I. Introduction

Calling social dominance by more palatable names, pretending that it is only a feature of other people’s societies, assuming that it is due only to the actions of a “misguided” few, and presuming that it is merely a dying legacy of the past not only are exercises in self-delusion, but also contribute to the tenacity of group dominance by obfuscating its very existence, and thereby making it that much more difficult to change.

We judge it as considerably more harmful to the cause of equality and the fulfillment of democratic ideals to pay too little than too much attention to the dynamics of group dominance.[1]

Imagine that you are a black employee who is vying for a promotion.[2] You have worked hard trying to rise through the ranks. You have assiduously applied for more attractive jobs, but you have been out of luck for a promotion because those jobs were at other facilities, and the employer has a policy of filling vacancies from within the same facility where possible. But now, a position has opened up in your facility, and it needs to be filled quickly. You think it is finally your turn: you are the only person on the candidate list who is already working at the facility, and you are clearly qualified. If everything goes by the book, you have finally earned yourself a promotion. You are also the only black applicant for the job.

But you don’t get the job. Instead, you learn, a white male got the job. What’s more, the person who got the job was not on the initial candidate list. He was not even qualified, and thus not eligible, for the job based on the original job description. Yet, you learn that, after finding out that you would have gotten the job under existing procedures, the hiring manager ordered the job description to be rewritten. Magically, the other candidate is now the only person remaining on the new eligibility list and will be hired. You are frustrated, upset. You can’t help but think that your race was the reason that you did not get the promotion. You know Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits race discrimination in employment decisions. Surely, you think, if Title VII was written to protect anyone, it would be you. Fool me once: you are wrong. The district court judge agrees with you that you were more qualified. However, the court tells you that it was not your race that caused you not to get the promotion; it was that the manager engaged in favoritism for his “fishing buddy”—favoritism ostensibly unconnected from any racial motivation. That is a decision that the employer can legally make because favoritism unconnected to race is not illegal. So, you lose your case. You are confused. At trial, the manager had steadfastly denied any favoritism, so you think he should be held to his testimony under oath. But the district court didn’t believe those denials and concluded that favoritism is the better explanation for what happened. You hope that the appeals court will correct what seems like a clear error. Your hope is misplaced. While the court tells you that it is troubled and might have reached a different conclusion on a clean slate, it also says that it is bound by what it sees as acceptable judgment calls by the district court in interpreting the evidence. “Title VII does not have a limitless remedial reach,” the court says, and you are not within its existing reach.[3]

Now imagine that you are a black employee of an employer in financial distress, hoping not to get laid off.[4] You are somewhat hopeful. You are the only black employee in an administrative position, and your employer has committed itself to racial equity, inclusion, and diversity through an affirmative action plan that aims to achieve and protect an equitable racial composition of its workforce. But the financial situation is bad. The employer must lay off numerous people in your job category. You are initially one of them, but like all of the laid-off employees, you get a hearing to contest your layoff. After further review, the employer decides that your layoff would improperly set back its goals of racial equality in the workforce and decides to retain you after all. A white employee, who was in some respects senior to you but was laid off, sues, claiming that the decision to retain you but not her was illegal race discrimination under Title VII. Surely, you think, it must be possible for an employer to voluntarily try to retain its only black administrative employee in an effort to have a more racially equitable workforce. Fool me twice: you are wrong again. The court decides that retaining you is not a decision that your employer can legally make under Title VII. The employer could only do so if it had discriminated against black employees in the past, and there was not enough evidence of that. For the court, because there are few blacks in the local labor force, it really wouldn’t be significant for the employer to have no black employees at all. What’s more, retaining you to protect the employer’s affirmative action progress was illegal because it “unnecessarily trammel[ed]” the interests of the white employee, who the court viewed as the one who was really entitled to your position.[5]

Imagining yourself as the worker in the first scenario above puts you into the shoes of one of the most common types of litigants in the American civil justice system. Employment discrimination cases are consistently among the most frequently litigated types of civil cases in the federal courts.[6] By imagining your frustration about not receiving any relief, you also share in the feeling most commonly experienced by plaintiffs in these cases. Employment discrimination cases are notoriously difficult to win for plaintiffs.[7] Employment discrimination plaintiffs fare more poorly than other civil plaintiffs in the district courts,[8] and even if they succeed at the trial court level, they are extremely likely to have their victories overturned on appeal.[9] This pattern appears to have been in place for decades now.[10] Claims of race discrimination are perhaps the most frequently litigated type of employment discrimination case,[11] and there are some indications that race discrimination plaintiffs fare particularly poorly in the courts.[12] Racial minorities, in particular black plaintiffs, are the prototypical plaintiff in such cases. Black plaintiffs bring most employment discrimination cases claiming race discrimination.[13] Thus, the apparent antiplaintiff bias of federal judges in employment discrimination cases[14] disproportionately affects black plaintiffs, who lose most of their cases.[15] This is so even though a wide variety of data shows that racial inequality and racial discrimination against workers of color continue to pervade the American economy.[16] In the face of such continued discrimination, one might think that employment discrimination law should be equally, perhaps more, hospitable to claims by workers of color compared to other kinds of civil plaintiffs, not less. Yet, it is decidedly not.

The shape of employment discrimination doctrine under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the federal statute governing race discrimination in employment, significantly contributes to this lack of success by discrimination claimants. Scholars have criticized the doctrine as a complicated “morass”[17] that is in significant part the outcome of restrictive judicial interpretation of broad statutory language (especially since the 1980s), notwithstanding intermittent legislative intervention meant to broaden workers’ antidiscrimination protections.[18] This restrictive interpretation has created a doctrine that in many of its specifics, including in the race discrimination context, discredits discrimination claims of plaintiffs, who are predominantly workers of color.[19]

This is deeply troubling. After all, the Supreme Court has repeatedly reminded us that one of the main goals of Title VII was to create lasting improvements in the working conditions of racial minorities, in particular black Americans, and to ensure equal opportunities for minority workers to succeed in the workplace.[20] In interpreting and applying Title VII race discrimination law, the federal judiciary (including the Supreme Court itself) has not delivered on these goals for decades now. The first vignette above, taken from a real case, is illustrative of the resulting “fool me once” problem for racial minority plaintiffs: despite being the primary intended beneficiaries of Title VII’s prohibition of race discrimination, they have terrible chances of success even when they have strong evidence of such discrimination.[21]

Given the crucial importance of employment to most people’s livelihoods, especially for racial minorities who already disproportionately suffer from social and economic stratification, it is important to uncover the reasons underlying this longstanding disconnect between asserted statutory goals and interpretive practice so that effective countermeasures can be developed. Yet, comparatively few scholarly analyses, particularly outside of the implicit bias literature,[22] have tried to do so by combining traditional doctrinal and theoretical analyses with systematic empirical insights from social science.[23]

The first major goal of this Article is to offer an analytical framework that takes on this task in a novel way and explains the federal judiciary’s cramped interpretation of Title VII race discrimination law based on conclusions from social psychology. This framework combines findings from Social Dominance Theory (SDT)—a social-psychological theory with a considerable footprint in social science journals but that has yet to significantly enter legal scholarship[24]—with insights from Critical Race Theory (CRT) and conceptualizes the interpretation of race discrimination law as a mechanism through which racial hierarchy is regulated and, in the main, (re-)produced. SDT researchers have uncovered robust evidence that basic human psychological preferences for society to be organized as a group-based (including racial) hierarchy can influence different groups of people to think and behave in ways that help to create and maintain such hierarchy.[25] This Article argues that there are good empirical reasons to think that federal judges as a group (with individual variation to be sure) have comparatively strong such preferences, and that they will act in accordance with those preferences when interpreting hierarchy-relevant laws such as Title VII’s race discrimination provisions. These preferences influence, among other things, people’s baseline assumptions and perceptions of the prevalence of discrimination against different groups, their views on the desirability of antidiscrimination intervention, as well as the ideologies people use to explain the world around them. This Article analyzes Title VII race discrimination doctrine with reference to these psychological processes and shows how they explain the doctrine’s suspicion towards claims of discrimination by workers of color, its many rules that discredit their allegations, and why it rejects the vast majority of their claims as a result.[26] Uncovering the interpretation of employment discrimination law as a process at least partially driven by the judiciary’s preferences for group-based social hierarchy, in turn, has important implications for potential reform, including illustrating the likely benefits of increasing judicial diversity of various kinds.[27]

The second major goal of this Article is to show that its analytical framework not only helps us better understand the ongoing judicial interpretation of employment discrimination law, but also illustrates that popular descriptions and conceptualizations of the overall logic of Title VII jurisprudence are inaccurate and potentially unhelpful. Taking a hierarchy-centered view of Title VII doctrine counsels against accepting what seems to be a relatively broad consensus that (1) Title VII in general, and its race discrimination provisions in particular, are “symmetrical” (i.e., they protect all groups covered by the law in the same general fashion[28]); and (2) to the extent that the doctrine is asymmetrical (i.e., provides certain protections to some but not other groups), it is asymmetrical in favor of racial minorities because it allows for affirmative action.[29] This Article argues that, instead, Title VII race discrimination jurisprudence, its affirmative action doctrine included, should be understood as being fundamentally asymmetrical to the disadvantage of workers of color while protecting the interests of white workers to a greater extent.[30]

This is because, consistent with what this Article’s analytical framework predicts, the federal judiciary has interpreted Title VII in ways that make it comparatively easy to prevail for litigants whose interest is to preserve existing racial hierarchy in the workplace (most employers and white workers) and comparatively difficult for litigants whose interest is to reduce existing hierarchy (employers who pursue affirmative action and workers of color). As a result, Title VII race discrimination law is neither always hostile to plaintiffs nor always friendly to employers. Rather, it is hostile to plaintiffs in “traditional” race discrimination cases[31] like the first vignette above, which prototypically challenge racial hierarchy because they are predominantly brought by workers of color.[32] By contrast, it provides greater comparative protection to plaintiffs in affirmative action cases (prototypically white workers) in which plaintiffs aim to prevent interference with existing hierarchy, as shown in the second vignette above.[33] Similarly, employers are treated deferentially when defending “traditional” cases,[34] but with greater hostility when defending affirmative action programs.[35] One common source for all of these asymmetries is a “baseline error”—an often unspoken assumption, counter to the weight of the evidence but consistent with Social Dominance Theory, that discrimination against workers of color is not sufficiently frequent to warrant particular attention, and that discrimination against white workers warrants just as much (if not more) judicial concern.[36] In all cases, however, workers of color receive the short end of the stick because the doctrine consistently undervalues their interests. Thus, such workers disproportionately miss out on employment opportunities, and racial hierarchy in the workplace persists.

Given the Supreme Court’s repeated command that one of the main purposes of Title VII is the elimination of racial hierarchy in the workplace,[37] and the fact that Title VII grew out of the Civil Rights Movement’s efforts to end the subordination of workers of color, this is highly problematic. Research findings from SDT and the framework proposed in this Article help us explain why we should nevertheless not be surprised to see the existing doctrinal landscape. They also help us better evaluate potential unintended negative consequences of reform proposals that proceed from a view of Title VII doctrine as symmetrical or, if anything, asymmetrical in favor of workers of color.[38]

Overall, then, there are several gaps between Supreme Court rhetoric about what Title VII is meant to achieve and the actual interpretive practice of both the Supreme Court itself and the lower courts. These gaps manifest themselves in doctrinal asymmetries that consistently under-protect the employment opportunities of workers of color and can be uncovered by a close interrogation of doctrinal rules that apply to different types of cases.[39] It is important to uncover these asymmetries and their social psychological origins so that we can begin to develop countermeasures that help us move closer to the stated goals of federal employment race discrimination law.[40] This Article speaks to all of these steps.

Part II provides an overview of this Article’s main analytical framework. It begins in Section II.A with an overview of Social Dominance Theory and lays out SDT’s claim that human societies develop as, and predictably remain, group-based social hierarchies. These hierarchies are aided in their stability by a complex interplay between individual psychology, individual and institutional behavior, and social and cultural ideologies. The law can be understood to play a critical role in this process. I propose two analytical heuristics that place the interpretation of antidiscrimination law by the courts into the SDT framework. I call these heuristics asymmetrical narrowing and proof asymmetry. I also discuss important contributions that SDT can make to a more comprehensive understanding of employment discrimination law. Section II.B gives a brief overview of the concepts of “framework critique” and “baseline error” that scholars in Critical Race Theory have developed, and which integrate productively with SDT.

Part III applies the framework of Part II in analyzing Title VII doctrine and uncovering its racial asymmetries. In particular, I focus on disparate treatment[41] doctrine regulating race discrimination claims.[42] I first analyze the doctrine that applies to the claims prototypically brought by racial minorities as plaintiffs, i.e., cases like the first vignette above. In particular, I focus on the burden-shifting regime established by McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green[43] and, using the framework from Part II, show how its current doctrinal logic is fundamentally asymmetrical to the detriment of workers of color. I then compare such “traditional” disparate treatment cases to Title VII affirmative action doctrine, i.e., the doctrine that applies to cases like the second vignette above. This doctrine is based on a modification of the McDonnell Douglas scheme, but an analysis of its rules shows how Title VII operates much more favorably to plaintiffs when they are prototypically white claimants challenging interference with existing hierarchy. Both areas combine to preserve existing racial hierarchy in the American workplace. The framework developed in Part II provides a powerful aid in explaining why this is so.

Finally, Part IV begins a conversation about the implications of my analysis for potential solutions to the problematic state of employment discrimination law. I discuss some of the proposals for doctrinal reform that scholars have already offered and argue that they risk unintended consequences that may further solidify aspects of existing racial hierarchy. Their implementation could also undermine support, and a coherent ideological basis, for more effective remedies—most prominently broader affirmative action programs. Accordingly, Part IV takes a first cut at offering some alternative suggestions for reform. Some could be implemented more short term, such as modifying previous doctrinal choices. Others recognize that any lasting progress towards reducing the negative effects of racial hierarchy, and the law’s complicity in it, will have to include more structural changes. Such changes could include, most prominently, broadening the pipeline into the federal judiciary in a hierarchy-conscious manner.

II. A New Conceptual Framework

A. An Overview of Social Dominance Theory[44]

1. Basic Conceptual Structure.

Social Dominance Theory starts from the observation that, historically, all human societies producing economic surplus have organized as systems of group-based hierarchy.[45] While the specific form and ideological foundation may differ between societies and over time, the fact that human societies are structured as group-based hierarchies in which one or more social groups are dominant, and one or more social groups are subordinated, is a general feature of societies throughout history.[46]

According to SDT, this group-based hierarchical structure is based on three different stratification systems: (a) an age system in which adults have disproportionate social power over children; (b) a gender system in which men have disproportionate social power over women; and (c) an “arbitrary-set” system which implements social hierarchy along any number of socially constructed group categories that may be salient in a given society’s context, such as social class, caste, race, and others.[47] In the United States, “for most of U.S. history, race . . . has been and remains the primary basis of social stratification,”[48] and is also the primary focus of this Article. Arbitrary sets are typically associated with the most extreme forms of violence against subordinated groups and are more flexible in how they manifest themselves and change over time.[49]

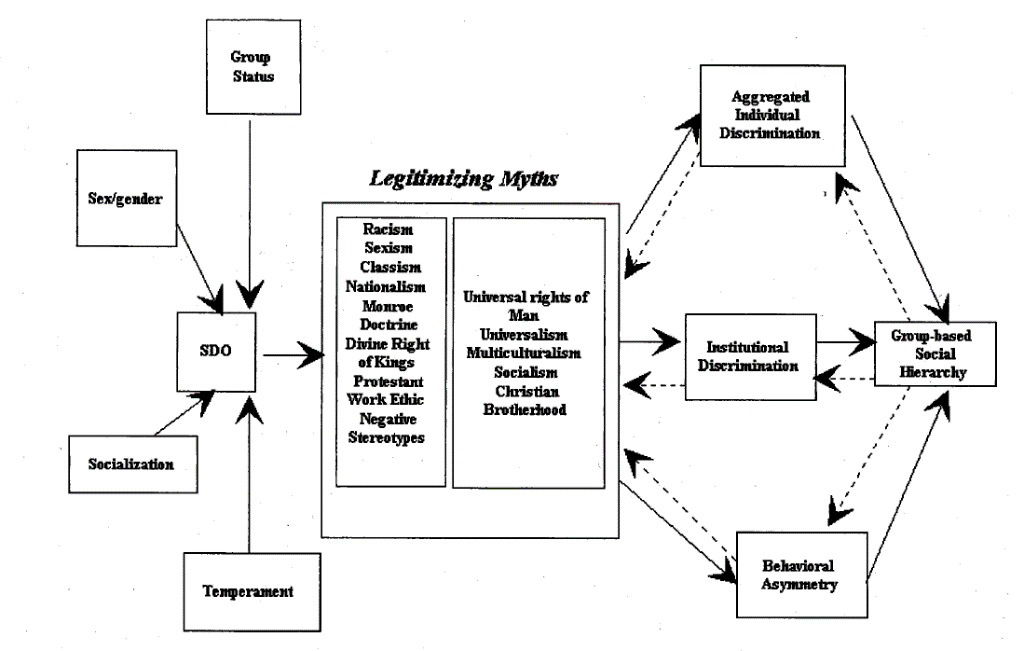

SDT sees societies as dynamic systems in which group-based hierarchy is the net effect of behavior and decision-making at various societal levels, including aggregated individual discrimination, aggregated institutional discrimination, and behavioral asymmetry among groups at different levels of the hierarchy.[50] Behavioral asymmetry refers to group differences in behavior between dominant and subordinated groups as a result of their fundamentally different social circumstances, such that dominant groups “behave in ways that are more beneficial to themselves” compared to subordinate groups.[51] These processes are mediated by legitimizing ideologies or “myths,” i.e., “attitudes, values, beliefs, stereotypes, and ideologies that provide moral and intellectual justification for the social practices that distribute social value within the social system.”[52]

People’s behavior within any given society is partially driven by individual differences in people’s support and preference for group inequality and for social systems to be structured as group-based hierarchies. This individual difference is captured by a construct called Social Dominance Orientation (SDO).[53] Although SDO is an important analytical concept within the theory, SDT does not explain societal inequality only based on individual differences[54] or considers SDO as a “pathological” condition that permanently divides “good” from “bad” people.[55] Rather, SDO is seen as an attribute “thought to reflect normal human variation and to be influenced by a combination of socialization experiences, contextually sensitive material and symbolic interests (e.g., high social status), and dispositional differences in factors such as aggression and lack of empathy.”[56] In other words, SDO is a complex and interactive variable that is sensitive to context and acts as “both an effect and a cause of intergroup attitudes and behaviors.”[57] Still, SDO has been found to be a “relatively stable cause of prejudice against outgroups and legitimizing ideologies helping to justify opposition to social policies beneficial to subordinate groups.”[58] Moreover, SDT has made a number of robust findings regarding the general distribution of SDO among different groups in society. Relevant to this Article, SDT has consistently found that members of dominant social groups, particularly dominant racial groups (whites in the United States) and men, on average have significantly higher levels of SDO than subordinate racial groups and women.[59] Thus, on the whole, members of such dominant groups will be more supportive of group-based hierarchy than women and racial minorities. As discussed below, this has significant implications in analyzing the federal judiciary and its decision-making in hierarchy-relevant contexts such as employment discrimination.

SDT is fundamentally concerned with the dynamic interaction between individual differences, social ideologies, discrimination at the individual and institutional level, and behavioral asymmetries between dominant and subordinate groups, and how the interaction of these factors creates, influences, and stabilizes group-based hierarchy.[60] In this dynamic model, the development and maintenance of group-based hierarchy are not seen as stemming from a single root cause, but rather as the result of a system in which individual parts are both a cause and effect of other parts, mutually influencing and reinforcing one another.[61]

Finally, in the SDT framework people’s behavior, societal roles, legitimizing myths, and social policies can take on two forms, depending on whether they manifest support for the maintenance or enhancement of group-based hierarchy (“hierarchy-enhancing” or “HE”) or whether they manifest support for the reduction or elimination of this hierarchy (“hierarchy-attenuating” or “HA”). The level of hierarchy in a society depends on the net balance of hierarchy-enhancing and hierarchy-attenuating forces (see Figure 1).[62]

Within this general conceptual structure, SDT has developed more specific claims which are relevant to the arguments in this Article.

2. A Closer Look at Legitimizing Ideologies.

Legitimizing ideologies or “myths” play an important role in SDT because they operationalize the idea that power and hierarchy are more effectively maintained (especially over the long-run) not with brute force, but through consensual ideology.[63] Legitimizing myths “consist of attitudes, values, beliefs, stereotypes, and ideologies that provide moral and intellectual justification for the social practices that distribute social value within the social system.”[64] A legitimizing myth can be hierarchy-enhancing when it “enhance[s] social hierarchy by justifying it or the practices that sustain it,” or hierarchy-attenuating, when it “reduce[s] social hierarchy by delegitimizing inequality or the practices that sustain it, or by suggesting values that contradict hierarchy (e.g., inclusiveness).”[65]

Legitimizing myths “mediate the relationship” between people’s individual preference for group-based hierarchy (i.e., SDO levels) and support for social policies. That is, the higher a person’s SDO level, the more likely that person is to support a HE social policy, and this relationship is explained by the person’s support for the HE legitimizing myth(s) that is mobilized to justify this policy. Similarly, the lower a person’s SDO level, the more likely that person is to support a HA social policy, and this relationship is explained by the person’s support for HA legitimizing myth(s) that justify the policy[66] (see Figure 2).[67]

Further, given that the content of ideologies is often indeterminate to some extent, the type of rationale underlying a particular ideology could be either hierarchy-enhancing or hierarchy-attenuating. SDO levels should correlate positively with HE rationales and negatively with HA rationales—even for rationales ostensibly describing the same ideology.[68] What is important about legitimizing myths is not their “objective” truth, but rather the “degree to which people believe the statement to be true, and the role that this belief plays in providing moral and intellectual support for [group, e.g.] racial domination.”[69] SDT argues that the relationship between SDO and legitimizing myths differs between social groups and that “the social attitudes and policy preferences of dominants are more strongly motivated by the desire to establish and maintain social hierarchy than those of subordinates are.”[70] In other words, on the whole, members of dominant groups, such as whites and men in the United States, are more likely to subscribe to ideologies that provide support for social practices that help perpetuate their social dominance, and to do so more strongly.

3. Sorting People into the Hierarchy.

The dynamic processes that lead to systems of group-based hierarchy also include the sorting of different types of people into different social roles.[71] For example, through a process of self-selection, hierarchy-enhancing roles or roles in HE institutions—which include profit-maximizing institutions and corporations[72] and the police[73]—are more likely to be filled by people expressing greater support for group-based hierarchy (i.e., those high in SDO). The opposite is true for HA roles and institutions[74]—which include civil rights groups, welfare organizations, or public defender’s offices.[75] SDT also argues that social institutions will in general be organized such that power and authority will disproportionately be wielded by dominant group members. That is, according to the so-called increasing disproportionality hypothesis, “the more political authority [is] exercised by a given political position, the greater the probability that this position will be occupied by a member of the dominant group.”[76]

Importantly for purposes of this Article, SDT researchers have uncovered evidence that processes of institutional socialization can affect people’s views regarding social dominance and hierarchy.[77] There is even some evidence (though not from the United States) that relates such processes to lawyers and the study of law. In particular, Guimond and colleagues found that (1) law students in France had significantly higher levels of SDO than psychology students in general; and (2) there was evidence of a socialization process resulting in upper-level (third or fourth year) law students to have higher SDO levels than first-year law students, while upper-level psychology students had lower SDO levels than first-year psychology students.[78] In other words, there was evidence for both self-selection and institutional socialization, so that exposure to a HE environment in law school increased law students’ preferences for group-based hierarchy, which were comparatively high to begin with.[79] Further, the authors found experimental evidence suggesting that being assigned or found qualified for a position of authority and high status might itself increase SDO, which in turn is related to higher prejudice towards outgroups. For example, in one of Guimond’s experiments, study participants, assigned at random to receive feedback that they “have the profile of a person who is able to lead and to hold position of high responsibility,” showed significantly higher levels of SDO than participants told that they had average such ability, as well as significantly higher antiblack prejudice.[80] In another experiment, people, assigned at random (and told that they had been assigned at random) to a position of director in a company, showed higher levels of SDO than those assigned at random to a position of secretary, as well as higher bias against North Africans.[81] Thus, the authors found the evidence “consistent with the hypothesis that being promoted to a dominant social position has a definite impact on SDO.”[82] Still, the authors also noted that “this is not to suggest that leadership as such, or any position of power in itself will produce an increase in prejudice,” but, rather, that “it is only socialization in a position in an [HE] environment that is expected to increase [HE] legitimizing myths (e.g., racism, sexism, conservatism).”[83]

4. SDT, the Law, and Judicial Interpretation.

While the law’s general position within the SDT framework has not been theorized extensively by social psychologists, the interpretation and application of the law can be understood as a critical component that contributes to the existence and stability of systems of group-based hierarchy.[84] As SDT scholars have noted, in societies that have “democratic and egalitarian pretensions,” but, nevertheless, are characterized by clear group-based hierarchy, such as the United States, the law will be one of the major mechanisms that gives this hierarchy “plausible deniability, or the ability to practice discrimination, while at the same time denying that any discrimination is actually taking place.”[85] I argue that within the SDT framework, laws and legal doctrines occupy a similar position to that of “social policy” in Figure 2, since they also implement rules regarding the distribution of resources and boundaries of appropriate behavior based on ideological justifications. In other words, taking Figures 1 and 2 together, I argue that the law mediates the relationship between personality and ideology on the one hand, and individual and institutional behavior, which in turn structures societal outcomes, on the other.

Thus, given the historical stability of group-based hierarchies,[86] on balance and over time the law should function to preserve group-based hierarchy. This is not to say that the law will, without fail and in all cases, be structured in a way that supports group-based hierarchy. As with other factors in the SDT framework, the law can also be either hierarchy-enhancing or hierarchy-attenuating.[87] In circumstances in which those with lower SDO can mobilize HA forces to a greater degree than countervailing HE forces, for example, legal regimes may emerge that partially reduce group-based hierarchy.[88] However, on balance, HE legal regimes should predominate. With respect to race in the United States, as many CRT scholars have argued, the law (including employment discrimination law) has been a primary site in which racial inequality and hierarchy has been both contested but also, in the main, legitimated.[89]

I argue that the conceptual framework of SDT and its empirical findings can, and should, be applied to inform our analysis of judges’ ongoing interpretation of the law.[90] Specifically, I argue that a synthesis of the above findings suggests that the interpretation of the law by judges, particularly when it involves hierarchy-relevant issues such as employment discrimination disputes involving claims of race discrimination, will be guided by the process of asymmetrical narrowing, and the complementary sub-process of proof asymmetry.[91]

Asymmetrical narrowing means that judges should, all else being equal, interpret legal provisions in a way that takes a narrow view of substantive rights likely to be claimed by members of subordinate groups, and a comparatively broad view of rights likely to be claimed by dominant groups. This could take the form, for example, of developing a relatively “defendant-friendly” doctrine in types of cases that are most often brought by members of subordinate groups, but a relatively “plaintiff-friendly” doctrine in cases most often brought by dominants. Alternatively, this could take the form of favoring the interests of dominant groups when substantive law requires a balancing of interests between dominant and subordinate groups. Proof asymmetry is one of the primary ways in which asymmetrical narrowing will be achieved. It refers to the idea that judges will develop legal tests and regimes that make it comparatively easy for hierarchy-enhancing litigants to prove or defend their case, particularly when it supports a HE outcome, and comparatively difficult for hierarchy-attenuating litigants to prove or defend their case, particularly when they are seeking a HA outcome. Importantly, this means that the relative treatment of one and the same litigant, such as a corporate employer, should depend to a significant extent on the relationship between the employer’s litigation position and the maintenance of racial hierarchy—i.e., whether the litigation position is HE or HA.

Expectations that judges should engage in asymmetrical narrowing and proof asymmetry in hierarchy-relevant areas, such as the interpretation of race discrimination law, can be derived from various aspects of SDT’s framework.

For example, per the increasing disproportionality hypothesis, the judiciary should be composed mainly of members of dominant groups, for whom the re-creation of group hierarchy is most in their self-interest.[92] A federal judgeship is a powerful and prestigious position, and thus can be expected to be occupied mainly by members of dominant groups—particularly white males. This is, and always has been, the case in the federal judiciary.[93] While undoubtedly there are dominant group members that are opposed to group-based social hierarchy, and some will be part of the judiciary, SDT research suggests that, on the whole, their “social attitudes and policy preferences . . . are more strongly motivated by the desire to establish and maintain social hierarchy.”[94] This suggests that, as a group, federal judges will have more of an interest to preserve hierarchy than to subvert it.

More specifically, as most judges are from dominant groups,[95] have been assigned to a significant position of leadership, and, through the appointment process, have been given feedback that they are, in fact, highly qualified for it,[96] they can also be expected to have—on the whole, and with individual variation to be sure—comparatively high levels of SDO.[97] As discussed above, this should be particularly true for white male judges. These higher SDO levels should lead judges to interpret race discrimination law in hierarchy-enhancing ways. This is because higher levels of SDO are not only associated with greater general support for group-based hierarchy,[98] but researchers have also found a strong direct relationship between SDO and opposition to antidiscrimination policies,[99] including in the employment context. For example, researchers have found that people with higher SDO levels are more likely to disagree with statements like “Society should make sure that minorities get fair treatment in jobs” and “We need to take more action to help stamp out the subtle discrimination that members of certain social groups still face.”[100]

As discussed in more detail below, this relationship between SDO and opposition to antidiscrimination policy is influenced by the fact that people higher in SDO perceive less inequality to exist in society.[101] Higher levels of SDO have also been connected to perceptions that greater racial progress has been achieved since the 1960s, and that racial remediation is a zero-sum affair in which gains for minorities must involve losses for whites.[102] Higher SDO also seems to lead people to dislike black, but not white, workers claiming to have been discriminated against,[103] likely because “discrimination claims made by members of racial minority groups potentially question the legitimacy of the racial hierarchy, [and thus] perceivers relatively high in anti-egalitarian sentiment react in a particularly negative manner toward such claimants.”[104] As Part III explains, such hierarchy-enhancing views about the “facts” of discrimination underwrite significant parts of why current workplace race discrimination doctrine is so hostile to the interests of workers of color, but comparatively friendly to the interests of white workers and most employers.

Finally, SDT research suggests that motivations to maintain hierarchy should play a significant role in how judges choose ideological justifications to support their interpretation of the law.[105] Judges, especially appellate judges, support doctrinal rulings with legal principles and ideologies that are meant to give consistent guidance on how similar types of cases ought to be resolved. SDT suggests that these ideologies will tend to be hierarchy-enhancing rather than hierarchy-attenuating,[106] particularly when the hierarchy is being threatened.[107]

In the context of race discrimination law, the ideology of colorblindness, in particular, plays a significant role.[108] Research relating SDO and colorblindness suggests a complex relationship between general support for hierarchy maintenance and endorsement of colorblindness, in part because the meaning of “colorblindness” is highly indeterminate. Colorblindness could be interpreted as a distributive justice commitment to more equal (i.e., colorblind) societal outcomes, in which case it would function as a HA ideology; but it could equally be interpreted as a procedural justice commitment to formally equal treatment, irrespective of its outcomes, in which case it has the tendency to perpetuate existing hierarchical distributions of social resources and would function as a HE ideology.[109] Thus, the particular rationale underlying a commitment to colorblindness, the way in which colorblindness is framed, is important to its relationship with SDO.

What existing research suggests is that people who are higher in SDO endorse procedural understandings of colorblindness strategically to protect existing hierarchy, particularly when that racial hierarchy is under threat.[110] For example, Knowles and colleagues found that (1) white Americans with high SDO levels were more likely to construe colorblindness as a procedural justice mandate when experiencing racial intergroup threat;[111] (2) they were more likely to endorse colorblindness when feeling under threat;[112] and (3) it was a desire for procedural justice that made high-SDO whites more likely to endorse colorblindness when feeling under threat.[113] In other words, “rather than rejecting color blindness—an ideology widely accepted as a moral imperative—when the status quo is threatened, antiegalitarian White people construe it in a fashion that furthers their hierarchy-enhancing goals.”[114]

All of these findings converge towards suggesting that, overall, judges should be more motivated to maintain a hierarchical status quo—influenced by perceptions of low existing social inequality, a zero-sum view of remediation, a negative view of discrimination claimants of color, and ideologies of procedural colorblindness. This Article argues that these dynamics manifest themselves in asymmetrical narrowing and proof asymmetry. Part III will show how this process is reflected in disparate treatment race discrimination law, how this has made existing doctrine fundamentally asymmetrical to the detriment of workers of color, and how doctrinal forks along the road were taken to arrive at this outcome.

5. Important Contributions of SDT.

Before I engage in this analysis, however, I do want to state clearly that in making my arguments in this Article, my point is not that SDT concepts can provide all the answers or fully explain the incredibly complex process of judging. I don’t believe there is a single theory, social psychological or otherwise, that can do so. Nor do I believe that SDT could reliably predict the decision-making of individual judges in individual cases with all of their complexity.[115] Nevertheless, in trying to understand the complex web of reasons for how laws operate, and how they are interpreted and applied, SDT has a significant role to play.

In looking to SDT to help explain the contours and outcomes of employment discrimination law, the goal is not to displace other useful insights, but rather to “add an additional explanatory layer to [obtain] the deepest understanding of persistent inequalities among social groups.”[116] There are clear benefits that come with mobilizing SDT in this effort.

For one, there is good reason to believe that SDT is particularly well-suited to inform our analysis of how employment discrimination law is interpreted. SDT foregrounds an important motivational dimension of how people behave when relations between salient social groups are at issue: they often act to a significant extent in accordance with general human tendencies to want to establish and maintain group-based hierarchical social systems. As noted above, research in the SDT tradition has provided powerful evidence that this psychological tendency exists as such; that it motivates the behavior of dominant group members to a greater extent; and that it manifests itself in support for a wide range of ideologies and behaviors that serve to maintain group-based hierarchy, particularly when the hierarchy is threatened. The interpretation of employment discrimination law, and antidiscrimination law more broadly, revolves in significant part around whether existing group-based hierarchy, and the position of different groups within it, is appropriate. This interpretation is done mostly by dominant group members; is based on ideologies and assumptions about the extent and appropriateness of existing hierarchy; and allegations of discrimination threaten the legitimacy of such hierarchy, particularly when raised by members of disadvantaged minority groups. Thus, SDT’s findings are highly relevant and directly tailored towards helping to explain judicial behavior in this space.

Moreover, the judicial interpretation that has led to the racial asymmetry in employment discrimination law that I analyze in Part III does not involve the kind of behavior for which cognitive explanations, including implicit bias, are most persuasive. Cognitive explanations such as implicit bias are particularly applicable to situations where the decision-maker “lacks . . . motivation, time, or cognitive capacity,” is “physically or mentally fatigued,” or has to make an “inherently ambiguous” decision.[117] By contrast, the judicial decision-making that I analyze in this Article often involves considered choices about baseline assumptions that the doctrine should make regarding the continued persistence (or not) of discrimination, the relative need for antidiscrimination intervention, and the relative strength of the interests of different participants in employment discrimination cases (workers of color, employers, white workers). SDT researchers have made specific findings as to how the motivation to create and maintain group-based hierarchy influences such choices. Thus, SDT-based research is a particularly helpful tool when analyzing legal decision-making in hierarchy-relevant contexts like employment discrimination law.

Taking hierarchy-related motivational psychological processes seriously is even more important when race discrimination is at issue. As numerous scholars have illustrated, the history of race relations in the United States is one of creating, maintaining, managing, enforcing, and contesting racial hierarchy, including through law.[118] If there is an area of American law in which the findings of SDT are especially likely to have explanatory power, it should be race discrimination law. Thus, since existing approaches, such as implicit bias research, have made important findings on the basic psychological processes that influence judges in particular circumstances, but leave a significant amount of variance in the highly complex area of discrimination-related behavior unexplained;[119] and since we are often unable to directly investigate the psychological tendencies of the judiciary; looking to directly applicable social psychological findings from SDT is highly valuable in explaining the shape of legal doctrine particularly when, as I show in Part III, the doctrine aligns with predictions we can fairly make based on those findings.[120]

Consider one brief example that I believe illustrates how an SDT-informed analysis of employment discrimination law can be complementary to, and go beyond, what has already been proposed. In a 2012 article, Professor Katie Eyer provided a thorough analysis of potential reasons for the poor odds of discrimination plaintiffs, including employment discrimination plaintiffs.[121] Eyer argued that social psychology scholarship on attribution can help explain these poor odds,[122] and in particular two phenomena: the well-documented tendency of people to hesitate to attribute a bad event to discrimination if they strongly believe in meritocracy; and the tendency to believe that discrimination (as generally understood) is relatively rare, making discrimination less cognitively accessible and thus leading people to be less likely to attribute a bad event to discrimination.[123] An analysis grounded in SDT is complementary—and provides additional insights—to Professor Eyer’s helpful work. For one, such an analysis can provide greater specificity in certain contexts. As SDT research has shown, people’s willingness to believe that discrimination and hierarchy are relatively rare is not randomly distributed—rather, it varies by a person’s SDO level.[124] This finding allows us to go beyond Eyer’s analysis, which shows that judges generally should be comparatively unwilling to make discrimination attributions.[125] SDT suggests that particularly those judges who are likely to have high SDO levels, for example because they are from dominant groups, should be even more unwilling compared to judges who are likely to have lower SDO levels, for example because they are from nondominant backgrounds.

As a result, an SDT-informed analysis can more parsimoniously explain some of the findings that have been made regarding the role of a judge’s race in deciding employment discrimination cases. While the findings are not perfectly consistent, there are a number of studies that suggest that judges from racial minority backgrounds, particularly black judges, are significantly more likely to find in favor of employment discrimination plaintiffs than white judges.[126] In other words, judges in these studies were not all equally unlikely to make attributions to discrimination. Rather, those most likely to have low levels of SDO, and thus hierarchy-attenuating views, were significantly more likely to make such attributions. Thus, consistent with SDT-based predictions, these judges were more likely to act in hierarchy-attenuating ways and rule in favor of plaintiffs that challenged employment discrimination, even in the face of a hostile doctrine. This analysis is not necessarily inconsistent with that of Professor Eyer, but it helps build on that analysis and provides even greater specificity.

As I describe in Part III, SDT-infused analysis provides useful insights in helping to explain important aspects of the content and underlying logic of employment discrimination doctrine as well. Thus, it should be considered a valuable analytical tool for lawmakers, judges, academics, and advocates alike. Before moving to my SDT-informed doctrinal analysis, however, Section II.B briefly introduces the concepts of “framework critique” and “baseline errors” that I will also mobilize in evaluating existing doctrine in Part III.

B. Framework Critique and Baseline Errors

Combined with analytical tools from SDT, this Article applies a so-called “framework critique,” a concept that has played an important part in the work of Critical Race Theory scholars.[127] Such a critique recognizes that “the frameworks we use to understand and describe social facts are constructed in the context of particular political and social activities and projects,” and in the context of race and the law, frameworks of “equality” may serve to “reinforce[] racial privilege as part of a broader conservative project to limit a wide-ranging redistribution of resources along racial lines.”[128] In other words, the frameworks within which we debate questions of racial equality, and the starting points from which we measure the existence of such equality, are ideologically contingent. In many cases, existing frameworks in the law “do conservative political work in the context of particular historical periods to protect white interests.”[129]

Noah Zatz recently applied this kind of critique to Title VII in analyzing the frequent use of the often ill-defined term “special treatment” by courts and scholars when discussing discrimination cases,[130] and in the process explained the important concept of “baseline errors.” Zatz argues that an accusation that a particular employer action, or perhaps a court order, that treats employees from different racial groups non-identically involves “special treatment” (an accusation that generally tries to suggest that the treatment is itself discriminatory)[131] cannot be appropriately analyzed without first establishing the “relevant nondiscriminatory baseline.”[132] Where race discrimination has affected the status quo distribution of employment benefits, this nondiscriminatory baseline should be “the world as it would have been without” the discrimination.[133] In such situations, treating employees from different racial groups non-identically may well be remedial rather than discriminatory, i.e., “not merely nondiscriminatory, but antidiscriminatory: necessary to remedy discrimination”[134] if the non-identical treatment helps to recreate the nondiscriminatory baseline from which discrimination caused a deviation.[135]

To disregard the relevant nondiscriminatory baseline and assume instead that a discriminatory status quo, i.e., “the world created by [the] discrimination,”[136] is the nondiscriminatory baseline is to commit a “baseline error”[137] that confuses remediation with discrimination based on “decontextualization.”[138] Acting on such a baseline error, in turn, not only enables the denigration of remedial action as inappropriate “special treatment,” but also tends to normalize inequalities that stem from discrimination:

When the benefits of discrimination against others are taken as a baseline entitlement, an intervention’s remedial character becomes invisible. Instead, that equalizing intervention looks like special treatment, raw redistribution away from members of a dominant group who earned their place at the top. This dynamic simultaneously shields discrimination’s beneficiaries from acknowledgement of their windfall and derogates discrimination’s victims as undeserving when they receive relief.[139]

This Article argues that a significant portion of current Title VII disparate treatment doctrine proceeds from such a baseline error and consequently leads to asymmetrical outcomes that disfavor workers of color and entrench racial hierarchy in the workplace. This baseline error is to take prevailing—and historically persistent—racial inequalities that subordinate workers of color as normal and presume such inequalities to be the result of nondiscriminatory decisions.[140] As a result, discrimination against such workers is perceived as the exception, rather than a regular feature of employer decision-making; claims of discrimination by workers of color are viewed with suspicion, and employer assertions of nondiscriminatory reasons for employment decisions are taken as more credible than employee allegations of discrimination. At the same time, this erroneous baseline is used to justify the view that white workers should be protected from “reverse discrimination” on facially identical (and perhaps more favorable) terms as workers of color, and that doing so is merely extending the “same” protective treatment to everyone. By contrast, affirmative action programs are construed as deviations from this baseline that require extraordinary justification because they involve highly problematic “special treatment” and unearned “preferences” for minorities.[141]

I argue that the appropriate baseline would instead be to recognize that major racial inequalities persist in the American economy and that these inequalities almost uniformly disadvantage workers of color. This baseline would recognize that racial discrimination—even if conceived of by the basic test that asks whether the outcome for one and the same, say black worker, would have been different if she had been white—continues to be the reason underlying such inequalities in enough cases that it is appropriate to take claims of discrimination by minority plaintiffs at least as seriously as assertions by employers that they acted for nondiscriminatory reasons,[142] and more seriously than claims of white plaintiffs that they suffered “reverse discrimination.”[143]

Consider, for example, that notwithstanding Title VII’s now fifty-year tenure, persistent and large gaps continue to define America’s economy along racial lines. As of the late 2000s, black and Hispanic men on average earn less than three-quarters of the earnings of white men, and black and Hispanic women earn substantially less than white women.[144] Black and Hispanic unemployment has for decades consistently been significantly higher than white unemployment.[145] EEOC data shows that as late as 2015, at a national level, minority workers are strongly underrepresented compared to their share of the labor market in the job categories “Executive/Senior Level Officials & Managers,” “First/Mid Level Officials & Managers,” “Professionals,” and “Craft Workers” but strongly overrepresented in the categories of “Operatives,” “Laborers,” and “Service Workers”.[146] These labor market numbers show a clear racial hierarchy that continuous to disproportionately distribute the most attractive jobs to white Americans and the most unattractive ones to workers of color.

While there are various reasons for such disparities, race discrimination continues to be a highly significant contributor. Audit studies consistently show that racial differences in employment outcomes do not result solely from differences in individuals’ interests, credentials, or potential, but that being a member of a racial minority group (or being perceived as such) significantly and negatively affects one’s access to employment benefits.[147] Such findings have been made across different locations and levels of job selectivity, showing that racial discrimination hurts minority workers from the low-wage economy to jobs requiring college degrees.[148] In certain labor markets, a white job applicant with a criminal record for possession of cocaine can still do “just as well, if not better” than Latino and black job applicants with no criminal background.[149] Such racial disadvantage accumulates over a worker’s career, leaving employees of color more and more behind over time—particularly at higher levels of education.[150] Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of more than thirty audit studies covering a forty-year period from the mid-1970s to the mid-2010s suggested that hiring discrimination against workers of color “neither declined over time nor varied by education level or type of occupation involved.”[151] Overall, scholars have noted that across methods of investigation, “considerable scientific evidence of the persistence of workplace discrimination is evident in audit studies, grounded labor market analyses, social psychological research using experimental designs, and surveys of ordinary citizens.”[152]

Part III shows how significant aspects of current disparate treatment doctrine do not take this baseline of a racially stratified American economy into account. As a result, we see a doctrine that leads to systematic asymmetrical treatment to the detriment of workers of color and helps maintain a system of racial hierarchy in employment. Research from SDT scholars gives us persuasive explanations as to why this is so.

III. Disparate Treatment Doctrine Asymmetrically Disfavors Workers of Color and Helps Maintain Racial Hierarchy

This Part provides three examples of how Title VII disparate treatment doctrine creates asymmetries in how it treats plaintiffs of color and in doing so helps maintain racial hierarchy in the workplace. Two of these examples come from what I call “traditional” disparate treatment cases, in which plaintiffs claim that an employer intentionally took an adverse employment action against them because of their race, while the employer claims that it took the action for nonracial reasons. I focus on cases proceeding under the so-called McDonnell Douglas burden-shifting regime. The third example compares the doctrine governing such traditional cases with Title VII affirmative action doctrine and argues that this comparison illuminates another asymmetry disfavoring workers of color. Throughout, I show how the framework from Part II helps to persuasively explain why we should expect such asymmetries to develop. First, however, I provide some background on relevant disparate treatment doctrine to set the stage for the critical analysis that follows.

A. Disparate Treatment Doctrine Background

The general idea underlying Title VII’s prohibition of disparate treatment in employment decisions is relatively easily stated. When an employee brings a disparate treatment claim, the ultimate fact that she has to prove is that the employer intentionally discriminated against her in a relevant employment decision because of a protected characteristic covered by the statute, including race.[153] In other words, the general elements of a disparate treatment claim are (1) an adverse employment action; (2) discriminatory intent; and (3) causation, or a linkage between intent and employment action.[154] Various difficulties arise, however, when this inquiry is applied in individual cases because (1) it calls for an evaluation of the decision-makers’ mental states—their motive(s) or intent—which is difficult, if not impossible, to observe, and thus prove, directly;[155] (2) the employer usually controls most of the relevant evidence;[156] and (3) human behavior, and thus employment decisions, are usually motivated by many different factors, leading to questions about how important the consideration of a protected characteristic must be before an employment decision counts as illegal disparate treatment.[157] Trying to respond to these issues, disparate treatment law has developed a complicated array of legal tests and rules.

The most common way in which plaintiffs can attempt to prove unlawful disparate treatment is through one of the more formalized burden shifting mechanisms that courts have developed over time.[158] The basic dividing line in this context is between the analysis established by McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,[159] also sometimes called the “pretext” regime, and the so-called mixed motives analysis, also sometimes called the “motivating factor” regime, that was initially put forth by the Supreme Court in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins[160] and subsequently codified in modified form by the 1991 Civil Rights Act.[161]

Under McDonnell Douglas, the analysis proceeds in three steps: (1) a plaintiff must first establish a very specific type of prima facie case, which, if shown, creates a mandatory rebuttable presumption that discrimination occurred;[162] (2) the employer may rebut this showing by introducing evidence of a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for the challenged employment action; and (3) the plaintiff may then try to establish that the reason offered by the employer was not the real reason for the action, but rather a pretext for illegal discrimination.[163] A plaintiff must succeed in showing that her protected characteristic—for example, her race—was a but-for cause of the challenged employment action.[164] If plaintiffs succeed in proving a case under this regime, they are eligible for the full slate of remedies available under Title VII, including compensatory and punitive damages.[165]

Under a mixed motives analysis, a plaintiff must only establish that her race was at least one of the employer’s motivations for a particular employment decision—in other words, that it was a “motivating factor” for the decision even though there may have also been other, lawful motivations.[166] Race need not have been the but-for cause of the decision.[167] If a plaintiff makes this showing, the employer is liable for disparate treatment. But, if the employer can show that it would have made the same decision even absent the unlawful consideration of race, it can limit the plaintiff’s remedies to declaratory relief, certain injunctive relief, and attorney’s fees.[168]

The way in which these two regimes relate to each other, and to which types of cases they apply, has been disputed for as long as the regimes have existed.[169] This Article focuses its doctrinal analysis[170] on the McDonnell Douglas regime. While the continued relevancy and vitality of the regime have been questioned by some,[171] I make this choice for the following reasons. For one, “courts still rely heavily on the McDonnell Douglas framework in Title VII disparate treatment cases.”[172] The Supreme Court, too, continues to use the framework in the disparate treatment context without any suggestion that it has lost its usefulness.[173] Second, even though plaintiffs may bring claims under both frameworks,[174] there are reasons to think that a significant number of plaintiffs will choose to pursue their cases only under a McDonnell Douglas approach to avoid allowing the employer to raise the same-decision defense and limit the plaintiff’s remedies.[175] Lastly, the McDonnell Douglas framework is frequently used in reverse discrimination cases brought by white plaintiffs, and a modified version of the framework is used to evaluate challenges to affirmative action programs—both of which I analyze in more detail below. Accordingly, to provide a more coherent analysis, and recognizing that there is only so much that can be achieved in a single article, my focus will be on the McDonnell Douglas framework.

I argue that the logic and application of this burden-shifting regime creates doctrinal asymmetries that disadvantage workers of color throughout its various stages, asymmetries that can be explained when viewed through the lens of racial hierarchy and the framework established in Part II.

B. Asymmetry Examples

1. Example 1: The Prima Facie Case and “Background Circumstances.”

The first step for any plaintiff under the McDonnell Douglas regime is to establish a prima facie case of discrimination. The main purpose of this step is for the plaintiff to bring forward the type of evidence that, if left unrebutted by the employer, allows for the inference (indeed presumption) that illegal discrimination more likely than not explains the employer’s adverse action.[176] For example, in McDonnell Douglas, which involved a discriminatory failure-to-hire claim, the Court determined that a prima facie showing could be made by establishing that the plaintiff (1) “belongs to a racial minority”; (2) “applied and was qualified” for the job at issue; (3) was rejected “despite his qualifications”; and (4) “the employer continued to seek applicants” with similar qualifications.[177] The Court recognized, though, that different factual situations may call for different prima facie elements,[178] and courts have indeed adjusted the elements for different types of claims.[179] For example, in a case alleging discriminatory discharge, a court might require a plaintiff to show that she met the employer’s legitimate expectations for her job, was discharged nevertheless, and the employer sought a replacement.[180] The goal is to “eliminate[] the most common nondiscriminatory reasons for” the allegedly discriminatory employment decision.[181] After all, when such nondiscriminatory reasons are not applicable, and the employer provides no other reason, one can reasonably infer that, rather than acting in a “totally arbitrary manner,” the employer instead acted “more likely than not based on the consideration of impermissible factors.”[182]

Constant across all formulations of the McDonnell Douglas prima facie case, however, is that membership in a “protected class” is always its first prong.[183] In a superficial way, this makes sense; liability under Title VII requires an adverse employment action that was taken “because of” an employee’s race.[184] Thus, an employee must be a member of a racial group to be discriminated against “because of” this membership. However, this prong becomes more curious if one considers that all racial groups are protected from race discrimination by Title VII, including white workers, as the Supreme Court has clearly held.[185] If all racial groups are protected, every plaintiff can presumably automatically fulfill this first prong. Does the racial group membership requirement of the McDonnell Douglas prima facie case then do any substantive work in deciding whether it is reasonable to draw an inference of discrimination from a particular set of facts?

I argue that the answer depends on what one views as the relevant nondiscriminatory baseline and, relatedly, one’s view regarding the extent to which different racial groups have been, and continue to be, at risk of racial discrimination in the workplace. If all racial groups are at a substantial, or at least nontrivial, risk of race-based discrimination, then it makes sense to use racial group membership as such, together with other elements tailored to “eliminate[] the most common nondiscriminatory reasons for” a particular type of employment decision, and to conclude that an inference of discrimination is reasonable when all elements have been proved.[186] Based on such a nondiscriminatory baseline, symmetrical treatment, i.e., asking plaintiffs of all racial groups to meet the exact same legal test, would also be equal treatment. Alternatively, one may think that members of some racial groups, particularly white workers, are at a much lower, perhaps negligible, risk of being discriminated against specifically based on their race. Proceeding from this baseline, one will not be willing to assume that the fact that a worker is white makes race-based discrimination the most likely explanation for a negative employment decision against that worker, even if the most common nondiscriminatory reasons for the decision have been eliminated via the remaining prongs of the prima facie case. Instead, one will require additional evidence suggesting that an employer took the unusual step (unusual at least in the American context) to discriminate against a white worker specifically because she was white. Indeed, not requiring such additional evidence would be “special treatment” of white plaintiffs by allowing them to benefit from a mandatory presumption of discrimination that is not justified by the evidence they have presented.[187]

This is precisely the debate that has played out in the lower courts.[188] More so than in some other contexts discussed below, some courts have recognized that there is a debate to be had over what the relevant analytical baseline should be, and what the corresponding implication is for Title VII disparate treatment doctrine. The result is a circuit split between courts that favor an identical legal standard for plaintiffs from all racial groups and those that recognize that equal treatment of all racial groups requires white plaintiffs to meet a different evidentiary standard.

On the one hand, various circuits have modified the first prong of the prima facie case for white plaintiffs and have required them to meet a so-called “background circumstances” test.[189] This test requires a showing of “background circumstances [that] support the suspicion that the defendant is that unusual employer who discriminates against the majority.”[190] Some of these courts specifically recognize that not to apply a modified standard for white plaintiffs would be to commit a baseline error—to assume that discrimination against white workers is as likely as discrimination against workers of color when the realities of the American economy simply do not support this assumption.

This would, in turn, unjustifiably provide greater (i.e., asymmetrical) legal protections to white plaintiffs.[191] These courts recognize that the equal protection of workers of color and white workers requires taking into account an unequal baseline situation in the American economy: given consistent and pervasive racial inequality in employment favoring white workers,[192] it is reasonable to infer discrimination (and require the employer to state its reason for the adverse action) from the combination of the remaining prongs of the McDonnell Douglas prima facie test and the fact that a plaintiff belongs to a racial minority. It is not reasonable, without more, to make the same inference for white plaintiffs.

However, not all courts apply the background circumstances test. While courts have relied on different reasons to reject the test,[193] some circuits reject the test using reasoning that directly contradicts the above analysis. These courts insist that the first prong of McDonnell Douglas must be in all cases, including for white plaintiffs, the generic requirement of being a “member of a protected class.” For example, the Eleventh Circuit in Smith v. Lockheed-Martin Corp.[194] required only a showing that the plaintiff “is a member of a protected class (here, Caucasian).”[195] In a footnote, the court made clear that the circuit had “rejected a background circumstances requirement” and buttressed this conclusion with the statement that “[d]iscrimination is discrimination no matter what the race, color, religion, sex, or national origin of the victim.”[196]

As noted above, courts taking this approach implicitly proceed from a baseline where white workers and workers of color face similar risks of race discrimination and the inference of discrimination from the remaining prongs of the prima facie case is equally strong for workers of all racial backgrounds. I argue that this commits a fundamental baseline error that erases the starting point of continuing racial inequality in the workplace. Through such “decontextualization,”[197] this error doctrinally entrenches the “baseline entitlement” of white workers to a discriminatory status quo[198] by giving them access to a mandatory inference of discrimination based on facts and assumptions that ignore their dominant position in the racial hierarchy and their favored status in the workplace. To put the point slightly differently, to the extent that courts reject the background circumstances test (or, as some circuits have done, begin to soften[199] or question[200] it), they instantiate doctrinal asymmetry that disfavors workers of color.

Findings from Social Dominance Theory connect this doctrinal debate to people’s predispositions towards maintaining existing racial hierarchy in the American workplace. This research shows that a person’s level of support for the maintenance of group-based hierarchy, i.e., a person’s SDO level, strongly influences related views regarding how much inequality currently exists in society—and thus one’s choice of the baseline from which to evaluate claims of discrimination. For example, Kteily and colleagues recently observed that when they asked study participants to rate how much power various racial groups had in American society, people with high SDO scores thought that there was comparatively less racial hierarchy in America than did low-SDO participants.[201] This perception, in turn, made the high-SDO participants significantly less supportive of antidiscrimination policies.[202] The authors concluded that “people come to perceive systematically different levels of inequality depending on how desirable they believe it [i.e., inequality] to be,”[203] which in turn “reinforce[s] their convictions about the types of social policies they tend to favor.”[204] In other words, if people are motivated to establish and maintain hierarchy, they perceive less inequality (including racial inequality) and thus believe that less egalitarian intervention to protect the disadvantaged (e.g., racial minorities) is required.

The flipside of this is, of course, that comparatively more egalitarian intervention is required on behalf of whites, who as participants in a flat hierarchy are perceived to be at an equal risk of racial discrimination. SDT research has made empirical findings in this regard as well. For example, Eibach and Keegan found that white Americans were significantly more likely to think about racial progress in zero-sum terms (i.e., progress for some means losses for others) than racial minorities.[205] In turn, white participants with greater zero-sum thinking judged the level of progress made towards racial equality since the 1960s as the highest among all participants.[206] SDO also predicted both sentiments: higher levels of SDO correlated with perceptions of greater racial progress since the 1960s, and high-SDO participants found it much easier to come up with examples of how “minority progress had harmed Whites” than ways in which racial progress helped whites.[207] In other words, whites and individuals with high SDO appear to see the country further along in creating racial progress – progress which they view as entailing losses for them.

This view can easily translate into a belief that whites are victimized by racial progress, and that there is both less need for the law to intervene to protect minority groups and a greater need to intervene on behalf of whites. Research by Michael Norton and Samuel Sommers confirms that whites increasingly see themselves as victims of discrimination.[208] Asking their participants to rate the level of discrimination that both white and black Americans have faced in each decade from the 1950s to the 2000s, they found that white Americans believed that by the 2000s, whites on average experienced greater levels of antiwhite bias than black Americans experienced antiblack bias.[209]

These research findings are arguably reflected in court decisions that reject the background circumstances test. Judges faced with deciding whether to apply the test are making a doctrinal choice that is not predetermined. The Supreme Court has not spoken on this issue apart from noting that the elements of the prima facie case should require “evidence adequate to create an inference that an employment decision was based on an illegal discriminatory criterion.”[210] Some judges reject the background circumstances test because they think that it inappropriately heightens the burden of proof for white plaintiffs[211] and requires an adjusted approach towards claims of discrimination by whites when they suffer the same discrimination as racial minorities.[212] This is a view of the American workplace in which existing inequality and hierarchy are low, and dominant group members, such as white males, are subject to significant amounts of discrimination. This view proceeds from a baseline error and, as research on SDT shows, is characteristic of attempts to support and maintain group hierarchy. Judges accomplish such hierarchy maintenance through proof asymmetry when they reject the background circumstances test and apply a legal test that makes it comparatively easier for hierarchy-enhancing individuals—white reverse-discrimination plaintiffs—to prove their case.

This doctrinal move to implement proof asymmetry can have downstream effects that directly and negatively affect the ability of workers of color to remedy existing hierarchy in the workplace. Consider Ricci v. DeStefano.[213] In Ricci, a group of mostly white firefighters sued the City of New Haven when the City refused to certify the results of a firefighter promotional exam, which would have disproportionately excluded black firefighters from promotions, because it was worried about the design and fairness of the test and that certifying the results would expose the City to disparate impact liability.[214] The Supreme Court overturned the City’s actions as illegal race discrimination. Importantly, the majority proceeded from “this premise: The City’s actions [in refusing to certify the results] would violate the disparate-treatment prohibition of Title VII absent some valid defense.”[215] The Court cited no precedent nor much argument for this proposition. It simply asserted that because the City had taken its actions in light of the race-based disparity in test results, it had acted “because of race” and thus presumptively violated Title VII’s disparate treatment prohibition.[216]