of information theory to biotechnology patents).

Justin “Gus” Hurwitz, Madison and Shannon on Social Media, 3 Bus., Entrepreneurship & Tax L. Rev. 249, 259 (2019) [hereinafter Hurwitz, Madison].

Shannon, Mathematical, supra note 91, at 406–10; Justin “Gus” Hurwitz, Noisy Speech Externalities, 3 J. Free Speech L. 159, 162 (2023) [hereinafter Hurwitz, Noisy].

Shannon, Communication, supra note 91, at 10–11.

Id. at 10.

Hurwitz, Noisy, supra note 93, at 160–61, 163 (applying Shannon’s theory to free speech debates over social media).

Fromer, supra note 3, at 80.

Hurwitz, Madison, supra note 92, at 259–60; Hurwitz, Noisy, supra note 93, at 163.

Hurwitz, Madison, supra note 92, at 259–60; Hurwitz, Noisy, supra note 93, at 163; see also Thomas M. Cover & Joy A. Thomas, Elements of Information Theory 379 (1991) (“[I]n a cocktail party with m celebrants of power P in the presence of ambient noise N, the intended listener receives an unbounded amount of information as the number of people grows to infinity.”).

Hurwitz, Madison, supra note 92, at 259–60; Hurwitz, Noisy, supra note 93, at 163.

Deven R. Desai, Response: An Information Approach to Trademarks, 100 Geo. L.J. 2119, 2126 (2012).

Id.

Barton Beebe & Jeanne C. Fromer, Are We Running out of Trademarks? An Empirical Study of Trademark Depletion and Congestion, 131 Harv. L. Rev. 945, 948–49, 962, (2018).

Cover & Thomas, supra note 99, at 375; see also Randall A. Berry & David N.C. Tse, Shannon Meets Nash on the Interference Channel, 57 IEEE Transactions on Info. Theory 2821, 2821 (2011) (“The interference channel is the simplest communication scenario where multiple autonomous users compete for shared resources.”).

Cover & Thomas, supra note 99, at 374.

Id.

R.V.L. Hartley, Transmission of Information, 7 Bell Sys. Tech. J. 535, 535 (1928) (“[E]xternal interference, which can never be entirely eliminated in practice, always reduces the effectiveness of the system.”).

John R. Pierce, An Introduction to Information Theory: Symbols, Signals & Noise 156 (2d rev. ed. 1980).

Shannon, Communication, supra note 91, at 18 (“If the noise is increased over the value for which the system was designed, the frequency of errors increases very rapidly.”).

Shannon, Mathematical, supra note 91, at 379.

Alan L. Durham, Copyright and Information Theory: Toward an Alternative Model of “Authorship,” 2004 BYU L. Rev. 69, 80 (“[W]hen noise interferes with a message, disrupting its order in unpredictable ways, this actually adds information to the message rather than, as we would imagine, subtracting information.” (footnote omitted) (citing L. David Ritchie, Information 53–54 (Steven H. Chaffer ed., 1991))); Weaver, supra note 91, at 19 (“[I]f the uncertainty is increased [by the addition of noise], the information is increased, and this sounds as though the noise were beneficial!”).

Kevin Werbach, Supercommons: Toward a Unified Theory of Wireless Communication, 82 Tex. L. Rev. 863, 888, 890 (2004).

Durham, supra note 111, at 79–80, 88.

Guy Jumarie, Relative Information: Theories and Applications 62 (1990).

Desai, supra note 101, at 2124.

Id. at 2127 (footnote omitted); see also Mark P. McKenna, A Consumer Decision-Making Theory of Trademark Law, 98 Va. L. Rev. 67, 72 (2012) (arguing that trademark law should “focus on deceptive practices that interfere with consumers’ purchasing decisions”). For McKenna, the only “noise” trademark law should care about is noise sufficient to make consumers buy products they wouldn’t otherwise buy. Id.

Desai, supra note 101, at 2127.

Id. at 2125–27; cf. Elizabeth Townsend Gard & Sidne K. Gard, Fame: A Conversation About Copying, Borrowing, and Soup, 62 Hous. L. Rev. 367, 371 (discussing the relationship between fan borrowing and fame).

Brett M. Frischmann & Mark A. Lemley, Spillovers, 107 Colum. L. Rev. 257, 285 (2007).

See Henry E. Smith, The Language of Property: Form, Context, and Audience, 55 Stan. L. Rev. 1105, 1153 (2003).

Id.

Id. at 1140; see also Jake Linford, Copyright and Attention Scarcity, 42 Cardozo L. Rev. 143, 145 (2020) [hereinafter Linford, Copyright]; Weaver, supra note 91, at 27 (“[A] general theory [of communication] at all levels will surely have to take into account not only the capacity of the channel but also . . . the capacity of the audience. . . . [I]f you overcrowd the capacity of the audience you force a general and inescapable error and confusion.”).

Weaver, supra note 91, at 28; see also id. at 19 (while noise is information, “[s]ome of this information is spurious and undesirable and has been introduced via the noise. To get the useful information in the received signal we must subtract out the spurious portion”).

Durham, supra note 111, at 83; cf. Tribune Co. v. Oak Leaves Broad. Station, reprinted in 68 Cong. Rec. (Cook Cnty. Cir. Ct. 1926) 216, 219 (1926) (modifying injunction to prevent the defendant from “broadcasting over a wave length [sic] sufficiently near to the one used by the complainant so as to cause any material interference with the programs or announcements of the complainant over and from its broadcasting station”).

Laura A. Heymann, The Public’s Domain in Trademark Law: A First Amendment Theory of the Consumer, 43 Ga. L. Rev. 651, 694–95 (2009). Heymann counsels against extending ostensible protection of consumer autonomy to ensure against associations with the mark that the trademark owner would prefer to quash. Id. at 656–67.

Durham, supra note 111, at 85–87.

Pierce, supra note 108, at 79; see also Weaver, supra note 91, at 19 (“Uncertainty which arises by virtue of freedom of choice on the part of the sender is desirable uncertainty. Uncertainty which arises because of errors or because of the influence of noise is undesirable uncertainty.”).

Thomas W. Hazlett, The Wireless Craze, the Unlimited Bandwidth Myth, the Spectrum Auction Faux Pas, and the Punchline to Ronald Coase’s “Big Joke”: An Essay on Airwave Allocation Policy, 14 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 335, 374 (2001).

Aydano B. Carleial, Interference Channels, 24 IEEE Transactions on Info. Theory 60, 60, 69 (1978).

See also Cover & Thomas, supra note 99, at 403–07 (describing how a receiver might decode between two overlapping signals by treating the first sender’s signal as noise and decoding the second sender’s signal from the noise).

Jake Linford & Kyra Nelson, Trademark Fame and Corpus Linguistics, 45 Colum. J.L. & Arts 171, 194 (2022).

Cf. Hurwitz, Madison, supra note 92, at 258.

Pierce, supra note 108, at 126–28, 159; see also Hurwitz, Madison, supra note 92, at 250–80 (“[E]very communication channel has a theoretical maximum information carrying capacity and that once you exceed that capacity, meaningful signal (akin to “good” speech) becomes indistinguishable from noise (akin to “bad” speech).”).

Emory A. Griffin, A First Look at Communication Theory 52 (3d ed. 1997).

See Dongxu Li & Jose B. Cruz Jr., Information, Decision-Making and Deception in Games, 47 Decision Support Sys. 518, 518, 523–24 (2009) (effectiveness of deception in a zero-sum game requires one player to believe their observations are sufficiently accurate to make decisions and the other player possessing the ability to degrade those observations via deception).

Carlo Kopp, Kevin B. Korb & Bruce I. Mills, Information-Theoretic Models of Deception: Modelling Cooperation and Diffusion in Populations Exposed to “Fake News,” PLOS ONE (Nov. 28, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207383 [https://perma.cc/QE4L-GML3].

Id.

Id.

Id. (“[T]he cost to agents of performing . . . [c]orruption deceptions strongly determined persistence of populations benefiting from deception . . . .”); see also, e.g., Blair & Cotter, supra note 57, at 1644–45 (discussing optimal damages rules to discourage passing off).

Kopp, Korb & Mills, supra note 136.

See supra notes 64–70 and accompanying text.

See supra text accompanying notes 108–26.

See supra text accompanying notes 17–24.

Catherine M. Sharkey, Economic Analysis of Punitive Damages: Theory, Empirics, and Doctrine, in Research Handbook on the Economics of Torts 486, 489, 493 (Jennifer Arlen et al. eds., 2013) (describing a shift in tort law to grant punitive damages in cases where the defendant’s accidental conduct was committed recklessly).

4 Pillar Dynasty LLC v. New York & Co., 933 F.3d 202, 209–10 (2d Cir. 2019) (quoting Island Software & Comput. Serv., Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 413 F.3d 257, 263 (2d Cir. 2005)) (standard for willful copyright infringement); see also 4 McCarthy, supra note 1, § 30:62.

Fishman Transducers, Inc. v. Paul, 684 F.3d 187, 191 (1st Cir. 2012). But see W. Diversified Servs., Inc. v. Hyundai Motor Am., Inc., 427 F.3d 1269, 1273–74 (10th Cir. 2005) (“[A]n award of profits . . . is truly an extraordinary remedy and should be tightly cabined by principles of equity.”).

Bambu Sales, Inc. v. Ozak Trading Inc., 58 F.3d 849, 854 (2d Cir. 1995), abrogated by 4 Pillar Dynasty LLC., 933 F.3d 202 (effectively overruled on other grounds).

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id. at 851.

Id.

Similar concerns about legitimacy animate recent efforts by the Trademark Office to clear illegitimate registrations from the Principal Register. See Jeremy N. Sheff, An Empirical Evaluation of the Trademark Modernization Act, 62 Hous. L. Rev. 339, 344 (2024).

See Desai, supra note 101, at 2127.