I. Introduction

It was the mother of all broken political pledges. Having uttered “[r]ead my lips: [n]o new taxes” during the 1988 presidential campaign, President George H.W. Bush changed his mind two years later.[1] Facing growing budget deficits, harmful automatic spending cuts, and a threat of recession if the country’s financial problems were not addressed,[2] the Republican President struck a deal with Democratic Congress and signed the 1990 Budget Act, raising taxes on millions of Americans.[3] While the bottom half of earners got a tax cut, the top half saw their tax burdens rise by about two percent, with a hike three times that size for the very highest earners.[4] Bush paid for his statesmanship by losing the 1992 election, and the Republicans have not supported an increase in federal income taxes ever since.[5]

A year after Bill Clinton defeated Bush in the 1992 election, Democrats pushed through another broad-based tax increase.[6] While half of that 1993 tax increase came from the top few percent of earners, forty-six percent of taxpayers saw their taxes go up to some extent.[7] Tax hikes were unnecessary for the rest of the 1990s as budget deficits turned to surpluses.[8] Tax hikes were out of the question in the early aughts with the younger Bush in the White House.[9] And when the 2008 presidential election campaign arrived, it became clear that leading Democrats had a view of progressive taxation that was very different from the one their predecessors had fought for in the early 1990s.

Pressed by George Stephanopoulos during the Philadelphia debate, Hillary Clinton announced that she was “absolutely committed to not raising a single tax on middle-class Americans, people making less than $250,000.00 a year.”[10] Barack Obama upped the ante, proclaiming that he was “the first candidate in this race to specifically say [he] would cut their taxes.”[11] These promises to protect the “middle class” meant that even taxpayers in the top five (though not the top two) percent were protected from tax increases.[12] Raising taxes on the top half (as in 1990), the top third (as in 1993), or just the top ten percent of income earners was out of the question.

The Democratic Party today is not what it was in 2008. Influential Democratic politicians favor a scope of government redistribution in healthcare, immigration, and elsewhere “that would have been unimaginable for a Democratic candidate only a few years ago.”[13] Yet when it comes to taxes, a broad, 1990s-style view of tax progressivity is nowhere to be found. To the contrary, as a strong new wave of progressive politics entered the Democratic mainstream, the tax reform discussion shifted toward higher and higher taxes on fewer and fewer taxpayers, leaving everyone but the small cohort of Americans entirely off the hook. President Biden pledged not to raise taxes on anyone earning below $400,000,[14] which meant that his tax increases would affect at most the top two percent of earners.[15] Thresholds for many major tax increases actually proposed by leading Democratic politicians are much higher: $10 million in Representative Ocasio-Cortez’s plan[16] and one of President Biden’s proposals,[17] $32 million in Senator Sanders’s plan,[18] $50 million in a similar plan by Senator Warren,[19] and $100 million in separate reforms advanced by the Biden Administration[20] and Senator Wyden.[21] Given that an income of $2 million a year puts one near the top one-tenth of one percent of earners,[22] these proposals reveal an extremely narrow view of progressive tax reform.

This Article argues that this narrow view is mistaken for two related but independent reasons. First, this view severely limits the potential revenue of possible reforms. Granted, Congress can raise a lot of revenue from the rich—those in the top one percent or its upper fraction. But it can raise a lot more by also taxing those who are not quite rich but are not middle class either, in any plausible sense of the term. Given that the U.S. government now collects 3% less of Gross Domestic Product than it did two decades ago, limiting tax increases to the richest of the rich seems especially unwise.[23]

To be concrete—and relying on the wealth of data discussed in Part II—this Article argues that Congress should focus not only on the top one percent of earners but on the next nine as well—a group that this Article calls “the affluent.” The point is not that everyone within the top ten percent should face the same tax increase (they should not); the point is that both the rich and the affluent can and should contribute more to the cost of government.

The second reason to abandon a narrow view of progressive taxation and to embrace higher taxes on the affluent is the rise of inequality. Much has been written about that rise, and much of what has been written conceives of the problem as a growing gap between the one percent and everyone else.[24] That view, however, is seriously incomplete. Hidden in plain sight in publicly available data—yet inexplicably absent from public debate—is the startling fact that the affluent have done very well since the middle of the twentieth century—better, in a way, than most of the top one-percenters.[25] Trying to reverse the rise of high-end inequality by focusing on the rich while ignoring the affluent is to miss half the picture.

Parts II and III of this Article build the case for taxing the affluent. The case turns out to be surprisingly strong. The affluent are the only group whose income share has risen steadily since the end of World War II. Those with higher incomes saw much more volatility. Those with lower incomes saw only stagnation or decline.[26] Relatedly, the rise in the earnings gap between the college-educated (and, even more so, post-graduate-degree holders), and the rest is both greater in absolute terms and more consequential for the lives of most Americans than the rise of the top one percent.[27]

Looking at wealth inequality reinforces conclusions drawn from the analysis of incomes. Uncertain as they are, the latest wealth estimates suggest that even though wealth is extremely concentrated at the very top, the one-percenters have less of it than the affluent do.[28] Moreover, the rate of growth in average wealth of these two groups has been comparable in recent years.[29] At the same time, the affluent have more wealth than everyone below them in the wealth distribution combined.[30] Again, the affluent appear to be prime candidates for a tax increase.

A common justification for taxing the rich is that their staggering economic success is destroying the American Dream.[31] This is an argument about declining or stagnating economic mobility, possibly caused by a rising inequality in American society.[32] Yet it turns out that although a particular group of well-off individuals has indeed entrenched its economic advantage at the expense of everyone below, that group is not the one-percenters as is frequently argued, but rather the affluent.[33]

In addition to the evidence grounded in economics, there are powerful philosophical and cultural arguments that the dominant ethos of the affluent—meritocracy—is a not-so-subtle mechanism for perpetuating their advantage at the expense of everyone below.[34] Finally, turning to politics, many critics of inequality argue that the rich threaten American democracy.[35] Yet available evidence suggests that the affluent may well be as likely to bear the blame for capturing American politics as the rich are. Overall, given the affluent’s economic success, cultural dominance, and political influence, the case for higher taxes on the affluent is exceedingly strong.

Part IV turns from the reasons to tax the affluent to the ways of doing so. Raising income tax rates on that group is the most obvious solution, but it is neither the only nor the best option. One appealing alternative is to enact a carbon tax, which would be easy to design in a way that would combine environmental benefits with a top-ten-targeted tax increase. Another alternative is for the United States to finally join the rest of the world and enact a value-added tax while structuring it to concentrate its burden on the top ten percent—including both the rich and the affluent. The national income tax recently proposed by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman is yet another possibility.[36] Congress could also revise payroll taxes in a way that would place a greater burden on the affluent. Repealing certain tax expenditures would have a similar effect. None of these steps are mutually exclusive. Clearly, the problem with taxing the entire top ten percent is not a lack of tools.

Yet calls for taxing the affluent are almost entirely absent from political debate and public conversation. Legislative proposals of Democratic politicians aim only at the very top of the income distribution.[37] Likewise, reform-minded tax academics target the one-percenters or their upper crust either by relying on legislative proposals[38] or by offering no explanations at all.[39] On the few occasions when reformers do mention the affluent, it is to shield them from higher taxes.[40] The justifications offered, if any, are that the critical divide is between the one percent and everybody else,[41] and that taxes should not go up on the middle class.[42] The first justification does not withstand scrutiny based on available evidence, as Part II demonstrates; the second distorts the meaning of “middle class” beyond recognition.

In contrast with legislative proposals and with tax scholarship, critiques grounded in political philosophy and political economy do focus on the affluent and do mention tax reforms among many other ideas. But the tax reform discussions are brief, touch only on a few of the strategies discussed in Part IV, and are disconnected from the insights this Article extracts from the complex and growing empirical literature in economics and political science.[43] Overall, the literature offers no convincing reasons to give the affluent a tax pass while suggesting only occasional and cursory ideas for taxing the affluent.

Given this state of play, Part V considers the reasons why progressive tax reformers focus exclusively on the rich. The first reason that comes to mind is political expediency. The second relates to taxes that the affluent already pay. The third is about deference to expertise. And the fourth emphasizes large cost-of-living differences across the country. The Article responds to all these objections, concluding that some of them are weak and none are insurmountable. The affluent have stayed out of the tax policy conversation long enough. It is time to discuss, advocate, and eventually implement higher taxes on the top ten percent—both on the rich and on the affluent.

II. Meet the Affluent

Imagine that Congress decides that it needs to raise a lot of new revenue. Perhaps its predecessor enacted a trillion-dollar tax cut that did little to address the country’s pressing economic and social needs.[44] Or maybe an earlier Congress passed major legislation while severely underestimating its cost.[45] Or perhaps legislators become convinced that new spending programs are needed to redress the injustices that many earlier Congresses perpetrated and perpetuated,[46] or to put the net-zero emissions goal within reach,[47] or to offer meaningful assistance to workers displaced by globalization, automation, and AI proliferation,[48] or to protect elderly Americans from large cuts in benefits scheduled to happen in the not-so-distant future[49]—or perhaps all of the above! How would thoughtful and fair lawmakers go about this task?

A plausible answer is to look at the economic fortunes of various groups of Americans and see if some groups have done demonstrably better than others over some reasonable period of time. If these groups exist, they would be prime candidates for increased taxation. This part takes precisely this approach. The unexpected conclusion that emerges is that contrary to the dominant academic, political, and cultural narrative, those in the top one percent—individuals commonly referred to as the rich—have not been the only winners in the economic competition. The next nine percent—the affluent—have had plenty of success as well.

A. The Rich, the Affluent, and the Rest

Any search for major new sources of revenue begins at the top. After all, that is where the money is. The top is also where much of the country’s economic gains over the past half-century have ended up, leading to a drastic increase in inequality. Moreover, starting at the top is appealing because there is little doubt of what “the top” means . . . or so it seems.

The “[w]e are the 99 percent” slogan captured the popular imagination during the heyday of the Occupy Wall Street movement.[50] References to the “one percent” are now ubiquitous in the press and academic literature.[51] “There is a familiar story about rising inequality in the United States, and its stock characters are well known. The villains are the fossil-fueled plutocrat, the Wall Street fat cat, the callow tech bro, and the rest of the so-called top 1 percent,” wrote Matthew Stewart in a 2018 Atlantic essay.[52] A year later, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman (SZ, and together with Thomas Piketty, PSZ) reiterated in a book published on the eve of the 2020 presidential campaign: “[T]he main fault line in the American society is . . . between the 1% and everybody else.”[53]

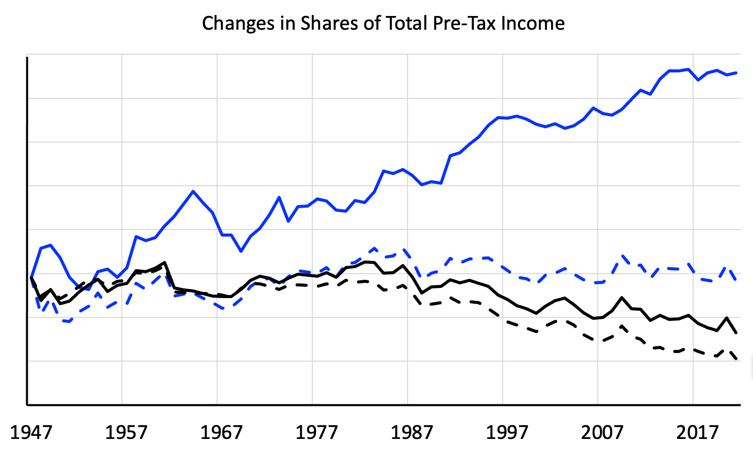

Yet the data—including the data meticulously assembled by PSZ themselves—tells a somewhat different story. Graphs in Figure 1 reflect PSZ’s most recent view of changes at the top of the U.S. income distribution.[54] Panel A shows income share trajectories over the entire period for which data is available for three groups: the top 0.1% (which this Article will call the “really rich”), the next 0.9% (the “pretty rich”), and the next 9% (the “affluent”).

For all three groups, income shares reveal a lot of volatility in the first half of the twentieth century. This fact is hardly surprising given that these decades featured a succession of dramatic and idiosyncratic periods: the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, and World War II. In the post-war era, income shares of the pretty rich and especially the really rich declined and then rose again while the income share of the affluent increased throughout the period. These observations suggest that we should pay some attention to the affluent.

Panel B shows why we should pay a lot of attention to that group. This panel depicts changes in income shares for those same three groups but with two key differences. First, Panel B covers only the post-war era, avoiding the idiosyncratic periods that preceded it. Second, the curves are shifted so that all three start at the same level in 1947.[55] The focus is on the changes from that point forward.

Looking at these changes reveals that the income share of the affluent has increased not only much more steadily than the shares of the other two groups but also by more than the rest. The income share of the really rich has fluctuated but now approaches that of the affluent. In contrast, the pretty rich—nine-tenths of the one-percenters—have not done nearly as well. Their income share both fluctuated and failed to increase past its 1947 level.

To be clear, Panel B does not suggest that the really rich and the affluent have done equally well. Their starting points were different. From those points, the really rich almost doubled their income share while the affluent saw “only” a 23% increase.[56] Nonetheless, in terms of the additional chunks of total income that each group captured (and other groups lost) in the post-war era, the affluent captured more.

Gerald Auten and David Splinter (AS) have a different take on the same data. Their well-known disagreement with PSZ is that once the proper adjustments to incomes and family units are made, the rise of the top one percent is not nearly as dramatic as what PSZ claim.[57] But it turns out that both AS and PSZ results reveal an important similarity—and one that has remained unacknowledged in the literature as far as I can tell. Their data, it turns out, tell us very similar stories about the economic fortunes of the really rich, the pretty rich, and the affluent.

Figure 2, Panel A is based on AS data and it shows income share changes for our three groups of interest from 1960 forward.[58] For comparison, Panel B shows PSZ data for the same groups and the same time period (rather than for the entire post-war era as in Figure 1, Panel B).

The graphs speak for themselves. Both AS and PSZ show that between 1960 and 2019, the really rich have done slightly better than the affluent while the pretty rich have lagged behind.

To complete the picture, we need to look not just above the affluent in the income distribution but below them as well. Figure 3 shows the changes in incomes shares of the affluent compared to the next three deciles from 1947 to 2021 based on PSZ data.[59]

The bottom line is clear: The affluent are indeed the only group other than the really rich whose economic fortunes have improved relative to everyone else since the middle of the twentieth century. Income shares of the pretty rich and those in the eighth decile are the same today as they were seventy years ago. And everyone else is doing worse than before.[60]

The implications of re-examining publicly available income inequality data with an eye toward the affluent are quite startling. If, instead of relying on conventional wisdom, one looks at the evidence on which that wisdom is based, conventional wisdom turns out to be seriously incomplete. Whether the goal is to reduce high-end inequality, raise a lot of new revenue, or both, it appears that the two groups to focus on should be the really rich and the affluent. The really rich would make the list because they experienced the most dramatic relative increase in their income share in recent decades. The affluent would make it because they have seen the steadiest increase in their fortunes and the largest increase in their income share throughout the post-war era.

Needless to say, this conclusion is very preliminary. The discussion so far has focused only on changes in income shares. After all, it was these changes, reported by Piketty and Saez (PS) in their seminal 2003 paper, that started the contemporary debate about inequality and redistribution.[61] Yet changes in income shares are just one way of measuring both incomes and inequality. Changes in wealth, economic opportunity, and political influence are among other important factors. The affluent, it turns out, are major sources of tax revenue and significant contributors to the growth of inequality by all these other measures as well.

B. Who Are These People?

Percentile thresholds are precise but abstract. Dollar thresholds are easier to grasp. And professions and career paths offer an even richer understanding. So who, exactly, are the affluent? And how do they differ from the one-percenters—the pretty rich and the really rich?

There are many ways of setting income thresholds for each of these three groups. The easiest one is to look at Adjusted Gross Incomes (AGI) reported by the Internal Revenue Service.[62] But millions of Americans do not file tax returns, so the AGI thresholds are surely too high.[63] Two alternatives preferred by economists are (a lower and less comprehensive) fiscal income and (a higher and more comprehensive) imputed national income.[64] Looking at all three measures, rounding, and adjusting for inflation,[65] a reasonable estimate is that today, the top 10% income threshold is about $150,000, the top 1% threshold is about $500,000, and the top 0.1% threshold is about $2 million.[66]

What do these numbers mean? With earnings between $500,000 and $2 million a year, the pretty rich make enough to guarantee what people in this group often call “comfortable” lives.[67] Successful lawyers, doctors, engineers, software developers, mid-level executives, and even some academics in select fields all belong to this group, especially if they are members of two-earner households.[68] These workers are quite different from top executives, successful business owners, and superstar lawyers and doctors, as well as real estate and finance professionals who belong to the really rich category.[69]

At the same time, many of the affluent look nothing like the top earners just mentioned. Associates at large law firms and Wall Street banks, doctors in just about any general practice, and even some UPS drivers are all in the affluent ranks.[70] There are, of course, many other members of this group, as the later discussion emphasizes.[71] Perhaps it is this group’s great heterogeneity that lies at the heart of persistent confusion about how to define this group and even how to call it.

Some monikers are quite creative. There are HENRYs—high earnings not rich yet—that apparently include the 95–99th percentiles of the income distribution.[72] Howard Gleckman calls the same group “merely rich.”[73] Saez refers to “upper-middle-income families and individuals (up to the top 1 percent threshold[)].”[74] Saez and Zucman define those in the 90–99th percentiles as “upper middle class.”[75] Richard Reeves uses the term “upper middle class” to refer to those in the 80–99th percentiles of the income distribution, calling them “dream hoarders” as well as the “affluent.”[76] Hoarders or not, calling someone in the 98th percentile “middle income” (Saez) or “middle class” (Saez and Zucman, as well as Reeves), even with an “upper” attached, is more than a little Lake-Wobegonian.[77]

Americans’ views about where the boundaries lie reflect similar confusion. Asked by Pew Research Center whether they belong to the “upper class, upper-middle class, middle class, lower-middle class, or lower class,” only one to two percent of respondents picked the first category. About fifteen percent—from the eighty-third to ninety-seventh percentile of respondents—chose upper-middle class.[78] Among respondents to the 2018 General Social Survey with incomes above $150,000 (surely placing every respondent in the top ten percent of the income distribution in that year), only sixteen percent identified themselves as the “upper class,” sixty-four percent called themselves “middle class,” and nineteen percent thought that they belonged to the “working class.”[79] The clear takeaway is that there is no generally accepted category describing people who are neither rich nor in the middle—not in academic discourse, not in political debates, and not in common imagination.

This conceptual and definitional ambiguity both reflects a problem and creates one. It reflects a lack of clarity about an important group that has succeeded in the American economy over the past seven decades. This lack of clarity, in turn, makes it very difficult to have a coherent discussion about redistribution from this group. It is hard to decide how to tax people without knowing who they are!

Yet the affluent clearly are a group that deserves special attention. Incomes between $150,000 and $500,000 may not seem particularly high to those who earn them, but these incomes do delineate a cohort that has had significantly more economic success than everyone below it. This observation is true if we look at income shares, as we have already seen. It will be true for other indicators of economic and non-economic success as well.

III. Why Tax the Affluent

It is a bit surprising that even today, after two decades of vigorous inquiry into income inequality and a heated public debate on the subject,[80] an important part of the inequality story is missing from the picture. The economic success of the affluent that leaps from the page when looking at Figures 2 and 3 has not been recognized until now. This “forgetting of the affluent” is even more surprising because the pivotal PS paper that kick-started the contemporary inequality debate paid attention to the top ten percent and not just the top one.[81] Yet over time, these scholars’ focus shifted decisively toward the one-percenters and their upper decile (the really rich), leaving the affluent mostly out of the picture.[82] Cultural and political discourse followed the same trajectory.[83] The contribution of the affluent to income inequality—and their revenue potential—faded into obscurity.

Part II offers what a lawyer may call a prima facie case for taxing the affluent. But it is too early to conclude that the affluent—as well as the rich—should pay higher taxes. There are important economic indicators other than income shares that need to be considered. Political power and cultural prowess are important as well. The task of this part is to dig further into the data in order to see if additional reasons—other than changes in income shares highlighted in Part II—support higher taxes on the affluent.

A. Who Earned All the Extra Income?

Having considered changes in income shares in detail in Part II, we begin by taking another look at incomes. Incomes are obviously important for arguments about income tax reform. But there are more ways of evaluating incomes than by looking at changes in income shares.

To start, what if we look at changes in incomes rather than income shares? We would find, as David Autor explains, that the affluent have had great success in the modern economy while those below them have not.

[C]onsider the earnings gap between a college-educated two-earner husband-wife family and a high school-educated two-earner husband-wife family, which rose by $27,951 between 1979 and 2012 (from $30,298 to $58,249). This increase in the earnings gap between the typical college-educated and high school-educated household earnings levels is four times as large as the redistribution that has notionally occurred from the bottom 99% to the top 1% of households. What this simple calculation suggests is that the growth of skill differentials among the “other 99 percent” is arguably even more consequential than the rise of the 1% for the welfare of most citizens.[84]

Data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) paint a similar picture. While the average salary of the top quintile of earners grew by 58% since 1979, the average salary of the same group—excluding the top one percent—grew by 44%. Thus, most of the growth in the average salary came from those below the top one percent.[85] At the same time, the rate of wage growth has not been the same throughout the distribution. Even though wages have grown for everyone except the bottom quintile of men, they grew noticeably faster for the top ten percent.[86]

Looking at the totals rather than the averages reinforces this takeaway. “Between 1979 and 2013, the top 1 percent saw a jump of $1.4 trillion in pretax income, while those between the eighty-first and ninety-ninth percentiles saw a gain of $2.7 trillion.”[87] Clearly, there is a lot more income to redistribute downward if one looks below the one-percent threshold and not only above it. If we wanted to share all recent income gains more broadly, surely the affluent should do some sharing.

Moreover, inequality of annual incomes described in Figures 1–3 reveals an incomplete picture. To take an extreme example, none of those in the top one percent of the income distribution last year may be among the one-percenters today. If so, a growth in the top-one-percent income share between 2022 and 2023 would clearly not mean that rich people circa 2022 got even richer. The turnover of individuals falling into any part of the distribution depends on economic mobility.[88] The important point to recognize here is that lifetime incomes—rather than incomes in any particular year—are the key to truly understanding income inequality.

Studying lifetime earnings is challenging because one needs to know entire earning histories of millions of workers over decades. Recent research overcomes these data challenges and offers important new insights into lifetime earnings inequality.[89] It turns out that something happened to lifetime earnings in the mid-1960s. Cohorts entering workforce before 1967 saw robust earnings growth, with the top one percent doing much better than the rest and the affluent doing only slightly better than everyone else.[90] But after 1967, earnings stopped growing for just about everyone, except for the top ten percent. For that fortunate group, not only did lifetime earnings keep growing during post-1967 decades, but the rate of growth for some of the affluent exceeded the rate for the one-percenters.[91] If anything, lifetime earnings data offers an even stronger reason to tax the affluent than the cross-sectional data presented in Figures 1–3 and typically used to support the arguments for higher taxes on the rich.[92]

The implications of this discussion are unmistakable. Whether one focuses on the magnitudes of income gains over time or on changes in lifetime earnings, the affluent cannot be ignored. Rejecting higher taxes on that group would leave a lot of revenue on the table—more revenue, in fact, than all the revenue available by restricting redistribution to the one-percenters.[93] So whether the goal is to generate new funding for much-needed government programs, or to redistribute from those who have done particularly well in the past decades, income data shows that redistribution from the affluent should surely be part of the conversation.

B. Who Got Rich?

Turning from incomes to wealth, it must be acknowledged that wealth estimates are even more speculative than income estimates.[94] But given the importance of wealth inequality and the herculean efforts to estimate it by multiple research teams, we now consider wealth estimates with an eye toward the affluent.

The most recent numbers come from SZ;[95] Matthew Smith, Owen Zidar, and Eric Zwick (SZZ);[96] a team of Federal Reserve economists;[97] the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT);[98] and the CBO.[99] The overall trajectories of changes in wealth concentration and the current wealth shares are fairly similar for all estimates. All show an increase in the wealth share of the top one percent from the late 1970s and a decrease in the wealth share of the bottom ninety percent over roughly the same period.[100] The wealth share of the affluent declined between the late 1970s and late 1980s and has barely changed since.[101] So over the past three decades, the one-percenters got richer, the affluent held their own, and everyone else lost ground.[102] As for today, all research teams report that the affluent as a group hold more wealth than the one-percenters as a group—either slightly or significantly.[103] The affluent also hold more than twice the amount of wealth than the decile immediately below.[104]

Turning from wealth shares to wealth growth rates yields similar conclusions. From the turn of the century, the average wealth of the affluent and the one-percenters both grew briskly while everyone else lagged behind.[105] So whether one looks at wealth shares or absolute wealth growth, the affluent have done well. Their wealth as a group exceeds that of the one-percenters and is also greater than the combined wealth of everyone else. If one seriously considered taxing wealth, excluding the affluent would shrink the plausible tax base by more than half.

Of course, the affluent are nine times more numerous than the one-percenters are. So the individual wealth of the affluent has not grown as much as that of the one-percenters. And the taxes the affluent pay should not grow as much either. But leaving the affluent out of the conversation about new revenue sources altogether amounts to a position that their taxes should not grow at all. That position is difficult to sustain given the great—and growing—wealth of the affluent.

C. Who Ruined the American Dream?

Almost all income and wealth inequality studies come with a major caveat: they measure trajectories of incomes and wealth, not people. A finding that the income share of the top one percent doubled in ten years may reflect, in the extreme, a situation where none of the one-percenters in year one remain in the top percentile in year ten. The opposite would be true in a society with very low mobility where the elites are entrenched and perpetuate their status by passing it on to their children. If America happens to be such a society, the key question for our purposes is who causes low (or declining) mobility, and, in particular, whether the affluent are part of the problem.

1. Intra-Generational Mobility. Familiar reference to skyrocketing inequality and the rise of the one percent evoke a mental image of a privileged group of rich people whose incomes rise higher and higher, leaving everyone else behind. That mental image, however, is wrong. Membership in the top one percent is quite fleeting. It is the affluent who have succeeded in staying above the rest.

Intra-generational mobility “shows how the income of households changed over time relative to the incomes of other households.”[106] Using tax return information with data on the highest earners,[107] researchers studying intra-generational mobility discovered that the share of households remaining in the top one percent from year to year drops in half after just two years and falls to somewhere between a third and a quarter after five.[108] One-percenters drop out of the one percent with surprising regularity. The top ten percent group is significantly more stable. For example, six out of ten members of that group in 1996 remained in it throughout the following decade. Moreover, the 1996 one-percenters who fell out of their elite group by 2005 ended up mostly among the affluent.[109] At the same time, over a ten-year period, “as many as 10 percent of the population have at least 1 year in the top 1 percent.”[110]

The implication is clear. If we wanted to redistribute from well-off people whose incomes reach the top one percent at some point, increasing taxes on incomes in the top one percent would yield only sporadic and limited redistribution. Higher taxes on incomes on the top ten percent, in contrast, would do the job quite well.

Changes in mobility are as important as its levels are. Overall, mobility has changed little since the 1990s.[111] But there was a decline in downward mobility at the top—and not just any decline:

[T]he percentage of households in the top income quintile that remained there increased from roughly 62 [to] 69 percent even though the percentage remaining in the top 1 percent stayed the same. . . . [Moreover,] the percentages of households remaining in the top income groups increased from 56 [to] 62 percent for the top 10 percent and from 51 [to] 54 percent for the top 5 percent. Thus, the decrease in downward mobility occurred for all but the top 1 percent of households.[112]

The affluent, it turns out, have been particularly successful in entrenching their economic advantage—more successful, in fact, than the one-percenters. So the best available evidence we have today suggests that the affluent—as well as those in the next decile[113]—appear to be primarily “responsible” for the decline in relative intra-generational mobility.

This claim of “responsibility” is not a causal one—it is an observation of a purely mechanical relationship. The affluent did something to arrange their economic affairs in such a way that more and more of them have kept their incomes in the top ten percent of the distribution. As a matter of arithmetic, this success necessarily means that others have been having an increasingly hard time becoming affluent themselves. What is the causal explanation? The rising educational premium mentioned earlier is part of the story—but only a part of it.[114] There are less benign reasons as well, as we will see later on.

2. Inter-Generational Mobility. In contrast with intra-generational mobility, which tracks movement up and down the income ladder during one’s lifetime, inter-generational mobility reveals the extent to which parents’ incomes determine those of their children.[115] The best-known fact about inter-generational mobility is what Alan Krueger famously dubbed the Great Gatsby Curve.[116] There is a very strong correlation between mobility and inequality, with the United States occupying an unenviable position of having high inequality and low mobility. Krueger’s (and many others’) interpretation of the Great Gatsby curve was that high inequality causes low mobility.[117] Given the precipitous rise of the one percent, Krueger predicted a twenty-percent drop in inter-generational mobility in the United States.[118]

But that drop never happened. A careful study of millions of tax returns reveals the reason for Krueger’s misprediction:

[T]here is little correlation between mobility and extreme upper tail inequality—as measured e.g., by top 1 percent income shares. . . . Instead, the correlation between inequality and mobility is driven primarily by “middle class” inequality, which can be measured for example by the Gini coefficient among the bottom 99 percent.[119]

Setting aside the reference to the bottom 99% as “middle class,” these findings point squarely to the affluent. They are the only group (other than the one-percenters) whose income share rose throughout the decades after World War II.[120] So if higher inequality does indeed undermine inter-generational mobility, it is the rise of the affluent—rather than the one-percenters or anyone below the affluent in the income distribution—that likely lies at the heart of the problem.

Another study bolsters this conclusion. Comparing a stark difference in inter-generational mobility between two similar countries—the United States and Canada—Miles Corak discovered that this difference arises in a very particular way. Overall, U.S. mobility is about half that of Canada.[121] But this difference “has little to do with the degree of mobility of children raised by families in broad swaths of the middle part of the distribution . . . [rather, it] is at the extremes of the distribution that the two countries differ.”[122] At the upper end, it is the difference in inter-generational mobility of the top ten percent of earners that sets the two countries apart.[123] Americans born into the top decile stay in the top decile.[124]

The best evidence about intra- and inter-generational mobility paints a picture all-too-familiar by now. Yet again, the affluent are key to the growth of inequality. Yet again, they reveal themselves as solid sources of tax revenue. Their incomes are much more stable compared to the one-percenters. The turnover among the affluent is much lower than among the one-percenters. Overall downward mobility at the top decreased, and the decrease points clearly at the retrenchment of the affluent. By any measure, they appear to have played a key role in stagnation and decline of social mobility in the United States.

This conclusion is not to be taken lightly. A conviction that hard work will bring success is a core part of the American Dream.[125] A belief in that dream “turns out to be a key determinant of support for redistribution.”[126] And that support determines the broad outlines of the social welfare state.[127] If any social group makes the American Dream increasingly remote—as the affluent appear to do—higher taxes on that group should be given serious consideration.

D. Who Sapped the American Spirit?

Until now, the discussion has focused on objective economic characteristics. But the size of one’s paycheck is not the only thing that matters to people. The dominant ethos of the affluent, several incisive thinkers explain, is as much of a problem as the rise of their bank accounts.

Michael Sandel’s recent book is an excellent—and by no means only—example of this critique.[128] Sandel argues that over the past half-century, American liberals, including most of the Democratic Party establishment, have made progress toward dismantling America’s old social structure based on wealth, race, gender, and family connections. They have replaced this old structure, Sandel explains, with a new system based on merit—a regime where anyone “who work[s] hard and play[s] by the rules deserve[s] to rise as far as their talents and dreams will take them.”[129]

But this seemingly egalitarian and optimistic slogan turned out to have devastating implications for those who fail to advance very far in a meritocratic society. Losers in meritocratic competition have no one to blame but themselves. They have no talents, they made wrong choices, and no matter how hard they try for the rest of their lives, they are condemned to meager existence in the shadow of meritorious winners looking down at the losers “with disdain.”[130] The result of this “tyranny of merit” is a set of widespread and deep “grievances [that] are not only economic but also moral and cultural; they are not only about wages and jobs but also about social esteem.”[131] Sandel emphasizes that “[c]onstruing populist protest [arising from these grievances] as either malevolent or misdirected absolves governing elites of responsibility for creating the conditions that have eroded the dignity of work and left many feeling disrespected and disempowered.”[132]

Importantly for our purposes, Sandel is very clear about who these governing elites are. They are “the comfortable classes” who “live in affluence,” “the credentialed, professional classes,” “managerial-professional classes,” and, specifically, “the wealthiest 10 percent.”[133]

Sandel’s critique is hardly a voice in the wilderness. Daniel Markovits offers a similar assessment, with an emphasis on the misery that meritocratic competition has brought to its “winners.”[134] Matthew Stewart attributes America’s current social predicament to the combined efforts of the affluent and the pretty rich.[135] These two groups, Stewart argues, have entrenched their economic advantage while making themselves feel good about their progressive ideology.[136] The Democratic Party, he warns pithily, is becoming “a home for an affluent, educated elite that seeks to correct every form of injustice except the inequality that is the actual basis of its privilege.”[137] David Brooks agrees.[138]

Richard Reeves sees the same problem coming from the same source: the professionals with six-figure incomes, college degrees, and pensions funds, or, as he calls them, “dream hoarders.”[139] Without joining Sandel in condemning meritocracy wholesale, Reeves argues that our society is not meritocratic in practice. The affluent use the system to their and their children’s advantage while hypocritically claiming adherence to high ideals.[140]

Sandel, Markovits, Stewart, Reeves, and Brooks do not construct models, run regressions, or rely on computational algorithms. But their critiques are biting and persuasive. The affluent have been successful, and they have found ways to entrench and pass their success to their children. But beyond these economic realities, the affluent have also developed a cultural narrative that is not only self-justifying but—key point—demeaning to many of those whose economic fortunes look increasingly dreadful. Because the affluent dominate the media, this message reaches a wide audience indeed. And even though many Americans ignore mainstream media altogether, they get a second-hand version of the same message—with dialed-up condescension and diminished empathy—from Fox News.[141]

Overall, then, if we turn from economic to cultural and social, it is very hard to excuse the affluent from the responsibility for America’s current ills. Quite likely, the affluent have more to do with sapping the American spirit than any other income group. When combined with the findings about their role in reducing economic mobility as well as their income and wealth, it is obvious that trying to reverse the rise of high-end inequality by focusing on the rich while ignoring the affluent is to miss half the picture.

E. Who Dominates American Politics?

Finally, there is politics. Concerns about economic power translating into political power, which then reinforces economic power and so on, are not new.[142] The one-percenters, or their upper crust, are always at the center of these concerns.[143] Rich people rule! proclaims a Washington Post article written by leading political scientist Larry Bartels.[144] The United States is an oligarchy, not a democracy, claim BBC and Vox.[145] High-end inequality, leading tax scholar Daniel Shaviro points out, “may lead to plutocratic capture of the political system by the super-rich, enabling them to extract rents and greatly reduce the system’s responsiveness to all others’ interests.”[146] Yet rigorous evidence supporting these claims is sparse, and whatever evidence there is points to the affluent as well as the rich.

“For decades, most political scientists have sidestepped [the inquiry into how economic power shapes American politics], because it has not seemed amenable to rigorous (meaning quantitative) scientific investigation.”[147] Things started to change with publication of influential books by Bartels[148] and Martin Gilens,[149] and especially a subsequent paper based on the data collected for one of these books.[150] Working with the most comprehensive dataset of policy preferences ever assembled,[151] Gilens and Benjamin Page concluded that “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.”[152]

But who exactly are these “economic elites”? Gilens and Page cannot answer this question. Preferences of the “economic elites” that they study are the estimated—not actual—preferences of individuals with incomes “at the ninetieth percentile point (the middle of the top 20 percent of respondents).”[153] Following the title of Gilens’ book, Gilens and Page call this group “the affluent.”[154] So what Gilens and Page actually find is that estimated preferences of individuals at the 90th percentile point have a significant influence on U.S. politics, while estimated preferences of those lower in the distribution (specifically, at the 50th and the 10th percentile points) do not.[155] Gilens and Page are clear that the question of “exactly which economic elites (the ‘merely affluent’? the top 1 percent? the top one-tenth of 1 percent?) have how much impact upon public policy, and to what ends they wield their influence” remains unanswered.[156]

Research on preferences of political donors further questions conventional wisdom about who drives American politics. Adam Bonica and colleagues measured ideological skew of four groups of donors to political campaigns: the affluent plus the upper middle class, the one-percenters, multi-millionaires, and multi-billionaires.[157]

Perhaps surprisingly, researchers found that as the income of contributors grows, political polarization declines. Billionaires, it turns out, fund less extreme political causes than Fortune 500 executives, who in turn are less polarized than the top 0.01% of donors, who are less partisan than “small donors” are.[158] Given that many of “small donors” are likely to be affluent, these findings suggest that the affluent may be significant contributors to America’s political polarization.[159]

The ability to influence policy is surely a major political power. But it is not the only one. Political scientists talk about two other faces of power: to set policy agenda and to shape the public opinion.[160] When it comes to these powers, the role of the affluent is undeniable. As Reeves points out:

Pretty much every position in the influencing business is in fact filled by a member of the upper middle class [(by which Reeves means 80–99th percentile of the income distribution)]: journalism, academia, research, science, advertising, polling, publishing, the media (old and new), and the arts are, almost by definition, upper middle class strongholds.[161]

The same is true of the large and influential think tank and policy advocacy industries.[162] And, of course, there are government representatives: members of the U.S. Congress,[163] the Vice President,[164] executive department heads and their high-level subordinates,[165] all of whom are compensated at a level that puts them squarely into the affluent camp. Any serious attempt to constrain the power of a particular group to influence agenda setting and opinion shaping should clearly pay close attention to the affluent.[166]

This part has considered the most recent research in economics and political science to ask a new question: what does this research tell us about the affluent? The results are unexpected. It seems almost self-evident that rich people rule; that the highest income earners are the cause of the growing inequality; and that they are to blame for the demise of the American Dream, for America’s social malaise, and for the country’s political polarization. But as this part makes clear, all of these intuitive assertions are probably wrong if interpreted to mean that only the one-percenters are the culprits.

The affluent are major contributors to the U.S. income and wealth inequality. Quite possibly, they are the main obstacles to higher social mobility. Most likely, they are also primarily responsible for sapping America’s spirit. And arguably, they may be influencing American politics more than any other group.

These findings are hardly common knowledge. Research discussed in this part generally focuses on the top one percent or its upper decile. One needs to sieve through the pages, the graphs, and the numbers—or to generate the numbers oneself based on reported results—to evaluate the contribution of the affluent to the phenomena discussed here. So there are reasons why this evaluation has not been done until now. But the data is there, and the overall takeaway cannot be clearer: whether one searches for sources of new revenue, aims to counter the rise of high-end inequality, or both, there are plenty of reasons to raise taxes on the affluent.

IV. How to Tax the Affluent

With so much focus on the rich, it stands to reason that there are several specific proposals for raising their taxes. These include much higher marginal rates,[167] novel mark-to-market taxes,[168] higher Social Security taxes,[169] higher estate taxes,[170] and numerous versions of a wealth tax,[171] among other suggestions.[172] Because the affluent have been mostly ignored, one may surmise that the options for taxing them are much more limited. This part shows that such a conclusion is unwarranted. Not only are there multiple ways of raising taxes on the affluent, but several plausible alternatives come with a bonus of advancing other worthwhile goals. The resulting double-benefits make higher taxes on the affluent even more appealing.

A. A Carbon Tax

Glaciers are melting, forests are burning, and temperature records are broken every time one checks the news.[173] Tackling global warming is an urgent need, and a carbon tax (or an analogous emission trading scheme) is the best way of doing so.[174] Unfortunately, a carbon tax is regressive—it places a greater burden on lower-income households. As a share of their incomes, these households spend more to fill their gas tanks, heat or cool their homes, and pay for food and clothing, all of which would become more expensive if a carbon tax were introduced, at least for some time.[175] The solution to this regressivity problem is well known. A carbon tax would raise a lot of revenue. If some of it is returned to lower-income households, the overall effect of the tax may turn from regressive to progressive.[176]

This so-called carbon dividend (or rebate) is the most redistributive but not the most efficient use of carbon tax revenue.[177] So existing research focuses on limited rebates sufficient to protect only those struggling to get by.[178] Economists also tend to model the simplest possible dividend—a lump sum payment to everyone.[179] Yet none of these choices are intrinsic to the carbon dividend idea. It is entirely plausible to design a carbon tax-plus-dividend in such a way that most of its burden would fall only on the top ten percent of earners or a group only slightly larger in size.

No research appears to consider this idea, but existing scholarship and government statistics do offer estimates that make this idea realistic. According to one estimate, a $30 per ton of CO2 tax—a price very close to the price of CO2 reflected in the currently operating European emissions trading scheme[180]—would raise enough revenue to keep welfare of the bottom four income quintiles (80%) constant and even protect the lower portion of the top quintile from any loss.[181] A different study using the U.S. Treasury Distribution Model finds that multiple refund mechanisms may restrict the burden of a carbon tax to the top one or two deciles.[182] Yet another recent modeling exercise reaches a similar conclusion.[183]

Moreover, all these estimates are based on the carbon tax rate that is woefully inadequate to save the planet. Rather than $20–$50 per ton of CO2 assumed in these studies, the tax rate would need to be set above $200 per ton to fully offset the social cost of carbon and keep the temperature from rising by more than 2.5 degrees Celsius.[184] If (or, more likely, when) the climate catastrophe becomes scary enough for most voters to finally embrace drastic measures, a carbon tax at around $200 per ton of CO2—or even half as high—would surely produce enough revenue to generate a dividend that would protect everyone outside of the top ten percent from economic loss, with plenty of revenue left to invest in green technologies or other pressing social needs.[185]

Finally, there is no need to reinvent the wheel in terms of the specific carbon dividend design. A refundable income tax credit that phases out with income would do the job.[186] This credit is the same kind as the one that Congress enacted to stimulate the economy in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.[187] A carbon tax supplemented with this kind of tax credit is the best means of achieving both the revenue and the distributional goals advanced in this Article while tackling global warming as well.

B. A Progressive VAT Reform

A value-added tax (VAT) is a consumption tax adopted by 168 countries around the world, but not by the United States.[188] “A VAT operates much like a national sales tax, but is collected at all stages of production rather than just from retailers.”[189] So, for example, if it takes five steps to make and sell a paper clip—from mining iron ore to smelting it, extruding iron wire, cutting and shaping it, and selling the product at a convenience store—and if each step is performed by a different business, a VAT would be imposed in five incremental steps on the value added in each. A VAT has two major advantages over a sales tax. First, a VAT is more difficult to evade because it is imposed incrementally while a sales tax is typically imposed at a single point of retail sale. Second, in some situations, multiple sales taxes are imposed on the same value added, leading to major over-taxation.[190] This issue never arises with a VAT because VAT taxpayers further down the production chain get credit for VAT taxes paid earlier in the same chain.[191] Overall, a VAT is both efficient and effective in collecting large amounts of revenue. It is efficient because by virtue of being a tax on consumption, it does not distort the choice between consuming and saving as the income tax does.[192] It is effective because it is more difficult to evade than both the sales tax and the income tax.[193]

Yet both the Republicans and the Democrats have reservations about a VAT. Republicans are concerned that it is a money machine.[194] A VAT is indeed an extremely potent revenue-raising tool.[195] Moreover, because a VAT is an indirect tax (consumers experience it as a relatively small addition to a sales price rather than a large lump sum they see on their annual tax returns), it is easier for governments to nudge the VAT rate up bit by bit.

Democrats are reluctant to support a VAT because it is regressive.[196] Enacting a VAT would raise after-tax prices of goods and services.[197] Lower-income people spend a greater share of their incomes on purchasing both, so a basic VAT is indeed regressive. But there is no doubt that a reform package with a VAT at its center may be structured to blunt or even reverse its regressivity. In fact, the resulting distributional burden may fall largely on the top ten percent. Two recent proposals with detailed revenue and distributional estimates performed by the country’s leading experts strongly support this conclusion.[198] And there are known ways of making a VAT progressive even without additional reforms.[199]

Along with a carbon tax, a VAT is the most promising way of addressing both revenue and distributional concerns animating this Article. Less than a decade ago, the Republican Speaker of the House and the chair of the House tax-writing committee advanced a tax very similar to a VAT in Congress.[200] The effort failed, but the chance of the ultimate VAT enactment increased. Both a VAT and a carbon tax offer additional benefits.[201] A carbon tax tackles the climate crisis. A VAT raises revenue in the least distortionary way.[202] Among policy alternatives for taxing the top ten percent, a carbon tax and a VAT are at the top of the list.

C. A Payroll Tax Reform

The United States imposes a 12.4% payroll tax on all wages up to $168,600.[203] Revenue raised by this tax is used to fund Social Security payments.[204] Though nominally half of the tax is paid by the employee and another half by the employer, economists agree that employees bear all or most of the tax burden.[205]

Because the $168,000 wage ceiling is at the lower edge of the top-ten-percent range, removing the ceiling is an obvious way of raising taxes on the top ten percent. Yet neither President Biden nor President Obama has supported this policy.[206] As we have already seen, both Presidents pledged to limit tax increases of any kind to the top one or two percent of earners.[207] Repealing the wage ceiling only for the top one- or two-percenters would be the exact opposite of what this Article advocates.

A repeal of the wage ceiling for everyone above it would amount to a very significant tax hike. For a two-earner couple with taxable income in the core of the affluent income range, the marginal federal income tax rate is currently 24%.[208] Uncapping the payroll tax would amount to a fifty percent rise in that couple’s marginal tax rate.[209] Whether an increase of this magnitude is necessary or not, it is important to keep in mind that a payroll tax reform is not an all-or-nothing proposition. If a 12.4 percentage point tax increase on the affluent is too large, wages above the current cap but below $500,000 (the top-one-percent threshold) may be taxed at a lower rate (6%, to take one example), with the rate returning to 12.4% for incomes above the half-a-million threshold. More gradual increases and different thresholds can easily be put in place. Clearly, adjusting the payroll tax is a simple way to increase the tax burden of the affluent.

D. A New National Income Tax

We now turn from three taxes that are well-understood and widely implemented to a tax that has been proposed very recently and has received little attention. At the very end of their book dedicated to arguments supporting much higher taxes on the rich, in the space of four pages, Saez and Zucman (SZ) introduce a very different idea: a national income tax (NIT).[210] While its name echoes familiar terms like the National Football League, “national” in the name of the tax does not refer to its all-American nature. Rather, the proposed tax is a tax on what economists call “national income”[211]—the estimate of all income generated in a country during a year, whether that income is in cash or takes the form of in-kind transfers, currently taxable or not.[212]

The NIT would be imposed at a flat rate (SZ suggest 6%) on all incomes with exceptions only for depreciation, U.S. dividends, retirement distributions, and government transfers.[213] There would be no other deductions or exemptions and no tax-exempt organization. A simple way to implement this tax, SZ explain, would be to tax all labor income in a way similar to a payroll tax in existence today; to tax all business profits with no deductions (other than depreciation), and to tax all interest income earned by individuals.[214] At the same time, and in contrast with a VAT, government transfers such as unemployment benefits and government assistance to the poor would be exempt.[215] Just as with a VAT, the NIT would be imposed in addition to the existing individual and corporate income taxes.[216]

SZ argue that the NIT is the twenty-first century version of a VAT: it is an equally powerful money machine but without problematic distributional consequences.[217] If a VAT-based reform package can raise billions of dollars while concentrating its burden on the top ten percent,[218] a similar NIT-based reform package surely can as well. Granted, NIT is a very new idea that SZ describe only in very general terms. But at least at first glance, NIT offers yet another alternative for raising taxes on the affluent.[219]

E. Raising Rates and Eliminating Tax Expenditures

Given the possibilities already discussed, it should be clear that raising taxes on the affluent may be accomplished in many different ways. Yet even more alternatives are available. One obvious reform is to raise their marginal tax rate. As just mentioned, many affluent taxpayers face the top rate of 24%[220]—not exactly a staggering number. There is surely some room for a rate increase. This step would raise the tax burden of the affluent in the most obvious way, so it may be the most difficult to implement politically. It would also be a less efficient increase than a VAT or a carbon tax. But in principle, a rate increase should be on the table along with other measures.

Another alternative is to repeal or significantly limit the generosity of so-called tax expenditures—special provisions allowing various tax reductions (deductions, credits, exclusions, and rate cuts) that a comprehensive income tax would not allow. The mortgage interest deduction, the charitable deduction, and the state and local tax deduction are just a few well-known examples.[221] The revenue loss from tax expenditures is large (over a trillion dollars a year), and their distributional consequences are mostly regressive.[222] Some of these expenditures benefit mostly the rich[223] but many benefit the affluent a great deal.[224] Repealing some or all of these expenditures would raise the tax burden of the affluent while reducing distortions in the existing income tax structure.[225]

F. The Beginnings of a Case for Taxing the Affluent

It is important to note that some of the proposals made here build on earlier ones. For whatever reason, most of these earlier proposals—tentative and brief as they may be—come neither from tax law experts nor from public finance economists.[226] Instead, they come from thinkers who took a broad look at America’s economic and social predicament and saw that the rise of the rich is not the only problem.

Yet Sandel, Markovitz, and Reeves—scholars who considered tax policy changes in response to the rise of the affluent—did not advance their tax arguments far. Sandel’s policy solutions aiming to shift the country from the “tyranny of merit” to the “common good” focused primarily on the education and labor policy.[227] His discussion of taxes was brief and limited to the call for lower payroll taxes and higher consumption taxes.[228] Markovits recommended uncapping the Social Security tax to promote middle-class work.[229] Because tax policy was not his focus, he spent little time on the economic analysis of his proposal or on considering the magnitude of the proposed tax hike.[230] Reeves considered taxes only at the very end and only in passing. He urged limiting tax expenditures by either converting them into refundable tax credits or capping the deduction rate.[231] The effect of such a cap would barely burden the affluent.[232] Reeves also emphasizes that the affluent should accept paying “a slightly higher tax bill,” and that the costs of extra taxes “will be small.”[233]

Sandel, Markovits, and Reeves hold the affluent responsible for many of the current cultural, social and economic ills. They suggest various non-tax reforms and they all mention taxes. But they do not develop and defend the case for raising taxes on the affluent as well as the rich.

This part makes clear that if the affluent continue to remain outside of the tax reform debate, it would not be for a lack of policy options to change the status quo. A range of alternative policies would increase the tax burden of the affluent while raising revenue and achieving other important goals. There are also plenty of reasons to implement such reforms, as Parts II and III explain. So why have the affluent stayed out of the mainstream tax reform conversation? It is time to consider objections to taxing the entire ten percent rather than just the top one.

V. Objections

Objections to higher taxes on the affluent are easy to imagine—so easy, in fact, that it is surprising that none of them have been explicitly articulated in the literature. At least some of these objections appear insurmountable when initially raised. This part argues that none are. The case for higher taxes on the affluent remains strong.

A. Is This All About Politics?

The first—and most obvious—reason to exclude the affluent from any tax increase conversation is politics. It is important to raise taxes on the really rich (and possibly the pretty rich), but one needs the support of the affluent to do so. Agitating for higher taxes on the affluent would undermine their support, making any progressive tax reform less likely.[234] Ergo, give the affluent a pass.

Yet political constraints are not a satisfactory explanation. If the past decade has taught us anything, it is that one should be very careful making arguments about political constraints. Think back to 2014. Few people thought that Donald J. Trump would become a U.S. President, yet he did.[235] Nor did it occur to anyone that major 2016 presidential candidates in both parties would oppose a signature free trade agreement being finalized by the Obama administration, yet they did.[236] Running for President while calling oneself a socialist was a sure way to make oneself irrelevant—until it wasn’t.[237] And supporting efforts to overturn a presidential election was unthinkable (one hopes!) for over a century, yet a large segment of today’s Republican Party supports just that.[238]

Going back to the “[r]ead my lips: [n]o new taxes” pledge, President Bush’s foremost reason to break it was a growing budget deficit.[239] H. Ross Perot captured 19% of the popular vote in the 1992 presidential election by styling himself as the only candidate who could get both debt and the deficit under control.[240] The national debt at the time was under 45% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[241] If someone predicted in 1991 that the debt would balloon to 100% of GDP, federal government tax collections as percent of GDP would shrink,[242] yet politicians would not view the situation as a national emergency, the forecaster would be laughed out of the room. Yet that is exactly where the country stands today.[243] Whatever seems politically impossible today may become entirely possible tomorrow.

It would be also quite ironic if those favoring higher taxes on the rich were to dismiss higher taxes on the affluent as unrealistic. Proponents of higher taxes on the rich often emphasize that these taxes are possible because they would be nothing new. The top marginal tax rate was 70% or higher until the early 1980s, they remind us.[244] One needs no further proof that a rate much higher than the current 37% is realistic today.[245]

But the same (and even stronger) argument may be made about higher taxes on the affluent. This Article started with an example of two significant tax reforms—one in 1990 and another in 1993—that raised taxes on groups even larger than the top ten percent.[246] Moreover, while the pre-1980-high top marginal rate applied to very few individuals,[247] the 1990 and 1993 tax hikes applied to hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of taxpayers.[248] These tax hikes are also more recent than the 70% top marginal rate. If history tells us that higher taxes on the rich are possible, it has the same message about higher taxes on the affluent.

Furthermore, whatever weight the point about political constraints carries when it comes to legislative proposals is shed when it comes to academic discourse. Realism is not the primary coin of the academic realm. Tax scholarship is full of interesting new ideas that are wholly unrealistic. Tax rate setting by an administrative agency,[249] indexing the tax code to prevent increases in inequality,[250] and enacting a global wealth tax[251] are all wholly implausible in practice, as their authors well understood.[252] Yet lack of realism did not—and should not—stop scholars from taking these ideas seriously. By comparison, tax increases on the affluent are not only plausible but familiar from not-too-distant history. Recall that both President Bush and President Clinton raised taxes on the affluent in the 1990s.[253] They are surely realistic enough to merit a serious discussion by academics.

It would be silly to ignore political constraints when talking about taxes. These constraints exist, and they surely make it easier to raise taxes on the top one percent than the top ten. But this difference does not mean that higher taxes on the affluent are impossible or even implausible. And it certainly does not justify shying away from making a conceptual case supporting them.

B. Are the Affluent Taxed Too Much Already?

One may reasonably think that the argument about raising taxes on a particular group should address taxes that this group already pays. This section explains why this is not necessarily so. In any case, higher taxes on the affluent make a lot of sense whether one views their current tax burden as relevant or not.

Part II articulated multiple reasons for taxing the affluent more. Most of these reasons relied on concepts that are unaffected by the taxes that the affluent pay today. Mobility studies are based on pre-tax incomes.[254] Wealth inequality reflects a lot of wealth created through the accumulation of untaxed capital gains.[255] Arguments about democracy and meritocracy are not tied to any specific income concept. Whatever tax burdens the affluent face today, lessons learned in Part II remain unchanged.

Turning to these tax burdens does nothing to suggest that the affluent are overtaxed. Figure 4 shows changes in average tax rates (and, therefore, overall tax burdens) of the affluent compared to the top one percent and the bottom ten for comparison.

Clearly, the average rates of the affluent changed little over the entire period for which the data are available. Yet their pre-tax incomes grew steadily over the same period, leading the affluent to capture a greater additional income share than nine-tenths of the top one percent (the pretty rich)[257] while everyone else’s income shares stagnated or declined.[258] Note that the next highest decile faces essentially the same rate today as it faced sixty years ago, just as the affluent do. Yet a look at Figure 3 reveals dramatic differences in pre-tax income trajectories between these two groups. The affluent may feel overtaxed, but evidence points in the opposite direction.

C. Follow the Experts?

If neither politics nor current tax burdens justify giving the affluent a tax pass, what about deference to expertise? If serious thinkers and tax policy experts believe that the affluent should not be taxed more, they must have good reasons for their views. This section considers what these reasons may be and how convincing they are.

1. The One Percent Divide in Theory and Data. The strongest set of arguments for taxing the rich—and only the rich—comes from Piketty, Saez, and Zucman. Their arguments—made at different points in time and with various collaborators—fall into two buckets: arguments based primarily on data, and arguments based primarily on theory.[259]

There is no need to spend much time on data-based arguments here. Part II addresses most of them. Recall that Saez and Zucman emphatically state that “the main fault line in the American society is . . . between the 1% and everybody else.”[260] Yet a look at each data-based argument they make—changes in income inequality, wealth inequality, social mobility, and democratic accountability—reveals that every reason they offer for raising taxes on the rich applies to the affluent. Saez and Zucman’s additional point—about much higher marginal tax rates faced by the rich before the 1980s in contrast with roughly unchanged marginal tax rates faced by the affluent[261]—loses much of its bite if we return to Figure 4 while keeping in mind that average rather than marginal tax rates measure the tax burden.[262] In sum, digging into the data while paying attention to both the top one percent and the next nine reveals clear reasons to raises taxes on both.

Turning to theory, two influential articles explain why the rich should pay higher taxes. The first is by Saez and Peter Diamond.[263] These distinguished economists conclude that the marginal tax rate on the one-percenters should be 73%, reaching this conclusion in three steps. First, they explain that while the income threshold for the top one percent (converting their numbers into 2023 dollars) is about $590,000,[264] the average income in that group is almost exactly $2 million.[265] Second, they point out that based on the standard assumptions of the optimal tax theory, the marginal utility of a person earning $2 million is less than four percent of that of an average earner.[266] Finally, given this stark difference, they conclude that the marginal utility of the one-percenters may be disregarded completely, so the optimal revenue-maximizing rate is 73%.[267]

Diamond and Saez’s paper is influential,[268] but its main conclusion has several significant weaknesses. To start, the three-step argument just summarized involves a bit of a misdirection. The conclusion that utility is zero for an average earner in the top one percent is not at all the same as the conclusion that this utility is zero for all earners in that group. Income corresponding to an almost-zero marginal utility, Diamond and Saez explain, is $2 million.[269] But this figure is the threshold not for the top one percent but for the top 0.1%. Whatever misgivings one may have about equating the marginal utility of 140,000 or so really rich households (top 0.1%) to zero, one would be hard-pressed to do the same for the 1.4 million households in the top one percent.[270] So whatever Diamond and Saez’s calculation tells us about taxing the top 0.1%—and it does not tell us that much as we are about to see—it offers no reasons to tax the top 1% as a whole differently from the top 10%, whether one thinks that the one-percenters’ taxes should go up or not.[271]

Moreover, Diamond and Saez’s argument based on the basic assumptions of the optimal tax theory ignores the two most significant twentieth-century advances in welfare economics. The first one is that, as Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky famously showed, people are concerned not only with the level of their income, but with changes in that level.[272] Anyone observing behavior of very high income individuals, be it corporate executives negotiating their compensation packages, star athletes negotiating their multi-million dollar deals, or any wealthy individual considering tax reduction strategies, has ample evidence that even at the highest levels of income, people do care about having even more of it, for better or worse. If so, their marginal utility of income is surely not zero. The same is true of the affluent, of course. So any argument for higher taxes at the top—whether the top 1% or 10%—has to accept utility losses by taxpayers facing a tax increase. There is no free lunch if we want to reduce high-end inequality.

The second important correction to the basic assumptions of welfare economics is that people are concerned not only with the absolute level of their income, but with this level relative to that of others: neighbors, coworkers, and other reference groups.[273] Office workers living in middle-class neighborhoods want the nicest houses in those neighborhoods. Multi-millionaires rubbing elbows in Florida marinas want the nicest boats in those marinas. In fact, Saez himself recently pointed out that “relative positions matter to people” and cited a “wide literature [that] has documented relative well-being effects.”[274] If so, the marginal utility of top earners is not only different from zero, but it may not be so different from that of the rest of us.

Finally, arguments about our actual tax system based on the optimal tax theory face a more general limitation: the theory has a highly attenuated connection to actual tax law.[275] So arguments relying on this theory to advocate reforming that law must be taken with a grain of salt. For all these reasons, Diamond and Saez hardly establish that the “main fault line” in America is between the one percent and everybody else.[276]

Another influential paper—by Piketty, Saez, and Stefanie Stantcheva—finds that the revenue-maximizing top marginal tax rate should be as high as 83%.[277] But, as in Diamond and Saez, the authors arrive at the 83% rate on the basis of an optimal tax model and while disregarding marginal utility of the one-percenters.[278] So all of the limitations just discussed apply to this argument as well. Moreover, this paper focuses on CEOs, assuming that most of their high earnings come from rent-seeking and that their tax avoidance is very limited. There are now strong reasons to question all of these conceptual moves.[279]

There are, of course, many other papers using the optimal tax theory to shed light on taxation of top incomes. But the two papers just discussed have set the standard, as their staggering citation counts clearly show.[280] Yet neither paper offers a strong theoretical case for imposing much higher taxes on the top one percent.[281] And the two papers surely do not present a theoretical case—strong or otherwise—in favor of not raising taxes on the affluent.