- I. Introduction

- II. Overview

- III. Reversals by Court

- IV. Reversals by Procedure

- A. Jury Trials

- B. Bench Trials

- C. Summary Judgments

- D. Default Judgments

- E. Temporary Injunctions

- F. Special Appearances

- G. Pleas to the Jurisdiction and Immunity Defenses

- H. Motions to Compel Arbitration

- I. Motions to Dismiss a Healthcare Liability Claim Based on an Expert Report

- J. Motions to Dismiss Under the Texas Citizens Participation Act

- V. Reversals by Type of Dispute

- VI. Conclusion

- Appendix A: Methodology

- Appendix B: Figures

I. Introduction

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.”[1]

—Sherlock Holmes

As Sherlock Holmes reminds us, it is a mistake to theorize before one has data. Detectives know this. Scientists know this. Lawyers know this too, but even in the absence of data, they frequently are called upon to theorize about reasons for reversal in the Texas courts of appeals. A trial lawyer must theorize about reasons for reversal when advising a client whether to accept a post-judgment settlement offer or pursue an expensive appeal. An appellate lawyer must theorize about reasons for reversal when narrowing the focus of an appeal and selecting the arguments to emphasize in the brief. And it is not only lawyers,[2] but also their clients and the public as a whole,[3] who theorize about reasons for reversal in the Texas courts of appeals.

How often do the courts of appeals reverse judgments entered on jury verdicts for plaintiffs in personal injury cases? Are these judgments reversed most often because of procedural errors occurring at trial, or because the evidence is legally or factually insufficient? Do different courts of appeals reverse different types of cases for different reasons? These questions cannot be answered solely from personal experience, war stories, observations by judges at continuing legal education programs, or lore passed down through generations of lawyers. Answering these questions requires data.

Eighteen years ago, in 2002, Lynne Liberato and Kent Rutter conducted a study to find that data.[4] In 2011, they repeated the study.[5] In 2019, the Authors conducted the study a third time to determine what has changed, and what has remained the same, about why courts reverse.

As before, the study began with a preliminary review of all opinions issued in civil appeals[6] by the fourteen Texas courts of appeals[7] during an entire court year, the twelve-month period beginning September 1, 2018, and ending August 31, 2019.[8] To present an accurate picture, certain types of opinions were then excluded from the analysis as described in Appendix A.[9] For example, appeals in juvenile cases, although categorized by the Texas courts as civil cases, were excluded because in reality they are quasi-criminal in nature.[10] Also excluded were appeals that were not decided on the merits, such as appeals that were dismissed for want of prosecution and appeals in which an affirmance or reversal was entered at the request of the parties pursuant to settlement.[11] The remaining decisions—1,690 in all—form the basis of the findings presented here.[12]

This Article first identifies the statewide reversal rate and the rate for each of the fourteen courts of appeals in civil cases.[13] It then examines reversal rates and reasons for reversal in various procedural contexts, including reversals following jury trials, bench trials, summary judgments, and default judgments, as well as reversals of orders granting or denying temporary injunctions, special appearances, pleas to the jurisdiction, motions to compel arbitration, motions to dismiss a healthcare liability claim based on an expert report, and motions to dismiss under the Texas Citizens Participation Act (TCPA).[14] After considering reversals from a procedural standpoint, the Article switches to a substantive perspective, examining reversal rates and reasons for reversal in tort and Deceptive Trade Practices Act (DTPA) cases, contract cases, family cases, probate cases, and property cases.[15]

When this study was first published in 2002, it “caus[ed] a stir in legal circles” by showing that certain types of appeals fared better in some courts than others.[16] The current study confirms that the courts of appeals are not interchangeable and that some types of appeals succeed more than others. Already, the current study has been cited[17]—as past studies were[18]—as support for various opinions about the fairness of the appellate process. As before, however, the aim of the study is not to imply that any court of appeals reverses any type of judgment on any particular ground too frequently, or not frequently enough.[19] No attempt was made to evaluate whether the opinions were persuasively reasoned or applied the law correctly. Nor was there any analysis of the briefs, the records on appeal, or any further action in or by the Supreme Court of Texas.

Thus, instead of presenting an argument about which types of judgments the courts of appeals ought to reverse, this Article presents the facts about which types of judgments they actually do reverse. While there is no substitute for the good judgment of a lawyer in assessing a potential appeal, this Article provides a tool to better inform the lawyer’s and client’s decision.

II. Overview

Some of the results of the study confirm conventional expectations about appeals. Other results are surprising. Some of the key findings are as follows:

A. The statewide reversal rate in civil cases was 30%, significantly below the 36% reversal rate during the 2010–2011 court year. Reversal rates for judgments on jury verdicts, judgments following bench trials, and summary judgments all declined.[20]

B. Compared to two earlier studies, fewer appeals were taken from judgments on jury verdicts, judgments following bench trials, and summary judgments. More appeals were taken from interlocutory orders, which take up an increasing share of the dockets of the courts of appeals.[21]

C. The reversal rate for judgments on jury verdicts varied significantly between Dallas and Houston. The Dallas court of appeals reversed 20% of judgments on jury verdicts, while the Houston First and Fourteenth courts of appeals reversed 38% and 39% respectively.[22]

D. The reversal rate for orders denying motions to compel arbitration was 70%, the highest of all rulings studied. This reflects a strong policy favoring arbitration agreements.[23]

E. Tort and DTPA defendants found it much more difficult to win on appeal. In the earlier studies, tort and DTPA defendants prevailed in about half the appeals they pursued. During the 2018–2019 court year, the reversal rate fell to 27%.[24]

F. Outcomes in tort and DTPA cases changed dramatically in Austin, Dallas, and Houston, where Democratic majorities joined previously all-Republican courts in January 2019. Comparing the last four months of 2018 to the first eight months of 2019 in these courts, the reversal rate in appeals by tort and DTPA defendants fell from 39% to 17%, while the reversal rate in appeals by tort and DTPA plaintiffs rose from 5% to 18%.[25]

III. Reversals by Court

As shown in Figure 1, the statewide reversal rate in civil cases was 30%. Seven of the fourteen courts of appeals, including the largest courts, were within 1% of the average. The Texarkana court of appeals reversed at the lowest rate (22%), while the Amarillo court reversed at the highest rate (36%).[26]

The 30% statewide reversal rate during the 2018–2019 court year is significantly lower than the 36% reversal rate in 2010–2011.[27] This decline occurred despite—not because of—changes in the composition of the dockets of the courts of appeals. During the 2018–2019 court year, only 54% of the decisions studied were appeals from final judgments following trials or summary judgments—a lower percentage than seen in the earlier studies. Other types of appeals, including appeals from interlocutory orders, are taking up an increasing share of the dockets of the courts of appeals. The shift in appellate dockets exerted an upward force on reversal rates, given that reversal rates in appeals following trials and summary judgments are consistently lower than reversal rates in other appeals. Yet the overall reversal rate declined.

One explanation may be that reversal rates were unusually high during the 2010–2011 court year due to turnover on the trial courts. In Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio, many trial benches changed hands from Republicans to Democrats following the 2006 and 2008 elections.[28] In contrast, the appellate courts in these cities remained overwhelmingly Republican.[29] This combination of Democratic trial judges and Republican appellate judges may have led to higher reversal rates in the years that followed. In Dallas, for example, the reversal rate for judgments on jury verdicts increased from 11% to 34% between the 2001–2002 and 2010–2011 court years, and the reversal rate for judgments following bench trials increased from 20% to 28%.[30] Chief Justice Carolyn Wright of the Dallas court of appeals agreed that these increased reversal rates in Dallas may have resulted from the election of Democratic trial judges.[31]

In the November 2018 elections, ten new Democratic justices were elected to Houston’s First and Fourteenth courts of appeals, eight new Democratic justices were elected to the Dallas court of appeals, four new Democratic justices were elected to the Austin court of appeals, and two new Democratic justices were elected to the San Antonio court of appeals.[32] The effect was to bring these courts into greater partisan alignment with the trial courts in their regions, which may have reduced reversal rates. Again citing Dallas as an example, reversal rates for judgments on jury verdicts fell from 34% to 20% between the 2010–2011 and 2018–2019 court years, and reversal rates for judgments following bench trials fell from 30% to 20%.[33]

This study’s finding of declining reversal rates is confirmed by figures compiled by the Office of Court Administration. According to those figures, reversal rates rose to peak levels between 2011 and 2013, then declined to the lowest levels seen in years between 2014 and 2019. Although the Office of Court Administration figures are useful in identifying trends, they cannot be compared directly with the reversal rates in this study. As in most years, the statewide reversal rate in this study is somewhat higher than the reversal rate that can be derived from statistics compiled by the Office of Court Administration.[34] The primary reason for the difference is that reversals are relatively uncommon in certain types of cases that were excluded from this study, but are included in the Office of Court Administration figures, such as appeals brought by inmates, juvenile delinquency cases, and parental termination cases.[35]

In general, it is no surprise that affirmances outnumber reversals. Indeed, low reversal rates suggest that the courts of appeals are mindful of the constraints on their power to reverse. For example, a court of appeals may not reverse, no matter how egregious the error, unless the complaining party made a request, objection, or motion in the court below that was proper, timely, and specific, and either obtained a ruling or objected to the trial court’s failure to rule.[36] The steps taken to preserve error must appear in the appellate record[37] because a court of appeals cannot find error in matters outside the record.[38] Nor may a court of appeals reverse without taking into account the deference owed to the trial court’s ruling under the applicable standard of review, because “standards of review define the parameters of a reviewing court’s authority in determining whether a trial court erred.”[39] Finally, under the doctrine of harmless error, a court of appeals may not reverse unless the error below “probably caused the rendition of an improper judgment” or “probably prevented the appellant from properly presenting the case to the court of appeals.”[40]

On the other hand, higher reversal rates can result when appellate judges invest the time and effort required to complete the hard task of reversing cases. Appellate dockets are crowded,[41] and appellate judges are busy.[42] If the appellant fails to show preservation and harm, there is no need for the court of appeals to reach the merits; it may quickly affirm and move on.[43] Even if the court of appeals does reach the merits, affirming is still often easier than reversing. For example, when a court of appeals overrules a complaint regarding the factual insufficiency of the evidence, its opinion need not contain anything beyond a short description of the evidence supporting the verdict, followed by a statement that the evidence is factually sufficient.[44] In contrast, when a court reverses on factual sufficiency grounds, it must describe all of the evidence and “state in what regard the contrary evidence greatly outweighs the evidence in support of the verdict.”[45] Similarly, when a court overrules a complaint that the trial court abused its discretion, its opinion is often succinct.[46] When reversing, a court must explain how the trial court’s ruling exceeded the bounds of its discretion.[47]

The reversal rates set forth above provide some basis for comparing the fourteen courts of appeals, but they are only a starting point. Certain types of cases are reversed frequently, even in the courts with the lowest reversal rates; other types of cases are reversed rarely, even in the courts with the highest reversal rates. The remainder of this Article identifies the reversal rates for specific types of cases and the most common reasons for reversal.

IV. Reversals by Procedure

Each of the cases studied was categorized according to the procedure by which it was decided in the trial court—for example, by jury trial, bench trial, or summary judgment. When different aspects of the case were decided by different procedures, the case was categorized according to the procedure that was the focus of the appeal. Thus, if the focus of the appeal was a partial summary judgment granted on some issues, rather than the subsequent jury trial on the remaining issues, the case was categorized as a summary judgment.[48]

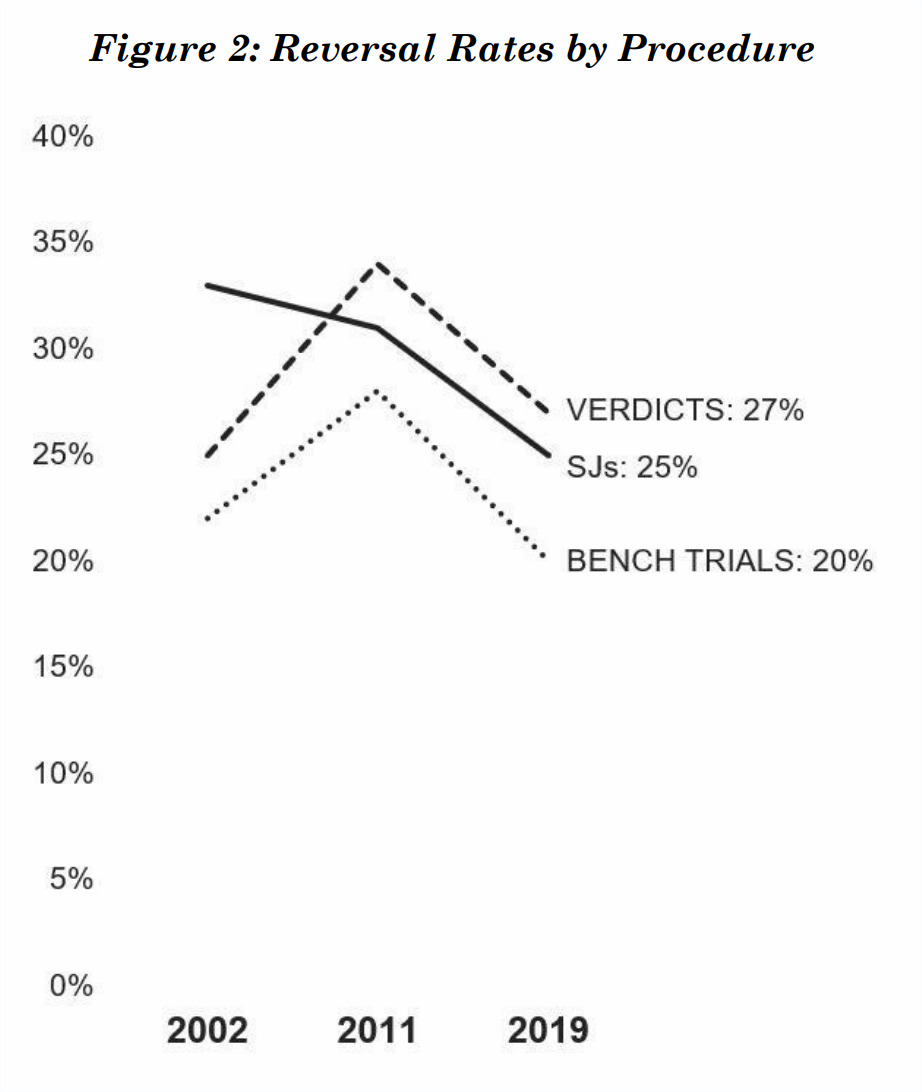

As shown in Figure 2, in appeals from judgments entered on jury verdicts, the reversal rate was 27%. In appeals following bench trials, the reversal rate was 20%. In appeals from summary judgments, the reversal rate was 25%.[49] In other types of appeals, as discussed below, the reversal rates generally were higher.

These findings refute the widely held supposition that courts of appeals reverse summary judgments at a higher rate than judgments entered on jury verdicts. As shown in Figure 2, the conventional wisdom was correct at one time: during the 2001–2002 court year, the reversal rate for summary judgments was 33%, while the reversal rate for judgments entered on jury verdicts was 25%.[50] But during the 2010–2011 court year, the courts of appeals reversed judgments entered on jury verdicts at a higher rate (34%) than summary judgments (31%)—even though the presumptions and standards of review applicable on appeal generally run in favor of judgments entered on jury verdicts and against summary judgments.[51] This held true during the 2018–2019 court year, with a reversal rate for jury verdicts of 27% and a reversal rate for summary judgments of 25%.

As shown in Figure 3, the number of appeals following jury trials has decreased by 45% between the 2001–2002 court year and the 2018–2019 court year, and the number of appeals following bench trials likewise decreased by 45% during this period.[52] This data reflects the issue of the “vanishing civil jury trial” that many judges and attorneys have discussed.[53] In contrast, the number of summary judgment appeals increased by 186% over the same period.

A. Jury Trials

As shown in Figure 4, in appeals from judgments entered on jury verdicts, the statewide reversal rate was 27%.[54] In contrast, when the trial court directed a verdict or signed a judgment notwithstanding the verdict, the reversal rate was 29%.

Figure 4 provides the reversal rates for the three courts that reviewed the most judgments entered on jury verdicts. Of these courts, Houston’s First and Fourteenth courts of appeals reversed more often than the statewide average (38% and 39% respectively), while the Dallas court of appeals reversed less often than the statewide average (20%).[55]

An appellant’s chances of success depended in large part on the grounds for the appeal. As shown in Figure 5, when the trial court signed a judgment on a jury verdict, the most common reason for reversal was that the evidence was legally insufficient to support the verdict or one of the parties was otherwise entitled to judgment as a matter of law.[56] This category, which accounted for 64% of the reversals, encompasses issues that are reviewed on appeal under a de novo standard. For example, this category includes judgments reversed because there was no evidence, or legally insufficient evidence, to support causation,[57] damages,[58] or another element of the cause of action.[59] This category also includes judgments reversed because the jury found contrary to a fact that had been established conclusively, as a matter of law.[60] Also included in this category were other errors of law, such as when the judgment awarded relief on a negligent misrepresentation claim that sounded in contract[61] or a covenant not to compete that was unenforceable.[62]

The second most common reason for reversal was jury charge error, which accounted for 14% of the reversals.[63] Only 10% of the reversals resulted from challenges to the factual sufficiency of the evidence and contentions that the verdict was against the great weight and preponderance of the evidence.[64] Factual sufficiency and great weight points require an evaluation of the evidence.[65] Although the courts of appeals are authorized to make such evaluations,[66] they are reluctant to do so because of the fine line they must tread to avoid substituting their views for those of juries.[67] As one court observed, “factual sufficiency is a demanding standard for litigants to meet and a difficult one for courts of appeals to apply.”[68] Finally, 12% of reversals were for other reasons,[69] including errors in forming the judgment.[70] Complaints about the discretionary admission or exclusion of evidence, though often raised, did not result in a single reversal on appeal.

B. Bench Trials

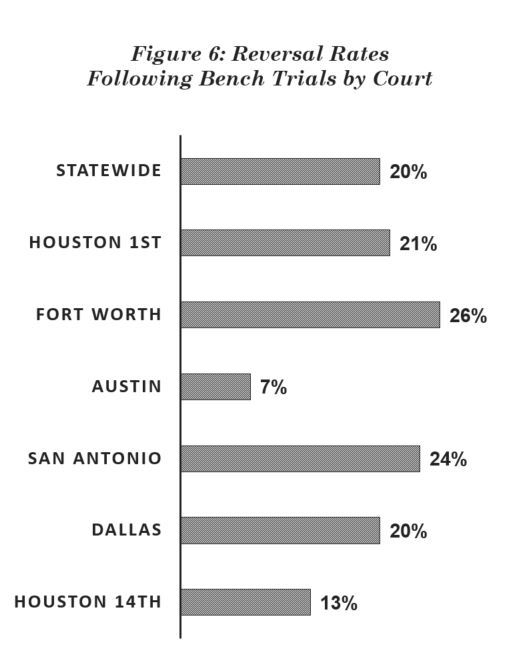

As shown in Figure 6, in appeals following bench trials, the statewide reversal rate was 20%. Figure 6 provides the reversal rates for the courts of appeals that reviewed the most judgments following bench trials.[71] Among these courts, the reversal rate ranged from 7% in the Austin court of appeals to 26% in the Fort Worth court of appeals.[72]

For purposes of this study, a case was categorized as a bench trial if significant fact issues were tried to the bench, regardless of whether the procedure was referred to as a “bench trial.” If the issues tried to the bench were incidental to issues decided on summary judgment or tried to the jury, such as when attorney’s fees were tried to the bench following a summary judgment[73] or jury trial[74] on liability, the case was not categorized as a bench trial.

Bench trials are common in family law cases, which accounted for 45% of the bench trials included in the study. As shown in Figure 7, the reversal rate following bench trials varied based on the type of dispute. In appeals following bench trials in family law cases, the reversal rate was 20%. In appeals following bench trials in contract cases, the reversal rate was 34%. For all other cases, the reversal rate was 16%.[75]

As shown in Figure 8, the most common reason for reversal following bench trials was that the evidence was legally insufficient to support the judgment or one of the parties was otherwise entitled to judgment as a matter of law. These grounds accounted for 89% of the reversals.[76] Examples include judgments that were reversed because of the statute of limitations,[77] no evidence of a fiduciary relationship,[78] improper characterization of property in a divorce proceeding,[79] the plain language of an ordinance,[80] and lack of proof of a meeting of the minds on an essential contract term.[81] During the 2018–2019 court year, not a single judgment following a bench trial was reversed based on a determination that the trial court’s findings were supported by factually insufficient evidence, or were against the great weight and preponderance of the evidence.

The remaining reversals following bench trials were based on errors in procedure, which accounted for 11% of the reversals.[82] Examples included commencing a bench trial in violation of a stay order without notice,[83] conducting a bench trial when a jury trial was required,[84] and signing the judgment even though a different judge had presided over the bench trial.[85] Like judgments on verdicts, judgments on bench trials are rarely reversed based on the erroneous admission or exclusion of evidence. In fact, during the 2018–2019 court year, there were no reversals for this reason.

C. Summary Judgments

Summary judgments[86] are frequently appealed. As shown in Figure 3, the number of summary judgment appeals rose dramatically between the 2001–2002 court year and the 2010–2011 court year. Although the number of summary judgment appeals declined for the 2018–2019 court year, summary judgments accounted for more appeals than any other type of judgment.[87]

As shown in Figure 9, in appeals from summary judgments, the statewide reversal rate was 25%. Figure 9 provides the reversal rates for the courts that reviewed the most summary judgments. Among these seven courts, the reversal rates of five courts were within just 2% of the statewide average, while the Corpus Christi court of appeals reversed at the lowest rate (20%) and the Fort Worth court of appeals reversed at the highest rate (35%).[88]

The reversal rates for summary judgments may say more about the trial courts within a particular court of appeals region than the courts of appeals themselves. In areas where trial courts grant summary judgments only rarely, to dispose of the weakest of cases, relatively few summary judgments will be reversed. In contrast, in areas where trial courts more willingly grant summary judgments in closer cases, there will inevitably be more instances in which the courts of appeals disagree, and reversal rates will be higher.

Most summary judgments are granted in favor of defendants, who may obtain a summary judgment by proving as a matter of law all elements of an affirmative defense,[89] by disproving as a matter of law an essential element of the plaintiff’s claim,[90] or by alleging that the plaintiff lacks evidence to support an essential element of its claim.[91] While it is possible for a plaintiff to obtain a summary judgment on any element of its claim other than damages,[92] even without negating the defendant’s affirmative defenses,[93] summary judgments for plaintiffs are relatively rare. Forty-one percent of the summary judgments appealed were granted for personal injury tort defendants,[94] defendants in other tort and DTPA cases,[95] employers in employment cases,[96] or insurers in insurance coverage cases;[97] while only 3% of summary judgments appealed were granted for the plaintiff in these cases.[98] Twenty-four percent of the summary judgments appealed were granted in contract cases, where the traditional plaintiff/defendant roles are blurred.[99]

As shown in Figure 10, summary judgments for tort defendants, employers, and insurers in the cases discussed above were reversed at a significantly lower rate than summary judgments in all cases combined (15% compared to 25%), while summary judgments in contract cases were reversed at a significantly higher rate than summary judgments in all cases combined (41% compared to 25%).[100]

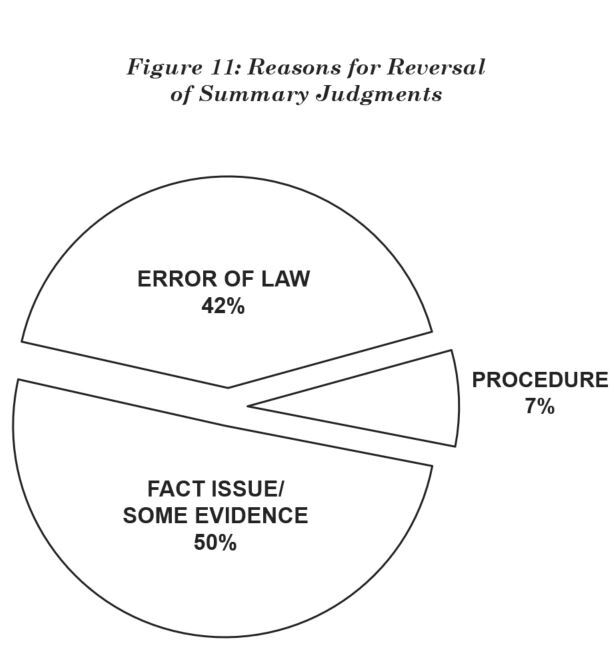

As shown in Figure 11, 50% of summary judgment reversals were attributed to the existence of fact issues[101] (including, in appeals from no-evidence summary judgments, the existence of some evidence raising fact issues).[102] Of the reversals, 42% were attributed to errors of law—for example, an incorrect determination regarding when the limitations period began to accrue[103] or whether the claims fell within an insurance coverage exclusion and thus the insurer did not owe a duty to defend.[104] Only 7% of the reversals were based on procedural errors,[105] such as granting summary judgment before ruling on a motion to transfer venue[106] or without allowing the plaintiff to first amend her claims.[107] In comparison, during the 2010–2011 court year, 18% of the reversals resulted from procedural errors.[108] In the eyes of the courts of appeals, Texas lawyers and judges are becoming more proficient or more careful when requesting and granting summary judgments.

Only 8% of the summary judgment appeals were from pure no-evidence summary judgments. Of those, 43% were in personal injury cases, accounting for 19% of the total summary judgment appeals in personal injury cases.[109] When the summary judgment motion was based solely on no-evidence grounds, the reversal rate was 22%, which is slightly lower than the reversal rate of 25% in appeals from traditional or hybrid summary judgments.[110]

D. Default Judgments

As shown in Figure 12, appeals from no-answer default judgments had a relatively high reversal rate—54%.[111] No-answer default judgments are entered when a defendant fails to appear in the case.[112] When no-answer default judgments were reversed, the most common reason was a defect in service, meaning that the trial court never obtained personal jurisdiction over the defendant and the defendant never had notice of the suit.[113]

No-answer default judgments are reversed at higher rates than post-answer default judgments.[114] Post-answer default judgments are entered when a defendant, having appeared in the case, fails to appear for trial or a hearing.[115] Post-answer default judgments generally cannot be reversed based on defective service because a defendant waives any objections to personal jurisdiction by generally appearing in the lawsuit.[116]

The reversal rate depended not only on the type of default judgment, but also the method used to challenge the default judgment.[117] When the trial court granted a default judgment and then denied a motion for new trial, the reversal rate was 30%—significantly lower than the reversal rate of 66% for the 2001–2002 court year and the reversal rate of 71% for the 2010–2011 court year.[118] When a motion for new trial was not filed and the default judgment went unchallenged until the defendant perfected a restricted appeal, the reversal rate was 59%—somewhat lower than the reversal rate of 74% for the 2001–2002 court year and the reversal rate of 62% for the 2010–2011 court year.[119]

At first glance, it might appear surprising that the reversal rate is lower when the defendant discovers the default judgment in time to file a motion for new trial, and higher when the defendant discovers the default judgment too late to file a motion for new trial and therefore files a restricted appeal.[120] The reason for this apparent incongruity may lie in the applicable standards of review and principles of self-selection.

Typically, an appeal from the denial of a motion for new trial will raise an argument that a new trial was warranted under Craddock v. Sunshine Bus Lines, Inc.[121] Craddock holds that “a default judgment should be set aside [and a new trial granted] when the defendant establishes that (1) the failure to answer was not intentional or the result of conscious indifference, but the result of an accident or mistake, (2) the motion for new trial set up a meritorious defense, and (3) granting the motion will occasion no undue delay or otherwise injure the plaintiff.”[122] A trial court’s application of the Craddock test is reviewed for an abuse of discretion.[123] Because “appellate courts will differ on the delicate question of whether trial courts have abused their discretion,”[124] in almost every case an appeal offers at least some hope of reversal, and defendants often are inclined to try.

In contrast, the appellant in a restricted appeal cannot raise a Craddock argument and must instead show an error that is apparent on the face of the record,[125] such as improper service.[126] Most of these issues are subject to de novo review. Moreover, because the law governing default judgments is relatively well settled, defendants can often predict whether a default judgment will be set aside and appeal only if reversal is likely. Thus, the reversal rate of 59% may indicate that defendants are selective in pursuing restricted appeals, not that most default judgments are susceptible to reversal in restricted appeals.

E. Temporary Injunctions

As shown in Figure 12, in appeals from orders granting temporary injunctions,[127] the reversal rate was 33%.[128] This is lower than in the past, when reversal rates were consistently above 50%,[129] but still relatively high, given that temporary injunctions are reviewed under a lenient abuse-of-discretion standard.[130]

The reason for the relatively high reversal rate may be that lawyers generally appeal from temporary injunctions only when the grounds for reversal are compelling, as shown by the relatively low number of appeals from temporary injunctions.[131] In most cases, there is little to be gained from an appeal. Appeals from temporary injunctions, unlike other interlocutory appeals, do not stay the commencement of a trial on the merits.[132] Thus, an appeal often serves only to intensify the litigation, in effect expanding the battle to two fronts. Indeed, even though appeals from temporary injunction orders are accelerated,[133] in some venues the trial on the merits may occur before the appeal can be decided.[134] Even if the trial will be delayed until the parties have conducted significant discovery, an appeal may be inadvisable because the enjoined party will find it difficult, in the early stages of a complex case, to persuade the court of appeals that the trial court abused its discretion by preserving the status quo until the facts could be discovered and the issues tried. Finally, even if the appeal is decided before the case is tried, the appeal will not obviate the need for a trial unless the court of appeals bases its decision on pivotal legal grounds that become the law of the case.[135] Confronted with all of these reasons not to appeal, temporarily enjoined parties may limit appeals to exceptional cases in which the temporary injunction is highly disruptive and plainly unjustified.

F. Special Appearances

An interlocutory appeal may be taken from an order denying a special appearance and assuming jurisdiction over the defendant’s person and property.[136] As shown in Figure 12, in these appeals, the reversal rate was 35%.[137] This rate is relatively high, most likely because personal jurisdiction is an issue of law.[138] Thus, in appeals from denials of special appearances, the ultimate issue is reviewed under a de novo standard.[139] This is true even though the trial court sometimes must resolve issues of fact before reaching the ultimate issue of law, and fact findings are reviewed for legal and factual sufficiency.[140]

G. Pleas to the Jurisdiction and Immunity Defenses

As shown in Figure 13, when a government entity or government official successfully asserted an immunity defense in the trial court, the reversal rate was 25%.[141] Most of these appeals were from orders granting pleas to the jurisdiction (91%).[142] The remaining appeals were from summary judgments (2%)[143] or motions to dismiss under Texas Rule of Civil Procedure 91a (7%).[144]

When an immunity defense was rejected by the trial court, the reversal rate was considerably higher—63%.[145] Most of these appeals were from orders denying pleas to the jurisdiction (98%).[146] The remaining appeals were from orders denying motions for summary judgment (2%).[147] In either context, the rejection of an immunity defense is subject to an interlocutory appeal.[148]

H. Motions to Compel Arbitration

An interlocutory appeal may be taken from an order denying a motion to compel arbitration.[149] As shown in Figure 12, in these appeals, the reversal rate was 70%—the highest among all rulings studied.[150] This reflects that a strong policy exists favoring arbitration agreements.[151] The high reversal rate further reflects that, although refusal to compel arbitration is reviewed for an abuse of discretion, the abuse-of-discretion standard entails reviewing legal determinations de novo.[152] A de novo standard applies to the key issues in most appeals from orders refusing to compel arbitration, including whether claims fall within the scope of the arbitration agreement and whether the arbitration agreement is enforceable.[153]

I. Motions to Dismiss a Healthcare Liability Claim Based on an Expert Report

An interlocutory appeal may be taken from an order denying a motion to dismiss a healthcare liability claim for failure to timely serve a sufficient expert report under the Texas Medical Liability Act.[154] As shown in Figure 12, for these appeals, the reversal rate was 30%.[155]

J. Motions to Dismiss Under the Texas Citizens Participation Act

An appeal may be taken from either a final judgment granting a motion to dismiss under the Texas Citizens Participation Act (TCPA) or an interlocutory order denying a motion to dismiss under the TCPA.[156] There were insufficient numbers of appeals from orders granting TCPA motions to dismiss to provide a reliable sample. In appeals from orders denying TCPA motions to dismiss, the reversal rate was 17%, one of the lowest among of all rulings studied.[157] This low reversal rate for denials of dismissal, combined with the low number of appeals from grants of dismissal, sheds light on how trial and appellate judges resolved an apparent conflict between the narrow intended purpose of the TCPA and the broad terms of the statute as it existed during the 2018–2019 court year.

The TCPA was conceived as an “anti-SLAPP” statute, meant to protect citizens from “retaliatory lawsuits that seek to intimidate or silence them on matters of public concern.”[158] As the Texas Supreme Court explained, however, the terms of the statute support a broader application, including either public or private “communications” having only a “tangential relationship” to a matter of public concern.[159] Therefore, the Court concluded, the TCPA does not “only apply to constitutionally guaranteed activities.”[160] As one opinion put it, “[t]he hypothetical situations and communications to which the TCPA could apply are endless,” and “any skilled litigator could figure out a way to file a motion to dismiss under the TCPA in nearly every case.”[161] Given the broad language of the statute, some lawyers have concluded that “it could be malpractice to not file a TCPA motion in practically any civil case.”[162] Defense counsel took that warning to heart, filing TCPA motions in civil cases of virtually all kinds, including lease disputes, commercial contracts, fraud claims, DTPA claims, legal malpractice claims, employment discrimination claims, and others.

It does not appear that trial judges shared this enthusiasm for a broad application of the TCPA. If trial courts had granted questionable TCPA motions in significant numbers, that presumably would have led to large numbers of appeals from TCPA dismissals—yet, as noted above, there were very few. In contrast, there were significant numbers of appeals from orders denying questionable TCPA motions—and as noted above, these appeals generally resulted in affirmance. Taken together, these statistics indicate that both the courts of appeals and trial courts have rejected expansive applications of the TCPA.

Effective after conclusion of the 2018–2019 court year that is the basis of this study, the legislature amended and narrowed the TCPA,[163] bringing the language of the statute into better alignment with its intended purpose—and, it appears, with the manner in which the courts of appeals and trial courts were applying the TCPA already.

V. Reversals by Type of Dispute

Dispositions on appeal were affected not only by the procedural posture of the case, but also by the nature of the dispute. Accordingly, the appeals analyzed in this study were categorized by substance as well as procedure. Appeals in which the merits were not actually litigated below—such as appeals from default judgments, temporary injunctions, and orders on special appearances, pleas to the jurisdiction, and motions to compel arbitration—were excluded from this portion of the analysis.

A. Tort and DTPA Cases

1. Filing Trends

As shown in Figure 14, since the 2001–2002 court year, the number of appeals in tort and DTPA[164] cases has fallen by 36%, with appeals by plaintiffs declining by 44% and appeals by defendants declining by 10%. The 36% decline in tort and DTPA appeals is similar to the 32% decline in the number of cases classified by the Office of Court Administration as “injury or damage” cases that were decided by jury trial, bench trial, or summary judgment during the same period.[165]

Focusing specifically on personal injury cases (including wrongful death and medical malpractice cases), the number of appeals has declined by 54% since the 2001–2002 court year, with appeals by plaintiffs and defendants declining at approximately the same rate.

The steepest decline in tort and DTPA appeals occurred between the 2001–2002 and 2010–2011 court years, when tort reform measures enacted by the legislature, as well as Texas Supreme Court decisions favoring tort defendants, discouraged some tort plaintiffs from filing suit. According to the Office of Court Administration, between 2002 and 2011, the number of “injury or damage” cases filed in the trial courts fell by 11%.[166] Many Texas attorneys, having built their careers representing personal injury plaintiffs, focused their attention elsewhere. The founder of one prominent plaintiffs’ firm explained: “If today we were relying on personal-injury cases in Texas, we would be bankrupt.”[167]

When lawyers did file tort cases, they were often hesitant to turn down a settlement offer and pursue the case to judgment.[168] According to the Office of Court Administration, between 2002 and 2011, the number of “injury or damage” cases decided by summary judgment, jury trial, or bench trial fell by 20%.[169] And when tort cases did reach final judgment, plaintiffs were often hesitant to appeal an adverse result.[170] The number of appeals from final judgments taken by tort plaintiffs plunged by 39% between the 2001–2002 and 2010–2011 court years, while the number of appeals from final judgments taken by tort and DTPA defendants fell by 6%.

After 2011, case filings not only rebounded, but surged. According to the Office of Court Administration, between 2011 and 2019, the number of “injury or damage” cases filed in the trial courts rose every year, increasing over the eight-year period by 75%.[171] But even as more cases were filed, fewer were taken to final judgment. According to the Office of Court Administration, between 2011 and 2019, the number of “injury or damage” cases decided by summary judgment, jury trial, or bench trial fell by 13%.[172]

The number of tort and DTPA appeals declined during this period as well. Between the 2010–2011 and 2018–2019 court years, the number of tort and DTPA appeals decreased by 10% statewide, with particularly steep decreases in the Houston First (down 30%), San Antonio (down 36%), and Houston Fourteenth (down 31%) courts of appeals. The number of appeals taken by tort and DTPA plaintiffs declined by only 9%, while the number of appeals taken by tort and DTPA defendants declined by only 3%. There were steeper declines in personal injury cases, with the number of appeals taken by plaintiffs decreasing by 16% and the number of appeals taken by defendants decreasing by 39%.

2. Reversal Rates.

As in prior studies, plaintiffs in tort and DTPA cases did not fare as well as defendants on appeal. As shown in Figure 15, when the plaintiff prevailed in the trial court and the defendant appealed, the reversal rate was 27%. When the defendant prevailed in the trial court and the plaintiff appealed, the reversal rate was 17%.[173] As shown in Figure 16, focusing specifically on personal injury cases, when the plaintiff prevailed in the trial court and the defendant appealed, the reversal rate was 34%. When the defendant prevailed in the trial court and the plaintiff appealed, the reversal rate was 16%.[174]

Although tort and DTPA defendants continued to fare better than plaintiffs on appeal, they did not fare nearly as well as they have in the recent past. After reversing judgments favoring plaintiffs at rates of 51% and 49% during the 2001–2002 and 2010–2011 court years respectively,[175] the reversal rate plummeted to 27% during the 2018–2019 court year.[176] With respect to jury trials, after reversing judgments on plaintiffs’ verdicts at a rate of 49% and 50%[177] during the 2001–2002 and 2010–2011 court years, the reversal rate fell to 31% during the 2018–2019 court year.

Reversal rates in appeals by tort and DTPA plaintiffs declined as well, though not to the same degree. The reversal rates in appeals by tort and DTPA plaintiffs were 23%, 25%,[178] and 17% during the 2001–2002, 2010–2011, and 2018–2019 court years, respectively.[179] This shift stemmed largely from summary judgment appeals, which accounted for most of the appeals by tort and DTPA plaintiffs. The reversal rate for summary judgments granted for defendants in tort and DTPA cases declined from 28% to 14% between the 2010–2011 and 2018–2019 court years. This more than offset a slight increase in the reversal rate for judgments entered on defense verdicts in tort and DTPA cases, which rose from 11%[180] to 15% between the 2010–2011 and 2018–2019 court years. Moreover, that slight increase does not indicate that the courts of appeals have become more inclined to reverse judgments on defense verdicts in tort and DTPA cases. Rather, it appears to reflect primarily that plaintiffs are growing more selective in appealing defense verdicts in tort and DTPA cases. The number of appeals from defense verdicts in tort and DTPA cases has declined 73% since the 2001–2002 court year.

It is unlikely that tort and DTPA plaintiffs will achieve much greater success in the future in appeals from defense verdicts. They lack the inherent advantage held by defendants, who frequently obtain reversals in appeals from plaintiffs’ verdicts on legal insufficiency or “matter of law” grounds,[181] taking advantage of the de novo standard of review on appeal. A plaintiff, in contrast, typically cannot obtain reversal of a defense verdict on legal insufficiency or “matter of law” grounds, because the plaintiff bears the burden of proof.[182] For the most part, judgments entered on defense verdicts were overturned only where an award of no damages or minimal damages was against the great weight and preponderance of the evidence.[183]

3. The 2018 Elections.

The November 2018 elections brought a significant partisan shift to four courts of appeals—the Houston First and Fourteenth, Austin, and Dallas courts.[184] All of the justices on those four courts had been Republicans until January 2019, when new Democratic majorities took the bench.[185]

To obtain an early look at whether the changed makeup of the courts was affecting outcomes in tort and DTPA cases, the study compared decisions issued during the last four months of 2018 and the first eight months of 2019. These statistics, which are based on approximately 200 appeals, should be approached with caution as they are based on relatively short time frames. It remains to be seen whether the first eight months of 2019 are predictive of how these four courts will decide tort and DTPA appeals in the future.

As shown in Figure 17, outcomes in tort and DTPA appeals changed significantly after the new Democratic justices joined these four courts of appeals. In appeals by tort and DTPA defendants, the reversal rate fell from 39% to 17%. In appeals by tort and DTPA plaintiffs, the reversal rate climbed from 5% to 18%. While a shift in favor of tort and DTPA plaintiffs was not unexpected,[186] the extent of the shift is significant.

This shift did not transform these courts into outliers. Rather, it generally brought them into alignment with trends occurring statewide. In appeals by tort and DTPA defendants in these four courts, there was a decrease of 31 percentage points in the reversal rates between the 2010–2011 court year (when the reversal rate was 48%) and the first eight months of 2019 (when the reversal rate was 17%). In the other ten courts of appeals, the trend was downward as well—there was a decrease of 19 percentage points between the 2010–2011 court year (when the reversal rate was 50%) and the 2018–2019 court year (when the reversal rate was 31%).

In appeals by plaintiffs in tort and DTPA cases, in these four courts there was a decrease of 8 percentage points (from 26% during the 2010–2011 court year to 18% during the first eight months of 2019) in the reversal rates for these appeals. In the other ten courts of appeals, there was a decrease of 4 percentage points (from 24% during the 2010–2011 court year to 20% during the 2018–2019 court year) in the reversal rates for these appeals.

B. Contract Cases

As shown in Figure 18, the statewide reversal rate in contract cases was 35%.[187] Reversal rates were higher in contract appeals than other types of appeals, regardless of the procedure by which the case was decided in the trial court. In appeals from judgments on jury verdicts in contract cases, the reversal rate was 28% (compared to 27% for judgments on jury verdicts overall). In appeals from judgments following bench trials in contract cases, the reversal rate was 34% (compared to 20% for judgments following bench trials overall). In appeals from summary judgments in contract cases, the reversal rate was 41% (compared to 25% for summary judgments overall).

C. Family Cases

As shown in Figure 19, the reversal rate in family cases[188] was 21%. In divorce cases, including actions to enforce or modify existing decrees, the reversal rate was 24%. In suits to modify the parent-child relationship, the reversal rate was 19%. In child support cases, including actions to collect child support or modify a child support obligation, the reversal rate was 23%.[189]

D. Probate Cases

As shown in Figure 20, in probate appeals, the reversal rate was 18%.[190] This is one of the lowest reversal rates of any type of appeal, and it is significantly lower than the 2011–2012 court reversal rate of 31% for probate appeals.[191]

E. Property Cases

As shown in Figure 20, in property cases, the reversal rate was 30%.[192] Property cases involved disputes over title ownership, easements, land partitions, deed restrictions, and condemnations, among other property-law matters.[193] Over half of the appeals in property cases were from summary judgments (52%), while 34% were from bench trials and only 7% were from jury trials.

VI. Conclusion

This study aims to help lawyers understand the types of cases that are most often reversed and the most common reasons for those reversals by providing and analyzing data about the appellate process. For practitioners formulating a post-judgment strategy, this study is meant to provide a starting point toward a reasoned, accurate evaluation of the potential appeal and a tool to use in selecting the points deserving the greatest emphasis on appeal.

Appendix A: Methodology

The goal in categorizing cases for this study, and in excluding certain types of civil cases from the study, was to provide practitioners with an accurate tool to use when evaluating potential appeals.[194] Providing an accurate assessment of why courts reverse involves as much art as science. It is not as simple as counting the affirmances and reversals in all civil appeals. For example, juvenile cases are categorized by the Texas courts as civil cases, but they were excluded from this study because in reality they are quasi-criminal in nature.[195] Also excluded, for similar reasons, were appeals brought by inmates, appeals in bond forfeiture cases, appeals in proceedings to expunge criminal records, and appeals of driver’s license revocations. Appeals challenging terminations of parental rights were likewise excluded. Indigent parents are entitled to state-appointed counsel in parental termination proceedings,[196] including an appeal.[197] As a result, these appeals form a substantial portion of the docket in some of the courts of appeals, outnumbering many other types of appeals following jury trials and bench trials. Because most of these appeals result in affirmance, inclusion of these cases would have significantly skewed the reversal rates for jury trials and bench trials in some courts. Finally, the study disregarded appeals disposed of without reference to the merits, including appeals dismissed for want of prosecution or because the appellant failed to pay the filing fee, and appeals in which affirmance or reversal was entered at the request of the parties pursuant to settlement. The remaining decisions form the basis of the findings presented here. The total number of opinions included in the study was 1,690.

Each of these 1,690 appeals was categorized in several ways. First, each appeal was categorized according to the procedure by which the case was decided in the trial court. These categories included appeals from judgments entered on jury verdicts, directed verdicts, judgments notwithstanding the verdict, judgments following bench trials, no-evidence summary judgments, traditional or “hybrid” summary judgments, orders denying summary judgment motions asserting immunity, no-answer default judgments, and post-answer default judgments. They also included appeals from orders on temporary injunctions, special appearances, pleas to the jurisdiction based on immunity grounds, other pleas to the jurisdiction, motions to compel arbitration, motions to dismiss healthcare liability claims for failure to timely serve a sufficient expert report, and motions to dismiss under the TCPA.

Next, each appeal was categorized according to the substantive nature of the dispute. These categories included personal injury cases, other tort cases and DTPA cases, contract cases, insurance coverage cases, family cases (including divorces, child support cases, and suits to modify the parent-child relationship), probate cases, employment cases, and property cases. When a case presented more than one claim, the case was categorized according to the aspect that was the primary focus on appeal. For example, if the trial court disposed of the plaintiff’s fraud claims on summary judgment and conducted a bench trial on the contract claims, the case was categorized as a contract case if the contract recovery was the focus of the appeal.

Tort and DTPA cases, insurance coverage cases, and employment cases were further categorized according to whether the plaintiff or defendant prevailed below. For purposes of this study, when neither party secured a complete victory in the trial court, the party with the greatest stake in an affirmance of the issues at the center of the appeal was designated as the prevailing party below.

Finally, each appeal was categorized as either an affirmance or a reversal. For purposes of this Article, an appeal was classified as an affirmance despite the judgment being modified or reversed in part, if the modification or reversal affected only a small portion of the judgment. For example, an appeal in a suit for damages was classified as an affirmance if the court of appeals left most of the damages undisturbed and reversed only a relatively small component of damages,[198] reversed only an incidental award of attorney’s fees,[199] or reversed only interests or costs.[200] Conversely, an appeal was classified as a reversal if the court of appeals reversed a significant portion of the judgment. For example, an appeal was classified as a reversal if the court of appeals reversed or suggested a remittitur of a large component of damages,[201] or reversed the majority of the significant claims or parties.[202]

Appendix B: Figures

The Authors gratefully acknowledge and thank Nadia Baldez, Michelle Meuhlen, PLS, Justina Gomez, and Sylvia Bratton for their administrative assistance with the preparation of this Article.

A. Conan Doyle, Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: A Scandal in Bohemia, in The Complete Sherlock Holmes 177, 179 (Garden City Publ’g Co. 1938) (1892).

See generally Tim Patton, To Appeal or Not to Appeal, That Is the Question, in 20th Annual Advanced Civil Appellate Practice Course ch. 6 (2006) (offering professional guidance regarding the viability of different kinds of appeals).

See Editorial, Publish or Perish: Unpublished Appellate Court Opinions Corrode Texas Law, Hous. Chron., Dec. 9, 2001, at 2C (editorializing against the former practice of issuing unpublished opinions on the ground that “citizens are less able to know what their elected justices are up to when so many of the decisions they make are not made public”).

Lynne Liberato & Kent Rutter, Reasons for Reversal in the Texas Courts of Appeals, 44 S. Tex. L. Rev. 431 (2003) (study based on the 2001–2002 court year).

Lynne Liberato & Kent Rutter, Reasons for Reversal in the Texas Courts of Appeals, 48 Hous. L. Rev. 993 (2012) (study based on the 2010–2011 court year).

The analysis is limited to appeals and excludes original proceedings.

The intermediate courts of appeals in Texas are the First Court of Appeals (Houston), Second (Fort Worth), Third (Austin), Fourth (San Antonio), Fifth (Dallas), Sixth (Texarkana), Seventh (Amarillo), Eighth (El Paso), Ninth (Beaumont), Tenth (Waco), Eleventh (Eastland), Twelfth (Tyler), Thirteenth (Corpus Christi–Edinburg), and Fourteenth (Houston). Tex. Gov’t Code §§ 22.202–.215.

This period coincides with the courts’ reporting periods, which end on August 31 of each year. See generally Office of Court Admin., 2019 Annual Statistical Report, *Tex. Jud. Branch [*hereinafter OCA 2019 Annual Report], https://www.txcourts.gov/statistics/annual-statistical-reports/2019/ [https://perma.cc/9P79-F7NE] (scroll to “Courts of Appeals” and download “Activity Detail”) (last visited Feb. 16, 2020) (reporting activity for the fiscal year ending on August 31, 2019).

See infra Appendix A.

See Ed Kinkeade, Appellate Juvenile Justice in Texas—It’s a Crime! Or Should Be, 51 Baylor L. Rev. 17, 18 (1999) (citing E.T.J. v. State, 766 S.W.2d 871, 873 (Tex. App.—Dallas 1989, no writ) (Kinkeade, J., dissenting) (arguing that the juvenile proceeding at hand was not entirely civil in nature)); see also infra Appendix A.

See infra Appendix A.

See infra Appendix A.

See infra Part III and Figure 1. All figures referenced in this Article can be found in Appendix B.

See infra Part IV.

See infra Part V.

Janet Elliott, Defendants Fare Better on Appeal, Study Finds, Hous. Chron., Nov. 6, 2003, at 27A.

Mark Curriden, Study: Texas Appellate Courts Getting Fairer to Plaintiffs, Tex. Lawbook (Sept. 23, 2019), https://texaslawbook.net/study-texas-appellate-courts-getting-fairer-to-plaintiffs/; see also Michelle Casady, New Dems on Texas Bench Made Courts More Jury-Friendly, Law360 (Sept. 24, 2019, 9:21 PM), https://www.law360.com/articles/1202144/new-dems-on-texas-bench-made-courts-more-jury-friendly (quoting appellate lawyer Alex Wilson Albright as saying “it definitely seems more fair to have the same percentage of reversals for plaintiffs and defendants”).

Mark Curriden, Likely Precedent-Setting Case Headed to Appeal, Dall. Morning News (Aug. 10, 2013, 6:54 PM), https://www.dallasnews.com/business/2013/08/10/likely-precedent-setting-case-headed-to-appeal/ [https://perma.cc/9HTE-SJ9R] (characterizing the study as finding that, “Texas appellate judges have shown little hesitancy to toss verdicts” by “flyspeck[ing] jury instructions . . . and second-guess[ing] jury decisions”); Janet Elliott, Judges & Lawyers Try to Explain High Appellate Reversal Rates, Tex. Lawbook (May 9, 2012), https://texaslawbook.net/judges-lawyers-try-to-explain-high-appellate-reversalrates/ (quoting trial lawyer Paula Sweeney as saying that “judges are disregarding the hard work of jurors,” which is “frustrating because it stands the constitution on its ear”).

See Elliott, supra note 16 (quoting a Texans for Lawsuit Reform spokesman who observed that “[n]o such analysis can be credible without examining the merits of each and every case and drawing conclusions as to whether the courts ruled according to the law and precedent and the facts of the case”).

See infra Part III and Figures 1 and 2.

See infra Part III and Figure 3.

See infra Part III and Figure 4.

See infra Section IV.H and Figure 12.

See infra Section V.A.2 and Figure 15.

See infra Section V.A.3 and Figure 17.

See infra Figure 1.

Liberato & Rutter, supra note 5, at 999.

In 2006, fifteen incumbent Republicans were defeated by Democratic challengers in Dallas County, and three incumbent Republicans were defeated by Democratic challengers in Bexar County. See 2006 General Election: Dallas County Race Summary, Tex. Sec’y State, https://elections.sos.state.tx.us/elchist127_county57.htm [https://perma.cc/2NPP-Q7WA] (last visited Feb. 22, 2020); 2006 General Election: Bexar County Race Summary, Tex. Sec’y State, https://elections.sos.state.tx.us/elchist127_county15.htm [https://perma.cc/85QE-3Q97] (last visited Jan. 1, 2020). In 2008, twenty incumbent Republicans were defeated by Democratic challengers in Harris County. See 2008 General Election: Harris County Race Summary, Tex. Sec’y State, https://elections.sos.state.tx.us/elchist141_county101.htm [https://perma.cc/63JP-ZYT4] (last visited Jan. 1, 2020).

See 2008 General Election: Race Summary Report, Tex. Sec’y State, https://elections.sos.state.tx.us/elchist141_state.htm [https://perma.cc/6LTA-E8RX] (last visited Jan. 1, 2020).

Compare Liberato & Rutter, supra note 4, at 440, 467, with Liberato & Rutter, supra note 5, at 1002, 1007.

See Elliott, supra note 18 (“There were a significant number of new judges who came to the trial bench as of the 1st of January '09. It is not unusual to have a higher number of reversals within the first few years after an influx of newly elected judges to the bench . . . .” (quoting Chief Justice Wright)).

See 2018 General Election: Race Summary Report, Tex. Sec’y State, https://elections.sos.state.tx.us/elchist331_state.htm [https://perma.cc/VWH2-NQMU] (last visited Jan. 1, 2020).

Compare Liberato & Rutter, supra note 5, at 1028, 1031, with infra Figures 4 and 6.

The Office of Court Administration categorizes cases according to whether the judgment or order was affirmed, reversed, “modified and/or reformed,” or “affirmed in part and in part reversed.” If half of the judgments and orders that were “modified and/or reformed” or “affirmed in part and in part reversed” are counted as affirmances, and the other half are counted as reversals, the Office of Court Administration’s reversal rate for the 2018–2019 court year is 24%. OCA 2019 Annual Report, supra note 8.

See infra Appendix A (explaining the methodology of the study).

Tex. R. App. P. 33.1. An exception is made in rare cases of “fundamental” error. See Mack Trucks, Inc. v. Tamez, 206 S.W.3d 572, 577 (Tex. 2006) (“Except for fundamental error, appellate courts are not authorized to consider issues not properly raised by the parties.”); Pirtle v. Gregory, 629 S.W.2d 919, 920 (Tex. 1982) (per curiam) (“Fundamental error survives today in those rare instances in which the record shows the court lacked jurisdiction or that the public interest is directly and adversely affected as that interest is declared in the statutes or the Constitution of Texas.”).

Tex. R. App. P. 33.1.

See, e.g., Intercontinental Grp. P’ship v. KB Home Lone Star L.P., 295 S.W.3d 650, 657–58 (Tex. 2009) (declining to reach the question of recovery for attorney’s fees due to the record’s silence on the matter).

W. Wendell Hall et al., Hall’s Standards of Review in Texas, 42 St. Mary’s L.J. 3, 244 (2010).

Tex. R. App. P. 44.1.

See OCA 2019 Annual Report, supra note 8 (reporting that during the 2019 fiscal year, the fourteen courts of appeals decided 2,391 civil appeals on the merits, continuing an upward trend).

See Sarah B. Duncan, Pursuing Quality: Writing a Helpful Brief, 30 St. Mary’s L.J. 1093, 1098–1100 (1999) (comparing the high volume of an appellate judge’s workload with the low level of available resources). Justice Duncan noted as follows: “As an appellate judge, I work substantially more than the forty hours a week I averaged after I became of counsel. The reason? Volume and limited resources.” Id. at 1098.

See Christopher R. Drahozal, Judicial Incentives and the Appeals Process, 51 SMU L. Rev. 469, 480 (1998) (“Appellate judges can (and do) avoid complicated issues by deciding on simpler grounds.”); see also Richard A. Posner, What Do Judges and Justices Maximize? (The Same Thing Everybody Else Does), 3 Sup. Ct. Econ. Rev. 1, 10–11 (1993) (observing the economic incentives in the “judiciary’s nonprofit structure”).

See Ellis Cty. State Bank v. Keever, 888 S.W.2d 790, 794 (Tex. 1994) (refusing to require that courts of appeals detail all the supporting evidence when upholding a trial court’s judgment). There is one exception: a court of appeals must provide a full analysis of all the evidence when overruling a complaint regarding the factual sufficiency of the evidence supporting an award of punitive damages. Transp. Ins. v. Moriel, 879 S.W.2d 10, 31 (Tex. 1994).

Pool v. Ford Motor Co., 715 S.W.2d 629, 635 (Tex. 1986).

See, e.g., Christian Care Ctrs., Found. v. Gooch, No. 05-10-00933-CV, 2011 WL 1534511 (Tex. App.—Dallas Apr. 25, 2011, pet. denied) (mem. op.) (explaining in four paragraphs why the trial court did not abuse its discretion when it denied a motion to dismiss).

See Hall et al., supra note 39, at 17 (“To find an abuse of discretion, the reviewing court ‘must determine that the facts and circumstances presented “extinguish any discretion [or choice] in the matter.”’” (alteration in original) (quoting Kaiser Found. Health Plan of Tex. v. Bridewell, 946 S.W.2d 642, 646 (Tex. App.—Waco 1997, orig. proceeding) (per curiam))).

E.g., McGill v. GJG Prods., Inc., No. 01-17-00937-CV, 2019 WL 2749888, at *1 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] June 25, 2019, no pet.); Republic Capital Grp., LLC v. Roberts, No. 03-17-00481-CV, 2018 WL 5289573, at *1–2 (Tex. App.—Austin Oct. 25, 2018, no pet.).

See infra Figure 2.

See infra Figure 2; Liberato & Rutter, supra note 4, at 439.

See Liberato & Rutter, supra note 5, at 1002; see also David Hittner & Lynne Liberato, Summary Judgments in Texas: State and Federal Practice, 60 S. Tex. L. Rev. 1, 124–25 (2019) (“In an appeal from a trial on the merits, the standard of review and presumptions run in favor of the judgment.” (citing Tex. Dep’t of Pub. Safety v. Martin, 882 S.W.2d 476, 482–83 (Tex. App.—Beaumont 1994, no writ))).

See infra Figure 3.

See, e.g., William V. Dorsaneo, III, The Decline of Anglo-American Civil Jury Trial Practice, 71 SMU L. Rev. 353, 354, 366–68 (2018); Hon. Jennifer Walker Elrod, Is the Jury Still Out?: A Case for the Continued Viability of the American Jury, 44 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 303, 318–19 (2012); Hon. Nathan L. Hecht, The Vanishing Civil Jury Trial: Trends in Texas Courts and an Uncertain Future, 47 S. Tex. L. Rev. 163, 163–70 (2005).

See infra Figure 4. This Figure includes only judgments entered on verdicts, not directed verdicts or judgments notwithstanding the verdict.

See infra Figure 4. Only the courts that decided at least twenty appeals from judgments on jury verdicts are listed separately in Figure 4. However, the statewide average is based on appeals from all fourteen courts of appeals.

See infra Figure 5.

Farmers & Merchs. Bank v. Hodges, No. 11-17-00121-CV, 2019 WL 2710043, at *5 (Tex. App.—Eastland June 28, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.); Bright v. Simpson, No. 11-17-00104-CV, 2019 WL 1941885, at *4 (Tex. App.—Eastland Apr. 30, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

Cargotec Corp. v. Logan Indus., No. 14-17-00213-CV, 2018 WL 6695806, at *1 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] Dec. 20, 2018, pet. filed) (mem. op.); Mitropoulos v. Pineda, No. 01-17-00795-CV, 2018 WL 6205855, at *8 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] Nov. 29, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.).

Bell Helicopter Textron, Inc. v. Dickson, No. 05-17-00979-CV, 2019 WL 3986298, at *4–5 (Tex. App.—Dallas Aug. 23, 2019, no pet.) (holding there was no evidence of the objective and subjective elements of gross negligence); Inland W. Dall. Lincoln Park Ltd. P’ship v. Nguyen, No. 05-17-00151-CV, 2018 WL 6583024, at *6 (Tex. App.—Dallas Dec. 14, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.) (holding there was no evidence of the scienter element of fraudulent inducement).

Gulledge v. Wester, 562 S.W.3d 809, 815, 819–20 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2018, pet. denied) (holding the evidence conclusively established that the substantiality and objective reasonableness requirements of nuisance were not met).

First Bank v. Brumitt, 564 S.W.3d 491, 496–97 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2018, no pet.).

Cent. States Logistics, Inc. v. BOC Trucking, LLC, 573 S.W.3d 269, 276–77, 281 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2018, pet. denied).

See, e.g., State Farm Lloyds v. MacKeen, No. 07-17-00175-CV, 2019 WL 2168041, at *1, *3–5 (Tex. App.—Amarillo May 17, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.) (holding the trial court abused its discretion by submitting a jury instruction stating that the defendant failed to comply with an insurance policy because the instruction was an improper comment on the weight of the evidence and did not aid the jury in answering the jury questions); Neal v. Guidry, No. 03-17-00525-CV, 2019 WL 2126889, at *3–5 (Tex. App.—Austin May 15, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.) (holding the trial court erred by refusing to submit a jury question on fraud in the inducement as a defense to breach of contract); Solis v. S.V.Z., 566 S.W.3d 82, 87, 92–94 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2018, pet. filed) (holding the trial court abused its discretion by submitting a jury instruction that prohibited consideration of the plaintiff’s consent when awarding damages for sexual assault and sexual harassment of a minor).

See infra Figure 5. For cases reversing on these grounds, see, for example, Cartwright v. Armendariz, No. 08-16-00129-CV, 2019 WL 2022221, at *4–5 (Tex. App.—El Paso May 8, 2019, pet. denied); Villarreal v. Timms, No. 04-18-00444-CV, 2019 WL 2014517, at *2 (Tex. App.—San Antonio May 8, 2019, no pet.); and State v. Buchanan, 572 S.W.3d 746, 750 (Tex. App.—Austin 2019, no pet.).

Plas-Tex, Inc. v. U.S. Steel Corp., 772 S.W.2d 442, 445 (Tex. 1989).

See Tex. Const. art. V, § 6 (“[T]he decision of [the courts of appeals] shall be conclusive on all questions of fact brought before them on appeal or error.”); Tex. Gov’t Code § 22.225(a) (“A judgment of a court of appeals is conclusive on the facts of the case in all civil cases.”).

Jackson v. Williams Bros. Constr. Co., 364 S.W.3d 317, 324–25 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2011, pet. denied).

Porter v. Heritage Operating, L.P., 569 S.W.3d 686, 724 (Tex. App.—El Paso 2018, pet. filed).

See infra Figure 5.

See Equistar Chems., LP v. ClydeUnion DB, Ltd., 579 S.W.3d 505, 525 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2019, pet. denied) (reversing because no damages should have been awarded after applying offset amounts); Meredith v. Chezem, No. 03-18-00256-CV, 2018 WL 6425017, at *4 (Tex. App—Austin Dec. 7, 2018, no pet.); MCJAM, Inc. v. CD Auto Serv., Inc., No. 04-17-00849-CV, 2018 WL 6331064, at *3 (Tex. App—San Antonio Dec. 5, 2018, no pet.) (reversing judgment for the plaintiff because the jury was never asked a question regarding the claim for affirmative relief but rather was asked about defensive issues only).

Only the courts that decided at least twenty appeals from judgments following bench trials are listed separately in Figure 6. However, the statewide average is based on appeals from all fourteen courts of appeals.

See infra Figure 6.

E.g., Garza v. Pruneda Law Firm, PLLC, No. 13-18-00222-CV, 2019 WL 2384155, at *1–2 (Tex. App.—Corpus Christi–Edinburg June 6, 2019, pet. denied) (mem. op.).

E.g., Davenport v. Hall, No. 04-14-00581-CV, 2019 WL 1547617, at *1–2, *7 (Tex. App.—San Antonio Apr. 10, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

See infra Figure 7.

See infra Figure 8.

Jarvis v. Lovin, No. 12-17-00403-CV, 2018 WL 4907824, at *1, *4 (Tex. App.—Tyler Oct. 10, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.).

PlainsCapital Bank v. Reaves, No. 05-17-01184-CV, 2018 WL 6599020, at *3, *5 (Tex. App.—Dallas Dec. 17, 2018, pet. denied) (mem. op.).

Chi Hua Lee v. Linh Hoang Lee, No. 02-18-00006-CV, 2019 WL 3024478, at *1, *9–12 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth July 11, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

Ex parte City of El Paso, 563 S.W.3d 517, 519 (Tex. App.—Austin 2018, pet. denied).

Lucas v. Ryan, No. 02-18-00053-CV, 2019 WL 2635561, at *18 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth June 27, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

See infra Figure 8.

Glasshoff v. Vaughn, No. 10-17-00135-CV, 2018 WL 6543909, at *1 (Tex. App.—Waco Dec. 12, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.).

In re Troy S. Poe Tr., No. 08-18-00074-CV, 2019 WL 4058593, at *1 (Tex. App.—El Paso Aug. 28, 2019, no pet.).

Malone v. PLH Grp., Inc., 570 S.W.3d 292, 294 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2018, no pet.).

The discussion here excludes cases in which summary judgment motions were denied, except when the denial of a summary judgment motion was incidental to the granting of a competing summary judgment motion. E.g., Prater v. Festival of Lights of Corsicana, Inc., No. 07-17-00270-CV, 2018 WL 6729847, at *3 (Tex. App.—Amarillo Dec. 21, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.); see also Mann Frankfort Stein & Lipp Advisors, Inc. v. Fielding, 289 S.W.3d 844, 848 (Tex. 2009) (“When both sides move for summary judgment and the trial court grants one motion and denies the other, we review the summary judgment evidence presented by both sides and determine all questions presented.”). Appeals from the two orders denying summary judgment motions based on immunity grounds are addressed in Section IV.G. Appeals also may be taken from orders denying summary judgment motions based on First Amendment grounds in media cases, but during the period studied, no such orders were appealed.

See infra Figure 3.

See infra Figure 9. Only the courts that decided at least twenty appeals from summary judgments are listed separately in Figure 9. However, the statewide average is based on appeals from all fourteen courts of appeals.

Hittner & Liberato, supra note 51, at 98–100; see also Tex. R. Civ. P. 166a(b); D. Hous., Inc. v. Love, 92 S.W.3d 450, 454 (Tex. 2002).

Hittner & Liberato, supra note 51, at 96; see also Tex. R. Civ. P. 166a(b); Love, 92 S.W.3d at 454.

Tex. R. Civ. P. 166a(i).

See Tex. R. Civ. P. 166a(a).

Woodside v. Woodside, 154 S.W.3d 688, 691 (Tex. App.—El Paso 2004, no pet.); Yarbrough’s Dirt Pit, Inc. v. Turner, 65 S.W.3d 210, 216 (Tex. App.—Beaumont 2001, no pet.).

E.g., Wilson v. Nw. Tex. Healthcare Sys., Inc., 576 S.W.3d 844, 847 (Tex. App.—Amarillo 2019, no pet.).

E.g., Ochoa-Bunsow v. Soto, 587 S.W.3d 431, 453 (Tex. App.—El Paso 2019, pet. denied).

E.g., Tawil v. Cook Children’s Healthcare Sys., 582 S.W.3d 669, 674 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth 2019, no pet.).

E.g., Kiely v. Tex. Farm Bureau Cas. Ins., No. 06-19-00012-CV, 2019 WL 3269326, at *1 (Tex. App.—Texarkana July 22, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

E.g., Johnson v. Carlin, No. 14-16-00126-CV, 2018 WL 4925099, at *1 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] Oct. 11, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.); Tex. Windstorm Ins. v. Dickinson Indep. Sch. Dist., 561 S.W.3d 263, 266 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2018, pet. filed).

E.g., Katim Endeavors, Inc. v. Lockheart Chapel, Inc., No. 02-18-00358-CV, 2019 WL 4122607, at *1 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth Aug. 29, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.); Sitterle Homes – Austin, LLC v. Amin-Patel Invs., LLC, No. 03-18-00684-CV, 2019 WL 2847440, at *1, *3 (Tex. App.—Austin July 3, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

See infra Figure 10. During the period studied, summary judgments granted for personal injury plaintiffs, employees in employment cases, and insureds in insurance cases were not appealed in sufficient numbers to support a reliable reversal rate.

See infra Figure 11; see also, e.g., In re Ignacio G. & Myra A. Gonzales Revocable Living Tr., 580 S.W.3d 322, 324 (Tex. App.—Texarkana 2019, pet. denied) (holding issue of fact as to whether parents intended their adopted child to be a trust beneficiary precluded summary judgment on declaratory judgment action); Reyes v. De Alba, No. 13-16-00620-CV, 2018 WL 5289541, at *1, *3 (Tex. App.—Corpus Christi–Edinburg Oct. 25, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.) (holding issue of fact as to whether possession was exclusive and hostile precluded summary judgment on adverse possession claim).

See infra Figure 11; see also, e.g., Hernandez v. Kroger Tex., L.P., No. 01-18-00562-CV, 2019 WL 3949458, at *1, *8 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] Aug. 22, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.) (holding issue of fact on whether frequency of water falling to the floor and defendant’s knowledge of the common event precluded no-evidence summary judgment on premises liability claim).

Brantner v. Robinson, No. 10-17-00335-CV, 2019 WL 3822306, at *1, *4 (Tex. App.—Waco Aug. 14, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

StarNet Ins. v. RiceTec, Inc., 586 S.W.3d 434, 437, 450–51 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2019, pet. filed).

See infra Figure 11.

ASI Aviation, LLC v. Arnold & Itkin, LLP, Nos. 13-16-00612-CV & 13-17-00122-CV, 2018 WL 6217699, at *1, *3 (Tex. App.—Corpus Christi–Edinburg Nov. 29, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.).

E.g., Gober v. Bulkley Props., LLC, 567 S.W.3d 421, 425 (Tex. App.—Texarkana 2018, no pet.).

Liberato & Rutter, supra note 5, at 998.

E.g., Perez v. Greater Hous. Transp. Co., No. 01-17-00689-CV, 2019 WL 3819517, at *1, *3 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] Aug. 15, 2019, pet. filed) (mem. op.).

E.g., Spencer & Assocs., P.C. v. Harper, No. 01-18-00314-CV, 2019 WL 3558996, at *1, *11 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] Aug. 6, 2019, no pet.); Farias v. Juarez, No. 04-17-00789-CV, 2018 WL 6331137, at *1, *2–3 (Tex. App.—San Antonio Dec. 5, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.).

See infra Figure 12.

E.g., Propel Fin. Servs., LLC v. Conquer Land Utils., LLC, 579 S.W.3d 485, 488–89 (Tex. App.—Corpus Christi–Edinburg 2019, pet. filed); Pyote Well Serv., LLC v. Hudson Specialty Ins., No. 11-17-00147-CV, 2018 WL 4925721, at *1 (Tex. App.—Eastland Oct. 11, 2018, pet. dism’d) (mem. op.).

E.g., Eco Gen. Contractors LLC v. Goodale, No. 02-18-00146-CV, 2019 WL 1179409, at *1, *2–4 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth Mar. 14, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op); Worldwide Autotainment, Inc. v. Galloway, No. 14-17-00761-CV, 2019 WL 386056, at *1–2, *4 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] Jan. 31, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

This was true in both 2002 and 2011. Liberato & Rutter, supra note 4, at 449; Liberato & Rutter, supra note 5, at 1012. Appeals from post-answer default judgments are not analyzed here because, during the period studied, these orders were not appealed in sufficient numbers to provide a reliable sample.

E.g., Interest of T.F., No. 02-18-00299-CV, 2019 WL 2041790, at *1, *2–3 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth May 9, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.); McAlister v. Grabs, No. 11-17-00148-CV, 2019 WL 1428623, at *1 (Tex. App.—Eastland Mar. 29, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

Tex. R. Civ. P. 120 & 124; see also Hilburn v. Jennings, 698 S.W.2d 99, 100 (Tex. 1985).

Reversals in bill of review proceedings are not addressed here. An order granting a bill of review is interlocutory because it sets aside the prior judgment without disposing of the case on the merits. Kiefer v. Touris, 197 S.W.3d 300, 302 (Tex. 2006) (citing Tesoro Petrol. v. Smith, 796 S.W.2d 705 (Tex. 1990)). An appeal may be brought from a judgment for the bill of review defendant, but during the period studied, these judgments were not appealed in sufficient numbers to support a reliable analysis.

Liberato & Rutter, supra note 4, at 449; Liberato & Rutter, supra note 5, at 1012–13. For cases demonstrating appellate court reversals of a trial court’s decision to grant a default judgment and deny a motion for new trial, see Latter & Blum of Tex., LLC v. Murphy, No. 02-17-00463-CV, 2019 WL 3755765, at *1 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth Aug. 8, 2019, pet. filed) (mem. op.); Gattenby v. TIB-The Indep. Bankersbank, No. 05-18-00168-CV, 2019 WL 457600, at *1 (Tex. App.—Dallas Feb. 6, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.).

Liberato & Rutter, supra note 4, at 449–50; Liberato & Rutter, supra note 5, at 1013. For cases demonstrating appellate court reversals where a trial court granted default judgment and the defendant filed a notice of restricted appeal, see Daigrepont v. Preuss, No. 05-18-01271-CV, 2019 WL 2150916, at *1, *4 (Tex. App.—Dallas May 17, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op.); Goss v. Sillmon, 570 S.W.3d 319, 322–23 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2018, no pet.).

See Tex. R. Civ. P. 329b(a) (providing that a motion for new trial “shall be filed prior to or within thirty days”); Tex. R. App. P. 26.1(c) (providing that a restricted appeal must be perfected within six months).

Craddock v. Sunshine Bus Lines, Inc., 133 S.W.2d 124 (Tex. 1939).

Carpenter v. Cimarron Hydrocarbons Corp., 98 S.W.3d 682, 685 (Tex. 2002) (discussing Craddock); see also Craddock, 133 S.W.2d at 126.

Dir., State Emps. Workers’ Comp. Div. v. Evans, 889 S.W.2d 266, 268 (Tex. 1994).

Craddock, 133 S.W.2d at 126.

See, e.g., Fid. & Guar. Ins. v. Drewery Constr. Co., 186 S.W.3d 571, 573–74 (Tex. 2006); Norman Commc’ns v. Tex. Eastman Co., 955 S.W.2d 269, 270 (Tex. 1997).

Wachovia Bank of Del. v. Gilliam, 215 S.W.3d 848, 850 (Tex. 2007) (per curiam).